Communisttakeove545503unit Bw.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LABOR and the SOVIET SYSTEM, by Romuald Szumski, Is a Factual Story About the Destruction of Democratic Trade Unions Under Russian Bolshevism

c NATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR A FREE EUROPE, INC. 350 Fifth Avenue, New York 1, N. Y. Telephone: BRyant 9-2100 LABOR AND THE SOVIET SYSTEM, by Romuald Szumski, is a factual story about the destruction of democratic trade unions under Russian Bolshevism. The author clearly shows that real trade unions do not exist in Russia or its satellite countries. He describes Soviet slavery and the extension of this most barbaric system of Russian imperialism into Eastern Europe. This hard-hitting account is the answer to those who think free workers have nothing to fear from the Kremlin's "dictatorship of the proletariat*1. I strongly urge you to read LABOR AND THE SOVIET SYSTEM and see the deceptive and fraudulent tactics and devices of Russian communism exposed. I ask you to join us in the relentless battle to restore and preserve freedom and peace. Please write me if you would like further details of our Committee. C, D. Jackson April, 19^1 ~; President Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis By Komuald Szumski LABOE and the Soviet System National Committee for a Free Eurbpe, Inc. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis o ONLY A WORLD BUILT ON THE IDEALS OF FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY CAN LIVE IN PEACE NATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR A FREE EUROPE, INC. 301 Empire State Building 350 Fifth Avenue, New York 1, N. Y. MEMBERS C. L. Adcock William Green Raymond Pace Alexander Joseph C. Grew Frank Altschul Charles R. Hook Laird Bell Palmer Hoyt A. -

The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness--A Soviet Spymaster Ebook

SPECIAL TASKS: THE MEMOIRS OF AN UNWANTED WITNESS--A SOVIET SPYMASTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anatoli Sudoplatov, Pavel Sudoplatov, Leona P Schecter, Jerrold L Schecter | 576 pages | 01 Jun 1995 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316821155 | English | Boston, MA, United States Lord of the spies: The 4 most impressive operations by Stalin’s chief spymaster - Russia Beyond Robert Oppenheimer and Leo Szilard, all of whom are dead and were eminent scientists. Both Dr. Bohr and Dr. Fermi won the Nobel Prize for basic discoveries in physics, the former in and the latter in Szilard, a Hungarian, was the chief physicist for the Manhattan Project, the nation's atom bomb project. Oppenheimer was the scientific director of the Los Alamos laboratory in the mountains of New Mexico during the war. The scientists there built the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The book, which offered little evidence other than Mr. Sudoplatov's recollections to back up its accusations, was excerpted in Time on April 25, , and ignited a global controversy as outraged scientists and historians rushed to defend the dead luminaries. Aspin had asked for the review on March Director, Louis J. Given Moscow's remarkable successes in placing Fuchs and Donald Maclean as atom spies, it would be brave to declare categorically that none of these four - Oppenheimer, Fermi, Szilard or Bohr - could possibly have been agents, or at least helpful sympathisers. But to assert, without supporting evidence, that they all were, is to smear them. These are four of the inspirational figures of modern physics: they deserve better. Independent Premium Comments can be posted by members of our membership scheme, Independent Premium. -

