Figures of the Eternal Return and the Apocalypse in Chilean Post-Dictatorial Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Violence and Politics

Journal of Political Science Brooklyn College 2008 Violence and Politics Guernica by Pablo Picasso Journal of Political Science Brooklyn College 2008 Violence and Politics Editors: Jamie Hagen & Shani A. Hines Faculty Advisor: Professor Mark Ungar Contents: ___________________________________________ I. Rationale for State Deployment of Private Military Companies By: Joshua Bolden II. Swedish Immigration Policies: An Extension of Violence in Iraq By: Lisa Carlborn III.Turkey and the Kurds: An Ongoing Conflict in a Troubled Region By: Sabina Ibragimova IV. Introduction to the Art Review: By: Shani A. Hines V. Art Review: New York Exhibits and CUNY Artists on Violence and Politics By: Shani A. Hines and Jamie Hagen VI Book Review: Current Texts By: Jamie Hagen VII Focus on Genocide: The Case of Darfur By: Jamie Hagen VIII. Spotlight Piece: The Refugee Law Project- Issues of Reconciliation & Rebuilding After the Genocide in Rwanda By: Shani A. Hines I. Rationale for State Deployment of Private Military Companies The monopoly of state controlled armed forces used By: Joshua Bolden in wars is a relatively recent phenomenon. Introduction: Historically, the use of mercenaries predominated Since the 1990s, private military companies armies in pre-industrial Europe. The system of (PMCs) have taken a crucial role in several conflicts, scutage in twelfth century England allowed for men in some cases displacing traditional military forces. with adequate means to legally avoid military service The use of PMCs is not restricted to a particular type in exchange for a payment to the king; thus, the of state, with both impoverished and powerful states revenue from scutage was used to pay professional utilizing their services. -

CLARK-DISSERTATION.Pdf (1.724Mb)

Copyright by Meredith Gardner Clark 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Meredith Gardner Clark Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Warping the Word and Weaving the Visual: Textile Aesthetics in the Poetry and the Artwork of Jorge Eduardo Eielson and Cecilia Vicuña Committee: Luis Cárcamo Huechante, Co-Supervisor Enrique Fierro, Co-Supervisor Jossiana Arroyo Jill Robbins Charles Hale Regina Root Warping the Word and Weaving the Visual: Textile Aesthetics in the Poetry and the Artwork of Jorge Eduardo Eielson and Cecilia Vicuña by Meredith Gardner Clark, B.A.; M. A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my family and my friends. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge all of the professors on my committee who have guided me through this research project from its germination to its completion. I thank Enrique Fierro for his unwavering support, countless hours of conversation and for being my poetry professor. My tremendous gratitude also goes to Luis Cárcamo Huechante for his scholarly expertise, his time and his attention to detail. To Jossiana Arroyo and Jill Robbins, I offer my appreciation for their support from day one, and I would also like to thank Regina Root for providing me with valuable resources regarding Andean textiles and Charles Hale for taking a chance on an unknown graduate student. My gratitude is also in store for Cecilia Vicuña for her support and for her artistic vision. -

The Post-Dictatorial Thriller Form

THE POST-DICTATORIAL THRILLER FORM A Dissertation by AUDREY BRYANT POWELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies The Post-Dictatorial Thriller Form Copyright 2012 Audrey Bryant Powell THE POST-DICTATORIAL THRILLER FORM A Dissertation by AUDREY BRYANT POWELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Alberto Moreiras Committee Members, Juan Carlos Galdo Teresa Vilarós Andrew Kirkendall Head of Department, Alberto Moreiras May 2012 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies iii ABSTRACT The Post-Dictatorial Thriller Form. (May 2012) Audrey Bryant Powell, B.A., Baylor University; M.A., Baylor University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Alberto Moreiras This dissertation proposes a theoretical examination of the Latin American thriller through the framework of post-dictatorial Chile, with a concluding look at the post civil war Central American context. I define the thriller as a loose narrative structure reminiscent of the basic detective story, but that fuses the conventional investigation formula with more sensational elements such as political violence, institutional corruption and State terrorism. Unlike the classic form, in which crime traditionally occurs in the past, the thriller form engages violence as an event ongoing in the present or always lurking on the narrative horizon. The Chilean post-dictatorial and Central American postwar histories contain these precise thriller elements. Throughout the Chilean military dictatorship (1973-1990), the Central American civil wars (1960s-1990s) and the triumph of global capitalism, political violence emerges in diversified and oftentimes subtle ways, demanding new interpretational paradigms for explaining its manifestation in contemporary society. -

