I Ntroduct Ion This Thesis Is Ahout R Villrge Society and Its Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annexure-VI-Eng Purba Bardhaman Corrected Final Final.Xlsx

Annexure-6 (Chapter 2, para 2.9.1) LIST OF POLLING STATIONS For 260-Bardhaman Dakshin Assembly Constituency within 39-Bardhaman-Durgapur Perliamentry Constitutency Wheather Sr. No. for all voters of the Building in which will be Locality Polling Area or men only Polling located or women Station only 1 2 3 4 5 Kamal Sayar, Ward no. 26, Burdwan Municipality University Engineering 1. Both side of Kamal Sayar, 2. East Side of 1 For all voters Sadar Burdwan, Pin-713104. College, Kamal Sayar Research Hostel road Goda, Ward No. 26, Burdwan Municipality Sadar Goda Municipal F.P. School (R- 1.Goda Kajir Hat, 2. Goda Sib tala, 3. 2 For all voters Burdwan, Pin-713102. 1) Tarabag, 4. Golapbag Goda, Ward No. 26, Burdwan Municipality Sadar Goda Municipal F.P. School (R- 1. Goda Koit tala, 2. Goda Kumirgorh, 3. 3 For all voters Burdwan, Pin-713102. 2) Goda Jhumkotala, 4. Goda Khondekar para, 1. Banepukur Dakshinpar, 2. Banepukur Goda, Ward No. 26, Burdwan Municipality Sadar pashimpar, 3. Das para, 4. Simultala, 5. 4 Goda F.P. School (R-1) For all voters Burdwan, Pin-713102. Banepukur purba para, 6. Goda Roy colony, 7. Goda Majher para, 8. Goda Dangapara. 1. Goda Mondal Para, 2. Goda Molla Para, Goda, Ward No. 26, Burdwan Municipality Sadar 5 Goda F.P. School (R-2) 3.Dafadar Para, 4. Goda Bhand para, 5. Goda For all voters Burdwan, Pin-713102. Bizili par, 6. Nuiner Par 1. Goda math colony, 2. Goda kaibartya para, 3. Goda sibtala, 4. Goda mali para, 5. Goda Goda, Ward No. -

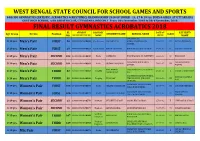

FINAL RESULT GYMNASTICS ACROBATICS 2018 SL STUDENT DISTRICT DATE of FATHER's Age Group Events Position STUDENT NAME SCHOOL NAME CLASS NO

WEST BENGAL STATE COUNCIL FOR SCHOOL GAMES AND SPORTS 64th SSG GYMNASTICS (ARTISTIC, ACROBATICS & RHYTHMIC) CHAMPIONSHIP 2018 OF UNDER - 14, 17 & 19 yrs. BOYS & GIRLS AT UTTARPARA GOVT.HIGH SCHOOL, with SARATHI CLUB, UTTARPARA, HOOGHLY From 01st November 2018 to 03rd November, 2018 FINAL RESULT GYMNASTICS ACROBATICS 2018 SL STUDENT DISTRICT DATE OF FATHER'S Age Group Events Position STUDENT NAME SCHOOL NAME CLASS NO. REGISTRATION NO NAME BIRTH NAME JAHANNAGAR U-19 yrs. Men's Pair FIRST 20 09-18-19-01-08634 Bardhaman RAJ DEBNATH KUMARANANDA HIGH 23-07-02 XII RATAN DEBNATH SCHOOL U-19 yrs. Men's Pair FIRST 19 09-18-19-01-08627 Bardhaman BAPAN DEBNATH KURICHA T.D. HIGH SCHOOL 06-01-05 IX TARANI DEBNATH U-19 yrs. Men's Pair SECOND 103 10-18-19-01-08368 Nadia RAHUL DAS KABI BIJOYLAL HS INSTITUTE 23-11-02 XI BIMAL DAS NABADWIP HINDU HIGH SHYAM SUNDAR 10-18-19-01-08369 Nadia SOUMALYA BISWAS 26-01-07 VII U-19 yrs. Men's Pair SECOND 104 SCHOOL BISWAS AMIT KUMAR TELENIPARA M.G. VIDYAPITH 12-18-17-01-08267 Hooghly 03-01-02 X ASHOK CHOWDHURY U-17 yrs. Men's Pair THIRD 32 CHOWDHURY H.S. CHANDERNAGORE KANAILAL SUBHAS CHANDRA 12-18-14-01-08268 Hooghly SUJAL ROY VIDYAMANDIR (ENGLISH 13-09-06 VII U-14 yrs. Men's Pair THIRD 30 ROY SECTION) NABADWIP TARASUNDARI 10-18-19-02-08373 Nadia PARAMITA DEBNATH 31-07-06 VII GAUTAM DEBNATH U-19 yrs. Women's Pair FIRST 108 GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL NABADWIP TARASUNDARI BIJAN KUMAR 10-18-19-02-08372 Nadia DEBASMITA SARKAR 18-11-02 XI U-19 yrs. -