Wydawnictwa Drugiego Obiegu W Zbiorach Biblioteki Uniwersyteckiej W Toruniu

Wydawnictwa drugiego obiegu w zbiorach Biblioteki Uniwersyteckiej w Toruniu Lista druków zwartych, wydanych w latach 1976-1990 poza kontrolą władz cenzorskich PRL dostępnych w Bibliotece Uniwersyteckiej w Toruniu. Podstawę księgozbioru stanowiły trzy biblioteki niezależnych instytucji: Toruńskiej Oficyny, Toruńskiego Klubu Książki Nieocenzurowanej oraz Niezależnej Biblioteki i Archiwum w Toruniu. Zostały one uzupełnione o liczne dary krajowych instytucji naukowych, a przede wszystkim książki od osób prywatnych, często związanych z działalnością opozycyjną lat 1981-1989. Kolekcja obejmuje całokształt polskiej niezależnej produkcji wydawniczej poza kontrolą władz PRL. Dokumentuje zarówno dzieje podziemnego ruchu wydawniczego po 1976 roku, jak również reprezentuje całą gamę tematyczną ówczesnego niezależnego życia intelektualnego kraju. Wydawnictwa drugiego obiegu wydawniczego udostępniane są na miejscu w Czytelni Głównej. Stan na 21.11.2018 roku. 11 listopada 1918-1988. [Wrocław] : Wolni i Solidarni : Solidarność Walcząca, [1988]. (Wrocław 1. : druk: Agencja Informacyjna Solidarności Walczącej). 11 Listopada 1918. Wkład Chełmszczyzny w dzieło Niepodległości. Śpiewnik pieśni patriotycznej i legionowej / Komisja Zakładowa Pracowników Oświaty i Wychowania NSZZ 2. "Solidarność" Regionu Chełmskiego. Chełm : Komitet Organizacyjny Obchodów Święta Niepodległości, 1981. 11 listopada : śpiewniczek pieśni patriotycznej. [Warszawa : Biblioteka Historyczna i 3. Literacka], 1979. 11 listopada : śpiewniczek pieśni patriotycznych. Warszawa ; Gdańsk : Biblioteka Historyczno- 4. Literacka, 1981. 11 listopada : śpiewniczek pieśni patriotycznych. Warszawa ; Gdańsk : Biblioteka Historyczno- 5. Literacka, 1981. 6. 12 lat katorgi / Adolf Popławski. [Toruń] : Kwadrat, 1988. 13. Brygada Armii Krajowej Okręgu Wileńskiego / Adam Walczak ps. "Nietoperz". [S.l. : 7. s.l., ca 1985]. 8. 13 dni nadziei / Sandor Kopacsi. [S.l. : s. n., 1981]. 13 dni nadziei : Węgry 1956 / Sandor Kopăcsi. [Warszawa] : Oficyna Wydawnicza Post 9. Scriptum, [1983]. 13 dni nadziei : Węgry 1956 / Sandor Kopăcsi. -

PMA Polonica Catalog

PMA Polonica Catalog PLACE OF AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER DATE DESCRIPTION CALL NR PUBLICATION Concerns the Soviet-Polish War of Eighteenth Decisive Battle Abernon, De London Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd. 1931 1920, also called the Miracle on the PE.PB-ab of the World-Warsaw 1920 Vistula. Illus., index, maps. Ackermann, And We Are Civilized New York Covici Friede Publ. 1936 Poland in World War I. PE.PB-ac Wolfgang Form letter to Polish-Americans asking for their help in book on Appeal: "To Polish Adamic, Louis New Jersey 1939 immigration author is planning to PE.PP-ad Americans" write. (Filed with PP-ad-1, another work by this author). Questionnaire regarding book Plymouth Rock and Ellis author is planning to write. (Filed Adamic, Louis New Jersey 1939 PE.PP-ad-1 Island with PE.PP-ad, another work by this author). A factual report affecting the lives Adamowski, and security of every citizen of the It Did Happen Here. Chicago unknown 1942 PA.A-ad Benjamin S. U.S. of America. United States in World War II New York Biography of Jan Kostanecki, PE.PC-kost- Adams , Dorothy We Stood Alone Longmans, Green & Co. 1944 Toronto diplomat and economist. ad Addinsell, Piano solo. Arranged from the Warsaw Concerto New York Chappell & Co. Inc. 1942 PE.PG-ad Richard original score by Henry Geehl. Great moments of Kosciuszko's life Ajdukiewicz, Kosciuszko--Hero of Two New York Cosmopolitan Art Company 1945 immortalized in 8 famous paintings PE.PG-aj Zygumunt Worlds by the celebrated Polish artist. Z roznymi ludzmi o roznych polsko- Ciekawe Gawedy Macieja amerykanskich sprawach. -

Przewodnik Miejsc Spoczynku Żołnierzy Armii Krajowej Na Nowogródczyźnie I Grodzieńszczyźnie