OD 1413 DFM.Pmd

CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS DE LA NACION O.D. Nº 1.413 1 SESIONES DE PRORROGA 2008 ORDEN DEL DIA Nº 1413 COMISION DE CULTURA Impreso el día 9 de diciembre de 2008 Término del artículo 113: 18 de diciembre de 2008 SUMARIO: Revista “PROA en las Letras y en las INFORME Artes”, de ALLONI/PROA Editores. Declaración de interés de la Honorable Cámara. Genem. (5.835- Honorable Cámara: D.-2008.) La Comisión de Cultura ha considerado el pro- yecto de declaración de la señora diputada Genem, Dictamen de comisión por el que se declara de interés de la Honorable Cá- mara la revista “PROA en las Letras y en las Artes” Honorable Cámara: de ALLONI/PROA Editores. Las señoras y señores diputados, al iniciar el estudio de esta iniciativa, han La Comisión de Cultura ha considerado el pro- tenido en cuenta que por su vasta trayectoria la re- yecto de declaración de la señora diputada Genem, vista “PROA en las Letras y en las Artes” es consi- por el que se declara de interés de la Honorable Cá- derada decana de los medios literarios de América. mara la revista “PROA en las Letras y en las Ar- Su fundación data de 1922 por iniciativa de Jorge tes”, de ALLONI/PROA Editores; y, por las razones Luis Borges, Macedonio Fernández y Ricardo expuestas en el informe que se acompaña y las que Güiraldes; y, desde 1988, recorre su tercera etapa dará el miembro informante, aconseja la aprobación con una frecuencia bimestral, una tirada de 15.000 del siguiente ejemplares y manteniendo el formato de libro, que le conserva sus características literarias y estéticas. -

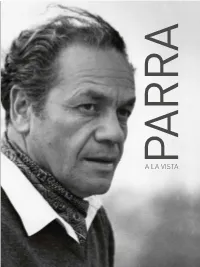

Parra-A-La-Vista-Web-2018.Pdf

1 LIBRO PARRA.indb 1 7/24/14 1:24 PM 2 LIBRO PARRA.indb 2 7/24/14 1:24 PM A LA VISTAPARRA 3 LIBRO PARRA.indb 3 7/24/14 1:24 PM 4 LIBRO PARRA.indb 4 7/24/14 1:24 PM A LA VISTAPARRA 5 LIBRO PARRA.indb 5 7/24/14 1:24 PM PARRA A LA VISTA © Nicanor Parra © Cristóbal Ugarte © AIFOS Ediciones Dirección y Edición General Sofía Le Foulon Investigación Iconográfica Sofía Le Foulon Cristóbal Ugarte Asesoría en Investigación María Teresa Cárdenas Textos María Teresa Cárdenas Diseño Cecilia Stein Diseño Portada Cristóbal Ugarte Producción Gráfica Alex Herrera Corrección de Textos Cristóbal Joannon Primera edición: agosto de 2014 ISBN 978-956-9515-00-2 Esta edición se realizó gracias al aporte de Minera Doña Inés de Collahuasi, a través de la Ley de Donaciones Culturales, y el patrocinio de la Corporación del Patrimonio Cultural de Chile Edición limitada. Prohibida su venta Todos los derechos reservados Impreso en Chile por Ograma Impresores Ley de Donaciones Culturales 6 LIBRO PARRA.indb 6 7/24/14 1:24 PM ÍNDICE Presentación 9 Prólogo 11 Capítulo I | 1914 - 1942 NICANOR SEGUNDO PARRA SANDOVAL 12 Capítulo II | 1943 - 1953 EL INDIVIDUO 32 Capítulo III | 1954 - 1969 EL ANTIPOETA 60 Capítulo IV | 1970 - 1980 EL ENERGÚMENO 134 Capítulo V | 1981 - 1993 EL ECOLOGISTA 184 Capítulo VI | 1994 - 2014 EL ANACORETA 222 7 LIBRO PARRA.indb 7 7/24/14 1:24 PM 8 capitulos1y2_ALTA.indd 8 7/28/14 6:15 PM PRESENTACIÓN odo comenzó con una maleta llena de fotografías de Nicanor Parra que su nieto Cristóbal Ugarte, el Tololo, encontró al ordenar la biblioteca de su abuelo en su casa de La Reina, después del terremoto Tde febrero de 2010. -