Chapter Ii History Rise and Fall of the Bishnupur Raj

CHAPTER II HISTORY RISE AND FALL OF THE BISHNUPUR RAJ The history of Bankura, so far as it is known, prior to the period of British rule, is identical with the history of the rise and fall of the Rajas of Bishnupur, said to be one of the oldest dynasties in Bengal. "The ancient Rajas of Bishnupur," writes Mr. R. C. Dutt, "trace back their history to a time when Hindus were still reigning in Delhi, and the name of Musalmans was not yet heard in India. Indeed, they could already count five centuries of rule over the western frontier tracts of Bengal before Bakhtiyar Khilji wrested that province from the Hindus. The Musalman conquest of Bengal, however, made no difference to the Bishnupur princes. Protected by rapid currents like the Damodar, by extensive tracts of scrub-wood and sal jungle, as well as by strong forts like that of Bishnupur, these jungle kings were little known to the Musalman rulers of the fertile portions of Bengal, and were never interfered with. For long centuries, therefore, the kings of Bishnupur were supreme within their extensive territories. At a later period of Musalman rule, and when the Mughal power extended and consolidated itself on all sides, a Mughal army sometimes made its appearance near Bishnupur with claims of tribute, and tribute was probably sometimes paid. Nevertheless, the Subahdars of Murshidabad never had that firm hold over the Rajas of Bishnupur which they had over the closer and more recent Rajaships of Burdwan and Birbhum. As the Burdwan Raj grew in power, the Bishnupur family fell into decay; Maharaja Kirti Chand of Burdwan attacked the Bishnupur Raj and added to his zamindari large slices of his neighbour's territories. -

District Election Officer Purba Bardhaman

District Election Management Plan General Election to West Bengal Legislative Assembly - 2021 District Election Officer Purba Bardhaman Md. Enaur Rahman, WBCS (Exe.) District Magistrate & District Election Officer Purba Bardhaman, West Bengal, PIN – 713101 Phone No :- (Office) : 0342-2662428 (Residence) : 0342-2625700/2625702 Fax : 91-342-2625703 PBX : 2662408-412 Extn. 100 E-Mail ID :- [email protected] Foreword The process of General Election to WBLA-21 having started, this booklet on District Election Management Plan is being published keeping in mind the various facts of the works related to Election in the Purba Bardhaman District. This booklet not only contains the basic data of the district regarding Election but also focuses on the analysis of data, as well as the plans we have kept ready as we approach nearer to conduct of election. Many of the data being dynamic, and changes almost daily. The book also contains maps developed by NRDMS Section of this Office which will be helpful for locating the Polling Stations. This booklet is an amalgamation of summary of plans and preparedness of different Cells like EVM, Polling Personnel, Complaint Monitoring, Training, Expenditure Monitoring, MCC, IT, Postal Ballot (Absentee Voter) etc, each cell having their detail plans at their ends. Purba Bardhaman The 29th March, 2021. Md. Enaur Rahman, WBCS (Exe.) CONTENTS District the Purba Bardhaman ......................................................................................................5 Administrative Map ....................................................................................................................7 -

Purba Bardhaman District at a Glance

PURBA BARDHAMAN DISTRICT AT A GLANCE The name Burdwan is the anglicized form of Barddhaman. (also spelled as Burdwan or Burdhman) is a district in West Bengal. There are two schools of thoughts about the name Barddhaman. It might have been named after the 24th Jaina Tirthankar. According to Kalpasutra of the Jains, Mahavira spent sometime in Astikagram which was formerly known as Barddhaman. According to the second school, Barddhaman means prosperous growth centre. In the progress of Aryanisation from Upper Ganges valley, the frontier colony was called Barddhaman as a landmark of growth and prosperity. The name came to stay as the Aryans failed to consolidate their gains further east. District : Purba Bardhaman, State : West Bengal Social & Resource Map Showing River System of Purba Bardhaman District The main towns of the district is Burdwan, Kalna & Katwa Geography: Total Geographical Area: 5432.69 sq. km. The district extends from 22°56' to 23°53' N latitude and from 86°48' to 88°25' E longitudes. Lying within Burdwan Division, the district is bounded on the north by Birbhum and Murshidabad, on the east by Nadia, on the south by Hooghly, Bankura and Purulia and on the west by Paschim Bardhaman districts. RIVERS : The river system in Purba Barddhaman includes the Bhagirathi-Hooghly in the east, the Ajoy and its tributaries in the north and the Dwarakeswar, the Damodar and its branches in the south-west. Besides, there are innumerable Khals and old river beds all over the area. WATER RESOURCES : There are many tanks, wells, canals, swamps and bils are found all over the district. -

