MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

Trafalgar Day Dr Liz Sidwell Our Eco

This issue: Victory Open Evening | Sixth Form Trip | Council Visit |<U 3UR¿OHV November 2011 Vol 2 No 1 Trafalgar Day Celebrations Galore over 2 days Dr Liz Sidwell Full visit report Our Eco Day We show our true green colours www.ormistonvictoryacademy.co.uk November 2011 Victory Flag: Vol 1 No. 6 Principal Points P3 News in Brief P4 Costessey News/Beauty Blog P5 Celebrating Trafalgar Day P6 - 11 Reach For The Stars P12 - 13 Beauty Transformational A-Levels P14 Eton @ Norfolk P15 School Commissioner Visit P16 - 17 ISSUE Pen to Paper P18 VIP Roll Of Honour P19 Victory Goes Green P20 - 21 @Victory Green Academy Update P22 - 23 VIP Visit - Peter Swift P24 Lights, Camera, Action P25 7KH¿UVWEHDXW\VDORQZLWKLQDQ$FDGHP\ Welcome Year 6s Victory Open Evening P26 from across the county. It was a Victory In The Stars P27 Principal Points brilliant day. State of the art facilities, The Stars @ Victory P27 Sixth Form Sojourn Trip P28 - 29 So much has happened I said from the outset that my goal was Family Memories P30 WRPDNH9LFWRU\$FDGHP\WKHÀDJVKLS latest technologies in the last few months. school of the Eastern Region. By any Sixth Form Makeover P31 measure, we are well on the way to Open Thursday 1pm-4pm and Friday 9.30am – 2.30pm Inside Science P32 Our GCSE results were achieving this. Beauty @ Victory P33 We offer a full range of beauty treatments. Full price list available outstanding with a Above all, everything we do is for County Council Visit P34 Ring for appointments on 01603 742310 ex 3312 our students. -

Radio 4 Listings for 21 – 27 August 2021 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 21 AUGUST 2021 SAT 06:07 Open Country (M000ytzz) Jay Rayner Hosts the Culinary Panel Show

Radio 4 Listings for 21 – 27 August 2021 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 21 AUGUST 2021 SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000ytzz) Jay Rayner hosts the culinary panel show. Sophie Wright, Tim A Fabric Landscape Anderson, Asma Khan and Dr Annie Gray share delectable SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000yvbc) ideas and answer questions from the audience. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Fashion designer and judge of The Great British Sewing Bee, Patrick Grant, has a dream: he wants to create a line of jeans This week, the panellists tell us their favourite recipes for that made in Blackburn. It sounds simple, but Patrick wants to go classic savoury nibble, the cheese straw. They also delve into SAT 00:30 Hello, Stranger by Will Buckingham (m000yvbf) the whole hog - growing the crop to make the fabric in the world of fresh peas and, when it comes to cooking with this Episode 5 Blackburn, growing the woad to dye it blue in Blackburn and small green vegetable, our panellists are not quite peas in a pod! finally processing the flax into linen and sewing it all When Will Buckingham's partner died, he coped with his grief together...in Blackburn. Nigerian food writer Yemisi Aribisala explains the significance by throwing his doors open to new people, and travelling alone of soup in Nigerian cuisine, and tells us what goes into the to far-flung places among strangers. 'Strangers are unentangled In this programme, the writer and broadcaster Ian Marchant perfect jollof rice. in our worlds and lives,' he writes, 'and this lack can lighten our travels to a tiny field of flax on the side of the Leeds and own burdens.' Starting from that experience of personal grief, Liverpool Canal, where Patrick and a group of passionate local Producer: Hannah Newton he draws on his knowledge as a philosopher and anthropologist, people are trying to make this dream a reality, and bring the Assistant Producer: Aniya Das as well as a keen and wide-roaming traveller, to explore the textile industry back to Blackburn. -

