L2 Inflectional Morphology and Prosody: the Case of L1 Bengali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution, Optimization, and Language Change: the Case of Bengali Verb Inflections

Evolution, Optimization, and Language Change: The Case of Bengali Verb Inflections Monojit Choudhury1, Vaibhav Jalan2, Sudeshna Sarkar1, Anupam Basu1 1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, India {monojit,sudeshna,anupam}@cse.iitkgp.ernet.in 2 Department of Computer Engineering Malaviya National Institute of Technology, Jaipur, India [email protected] Abstract (e.g., Hare and Elman (1995); Dras et al. (2003); Ke et al. (2003); Choudhury et al. (2006b)), all the The verb inflections of Bengali underwent mathematical and computational models developed a series of phonological change between for explaining language change are built for artifi- 10th and 18th centuries, which gave rise cial toy languages. This has led several researchers to several modern dialects of the language. to cast a doubt on the validity of the current compu- In this paper, we offer a functional ex- tational models as well as the general applicability planation for this change by quantifying of computational techniques in diachronic explana- the functional pressures of ease of artic- tions (Hauser et al., 2002; Poibeau, 2006). ulation, perceptual contrast and learnabil- In this paper, we offer a functional explanation1 ity through objective functions or con- of a real world language change – the morpho- straints, or both. The multi-objective and phonological change affecting the Bengali verb multi-constraint optimization problem has inflections (BVI). We model the problem as a been solved through genetic algorithm, multi-objective and multi-constraint optimization whereby we have observed the emergence and solve the same using Multi-Objective Genetic of Pareto-optimal dialects in the system Algorithm2 (MOGA). -

An Alternative Account of English Consonant Cluster Adaptations in Bengali Dialects*

https://doi.org/10.24303/lakdoi.2019.27.3.99 An Alternative Account of English Consonant Cluster Adaptations in Bengali Dialects* Chin-Wan Chung (Chonbuk National University) Chung, Chin-Wan. (2019). An alternative account of English consonant cluster adaptations in Bengali dialects. The Linguistic Association of Korea Journal, 27(3), 99-123. This study provides a constraint-based analysis of cluster adaptations occurring in Bengali dialects such as spoken Bengali, Dhaka, and Sylheti when English complex words are realized by Bengali speakers or borrowed into Bengali. In spoken Bengali, speakers only employ epenthetic strategy when they realize onset clusters of English. For the selection of vowels, the neutral vowel of English is generally inserted between consonants but the high front vowel is prothesized when a cluster is composed of /s/ plus a voiceless stop. In Dhaka dialect, coda clusters are fixed by either insertion or deletion. Unlike spoken Bengali, the inserted vowel between sonorant consonants is affected by a neighboring vowel. Deletion of an obstruent normally occurs when a cluster consists of a sonorant plus an obstruent but an obstruent survives if a sonorant is dental liquid /r/ in Dhaka. Onset cluster adaptations in Sylheti is similar to that of spoken Bengali but one difference between the two dialects is that an interconsonantally inserted vowel is affected by a following vowel in Sylheti while spoken Bengali still maintains the quality of a neutral vowel. (Chonbuk National University) Key Words: consonant clusters, adaptations, insertion, deletion, repair strategy 1. Introduction * This research was supported by “Research Base Construction Fund Support Program” funded by Chonbuk National University in 2019. -

