Facilitating Group Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

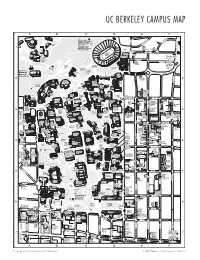

Uc Berkeley Campus

University of Mediterranean California Botanical Garden of Human Garden Asian Old Roses Genome Southern Australasian South 84 Laboratory African New American World Rd vin 74 Desert Chinese al C Herb Medicinal 86 83 Garden Herb Cycad & Garden Palm 85 Garden 85B Miocene Eastern Mexican/ Forest North Central American P Strawberry American a Californian n Entrance o Mather r a Silver Redwood m Space Grove ic Sciences P la c Laboratory e L e Mathematical Molecular e Dr Sciences nial Foundry R ten National d 73 Research en Institute C Center for Electron Microscopy 66 72 67 62 Grizzly 77A Peak Entrance y 77 31 a W 69 ic m a Hill r o Terrace n Parking Lawrence a Lots P 75A Berkeley Claremont 75 75B National D Canyon w G Regional i Laboratory y g l a Strawberry a s h Preserve W t e Canyon P 79 r t l R Center h a d Haas ce Lawrence 78 76 Clubhouse ig Hall of C w e D Science n t 76 e Strawberry n n Canyon i a Recreational l Vista 26 D Area r Parking Lot Sand Volleyball 3024 Court #1Tanglewood Rd 25 J H 48 20 G Track/ Faculty 5 4 Soccer 45 Levine-Fricke Smyth- Field Archives Apartments Field F Fernwald 21 16 14 d 52 R Family en y 3001 d e rd Wa E Housing Segré R c A P ic n anoram 3001 e r y st Derby 17 27 53 7 a a wa 19 w UC BERKELEY CAMPFeUrnwald SRd MAPGolden 22 E y D a M W d C Bear r R L o c n a i la Recreation il n s Witter M 37 m c y s Community Center Golden M Advanced o w a Field Witter A r n rd e 71 Light o n Rd o Center 25 Bear 58 Parking Field R o n Redwood 47 Source Lot d d a Smyth Pool BBQ P 6 R House Area Gardens d 46 15 s Sports Ln -

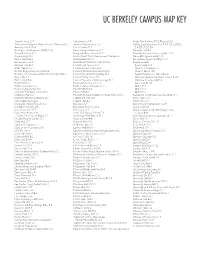

Uc Berkeley Campus Map Key

UC BERKELEY CAMPUS MAP KEY Alumni House, D-5 Greenhouse, A-7 Pacific Film Archive (PFA) Theater, D-4 Andersen Auditorium (Haas School of Business), C-2 Grinnell Natural Area, C-6 Parking Lots/Structures, A-3, A-4/5, D-3, D/E-6, Anthony Hall, C/D-4 Haas Pavilion, D-5 E-4, E/F-3, E/F-5/6 Architects and Engineers (A&E), D-4 Haas School of Business, C-2 Pimentel Hall, B-3 Bancroft Library, C-4 Hargrove Music Library, D-3 Pitzer Auditorium (Latimer Hall), C-2/3 Banway Bldg., D-7 Haste Street Child Development Center, F-5 Police, UC (Sproul Hall), D-4 Barker Hall, A/B-6 Haviland Hall, B-4/5 Recreational Sports Facility, D-5/6 Barrow Lane, D-4 Hazardous Materials Facility, C/D-6 Residence Halls Barrows Hall, D-4 Hearst Field Annex, D-4 Bowles Hall, C-2 BART Station, C-7 Hearst Greek Theatre, B-2 Clark Kerr Campus, F-1 Bechtel Engineering Center, B-3/4 Hearst Memorial Gymnasium, D-3 Cleary Hall, E/F-4/5 Berkeley Art Museum (Woo Hon Fai Hall), D/E-3 Hearst Memorial Mining Bldg., B-3 Foothill Residence Halls, A/B-2/3 Birge Hall, C-3 Hearst Mining Circle, B-3 Ida Louise Jackson Graduate House, E-2/3 Blum Hall, A/B-4 Hearst Museum of Anthropology, D-3 Martinez Commons E/F-4 Boalt Hall, D-2 Heating Plant, Central, C-6 Stern Hall, B-2/3 Botanical Garden, C-1 Hellman Tennis Complex, C-6 Unit 1, E-3 Brain Imaging Center, B-5 Hertz Hall, C/D-3 Unit 2, F-3 C.V. -