MSW (July) 2014.P65

INDEX 1. The Concept of Open University 3 2. Netaji Subhas Open University : Vision & Mission 3 3. Recognition 4 4. Post-Graduate Courses : Rules and Regulation 5 i) Academic Session 5 ii) Admission Procedure 5 iii) Fees Structure 6 iv) Eligibility 6 v) Medium of Instructions 7 vi) Study Materials 7 vii) Method of Instruction 7 viii) Examination 8 ix) Change of Address / Study Centre 9 x) No Change of Subject 9 xi) Identity Card 9 xii) Cleared/Pass, Irregular Appearance, Review 9 5. Course Content 11 6. List of Study Centres 18 7. Application Form 1 2 1. The Concept of Open University The Open University represents an alternative approach to higher learning. It stands apart from a highly formal, institutionalized and centrally administered system of education. Its philosophy is built around the principles of universality, flexibility and innovativeness. Its ideas and institutions, its methods and procedures are all shaped accordingly. Conceptually, it can be viewed as a system drawing upon the best elements in formal and non-formal education. The ‘openness’ consists of a variety of features. First, it offers easy access to the learners. The entry requirement is not too exacting. A genuine interest in picking up knowledge is all that it expects. Consequently, it would try to embrace as many learners as possible. Second, its territorial reach is visibly wide. It aims at bringing education to the door-step of the learner, wherever he or she may be. Various methods of communication and contact are used for this purpose. The classroom of the University, thus, is as wide as the entire land it seeks to serve. -

Detailed Detailed Project Report ( Eport (DPR)

Detailed Project Report on Puraba Bardhhaman Coir Cluster – West Bengal Detailed Project Report (DPR) PurbaBardhaman Coir Cluster, West Bengal Submitted to Directorate of SFURTI Ministry of MSME, Government of India Submitted by PanuhatKarmaudyog Welfare Society, Panuhat, Katwa, PurbaBardhaman Prepared by Foundation for MSME Clusters (TA) USO House, 2nd Floor, USO Road, Shaheed Jeet Singh Marg, 6, Special Institutional Area, New Delhi – 110067 * A Detailed Project Report on Puraba Bardhhaman Coir Cluster – West Bengal Contents Chapter No Name Page Nos. 1 CLUSTER PROFILE 1 2 CLUSTER VALUE CHAIN MAPPING 10 3 MARKET ASSESSMENT AND DEMAND ANALYSIS 21 4 NEED GAP ANALYSIS 24 5 PROFILE OF THE IMPLEMENTING AGENCY 28 6 PROJECT CONCEPT AND STRATEGY FRAMEWORK 32 7 PROJECT INTERVENTION 34 8 SOFT INTERVENTION 37 9 HARD INTERVENTION 44 10 PROJECT COST AND MEANS OF FINANCE 59 11 PLAN FOR CONVERGENCE 61 12 ENHANCED PROJECT COST AND MEANS OF FINANCE 62 13 PROJECT TIMELINE 63 14 DETAILED BUSINESS PLAN 64 15 PROPOSED IMPLEMENTATION FRAMEWORK 70 16 EXPECTED IMPACT 73-74 ANNEXURE FINANCIAL DETAILS 75-99 MACHINERY QUOTATION 100-107 PLAN LAYOUT AND ESTIMATION 108-113 LAND REGISTRATION 114-128 SPV REGISTRATION 129-130 LIST OF ARTISANS 133-140 B Detailed Project Report on Puraba Bardhhaman Coir Cluster – West Bengal List of Acronyms CFTRI Central Food Technology Research Institute DoI Director of Industries DC-MSME Development Commissioner – Micro, Small and Medium enterprises DPR Detailed Project Report DSR Diagnostic Survey Report MSE-CDP Micro Small Enterprise -