PRZEWODNIK MIEJSC SPOCZYNKU ŻOŁNIERZY ARMII KRAJOWEJ NA NOWOGRÓDCZYŹNIE I GRODZIEŃSZCZYŹNIE PRZEWODNIK MIEJSC SPOCZYNKU ŻOŁNIERZY ARMII KRAJOWEJ NA NOWOGRÓDCZYŹNIE I GRODZIEŃSZCZYŹNIE KAZIMIERZ KRAJEWSKI ZWIĄZEK WALKI ZBROJNEJ I ARMIA KRAJOWA NA GRODZIEŃSZCZYŹNIE I NOWOGRÓDCZYŹNIE NOWOGRÓDZKI OKRĘG ZWZ-AK © Copyright by Fundacja Pomocy i Więzi Polskiej „Kresy RP” Podziemna praca niepodległościowa na Ziemi Nowogródzkiej rozpoczęła się w okresie pierwszej Warszawa 2020 okupacji sowieckiej 1939-1941. Powstało wówczas kilka działających równolegle organizacji, stop- Autor: dr Kazimierz Krajewski niowo wchłanianych przez ZWZ. Były to m.in. Związek Patriotów Polskich (Lida), Polska Organizacja Redakcja: Aneta Hoffmann, Denis Zwonik Wojskowa (Baranowicze), organizacja Kleofasa Piaseckiego i Polski Sztab Autonomiczny oraz szereg Projekt graficzny: Daniel Górnicki Brand mniejszych grupek podziemnych. Straty poniesione w wyniku działalności NKWD były ogromne, znaczna część struktur podziemnych została rozbita lub uległa dezorganizacji. Należy odnotować też, Str. I okładki: cmentarz poległych żołnierzy AK w Surkontach i ppłk Maciej Kalenkiewicz na koniu (fotomontaż) że na Nowogródczyźnie działała polska partyzantka zwalczająca sowiecki aparat represyjny i admini- stracyjny (grupy partyzanckie działały m.in. w Puszczy Nalibockiej oraz w lasach powiatów lidzkiego Wydawca: i szczuczyńskiego). Większość z nich została rozbita już w połowie 1940 r., jednak kilka dotrwało do Fundacja Pomocy i Więzi Polskiej „Kresy RP” wybuchu wojny niemiecko-sowieckiej w czerwcu 1941 r. ul. Zielna 39, 00-108 Warszawa http://akfundacjakresy.pl/ email: [email protected] Zadanie odbudowy polskiej konspiracji niepodległościowej na Nowogródczyźnie przypadło mjr./ ppłk Januszowi Szulcowi vel Szlaskiemu „Prawdzicowi”, „Borsukowi”, który sprawował tę funkcję w okre- Druk: Marka Krzysztof Gąsior sie od października 1941 do 12 czerwca 1944 r. Do grona jego najbliższych współpracowników należeli kpt. -

In Soviet Poland and Lithuania

IN SOVIET POLAND AND LITHUANIA By DAVID GRODNER IGID censorship and the absence of accredited news correspond- ents have made it impossible for American readers to learn R" what is really happening to Jews in Soviet Poland and Lith- uania. The impression that Polish refugees have found a friendly home in these areas is fostered largely by Communist propaganda, which has publicized the letters of those elated by their escape from Nazi Poland or those who had the good fortune to make a fair ad- justment under the new conditions. Having spent at least six months in Soviet Poland and more than that time in Lithuania, including the period of its occupation, I feel it my duty to tell what I have seen happen to the religious, communal and cultural life of Jews under their new Soviet masters. In particular, more ought to be known about the fate of at least one hundred thousand Polish Jewish refugees who sought aliaven from the Nazi invaders only to be driven mercilessly to the frozen tundras of Siberia. Newspapers in the United States have exaggerated the number of Jews in Soviet Poland. Altogether, there are about 1,200,000 Jews in Western Ukraine (former Galicia) and Western Byelorosya (White Russia). In addition, approximately 500,000 Jews fled there from Nazi Poland. About 60% of these refugees, it must be noted, arrived before the Red Army entered the country. On the night of September 6, 1939, the propaganda chief of the Polish Army announced over the radio that Warsaw was to be evacuated and ordered all inhabitants of military age to leave the city.* (Later, it was rumored that this official was a German spy carrying out Nazi orders.) About 200,000 persons left Warsaw that night and headed for the Bug River, where the Polish Army was planning to make a last stand. -