Britten & Bernstein

Berkeley_Program Covers.pdf 2 9/18/18 6:49 PM SYMPHONIC II BRITTEN & BERNSTEIN 01.31.19 | 8:00 PM ZELLERBACH HALL BENJAMIN BRITTEN Four Sea Interludes from Peter Grimes HANNAH KENDALL Disillusioned Dreamer: (World Premiere) LEONARD BERNSTEIN Symphony No. 2 for Piano and Orchestra, The Age of Anxiety Jonathon Heyward Guest Conductor Andrew Tyson Piano 18/19 Berkeley Symphony 18/19 Season 5 Message from the Board President 7 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director 9 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 11 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 17 Berkeley Sounds Composer Fellows 21 Tonight’s Program 25 Program Notes 41 Conductor Jonathon Heyward 43 Guest Artist & Composer 47 Berkeley Symphony Salutes Rose Marie Ginsburg 49 About Berkeley Symphony 52 Music in the Schools 55 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 57 Annual Membership Support 64 Broadcast Dates 69 Contact 70 Ad Index: Support Businesses That Support Us Media Sponsor SEASON SPONSORS Official Wine Gertrude Allen • Laura & Paul Bennett • Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Sponsor Getty • Jill Grossman • Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson • Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Rose Ray & Robert Kroll • Tricia Swift • S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James • Anonymous Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. January 31, 2019 3 4 January 31, 2019 Message from the Board President elcome to the second concert in WBerkeley Symphony’s 2018/19 Season. -

ACCOUNTABILITY PROFILE University of California, Berkeley

ACCOUNTABILITY PROFILE University of California, Berkeley California’s Investment in Berkeley GRAND ASPIRATIONS built this university more than 140 years ago when Berkeley, the flagship institution of the University of California system, was established. The goal was to create an institution with attributes “equal to those of Eastern Colleges,” what today are called the Ivy League schools. This new university not only would educate students but also serve and assist the people of California. As a public research university, Berkeley was charged with seeking new knowledge and discovery to serve the public interest, and providing Californians access to its excellent educational opportunities. Public research universities are pivotal in realizing society’s potential for opportunity, innovation, social justice, and prosperity — extending the public good for the benefit of all. Today, Berkeley is recognized as a leader among the world’s universities in offering true breadth, access, and comprehensive excellence. As UC’s oldest campus, Berkeley is home to many historic sites, including South Hall [the first UC building, constructed in 1873], Hearst Greek Theatre [1903], California Hall [1905], Hearst Memorial Mining Building [1907], the Campanile [1914], Doe Library [1917], and Wheeler Hall [1917]. The campus has many world- class research museums, field stations, and other research centers, along with a library collection that ranks as one of the “Berkeley — the university — seems to best in the nation. In 2007 the Association of Research Libraries ranked me, more and more, to be California’s Berkeley’s library among the top five university research libraries in North America. Its rare and specialized collections, such as the Bancroft Library’s highest, most articulate idea of itself.” Mark Twain Papers and Project [the world’s largest collection of Twain — JOAN DIDION ’56 materials], serve educators and scholars from around the state and the Author world. -

Campus Parking Map

Campus Parking Map 1 2 3 4 5 University of Mediterranean California Botanical Garden of PARKING DESIGNATION Human Garden Asian Old Roses Bicycle Dismount Zone Genome Southern Australasian South 84 Laboratory Julia African American (M-F 8am-6pm) Morgan New World Central Campus permit Rd Hall C vin Desert al 74 C Herb Campus building 86 83 Garden F Faculty/staff permit Cycad & Chinese Palm Medicinal Garden Herb Construction area 85 Garden S Student permit Miocene Eastern Mexican/ 85B Central Forest North P Botanical American American a Visitor Information n Disabled (DP) parking Strawberry Garden o Botanical r Entrance Lot Mather Californian a Redwood Garden m Entrance ic Grove Emergency Phone P Public Parking (fee required)** A l l P A i a SSL F P H V a c r No coins needed - Dial 9-911 or 911e Lower T F H e Lot L r Gaus e i M Motorcycle permit s W F a Mathematical r Molecular e y SSL H ial D R n Campus parking lot Sciences nn Foundry d a Upper te National 73 d en r Research C o RH Lot Center for J Residence Hall permit Institute r Electron Lo ire Tra e Permit parking street F i w n l p Microscopy er 66 Jorda p 67 U R Restricted 72 3 Garage entrance 62 MSRI P H Hill Area permit Parking 3 Garage level designation Only Grizzly 3 77A rrace Peak CP Carpool parking permit (reserved until 10 am) Te Entrance Coffer V Dam One way street C 31 y H F 2 Hill 77 Lot a P ce W rra Terrace CS Te c CarShare Parking 69 i Streetm Barrier V e 1 a P rrac Lots r Te o n a V Visitor Parking on-campus P V Lawrence P East Bicycle Parking - Central Campus Lot 75A -