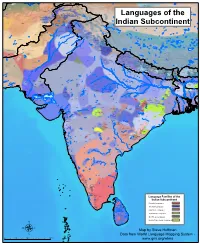

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Language Distinctiveness*

RAI – data on language distinctiveness RAI data Language distinctiveness* Country profiles *This document provides data production information for the RAI-Rokkan dataset. Last edited on October 7, 2020 Compiled by Gary Marks with research assistance by Noah Dasanaike Citation: Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks (2016). Community, Scale and Regional Governance: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Vol. II. Oxford: OUP. Sarah Shair-Rosenfield, Arjan H. Schakel, Sara Niedzwiecki, Gary Marks, Liesbet Hooghe, Sandra Chapman-Osterkatz (2021). “Language difference and Regional Authority.” Regional and Federal Studies, Vol. 31. DOI: 10.1080/13597566.2020.1831476 Introduction ....................................................................................................................6 Albania ............................................................................................................................7 Argentina ...................................................................................................................... 10 Australia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Austria .......................................................................................................................... 14 Bahamas ....................................................................................................................... 16 Bangladesh .................................................................................................................. -

Languages of India Being a Reprint of Chapter on Languages

THE LANGUAGES OF INDIA BEING A :aEPRINT OF THE CHAPTER ON LANGUAGES CONTRIBUTED BY GEORGE ABRAHAM GRIERSON, C.I.E., PH.D., D.LITT., IllS MAJESTY'S INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE, TO THE REPORT ON THE OENSUS OF INDIA, 1901, TOGETHER WITH THE CENSUS- STATISTIOS OF LANGUAGE. CALCUTTA: OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, INDIA. 1903. CALcuttA: GOVERNMENT OF INDIA. CENTRAL PRINTING OFFICE, ~JNGS STRERT. CONTENTS. ... -INTRODUCTION . • Present Knowledge • 1 ~ The Linguistio Survey 1 Number of Languages spoken ~. 1 Ethnology and Philology 2 Tribal dialects • • • 3 Identification and Nomenolature of Indian Languages • 3 General ammgemont of Chapter • 4 THE MALAYa-POLYNESIAN FAMILY. THE MALAY GROUP. Selung 4 NicobaresB 5 THE INDO-CHINESE FAMILY. Early investigations 5 Latest investigations 5 Principles of classification 5 Original home . 6 Mon-Khmers 6 Tibeto-Burmans 7 Two main branches 7 'fibeto-Himalayan Branch 7 Assam-Burmese Branch. Its probable lines of migration 7 Siamese-Chinese 7 Karen 7 Chinese 7 Tai • 7 Summary 8 General characteristics of the Indo-Chinese languages 8 Isolating languages 8 Agglutinating languages 9 Inflecting languages ~ Expression of abstract and concrete ideas 9 Tones 10 Order of words • 11 THE MON-KHME& SUB-FAMILY. In Further India 11 In A.ssam 11 In Burma 11 Connection with Munds, Nicobar, and !lalacca languages 12 Connection with Australia • 12 Palaung a Mon- Khmer dialect 12 Mon. 12 Palaung-Wa group 12 Khaasi 12 B2 ii CONTENTS THE TIllETO-BuRMAN SUll-FAMILY_ < PAG. Tibeto-Himalayan and Assam-Burmese branches 13 North Assam branch 13 ~. Mutual relationship of the three branches 13 Tibeto-H imalayan BTanch. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Pashto, Southern Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Shughni Chinese, Mandarin Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Wakhi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Khowar Khowar Domaaki Khowar Kati Shina Farsi, Eastern Yidgha Munji Kati Kalasha Gujari Kati KatiPhalura Gujari Kalami Shina, Kohistani Gawar-BatiKamviri Kalami Dameli TorwaliKohistani, Indus Gujari Chilisso Pashayi, Northwest Prasuni Kamviri Balti Kati Ushojo Gowro Languages of the Gawar-Bati Waigali Savi Chilisso Ladakhi Ladakhi Bateri Pashayi, SouthwestAshkun Tregami Pashayi, Northeast Shina Purik Grangali Shina Brokskat ParyaPashayi, Southeast Aimaq Shumashti Hindko, Northern Hazaragi GujariKashmiri Pashto, Northern Purik Tirahi Ladakhi Changthang Kashmiri Gujari Indian Subcontinent Gujari Pahari-PotwariGujari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Hindko, Southern Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Ormuri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Dogri-Kangri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Pashto, Southern Ladakhi Pashto, Central Khams Pahari, Kullu Kinnauri, Bhoti KinnauriSunam Gahri Shumcho Panjabi, Western Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Kinnauri, Chitkuli Pahari, Mahasu Panjabi, Eastern Panang Jaunsari Garhwali Balochi, Western Pashto, Southern Khetrani Tehri Rawat Tibetan Hazaragi Waneci Rawat Brahui Saraiki DarmiyaByangsi Chaudangsi Tibetan Balochi, Western Chaudangsi Bagri Kumauni Humla Bhotia Rangkas Dehwari Mugu Kumauni Tichurong Dolpo Haryanvi Urdu Buksa Lopa Nepali Kaike Panchgaunle Balochi, Eastern Raute Tichurong Sholaga Baragaunle Raji Nar Phu Tharu, Rana Sonha Thakali Kham, GamaleKham, Sheshi -