Jewish Labor Bund's

THE STARS BEAR WITNESS: THE JEWISH LABOR BUND 1897-2017 112020 cubs בונד ∞≥± — A 120TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF THE FOUNDING OF THE JEWISH LABOR BUND October 22, 2017 YIVO Institute for Jewish Research at the Center for Jewish History Sponsors YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Jonathan Brent, Executive Director Workmen’s Circle, Ann Toback, Executive Director Media Sponsor Jewish Currents Executive Committee Irena Klepisz, Moishe Rosenfeld, Alex Weiser Ad Hoc Committee Rochelle Diogenes, Adi Diner, Francine Dunkel, Mimi Erlich Nelly Furman, Abe Goldwasser, Ettie Goldwasser, Deborah Grace Rosenstein Leo Greenbaum, Jack Jacobs, Rita Meed, Zalmen Mlotek Elliot Palevsky, Irene Kronhill Pletka, Fay Rosenfeld Gabriel Ross, Daniel Soyer, Vivian Kahan Weston Editors Irena Klepisz and Daniel Soyer Typography and Book Design Yankl Salant with invaluable sources and assistance from Cara Beckenstein, Hakan Blomqvist, Hinde Ena Burstin, Mimi Erlich, Gwen Fogel Nelly Furman, Bernard Flam, Jerry Glickson, Abe Goldwasser Ettie Goldwasser, Leo Greenbaum, Avi Hoffman, Jack Jacobs, Magdelana Micinski Ruth Mlotek, Freydi Mrocki, Eugene Orenstein, Eddy Portnoy, Moishe Rosenfeld George Rothe, Paula Sawicka, David Slucki, Alex Weiser, Vivian Kahan Weston Marvin Zuckerman, Michael Zylberman, Reyzl Zylberman and the following YIVO publications: The Story of the Jewish Labor Bund 1897-1997: A Centennial Exhibition Here and Now: The Vision of the Jewish Labor Bund in Interwar Poland Program Editor Finance Committee Nelly Furman Adi Diner and Abe Goldwasser -

Krzysztof A. Tochman

Krzysztof A. Tochman . Michał Fijałka urodził się 5 października 1915 r. w Izdeb- kach, pow. brzozowski, w rodzinie chłopskiej Józefa i Marii z d. Hućko. W latach 1922–1927 ukończył pięć klas szkoły powszechnej w Izdebkach, następnie rozpoczął naukę w dru- giej klasie gimnazjum w Brzozowie. Od 1930 r. uczył się w Państwowym Gimnazjum im. Królowej Zofii w Sanoku, gdzie został przyjęty do klasy czwartej. Egzamin dojrzałości złożył w 1935 r. Przez rok był zatrudniony jako robotnik fi- zyczny w kopalni nafty „Paula” w Mokrem k. Sanoka. Od 20 września 1936 do 20 września 1937 r. kształcił się na kur- sie podchorążych rezerwy piechoty przy 5. Pułku Strzelców Podhalańskich 22. DP Górskiej. Po wyjściu z wojska praco- wał w Związku Szlachty Zagrodowej, najpierw w Zarządzie Głównym w Przemyślu, a następnie jako instruktor oświatowy Związku Szlachty Zagrodowej w powiatach Turka n. Stryjem i Dobromil. Zmobilizowany w lipcu 1939 r. do WP, kampanię wrześniową 1939 r. odbył jako sierżant podchorąży, dowodząc plutonem w szeregach 5. Pułku Strzelców Podhalań- skich w armii „Kraków”, na szlaku od Trzebini przez Miechów i Busko. Po rozbiciu jednostki przez Niemców w okolicach Kolbuszowej (18 września) udał się do rodzin- nych Izdebek, jak głosi legenda – „na koniu i w pełnym oporządzeniu”. 20 października 1939 r. przeszedł granicę polsko-węgierską w okolicach Wetliny i został internowany w obozie dla osób cywilnych w miejscowości Szob nad Dunajem k. Esztergom. 6 listopada wyjechał do Budapesztu i na podstawie wyrobionego w kon- sulacie RP paszportu udał się pociągiem przez Jugosławię i Włochy do Francji. 17 listopada 1939 r. w punkcie zbornym w paryskich koszarach Bessières wstą- pił do Polskich Sił Zbrojnych pod dowództwem francuskim i skierowany został do . -