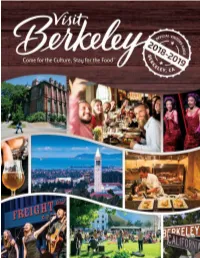

Visit-Berkeley-Official-Visitors-Guide

Contents 3 Welcome 4 Be a Little Berkeley 6 Accommodations 16 Restaurants 30 Local Libations 40 Arts & Culture 46 Things to Do 52 Shopping Districts 64 #VisitBerkeley 66 Outdoor Adventures & Sports 68 Berkeley Marina 70 Architecture 72 Meetings & Celebrations 76 UC Berkeley 78 Travel Information 80 Transportation 81 Visitor & Community Services 82 Maps visitberkeley.com BERKELEY WELCOMES YOU! The 2018/19 Official Berkeley Visitors Guide is published by: Hello, Visit Berkeley, 2030 Addison St., Suite #102, Berkeley, CA 94704 (510) 549-7040 • www.visitberkeley.com Berkeley is an iconic American city, richly diverse with a vibrant economy inspired in EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE great measure by our progressive environ- Greg Mauldin, Chairman of the Board;General Manager, Hotel Shattuck Plaza Vice Chair, (TBA); mental and social policies. We are internationally recognized for our arts Thomas Burcham, Esq., Secretary/Treasurer; Worldwide Farmers and culinary scenes, as well as serving as home to the top public univer- Barbara Hillman, President & CEO, Visit Berkeley sity in the country – the University of California, Berkeley. UC Berkeley BOARD OF DIRECTORS is the heart of our city, and our neighborhood districts surround the Cal John Pimentel, Account Exec/Special Projects, Hornblower Cruises & Events campus with acclaimed restaurants, great independent shops and galleries, Lisa Bullwinkel, Owner; Another Bullwinkel Show world-class performing arts venues, and wonderful parks. Tracy Dean, Owner; Design Site Hal Leonard, General Manager; DoubleTree by Hilton Berkeley Marina I encourage you to discover Berkeley’s signature elements, events and Matthew Mooney, General Manager, La Quinta Inn & Suites LaDawn Duvall, Executive Director, Visitor & Parent Services UC Berkeley engaging vibe during your stay with us. -

Clyne & Strauss

Berkeley_Program Covers.pdf 4 9/18/18 6:49 PM SYMPHONIC IV CLYNE & STRAUSS 05.02.19 | 8:00 PM ZELLERBACH HALL RICHARD WAGNER Overture to Tannhäuser ANNA CLYNE This Midnight Hour THOMAS ADÈS Dances from Powder Her Face RICHARD STRAUSS Rosenkavalier Suite Christian Reif Guest Conductor ODC/DANCE 18/19 Berkeley Symphony 18/19 Season 5 Message from the Board President 7 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director 9 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 11 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 17 Berkeley Sounds Composer Fellows 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 41 Conductor Christian Reif 43 Guest Artists 47 About Berkeley Symphony 50 Music in the Schools 55 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 57 Annual Membership Support 64 Broadcast Dates 69 Contact 70 Ad Index: Support Businesses That Support Us Media Sponsor SEASON SPONSORS Official Wine Gertrude Allen • Laura & Paul Bennett • Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Sponsor Getty • Jill Grossman • Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson • Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Rose Ray & Robert Kroll • Tricia Swift • S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James • Anonymous Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. May 2, 2019 3 4 May 2, 2019 Message from the Board President s we celebrate the final concert of the 2018/19 ASeason with Symphonic IV: Clyne & Strauss, we have some celebratory changes coming to the future of Berkeley Symphony. -

Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory

. -\\i ''-' \ \' "r.., (' /' ·,I ,,;1, '\ ), I I I_,,,, --- :::0 I'T1 () "T'I ..... c I'T1 , o· :::o ororrr t:__. VI z () k Ill z I'T1 '/' r+O (J) r+ () 0 "'C ......OJ -< 0.--- 10 \• "'C () c 0 OJ "C I cc:: ........ N •"'I ........ .) ~0 •/ .• \ ,---- /I' ',, 1'',' I ,, ''' DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. PUB-727 CoMMUNITY RELATIONS PLAN for Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory Environmental Restoration Program \, ' ' Prepared by: ICF Kaiser Engineers July 1993 '' (\( *re<y<:leclpoper This work was done at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, which is operated for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract #DE-AC03-76SF00098. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms ......................................... -

Resource Guide for Parents

RESOURCE GUIDE FOR PARENTS CalParents elena zhukova RESOURCE GUIDE FOR PARENTS GETTING INVOLVED 4 STAYING CONNECTED 7 ACADEMICS 10 STUDENT HEALTH 17 CAMPUS SAFETY 19 STUDENT LIFE 22 RESOURCES 28 elena zhukova WELCOME TO BERKELEY Dear Cal Parents: UC Berkeley is a place of immense intellectual vitality, where some of today’s brightest students and scholars work together to deepen understanding of the world we live in. It is also a place that is steadfastly committed to widening the doors to educational opportunity, a place that sets young people from all backgrounds on a path towards success in their lives and in their careers. This combination of excellence and access is what defines and animates us; it is truly Berkeley’s DNA. I arrived at Berkeley in 1970 as a freshly minted PhD who had never been west of Philadelphia, and this institution transformed me – just as it continues to transform so many of those who study here, work here, visit, and otherwise come into contact with our campus. I know that Berkeley will prove just as transformative for your sons and daughters. This resource guide provides a wealth of information about UC Berkeley, and can serve as a starting point for any questions you might have about our campus. We also invite you to call on Cal Parents at any time if you need additional assistance. On behalf of the entire UC Berkeley community: Welcome to our family, and Go Bears! CAROL CHRIST Chancellor It is with great honor that we welcome you to the Cal family! We are excited that your student has chosen to study at the University of California, Berkeley. -

San Francisco Airport

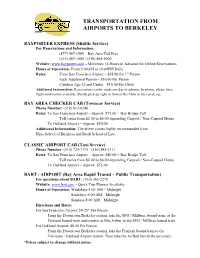

TRANSPORTATION FROM AIRPORTS TO BERKELEY BAYPORTER EXPRESS (Shuttle Service) For Reservations and Information: (877) 467-1800 – Bay Area Toll Free (415) 467-1800 / (510) 864-4000 Website: www.bayporter.com – Minimum 15-Hours in Advance for Online Reservations Hours of Operation: From 3:00AM to 10:00PM Daily Rates: From San Francisco Airport – $38.00 for 1st Person Each Additional Person – $10.00 Per Person Children Age 12 and Under – $10.00 Per Child Additional Information: Reservations can be made one day in advance by phone, please have flight information available. Shuttle pick-up right in front of the Club, in the cul-de sac. BAY AREA CHECKER CAB (Towncar Service) Phone Number: (510) 612-6546 Rates: To San Francisco Airport – Approx. $75.00 + Bay Bridge Toll Toll varies from $2.00 to $6.00 depending Carpool / Non-Carpool Hours To Oakland Airport – Approx. $50.00 Additional Information: The driver comes highly recommended from Haas School of Business and Boalt School of Law. CLASSIC AIRPORT CAB (Taxi Service) Phone Number: (510) 725-7175 / (510) 845-1111 Rates: To San Francisco Airport – Approx. $80.00 + Bay Bridge Toll Toll varies from $2.00 to $6.00 depending Carpool / Non-Carpool Hours To Oakland Airport – Approx. $52.00 BART / AIRPORT (Bay Area Rapid Transit – Public Transportation) For questions about BART: (510) 465-2278 Website: www.bart.gov – Quick Trip Planner Available Hours of Operation: Weekdays 4:00 AM – Midnight Saturdays 6:00 AM – Midnight Sundays 8:00 AM – Midnight Directions and Rates: For San Francisco Airport: $9.25* Per Person From the Downtown Berkeley station, take the SFO / Millbrae bound train, or the Fremont bound train and transfer at MacArthur to the SFO / Millbrae bound train. -