BDP-2015 Final PDF.P65

INDEX 1. The Concept of Open University 3 2. Netaji Subhas Open University : Vision & Mission 4 3. Methods of Instruction 4 4. Language of Instruction 4 5. Academic Session 4 6. Bachelor’s Degree Programme 5 7. Eligibility Criteria 5 8. Admission Procedure 6 9. Change of Address / Study Centre 7 9A. No Change of Subject 7 10. Fees Structure 7 11. Study Centres & Student Support Services 7 12. Examination Pattern 8 13. Evaluation Method : ‘The Credit System’ 9 14. Scholarship 12 14A. Redressal and Student’s Grievance 12 15. List of Study Centres for BDP Courses 13 2 1. The Concept of Open University An open learning system is one in which the onus of learning is primarily on the students. Despite this, they are formally enrolled in a system which takes in other learners too. Thus, we draw a line of distinction between the above-mentioned category of students and (a) those borrowing books from Libraries and (b) those formally attached to a conventional university where classroom teaching is the principal mode of instruction. The Open University represents an alternative approach to higher learning. It stands apart from a highly formal, institutionalized and centrally administered system of education. Its philosophy is built around the principles of universality, flexibility and innovativeness. Its ideas and institutions, its methods and procedures are all shaped accordingly. Conceptually, it can be viewed as a system drawing upon the best elements in formal and non-formal education. The ‘openness’ consists of a variety of features. First, it offers easy access to the learners. The entry requirement is not too exacting. -

Administrative Report of General Section of Purba Bardhaman Collectorate for the Period from 01.04.2017 to 31.03.2018

Administrative Report of General Section of Purba Bardhaman Collectorate for the period from 01.04.2017 to 31.03.2018 1. Name of ADM in Charge Shri. Nikhil Nirmal,IAS (01.04.2017 – 31.03.2018) 2. Name of O/C Sri Utpal Kumar Ghosh, WBCS(Exe) (01.04.2017 to 07.09.2017) Smt Sutapa Naskar, WBCS (Exe.) (07.09.2017 to 31.03.2018) 3. Staff strength, sanctioned Sl No. Category of Staff Sanctioned Existing Staff Vacancy and in position, in case of post Vacancies, steps taken to fill 1. HA 01 01 Nil them up has to be 2. HC (Supervisor) 03 Nil 03 mentioned. 3. UDA 11 03 08 4. LDA 11 Nil 11 5. Telephone Operator Nil Nil Nil 6. B.T 01 01 Nil 7. C.C Staff 07 02 05 8. Gp-‘D’ 06 04 02 9. Contingent Menial -- --- -- 4. Nature of work assigned to a) Inspection & Audit b) Construction of Administrative Building /Treasury Building c) the section in brief. Examination of SSC (Central Govt.)/WBSSC/PSC/Police Recruitment Board/Madhyamik Examination/Higher Secondary Examination/Joint Entrance Examination of West Bengal Board/Joint Entrance Examination conducted by CBSE Board /JEE Advanced Examination conducted by IIT d) Parliamentary Quiz Competition e) Celebration of Republic Day/Independence Day/Martyrs Day f) Police Verification Report (Central Govt. Defence & Non-Defence, PSUs g) RTI & Education h) /VIP Programme i) Defence Welfare j) Samarthan Scheme – 2017 k) General Receiving l) Letter Despatch m) Domicile Certificate n) Income Certificate etc, 5. Acts & Rules & Regulation Right to Information Act, 2005 & as per requirement existing rules & others. -

S. No. Institute Name

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal CHANDRA SOURABH ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING 2 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal SINHA MOUSUMI ENGINEERING AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 3 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal GHOSH BAITALI ENGINEERING AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 4 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal DASGUPTA ARUN ENGINEERING AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 5 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal MANDAL HIMADRI ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY ENGG 6 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal SK HALIM ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY ENGG 7 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal BHAUMIK HEMENDRA ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 8 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal SINGH SANTOSH ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 9 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal GHOSH SOUMITA ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 10 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal GOSWAMI DEBAJYOTI ENGINEERING AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 11 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal BHOWMICK RAJIB ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING 12 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal BHATTACHARY DIPANKAR ENGINEERING AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY A TECHNOLOGY 13 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West Bengal DEBNATH JOY ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 14 CALCUTTA INSTITUTE OF West -