Department of Popular Culture Newsletter Vol. 3 Issue 2

SUMMER 2012 Department of Popular Culture Newsletter Vol. 3 Issue 2 Editors: Jeremy Wallach and Esther Clinton layout: Pamela Jean Wagner SPECIAL PRE-DEMOLITION EDITION Although it has only been a short while since we learned of the plan to demolish the Popular Culture Building, much has already been written about it. A petition has been started (and garnered over 1600 signatures) and there have been heated arguments back and forth concerning the historical significance of the house. The decision, which, once made public, appalled and saddened local residents, current students, alumni, faculty, and staff alike, is unlikely to be changed, and as of this writing both the provost and BGSU’s president have issued statements expressing their determination to proceed with the demolition as part of the administration’s Master Plan for the complete overhaul of BGSU’s campus. We are Graphics By Erin Holmberg assuming that anyone reading this newsletter is relatively informed on this issue. We also believe Volume 3, Issue 2 that it is not the place of a departmental newsletter In This Issue: to engage in activist work, no matter how we may ___________________________________ feel about something as individuals. Rather, we Report on The Ray Browne Conference on Popular hope to take this opportunity to mourn. For some Culture, Presented by the Popular Culture Scholars of us the house has been a more steadfast presence Association in our lives than friends or spouses. For some of us the house will always be a symbol of Ray Meet Marsha Olivarez, New Secretary to the Browne’s vision of a humanities that celebrates the Department of Popular Culture and Recent Graduate of BGSU dignity of the ordinary person and the power of regular people to creatively live their lives. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ono Tupuna, the richness of the ancestors. Multiples Landscapes Relationalities in Contemporary Indigenous Rapa Nui Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4kk483h5 Author Rivas, Antonia Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Ono Tupuna, the richness of the ancestors. Multiples Landscapes Relationalities in Contemporary Indigenous Rapa Nui By Antonia Rivas A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of degree requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Charles L Briggs, Co-Chair Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Co-Chair Professor Laura Nader Professor Leti P Volpp Summer 2017 Abstract Ono Tupuna, the richness of the ancestors. Multiples Landscapes Relationalities in Contemporary Indigenous Rapa Nu By Antonia Rivas Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Charles Briggs, Co-Chair Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Co-Chair Contemporary Rapa Nui is formed by a multiple and complex set of interactions, encounters, and circumstances that comprise the core of their indigenous identity, like many other indigenous people's realities. In this dissertation, I argue that there is not a simple or straightforward way of thinking about indigenous identities without falling into the trap of essentialism and stereotyping. Indigenous people are not what remained of ancestral civilizations, nor are they either invented nor folklorized commodities produced by ―neo-shamanism‖ discourses. Recent theoretical contributions to the understanding of the relationship of native peoples with their territories have been fundamental to rethinking the meanings of indigeneity, but I argue that they continue to essentialize indigenous people relations with their past and the ways in which they are understood in the present. -

Alegorías De La Derrota: La Ficción Postdictatorial Y El

www.philosophia.cl / Escuela de Filosofía de la Universidad ARCIS ALEGORÍAS DE LA DERROTA: LA FICCIÓN POSTDICTATORIAL Y EL TRABAJO DEL DUELO Idelber Avelar www.philosophia.cl / Escuela de Filosofía de la Universidad ARCIS 2 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN: ALEGORÍA Y POSTDICTADURA................................1 1. EDIPO EN TIEMPOS POSAURÁTICOS: MODERNIZACIÓN Y DUELO EN EL BOOM HISPANOAMERICANO..........29 2. LA GENEALOGÍA DE UNA DERROTA 2.1 - La cultura letrada bajo dictadura......................................................51 2.2 La teoría del autoritarismo como fundamento de las “transiciones” conservadoras......................................................….............................76 2.3 El giro naturalista y el imperativo confesional......................................…89 2.4. La alegoría como fin epocal de lo mágico.............................................100 2.5 La disolución de la universidad en la universalidad del mercado................116 3. UNA LECTURA ALEGÓRICA DE LA TRADICIÓN ARGENTINA...........129 4. DUELO Y NARRABILIDAD: UN CYBERPOLICIAL EN LA CIUDAD DE LOS MUERTOS......................162 5. PASTICHE, REPETICIÓN Y LA FIRMA FALSIFICADA DEL ÁNGEL DE LA HISTORIA..................202 6. SOBRECODIFICACIÓN DE LOS MÁRGENES: FIGURAS DEL ETERNO RETORNO Y DEL APOCALIPSIS......................245 7. BILDUNGSROMAN EN SUSPENSO: ¿QUIÉN APRENDE CON HISTORIAS Y VIAJES?....................................277 8. LA ESCRITURA DEL DUELO Y LA PROMESA DE RESTITUCIÓN............314 9. EPÍLOGO: POSTDICTADURA Y POSMODERNIDAD...........................349 -

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015)