Clipping File Subject Headings

Call Number File Name Cabinet 1 Abortion Abortion Drugs AC Transit 1987-88 AC Transit 1989-94 AC Transit 1995-2000 AC Transit 2001-03 AC Transit 2004- Addresses-Literature Related Affirmative Action African American History Month African Americans AIDS and the Arts AIDS -1989 AIDS 1990-99 AIDS 2000- Air Pollution -1999 Air Pollution 2000- Airports Alameda County Supervisors Albany Bulb Alternative Services Coalition Animal Rights 1985-1987 Animal Rights 1988-92 Animal Rights 1993-99 Animal Rights 2000- Animals -1989 Animals 1990-99 Animals 2000- Antennas Anti-Apartheid Movement- U.C.B Anti-Apartheid Movement 1971-89 Anti-Apartheid Movement 1990- Appreciation of Excellence in Youth Program Arab Americans Architecture (General) Architecture-- Apartments Architecture-- Apartments-- Gaia Building Architecture-- BAHA-- (Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association) Architecture-- BAHA Calendars 1 of 2 Architecture-- BAHA Calendars 2 of 2 Architecture-- BAHA Walking Tours Archtiecture-- BAHA Newsletters Architecture-- Banks Architecture-- Berkeley City Club Architecture-- Biographis A-I Architecture-- Biographies J-Z Architecture-- Biographies-- Alexander, Christopher Architecture-- Biographies-- Babson, Seth Architecture-- Biographies-- Coxhead, Ernest Architecture-- Biographies-- Eckbo, Garrett Architecture-- Biographies-- Fernau, Richard Architecture-- Biographies-- Funk, John Architecture-- Biographies-- Greene, Charles & Henry (Greene & Greene) Architecture-- Biographies-- Gutterson, Henry Architecture-- Biographies-- Hall, Liola Architecture-- -

Berkeley Lab

LBNL/PUB-5518 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA BERKELEY LAB 2006 LONG RANGE DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD 4INTRODUCTION Laboratory Location 10 Berkeley Laboratory Historical Perspective 14 Berkeley Lab 2006 20 Facilities Conditions 24 BACKGROUND The Scientific Vision for Berkeley Lab 30 1 Space and Population Projections 34 The Site and Facilities Vision 38 ontents THE VISION C 1 Introduction to The Plan 44 2 Land Use 46 Development Framework 56 Vehicle Access, Circulation, and Parking 62 Pedestrian Circulation 70 Open Space and Landscape 74 Utilities and Infrastructure 82 THE PLAN Appendix A: Main Site Building Inventory 88 Appendix B: Land Leases 94 3 Appendix C: Figures and Tables 96 Appendix D: Related Documents 99 Appendix E: Abbreviations and Definitions 100 Appendix F: Berkeley Lab Organization 102 Appendix G: Acknowledgments 103 APPENDICES Appendix H: Index 104 1 Director’s Foreword ARD W LET ’S RENEW OUR COMMITMENT TO RESEARCH , EDUCATION , AND INNOVATION WHI L E SERVING AS A ORE F POSITIVE FORCE IN ECONOMIC , ENVIRONMENTA L , AND COMMUNITY RESPONSIBI L ITY . asic research such as the work performed at Berkeley As a leading institution in the areas of energy and environmen- Lab underpins our discoveries and, ultimately, the se- tal research, we are committed to developing the Laboratory curity, economic prosperity, and health of our citizens. in a manner that sets the standard for resource conservation director’s BACKGROUND B The Laboratory’s combination of strengths in rapidly advanc- and stewardship. To this end, the Berkeley Lab Sustainability 2 ing areas of science and unique research facilities enables the Policy was recently established to formalize our simultaneous development of large-scale, interdisciplinary research programs and balanced pursuit of economic viability, environmental to strengthen the foundations of America’s competitiveness.