Radio 4 Listings for 29 February – 6 March 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 29 February – 6 March 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 29 FEBRUARY 2020 Series 41 SAT 10:30 The Patch (m000fwj9) Torry, Aberdeen SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000fq5n) The Wilberforce Way with Inderjit Bhogal National and international news from BBC Radio 4 The random postcode takes us to an extraordinary pet shop Clare Balding walks with Sikh-turned-Methodist, Inderjit where something terrible has been happening to customers. Bhogal, along part of the Wilberforce Way in East Yorkshire. SAT 00:30 The Crying Book, by Heather Christle Inderjit created this long distance walking route to honour Torry is a deprived area of Aberdeen, known for addiction (m000fq5q) Wilberforce who led the campaign against the slave trade. They issues. It's also full of dog owners. In the local pet shop we Episode 5 start at Pocklington School, where Wilberforce studied, and discover Anna who says that a number of her customers have ramble canal-side to Melbourne Ings. Inderjit Bhogal has an died recently from a fake prescription drug. We wait for her Shedding tears is a universal human experience, but why and extraordinary personal story: Born in Kenya he and his family most regular customer, Stuart, to help us get to the bottom of it how do we cry? fled, via Tanzania, to Dudley in the West Midlands in the early - but where is he? 1960s. He couldn’t find anywhere to practice his Sikh faith so American poet Heather Christle has lost a dear friend to suicide started attending his local Methodist chapel where he became Producer/presenter: Polly Weston and must now reckon with her own depression. -

SPRING 2010 Dearwheaton

This version of Wheaton magazine does not contain the Class News section. s p r i n g 2 0 1 0 WHEATON The Litfin Legacy Continuity Amid Growth President Duane Litfin retires after 17 years Inside: Science Station Turns 75 • Remembering President Armerding • The Promise Report 150.WHEATON.EDU Wheaton College exists to help build the church and improve society worldwide by promoting the development of whole and effective Christians through excellence in programs of Christian higher education. This mission expresses our commitment to do all things “For Christ and His Kingdom.” volume 14 i s s u e 2 s PR i N G 2 0 1 0 6 a l u m n i n e w s departments 32 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters Open letter from Tim Stoner ’82, 5 News president of the Alumni Board 10 Sports 33 Wheaton Alumni Association News Association news and events 27 The Promise Report 37 Alumni Class News 56 Authors Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts from published alumnus Walter Wolfram ’63 Cover photo: President Litfin enjoys the lively bustle of the Sports and A Sentimental Journey Recreation Complex that was built in 2000 as a result of the New 58 Century Challenge. The only “brick-and-mortar” part of that campaign, An archival reflection from an alumna the SRC features a large weight room, three gyms, a pool, elevated Faculty Voice running track, climbing wall, dance and fitness studio, and wrestling 60 room, as well as classrooms, conference rooms, and a physiology lab. Dr. Nadine Folino-Rorem mentors biology Dr. -

Inside Science

SPRING 2009 NEWS FROM THE ROYAL SOCIETY INSIDE SCIENCE YOUNG EXPLORERS TOUCHDOWN IN NEW ZEALAND International Expedition Prize is a ‘once in a lifetime experience’ SCIENCE TAKES TO THE STAGE The Royal Shakespeare Company premiers a new play on the emergence of modern science UPDATE FROM THE ROYAL SOCIETY This third issue of Inside Science contains early information DID YOU KNOW? about exciting plans for the Royal Society’s 350th Anniversary in 2010. The Anniversary is a marvellous STEADY FOOTING, opportunity to increase the profile of science, explore its SHAKY BRIDGE benefits and address the challenges it presents for society On its opening day, crowds of but perhaps most important of all to inspire young minds pedestrians experienced unexpected with the excitement of scientific discovery. swaying as they walked across London’s Our policy work continues to address major scientific issues Millennium Bridge. Whilst pedestrians affecting the UK. In December we cautioned the Government on fondly nicknamed it the ‘wobbly bridge’, the levels of separated plutonium stockpiled in the UK – currently physicists were busy exploring the the highest in the world. With support from our Plutonium Working Group, the Society has reasons for the phenomenon. submitted detailed comment to the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) for a report to The view was widely held that the Government on management options for the stockpile. ‘wobble’ was due to crowd loading and Late last year we ran an extremely successful MP-Scientist pairing scheme, helping to build pedestrians synchronising their footsteps bridges between parliamentarians and some of the best young scientists in the UK. -