Durgapur Women's College--Self Study Report

Durgapur Women’s College—Self Study Report 1 Durgapur Women’s College—Self Study Report 2 Durgapur Women’s College—Self Study Report List of Contents Page No. Preface 05 PART: A 08-31 Executive Summary 09 SWOC Analysis 18 Profile of the Institution 20 PART: B 32-172 Criteria- wise inputs Criterion I: Curricular Aspects 33 Criterion II: Teaching-Learning and Evaluation 63 Criterion III: Research, Consultancy and Extension 94 Criterion IV: Infrastructure and Learning Resources 115 Criterion V: Student Support and Progression 131 Criterion VI: Governance, Leadership and Management 150 Criterion VII: Innovation and Best Practices 168 PART: C 173-307 Evaluative Report of the Departments I: Bengali 174 II: Economics 187 III: English 203 IV: Hindi 216 V: History 222 VI: Philosophy 231 VII:Political Science 237 VIII:Sanskrit 244 IX: Chemistry 251 X: Computer Science 260 XI: Electronics 276 XII: Mathematics 288 XIII:Physics 294 PART: D 308-318 Annexure -- I : Copy of Layout of the College 309 Annexure – II: Letter of Declaration 312 Annexure -- III: Certificate of Compliance 313 Annexure—IV: Copy of UGC 2(f) 12(b) Certificates 314 Annexure—V: Copy of Cerificate of Affiliation:University of Burdwan 315 3 Durgapur Women’s College—Self Study Report Anneexure:VI: Copy of Certificate of Affiliation Kazi Nazrul Univeristy317 Annexure—VII: Copy of Audit Reports 318 4 Durgapur Women’s College—Self Study Report PREFACE " যাহা কিছু জাকিবার যযাগ্য তাহাই কবদ্যা , তাহা পু쇁ষকিও জাকিকত হইকব ,যেকেকিও জাকিকত হইকব —�ধু িাকজ খাটাইবার জিয যয তাহা িে , জাকিবার জিযই ‖ —-রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকু র ―স্ত্রীশিক্ষা ‖ Whatever is worthy to be known constitutes knowledge. -

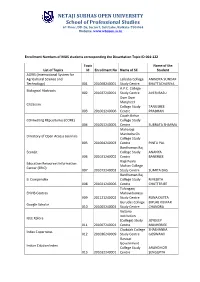

NETAJI SUBHAS OPEN UNIVERSITY School of Professional Studies 6Th Floor, DD-26, Sector I, Salt Lake, Kolkata-700 064 Website

NETAJI SUBHAS OPEN UNIVERSITY School of Professional Studies 6th Floor, DD-26, Sector I, Salt Lake, Kolkata-700 064 Website: www.wbnsou.ac.in Enrollment Numbers of MLIS students corresponding the Dissertation Topic ID 001-122 Topic Name of the List of Topics Id Enrollment No Name of SC Student AGRIS (International System for Agricultural Science and Lalbaba College ANINDYA SUNDAR Technology) 001 201068240001 Study Centre BHATTACHARJYA A.P.C. College Biological Abstracts 002 201027240001 Study Centre AVERI BASU Dum Dum Motijheel CiteSeerx College Study TANUSREE 003 201001240006 Centre PRADHAN Cooch Behar COnnecting REpositories (CORE) College Study 004 201053240005 Centre SUBRATA SHARMA Maharaja Manindra Ch. Directory of Open Access Journals College Study 005 201004240003 Centre PINTU PAL Bardhaman Raj EconLit College Study ANANYA 006 201021240002 Centre BANERJEE Raja Peary Education Resources Information Mohan College Center (ERIC) 007 201073240003 Study Centre SUMITA DAS Bardhaman Raj Ei Compendex College Study NIVEDITA 008 201021240006 Centre CHATTERJEE Tufanganj ENVIS Centres Mahavidyalaya 009 201121240002 Study Centre RUNA DUTTA Gurudas College BIPLAB KUMAR Google Scholar 010 201003240002 Study Centre CHANDRA Victoria Institution IEEE Xplore (College) Study JOYDEEP 011 201007240001 Centre MUKHERJEE Chakdah College SHASHANKA Index Copernicus 012 201036240009 Study Centre GOSWAMI Barasat Government Indian Citation Index College Study ARUNDHOTI 013 201032240001 Centre SENGUPTA NETAJI SUBHAS OPEN UNIVERSITY School of Professional Studies 6th Floor, DD-26, Sector I, Salt Lake, Kolkata-700 064 Website: www.wbnsou.ac.in Tamralipta Inspec Mahavidyalaya 014 201014240002 Study Centre SUKLA ROY Bardhaman Raj Internet Archive College Study 015 201021240007 Centre PAPAN GHOSH Dum Dum Motijheel J-Gate College Study AISHWARYYA 016 201001240002 Centre SAHA Raja N.L.