Bengali Language Handbook

R E- F 0 R T RESUMES ED 012 911 48 AL 000 604 BENGALI LANGUAGE HANDBOOK. BY- RAY, FUNYA SLOKA AND. OTHERS CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, WASHINGTON, D.C. REPORT NUMBER BR-5 -1242 PUB DATE 66' CONTRACT OEC -2 -14 -042 EDRS PRICE MF$0.75 HC-$6.04 15IF. DESCRIPTORS-*BENGALI, *REFERENCE BOOKS, LITERATURE GUIDES, CONTRASTIVE LINGUISTICS, GRAMMAR, PHONETICS, CULTURAL BACKGROUND, SOCIOLINGUISTICS, WRITING, ALPHABETS, DIALECT STUDIES, CHALIT, SADHU, INDIA, WEST BENGAL, EAST PAKISTAN, THIS VOLUME OF THE LANGUAGE HANDBOOK SERIES IS INTENDED TO SERVE AS AN OUTLINE OF THE SALIENT FEATURES OF THE BENGALI LANGUAGE SPOKEN BY OVER 80 MILLION PEOPLE IN EAST PAKISTAN AND INDIA. IT WAS WRITTEN WITH SEVERAL READERS IN MIND-.-(1) A -LINGUIST INTERESTED IN BENGALI BUT NOT HIMSELF A SPECIALIST INTHE LANGUAGE,(2) AN INTERMEDIATE OR ADVANCED STUDENT WHO WANTS A CONCISE'GENERAL PICTURE OF THELANGUAGE AND ITS SETTING, AND (3) AN AREA SPECIALIST WHO NEEDS BASIC LINGUISTIC OR SOCIOLINGUISTIC FACTS ABOUT THE AREA. CHAPTERS ON THE LANGUAGE SITUATION, PHONOLOGY, AND ORTHOGRAPHY. PRECEDE THE LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX. ALTHOUGH THE LINGUISTIC DESCRIPTION IS NOT INTENDED TO BE DEFINITIVE, IT USES TECHNICAL TERMINOLOGY AND ASSUMES THE READER HAS PREVIOUS KNOWLEDGE OF LINGUISTICS. STRUCTURAL DIFFERENCES 'BETWEEN BENGALI AND AMERICAN ENGLISH ARE DISCUSSED AS ARE THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SADHU STANDARD AND CHALIT STANDARD BENGALI. THE DACCA DIALECT AND THE CHITTAGONG DIALECT ARE BRIEFLY TREATED AND THEIR GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION IS SHOWN ON A MAP OF BENGALI DIALECTS. FINAL CHAPTERS SURVEY THE . HISTORY OF BENGALI LITERATURE, SCIENCE, AND LITERARY CRITICISM. THIS HANDBOOK IS ALSO AVAILABLE FOR $3.00 FROM THE CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, 1717 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, WW., WASHINGTON, D.C., 20036. -