New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005-2015) Paul Rumney Merchant St John’s College August 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. New Constructions of House and Home in Contemporary Argentine and Chilean Cinema (2005 – 2015) Paul Rumney Merchant This thesis explores the potential of domestic space to act as the ground for new forms of community and sociability in Argentine and Chilean films from the early twenty-first century. It thus tracks a shift in the political treatment of the home in Southern Cone cinema, away from allegorical affirmations of the family, and towards a reflection on film’s ability to both delineate and disrupt lived spaces. In the works examined, the displacement of attention from human subjects to the material environment defamiliarises the domestic sphere and complicates its relation to the nation. The house thus does not act as ‘a body of images that give mankind proofs or illusions of stability’ (Bachelard), but rather as a medium through which identities are challenged and reformed. This anxiety about domestic space demands, I argue, a renewal of the deconstructive frameworks often deployed in studies of Latin American culture (Moreiras, Williams). The thesis turns to new materialist theories, among others, as a supplement to deconstructive thinking, and argues that theorisations of cinema’s political agency must be informed by social, economic and urban histories. The prominence of suburban settings moreover encourages a nuancing of the ontological links often invoked between cinema, the house, and the city. The first section of the thesis rethinks two concepts closely linked to the home: memory and modernity. -

454 Avelar, Idelber. the Untimely Present

Reseñas los planteamientos de su maestro para hacer un alto y poner en evi- dencia una de las falencias más criticadas a los estudios culturales: la subordinación de la obra por la búsqueda de un discurso social o ideológico (122). Es muy importante que Bueno reconsidere este aspecto como uno de los puntos que más estridencias ha generado en otras academias, escuelas y corrientes del pensamiento latinoame- ricano, pues no en vano se presenta como problemático. ¿Puede una obra literaria sobrevivir a la pesquisa sociológica o de ideologías? Otra pregunta que queda abierta de forma muy pertinente en el texto. Para finalizar, están los dos ensayos en los que Bueno retoma una voz más familiar para recordar los años de Cornejo Polar a la cabecera del proyecto de universidad popular en Latinoamérica y, por otro lado, su trabajo con la Casa de la Cultura de Arequipa. El autor rescata del investigador su fuerte interés por impulsar y expandir la educación hasta las clases sociales más desfavorecidas, siendo coherente con su pensamiento de que la academia no se alimenta solamente de clases altas, sino de la afortunada mezcla entre ambas y la aceptación de una cultura propia y real entre la población de una ciudad y un país. Antonio Cornejo Polar, según el homenaje que se le hace en esta recopilación, es una pieza clave para poder hacer un acerca- miento a lo que ha significado la producción intelectual de Latinoamérica en los últimos cuarenta años. Es importante rescatar de este texto el interés por abrir las miradas de los lectores hacia otros ámbitos que, en oportunidades, no han sido tomados en cuen- ta de manera ferviente por algunos campos de la academia y que pueden aportar diferentes perspectivas al debate sobre la construc- ción de discursos en torno a la cultura latinoamericana. -

Redalyc.Avelar, Idelber. the Untimely Present: Postdictatorial Latin

Literatura: teoría, historia, crítica ISSN: 0123-5931 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia Nossa, Julián Avelar, Idelber. The Untimely Present: Postdictatorial Latin American Fiction and the Task of Mourning . Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999. 293 págs. Literatura: teoría, historia, crítica, núm. 8, 2006, pp. 454-464 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=503750721023 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Reseñas los planteamientos de su maestro para hacer un alto y poner en evi- dencia una de las falencias más criticadas a los estudios culturales: la subordinación de la obra por la búsqueda de un discurso social o ideológico (122). Es muy importante que Bueno reconsidere este aspecto como uno de los puntos que más estridencias ha generado en otras academias, escuelas y corrientes del pensamiento latinoame- ricano, pues no en vano se presenta como problemático. ¿Puede una obra literaria sobrevivir a la pesquisa sociológica o de ideologías? Otra pregunta que queda abierta de forma muy pertinente en el texto. Para finalizar, están los dos ensayos en los que Bueno retoma una voz más familiar para recordar los años de Cornejo Polar a la cabecera del proyecto de universidad popular en Latinoamérica y, por otro lado, su trabajo con la Casa de la Cultura de Arequipa. El autor rescata del investigador su fuerte interés por impulsar y expandir la educación hasta las clases sociales más desfavorecidas, siendo coherente con su pensamiento de que la academia no se alimenta solamente de clases altas, sino de la afortunada mezcla entre ambas y la aceptación de una cultura propia y real entre la población de una ciudad y un país. -

Dossier Nicanor Parra

Nicanor Parra, Premio Cervantes 2011 Página 1 de 20 Nicanor Parra, Premio Cervantes 2011 Contenido BIOGRAFÍA .................................................................................................................................................... 3 OBRA LITERARIA ........................................................................................................................................... 5 ANTIPOESÍA .............................................................................................................................................. 5 OBRAS .................................................................................................................................................. 7 OBRAS MÁS DESTACADAS ........................................................................................................................ 8 CANCIONERO SIN NOMBRE (1937) ...................................................................................................... 8 POEMAS Y ANTIPOEMAS (1954). ......................................................................................................... 8 LA CUECA LARGA (1958). ..................................................................................................................... 8 VERSOS DE SALÓN (1962) .................................................................................................................... 9 OBRA GRUESA (1969). ........................................................................................................................