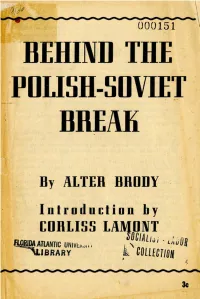

Behind the Polish-Soviet Break

,BEHIND THE POLISH-SOVIET BREAK By ALTER BRODY -I n I rod II eli 0 n h y [OBLISS LAl\fo~/~! " ~JlANTIG UNIV""".. , i '\ LI",. <HoUR - ISRARY ~ . COLLECTION , ~ • 3c l Introduction OVIETR USSIA'S severan ce of relations with the Polish S Government-in-Exile, over the Nazi-inspired charge that the Russians murdered 10,000 Polish army officers, sh ows clearly the danger to the United N ations of the splitting tac tics engineered by Hitler and definitely helped along by the general campaign of anti-Soviet propaganda carried on during recent months in Britain and America. According to the London Bureau of the N ew York Herald Tribune, " It is a safe assumption that the Poles would not have taken so tough an a tt itu de toward the Soviet Government if it had not been for the widespread support Americans have been giving them in the cases of H enry Ehrlich and Victor Alter." It is significant, too, to note, as Professor Lange of the Uni versity of Chicago has pointed out, that the American Friends of Poland, an anti-Soviet organization under the wing of the Polish Embassy, counts among its members some of America's foremost isolationists and America Firsters such as Colonel Langhom, its chairman; General Wood, Mr. John Cudahy, Mr. Robert Hall McCormick and Miss Lucy Martin. These individuals have all been leading advocates of a negotiated peace with Hitler at the expense of Soviet Russia. Mr. Walter Lippmann well sums up the matter in his column "T od ay' and Tomorrow" when h e states that the net effect of American public opinion has . -

HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS of SOVIET Terroi\

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I --' . ' J ,j HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF SOVIET TERROi\ .. HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBOOMMITTEE ON SECURITY AND TERRORISM OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED ST.A.g;ES;~'SEN ATE NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF SOVIET TERRORISM JUNE 11 AND 1~, 1981 Serial No.. J-97-40 rinted for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary . ~.. ~. ~ A\!?IJ.ISIJl1 ~O b'. ~~~g "1?'r.<f~~ ~l~&V U.R. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1981 U.S. Department ':.~ Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permissic;m to reproduce this '*ll'yr/gJorbJ material has been CONTENTS .::lrante~i,. • . l-'ubllC Domain UTIltea~tates Senate OPENING STATEMENTS Page to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Denton, Chairman Jeremiah ......................................................................................... 1, 29 Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the 00j5) I i~ owner. CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF WITNESSES JUNE 11, 1981 COMMI'ITEE ON THE JUDICIARY Billington, James H., director, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars ......................................................................................................................... 4 STROM THU'lMOND;1South Carolina, Chairman Biography .................................................................................................................. 27 CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, JR., Maryland JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL LAXALT Nevada EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JUNE 12, 1981 ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia. Possony, Stefan T., senior fellow (emeritus), Hoover Institution, Stanford Uni- ROBERT DOLE Kansas HOWARD M. -