LIBRARY BOOKS.Xlsx

Cat No. Title Author Type 476 2,286 traditional stencil designs Roessing, H APPLIQUE 13 Afternoon Tea with May Morris Hill, Michele APPLIQUE 1094 Applique 12 Borders & Medallions Sienkiewicz, Elly APPLIQUE 1444 Applique 12 Easy Ways Sienkiewicz, Elly APPLIQUE Rodale's Successful Quilting 455 Applique made easy Library APPLIQUE 4 Applique Mastery Naylor, Philippa APPLIQUE 382 Applique outside the lines with Piece O' Cake Designs Goldsmith, Becky & Jenkins, Linda APPLIQUE 774 Applique, Applique, Applique Sinema, Laurene APPLIQUE 657 Artful applique II Townswick, Jane APPLIQUE 656 Artful applique the easy way Townswick, Jane APPLIQUE 251 At Play with Applique Fronks, Dilys A APPLIQUE Back to Front & New Approach to Machine Applique 1369 (2nd copy) Scouler, Larraine APPLIQUE 585 Baltimore Beauties & Beyond Vol 2 Sienkiewicz, Ely APPLIQUE 702 Baltimore blocks for beginners; a step-by-step guide Dietrich, Mimi APPLIQUE 404 Barbara Brackman's encyclopedia of applique Brackman, Barbara APPLIQUE Beautiful botanicals: 45 applique flowers & 14 quilt 520 projects Kemball, Deborah APPLIQUE 1751 Best of BaLtimore Beauties Sienkiewicz, Elly APPLIQUE 1783 Best of Jacobean Applique Campbell, Patricia B & Ayars, Mimi APPLIQUE Best-ever applique sampler from Piece O' Cake 684 Designs Goldsmith, Becky & Jenkins, Linda APPLIQUE 1842 Blossoms in Winter Eaton, Patti & Mostek, Pamela APPLIQUE 1795 Bouquet of Quilts Rounds & Rymer APPLIQUE 1594 Celtic Style Floral Applique Rose, Scarlett APPLIQUE 1998 Classic Four-Block Applique Quilts Marston, Gwen APPLIQUE 235 -

SUBSISTENCE, SETTLEMENT, and LAND-USE CHANGES DURING the MISSISSIPPIAN PERIOD on ST. CATHERINES ISLAND, GEORGIA by SARAH GREENHO

SUBSISTENCE, SETTLEMENT, AND LAND-USE CHANGES DURING THE MISSISSIPPIAN PERIOD ON ST. CATHERINES ISLAND, GEORGIA by SARAH GREENHOE BERGH (Under the Direction of Elizabeth J. Reitz) ABSTRACT This research examines the human-environment interactions on St. Catherines Island, Georgia, during the late Woodland through the Mississippian period (AD 800–1580). Results from multiple analyses indicate that socio-political, demographic, and economic changes during this period were associated with changes in subsistence, settlement, and land-use patterns. Archaeofaunal collections of vertebrates and invertebrates are examined from three sites in a single locality, representing human occupation during the entire Mississippian period—9LI21, 9LI229, and 9LI230. Two additional late Mississippian archaeofaunal collections of vertebrates are examined from different island locations—9LI207 and 9LI1637. Fine-grained recovery techniques, not previously used for Mississippian deposits on St. Catherines Island, produced collections dominated by estuarine resources, especially oysters, clams, stout tagelus, sea catfishes, mullets, killifishes, and drums. Previous methods used to recover faunal remains produced collections dominated by deer. This study suggests that, though deer contributed large amounts of meat to the diet, estuarine resources were more abundant and contributed the most meat. A Mississippian chiefdom developed on the island during the Irene phase (AD 1300– 1580), with social inequality, large and dense populations living in communities of multiple, integrated settlements, and maize farming. Zooarchaeological evidence presented in this study suggests these socio-political changes led to new human-environment interactions, compared to the early Mississippian period. Irene peoples used a larger number and wider variety of shellfishing and fishing locations than early Mississippian folk. The Irene fishing strategy caught more large fishes and may have involved a shift to larger-scale mass-capture techniques, such as weirs. -