The Concept of Language Is As Old As the Human Itself. According to The

Grassroots Vol. 49, No.I January-June 2015 LANGUAGE AND DIALECT: CRITERIA AND HISTORICAL EVIDENCE María Isabel Maldonado García Akhtar Hussain Sandhu ABSTRACT History is replete with events, change, cause and effect on the basis of language. Political movements and geographical changes occurred in different corners of the world and eras have slightly and massively been linked with language. Many regions are currently facing separatist movements mainly rooted in languages or dialects. A few authors have written about the criteria for defining a particular linguistic system as a language in terms of the number of speakers, its prestige, whether they have been accepted as national languages, whether they present written forms and literary traditions, whether similar linguistic systems exist in the same country or area which present an elevated level of lexical similarity, whether they have less number of speakers, etc. It seems simple to differentiate between a language and a dialect. However, although the definition of language seems to be clear and every dictionary of the world contains it, in practical terms when facing the dilemma of whether a particular linguistic system is a language or a dialect, these definitions are blurry from a scientific point of view and sociolinguistic and political pressures may play a role in many cases. This paper will propose better criteria towards differentiation of language and dialect basing the argument on the empirical evidence of the history of linguistics. _________________________ Keywords: Language, dialect, Sindhi, Bengali, Punjabi, Saraiki, language varieties, difference between language and dialect. DEFINITIONS OF LANGUAGE AND DIALECT The concept of language is as old as the human itself. -

The History of the Bengali Language

THE HISTORY OF THE BENGALI LANGUAGE THE HISTORY OF THE BENGALI LANGUAGE BY BIJAYCHANDRA MAZUMDAR, LBCTUBEB IN THF; DEPARTMENTS OF COMPARATIVE PHILOLOGY, ANTHROPOLOGY AND INDIAN VERNACULARS, CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA 19:20 PRINTED BY ATULCHANDRA BHATTACHARYYA AT THE CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY PRESS, SENATE HOUSE, CALCUTTA PREFACE The following lectures on the History of the Bengali Language are intended to give a sketch, in broad outline, of the origins of that language and the various influences, linguistic, ethnic, social, that shaped and moulded its earlier history. One essential requirement of a scientific procedure of this I in an investigation sort, have steadily kept in view. The ethnic as well as the social history of a people or group of peoples must corroborate and light up the linguistic history, if the latter is to be rescued from the realm of prehistoric romance to which the story of philo- logical origins, as so often told, must be however reluctantly assigned by the critical or scientific historian of to-day. One or two incidental results of my application of this anthropological test may be here mentioned. I have had no occasion to invent different Aryan belts for the imaginary migratory movements of some unknowable patois-speaking hordes, to account for the distinctive and peculiar pheno- mena of the provincial languages or dialects, e.g., those of Bengal : they are fitly explained by the successive ethnic contacts and mixtures with neighbouring or surrounding indigenous peoples. Similarly I have had no hesitation in recognizing within proper limits, the principle of miscege- nation in the growth of language, as of race, provided that the organic accretions from outside grow to the living radicle or nucleus which persists as an independent or individual entity. -

Bengali (Bangladeshi Standard)