Drapieżne Ptaszki

Drapieżne ptaszki yło ich zaledwie 316, ale zadanie mieli ambitne. nold von Lückner. Porozmawiał z Niemcem o froncie Jak się wyraził Winston Churchill – „podpalić Eu- wschodnim, po czym pozwolił się odwieźć na dwo- Bropę”. A w każdym razie okupowaną Polskę: tak rzec jego własną limuzyną. skutecznie poprowadzić działania dywersyjne, żeby Niemcy przestali się tu czuć bezpiecznie. Odpowiadamy na pytanie, co ukształtowało tych ludzi. Z jakich środowisk pochodzili, jak wyglądało Cichociemni, spadochroniarze Armii Krajowej, ich wychowanie i edukacja w II Rzeczpospolitej. Opi- byli świetnie wyszkolonymi żołnierzami polskich sujemy szkolenie w Wielkiej Brytanii. Rysujemy pano- wojsk na Zachodzie. Wyselekcjonowani w Wielkiej ramę Polskiego Państwa Podziemnego, którego byli Brytanii, przeszli specjalistyczne kursy. Musieli być ważną częścią. wszechstronni; nie tylko skoczyć ze spadochronem w nocy w nieznanym terenie, ale i działać w obcym Losów wszystkich nie sposób opisać, toteż wybra- mieście, opracować zamachy na funkcjonariuszy liśmy kilkanaście postaci, aby za ich pośrednictwem III Rzeszy, zaplanować rozbicie niemieckiego więzie- pokazać różnorodność dróg wojennych i powojen- nia, opanowanie miasta, wysadzić most czy tory ko- nych całego pokolenia. lejowe, perfekcyjnie sfałszować dokumenty, strzelać z biodra jak rewolwerowcy, a w razie potrzeby nadać Po 1945 r. niektórzy cichociemni pozostanie wiadomość radiotelegraficzną. I mieli nauczyć, ile się w kraju przypłacili życiem, inni wtopili się w tłum z tego da, żołnierzy Armii Krajowej. i przetrwali, jeszcze inni wybrali emigrację. O kilku słuch zaginął, nie wiadomo, czy jeszcze żyją. Ich por - Cichociemnych spadochroniarzy ochrzczono tret zbiorowy kreślimy w 75. rocznicę pierwszego sko- mianem ptaszków, ale były to ptaszki drapieżne. ku do Polski. Na tę zresztą okoliczność 2016 r. został Słynęli z zachowania zimnej krwi w najtrudniej- ogłoszony przez Sejm RP Rokiem Cichociemnych Spa- szych sytuacjach. -

Z Kart Historii

Z KART HISTORII Szymon Niedziela AKCJA BURZA1 1944 NA OBSZARZE WILEŃSKO-NOWOGRÓDZKIM AK Idea powstania powszechnego i wzmożonej akcji sabotażowo-dywersyjnej Celem działalności politycznych i wojskowych struktur Polskiego Pań- stwa Podziemnego było wzniecenie we właściwym momencie powstania powszechnego przeciwko Niemcom. Początkowo ogromne nadzieje pokładano we Francji. Jak pisał Stanisław Dygat w ,,Jeziorze Bodeńskim” – nad Wisłą bardziej wierzono w sukces armii francuskiej niż nad Sekwaną. W powieści Kazimierza Brandysa ,,Miasto niepokonane” czytamy, iż w Warszawie czeka- no oraz tęskniono za Marną, Sommą, Verdun oraz triumfującym marszałkiem Philippem Pétain. Spodziewano się ofensywy na wiosnę 1940 r., co byłoby sprzężone z uaktywnieniem organizacji konspiracyjnych w okupowanym kraju. Na ulicach miast mówiono z radością – ,,im słoneczko wyżej, tym Sikorski bliżej”. Każde polskie serce przepełnione było nadzieją, że Francuzi przyjdą razem z naszymi oddziałami, a w kraju wybuchnie ogólnonarodowe powstanie. Podobnie było w 1806 r. gdy Napoleon wkraczał do Wielkopolski, przywitał go bohaterski zryw niepodległościowy Wielkopolan. Pamiętano również powrót Błękitnej Armii gen. Józefa Hallera. Niestety klęska armii francuskiej rozwiała 1 Akcja Burza w historiografii nazywana jest również Operacją Burza i Planem Burza. W depeszy premiera Stanisława Mikołajczyka do Delegata Rządu na Kraj z 4 VII 1944 r. pojawia się też określenie ,,powstanie” – ,,Ponieważ walka i tak rozgo- rzała na wschodzie, czy nie warto by już tego nazwać powstaniem?”. Za: T. Strzembosz, Rzeczpospolita Podziemna Społeczeństwa polskie a państwo podziemne 1939–1945, Warszawa 2000, s. 259 oraz Armia Krajowa w Dokumentach 1939–45, T. III kwiecień 1943–lipiec 1944, s. 496. 112 te nadzieje. Nie sprawdziły się zapewnienia gen. Sikorskiego, że ,,prędzej Alpy się rozstąpią niż Francja przegra”.