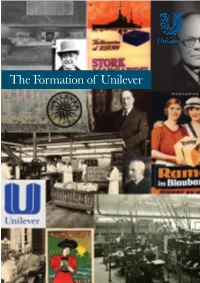

The Formation of Unilever 16944-Unilever 20Pp A5:Layout 1 15/11/11 14:35 Page 2

16944-Unilever 20pp A5:Layout 1 15/11/11 14:35 Page 1 The Formation of Unilever 16944-Unilever 20pp A5:Layout 1 15/11/11 14:35 Page 2 Unilever House, London, c1930 16944-Unilever 20pp A5:Layout 1 15/11/11 14:36 Page 03 In September 1929 an agreement was signed which created what The Economist described as "one of the biggest industrial amalgamations in European history". It provided for the merger in the following year of the Margarine Union and Lever Brothers Limited. The Margarine Union had been formed in 1927 by the Van den Bergh and Jurgens companies based in the Netherlands, and was later joined by a number of other Dutch and central European companies. Its main strength lay in Europe, especially Germany and the UK and its interests, whilst mostly in margarine and other edible fats, were also oil milling and animal feeds, retail companies and some soap production. Lever Brothers Limited was based in the UK but owned companies throughout the world, especially in Europe, the United States and the British Dominions. Its interests were in soap, toilet preparations, food (including some margarine), oil milling and animal feeds, plantations and African trading. One of the main reasons for the merger was competition for raw materials - animal and vegetable oils - used in both the manufacture of margarine and soap. However, the two businesses were very similar, so it made sense to merge as Unilever rather than continue to compete for the same raw materials and in the same markets. To understand how Unilever came into being you have to go back to the family companies that were instrumental in its formation. -

Transient Receptor Potential Channels As Drug Targets: from the Science of Basic Research to the Art of Medicine

1521-0081/66/3/676–814$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/pr.113.008268 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 66:676–814, July 2014 Copyright © 2014 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics ASSOCIATE EDITOR: DAVID R. SIBLEY Transient Receptor Potential Channels as Drug Targets: From the Science of Basic Research to the Art of Medicine Bernd Nilius and Arpad Szallasi KU Leuven, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Laboratory of Ion Channel Research, Campus Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium (B.N.); and Department of Pathology, Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, New Jersey (A.S.) Abstract. ....................................................................................679 I. Transient Receptor Potential Channels: A Brief Introduction . ...............................679 A. Canonical Transient Receptor Potential Subfamily . .....................................682 B. Vanilloid Transient Receptor Potential Subfamily . .....................................686 C. Melastatin Transient Receptor Potential Subfamily . .....................................696 Downloaded from D. Ankyrin Transient Receptor Potential Subfamily .........................................700 E. Mucolipin Transient Receptor Potential Subfamily . .....................................702 F. Polycystic Transient Receptor Potential Subfamily . .....................................703 II. Transient Receptor Potential Channels: Hereditary Diseases (Transient Receptor Potential Channelopathies). ......................................................704 -