Journal of the International Phonetic Association http://journals.cambridge.org/IPA Additional services for Journal of the International Phonetic Association: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Bengali (Bangladeshi Standard) Sameer ud Dowla Khan Journal of the International Phonetic Association / Volume 40 / Issue 02 / August 2010, pp 221 - 225 DOI: 10.1017/S0025100310000071, Published online: 08 July 2010 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0025100310000071 How to cite this article: Sameer ud Dowla Khan (2010). Bengali (Bangladeshi Standard). Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 40, pp 221-225 doi:10.1017/S0025100310000071 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/IPA, IP address: 134.10.6.46 on 10 Feb 2014 ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE IPA Bengali (Bangladeshi Standard) Sameer ud Dowla Khan Department of Linguistics, UCLA [email protected] Bengali ( /baNla/) is an Indo-European language (Indic branch) spoken by over 175 million people in Bangladesh and eastern India (Dasgupta 2003: 352; Lewis 2009). The speech illustrated below is representative of the standard variety widely spoken in Dhaka and other urban areas of Bangladesh. Consonants Plosives and affricates contrast in voicing and aspiration. Although displayed in one column, the articulation of the postalveolars varies by consonant type (see ‘Conventions’ below). Barring rare exceptions, /d h/ do not occur word-finally and /N/ does not occur word-initially (Dasgupta 2003: 358–359). Journal of the International Phonetic Association (2010) 40/2 C International Phonetic Association doi:10.1017/S0025100310000071 222 Journal of the International Phonetic Association: Illustrations of the IPA Vowels Vowels are plotted below based on F1 and F2 frequencies averaged across six speakers. -

Adjectives in Bengali Language a Dissertation Submitted to The

Adjectives in Bengali Language A dissertation submitted to the Department of Linguistics, Assam University, and Silchar as a part of academic requirements for the fulfilment of Master in Arts Degree in Linguistics From Assam University 2020 Roll- 042018No-2083100011 Registration No.-20180016659 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS Rabindranath Tagore School of Indian Languages and Cultural Studies ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION: 2020 1 .CERTIFICATE Certified that the dissertation project entitled Adjectives in Bengali Language is submitted by Roll:......042018.....No:....2083100011..........,Registration No.....20180016659.......... as part of academic requirements for the fulfilment of Master in Arts Degree in Linguistics. This work has not been submitted previously by anyone for fulfilment the requirements of Master of Arts Degree in Linguistics in Assam University,Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University. I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of Award of the Degree from this University. 5.10.20 Name & Signature of Supervisor (Signature) Dr.ParamitaPurkait Assistant Professor Department of Linguistics 2 Assam University, Silchar DECLARATION I bearing Roll- ..042018....No-…2083100011… Registration No.......20180016659..............- hereby declare that the content of the dissertation entitled Adjectives in Bengali Language is a genuine and the result of my work. The content of this work has not been submitted in part or whole, to any institution, including this University, for any Degree or Diploma. The dissertation is being submitted to the Department of Linguistics, Assam University as a part of academic requirements for the fulfilment of Master in Arts Degree in Linguistics. -

Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization

Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization Andras´ Kornai, Pushpak Bhattacharyya Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Department of Algebra Indian Institute of Technology, Budapest Institute of Technology [email protected], [email protected] Abstract We describe the planned Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization (ISLV) project, which aims at turning as many languages and dialects of the subcontinent into digitally viable languages as feasible. Keywords: digital vitality, language vitalization, Indian subcontinent In this position paper we describe the planned Indian Sub- gesting that efforts aimed at building language technology continent Language Vitalization (ISLV) project. In Sec- (see Section 4) are best concentrated on the less vital (but tion 1 we provide the rationale why such a project is called still vital or at the very least borderline) cases at the ex- for and some background on the language situation on the pense of the obviously moribund ones. To find this border- subcontinent. Sections 2-5 describe the main phases of the line we need to distinguish the heritage class of languages, planned project: Survey, Triage, Build, and Apply, offering typically understood only by priests and scholars, from the some preliminary estimates of the difficulties at each phase. still class, which is understood by native speakers from all walks of life. For heritage language like Sanskrit consider- 1. Background able digital resources already exist, both in terms of online The linguistic diversity of the Indian Subcontinent is available material (in translations as well as in the origi- remarkable, and in what follows we include here not nal) and in terms of lexicographical and grammatical re- just the Indo-Aryan family, but all other families like sources of which we single out the Koln¨ Sanskrit Lexicon Dravidian and individual languages spoken in the broad at http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/monier and the geographic area, ranging from Kannada and Telugu INRIA Sanskrit Heritage site at http://sanskrit.inria.fr.