Canadian Embroiderers Guild Guelph LIBRARY August 25, 2016

Canadian Embroiderers Guild Guelph LIBRARY August 25, 2016 GREEN text indicates an item in one of the Small Books boxes ORANGE text indicates a missing book PURPLE text indicates an oversize book BANNERS and CHURCH EMBROIDERY Aber, Ita THE ART OF JUDIAC NEEDLEWORK Scribners 1979 Banbury & Dewer How to design and make CHURCH KNEELERS ASN Publishing 1987 Beese, Pat EMBROIDERY FOR THE CHURCH Branford 1975 Blair, M & Ryan, Cathleen BANNERS AND FLAGS Harcourt, Brace 1977 Bradfield,Helen; Prigle,Joan & Ridout THE ART OF THE SPIRIT 1992 CEG CHURCH NEEDLEWORK EmbroiderersGuild1975T Christ Church Cathedral IN HIS HOUSE - THE STORY OF THE NEEDLEPOINT Christ Church Cathedral KNEELERS Dean, Beryl EMBROIDERY IN RELIGION AND CEREMONIAL Batsford 1981 Exeter Cathedra THE EXETER RONDELS Penwell Print 1989 Hall, Dorothea CHURCH EMBROIDERY Lyric Books Ltd 1983 Ingram, Elizabeth ed. THREAD OF GOLD (York Minster) Pitken 1987 King, Bucky & Martin, Jude ECCLESSIASTICAL CRAFTS VanNostrand 1978 Liddell, Jill THE PATCHWORK PILGRIMAGE VikingStudioBooks1993 Lugg, Vicky & Willcocks, John HERALDRY FOR EMBROIDERERS Batsford 1990 McNeil, Lucy & Johnson, Margaret CHURCH NEEDLEWORK, SANCTUARY LINENS Roth, Ann NEEDLEPOINT DESIGNS FROM THE MOSAICS OF Scribners 1975 RAVENNA Wolfe, Betty THE BANNER BOOK Moorhouse-Barlow 1974 CANVASWORK and BARGELLO Alford, Jane BEGINNERS GUIDE TO BERLINWORK Awege, Gayna KELIM CANVASWORK Search 1988 T Baker, Muriel: Eyre, Barbara: Wall, Margaret & NEEDLEPOINT: DESIGN YOUR OWN Scribners 1974 Westerfield, Charlotte Bucilla CANVAS EMBROIDERY STITCHES Bucilla T. Fasset, Kaffe GLORIOUS NEEDLEPOINT Century 1987 Feisner,Edith NEEDLEPOINT AND BEYOND Scribners 1980 Felcher, Cecelia THE NEEDLEPOINT WORK BOOK OF TRADITIONAL Prentice-Hall 1979 DESIGNS Field, Peggy & Linsley, June CANVAS EMBROIDERY Midhurst,London 1990 Fischer,P.& Lasker,A. -

School Annual for the Convents of the L.B.V.M in Australia

School Annual for the Convents of the l.B.V.M in Australia. Registered at G.P.O., Melbourne for transmission by Post as a Periodical. December, 1950 Vol. 6 December, 1950 MATER DEi. MATER MEA PICTURE OF ST . LUKE 'S MADONNA LORETO in which is incorporated Eucalyptus Blossoms (1886 -1924) School Annual of the l.B.V.M. in Australia "Tache, toi, d'etre vaill ante et bonne- ce sont Jes grandes quali tes des femmes." HIS HO LINESS, PO PE PIUS XII. So many of our Old Girls have gone to Rome for the Jubilee this year that the thoughts of members and friends of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin, all over the world, will recall with pleasure another Holy Year cele brated over three hundred years ago-in 1625. We go in spirit to Rome one day in that fa r-off year of Jubilee, and as we enter the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, we meet three ladies coming from their devotions. They are Mary V.I ard and two companions-the Found ress and the first Religious of the l.B.V.Af . Several Rpmans recognize them and stand back with deep respect, for they are already well loved by many thousands of parents whose children are being educated by them. T his basilica has been their favourite place of meditation and prayer since they came to Rome over three years ago. Near its sanctuary they have renewed their vows, and consecrated their lives anew to Our Lady of the Snows before the revered picture of St.