1 Draft of an Article for the Symposium On: Do We Really Need Linguistic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pidgin and Creole Languages: Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke

Pidgin and Creole Languages JOHN E. REINECKE 1904–1982 Pidgin and Creole Languages Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke Edited by Glenn G. Gilbert Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824882150 (PDF) 9780824882143 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1987 University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Preface viii Acknowledgments xii Introduction 1 John E. Reinecke: His Life and Work Charlene J. Sato and Aiko T. Reinecke 3 William Greenfield, A Neglected Pioneer Creolist John E. Reinecke 28 Theoretical Perspectives 39 Some Possible African Creoles: A Pilot Study M. Lionel Bender 41 Pidgin Hawaiian Derek Bickerton and William H. Wilson 65 The Substance of Creole Studies: A Reappraisal Lawrence D. Carrington 83 Verb Fronting in Creole: Transmission or Bioprogram? Chris Corne 102 The Need for a Multidimensional Model Robert B. Le Page 125 Decreolization Paths for Guyanese Singular Pronouns John R. -

Lexicostatistical Studies in East Sudanic II: the Case of Nyimang

George Starostin Russian State University for the Humanities, Moscow; National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow; Santa Fe Institute; [email protected] Lexicostatistical Studies in East Sudanic II: The Case of Nyimang The paper continues the authorʼs efforts to build up a lexicostatistical basis for the hypothesis of a genetic relationship between several African language groups and families collectively known as «East Sudanic». Here, on the basis of lexical comparison between core basic vocabu- laries, I argue that the small Nyimang language group of the Nuba Mountains is indeed ge- netically related to the «core Northeast Sudanic» trio of Nubian, Nara, and Tama, rather than to the much more distantly related Temein languages, also found in the Nuba Mountains. However, this relation may be even more distant than the one between Nubian, Nara, and Tama themselves. Additionally, it is shown that this issue is difficult to resolve without bring- ing into the comparison at least a limited amount of data from other potentially East Sudanic languages, bringing out the limitations of purely binary (or even ternary) comparison when it comes to establishing the genetic affiliation of small and chronologically remote linguistic entities. Keywords: East Sudanic languages; Nubian languages; Nara language; Nyimang languages; Tama languages; Temein languages; lexicostatistics; basic vocabulary. Introduction In my previous study, published as the first part of a series aimed at redefining the external borders, internal classification, and approximate age of the East Sudanic language family (Sta- rostin 2017), I have conducted a mixed lexicostatistical and etymological analysis of the basic lexicon (50-item wordlist subset) for the Nubian, Nara, and Tama language groups. -

The Afroasiatic Languages

CAMBRIDGE LANGUAGE SURVEYS Generaleditors P. Austin (University ofMelbourne) THE AFROASIATIC J. Bresnan (Stanford University) B. Comrie (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig) LANGUAGES S. Crain (University of Maryland) W. Dressler (University of Vienna) C. J. E wen ( University of Leiden) R. Lass (University of Cape Town) D. Lightfoot ( University of Mary/and) K. Rice (Vniversity ofToronto) I. Roberts (University of Cambridge) Edited by S. Romaine (University of Oxford) N. V. Smith (Vniversity College, London) ZYGMUNT FRAJZYNGIER This series offers general accounts of the major language families of the ERIN SHAY world, with volumes organized either on a purely genetic basis or on a geographical basis, whichever yields the most convenient and intelligible grouping in each case. Each volume compares and contrasts the typological features of the languages it deals with. lt also treats the relevant genetic relationships, historical development, and sociolinguistic issues arising from their role and use in the world today. The books are intended for linguists from undergraduate level upwards, but no special knowledge of the languages under consideration is assumed. Volumes such as those on Australia and the Amazon Basin are also of wider relevance, as the future of the languages and their speakers raises important social and political issues. Volumes already published include Chinese Jerry Norman The Languages of Japan Masayoshi Shibatani Pidgins and Creoles (Volume I: Theory and Structure; Volume II: Reference Survey) John A. Holm The Indo-Aryan Languages Colin Masica The Celtic Languages edited by Donald MacAulay The Romance Languages Rebecca Posner The Amazonian Languages edited by R. M. W. Dixon and Alexandra Y. -

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 19, Number 1, April 1988 MAJANG

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 19, Number 1, April 1988 MAJANG NOMINAL PLURALS, WITH COMPARATIVE NOTES* Peter Unseth Institute of Ethiopian Studies Addis Ababa University This paper describes the complex Majang system of noun plural formation. Majang uses singulative suffixes, plural suffixes, and suppletive plural stems to mark number on nouns. Majang is seen to exemplify in many ways the *N/*K pattern of singular and plural marking as described by Bryan [1968] for many Nilo-Saharan lan guages. Tiersma's [1982] theory of "Local Markedness" is shown to provide an explanation for singulative mark ing on some nouns in Majang and other Surma languages. A comparison of Majang noun plurals with plural forms in other Surma languages allows the reconstruction of some number marking for Proto-Surma. 1. Introduction Building on the work of Cerulli [1948] and Bender [1983b], this paper describes the marking of number on nouns in Majang, a Nilo-Saharan language spoken by 20,000-30,000 people in western Ethiopia. It is classified with in the Eastern Sudanic phylum, a member of the Surma group [Bender 1983a]. Fleming [1983:533] groups all Surma langauges except Majang into Southern Surma, placing Majang in a crucial position for the reconstruction of Proto- *1 conducted Majang fieldwork under the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University, from August 1984 to March 1986. Much of the data on noun plural formation was gathered with Anbessa Tefera, who was spon sored by the Research and Publications Committee of the Institute of Lan guage Studies, Addis Ababa University. I am grateful to the local offi cials who cooperated in making the fieldwork possible. -

Morphological Evidence for the Coherence of East Sudanic

article⁄Morphological Evidence for the Coherence of East Sudanic author⁄Roger M. Blench abstract⁄East Sudanic is the largest and most complex branch of Nilo-Saharan. First mooted by Greenberg in 1950, who included seven branches, it was expanded in his 1963 publication to include Ama (Nyimang) and Temein and also Kuliak, not now considered part of East Sudanic. However, demonstrating the coherence of East Sudanic and justifying an internal structure for it have remained problematic. The only signicant monograph on this topic is Bender’s The East Sudanic Languages, which uses largely lexical evidence. Bender proposed a subdivision into Ek and En languages, based on pronouns. Most subsequent scholars have accepted his Ek cluster, consisting of Nubian, Nara, Ama, and Taman, but the En cluster (Surmic, E. Jebel, Temein, Daju, Nilotic) is harder to substantiate. Rilly has put forward strong arguments for the inclusion of the extinct Meroitic language as coordinate with Nubian. In the light of these diculties, the paper explores the potential for morphology to provide evidence for the coherence of East Sudanic. The paper reviews its characteristic tripartite number-marking system, consisting of singulative, plurative, and an unmarked middle term. These are associated with specic segments, the singulative in t- and plurative in k- as well as a small set of other segments, characterized by complex allomorphy. These are well preserved in some branches, fragmentary in others, and seem to have vanished completely in the Ama group, leaving only traces now fossilized in Dinik stems. The paper concludes that East Sudanic does have a common morphological system, despite its internal lexical diversity. -

Areal Diffusion and Genetic Inheritance: Problems in Comparative Linguistics (Explorations in Linguistic Typology)

14 Convergence and Divergence in the Development of African Languages Bernd Heine and Tania Kuteva In the present chapter a bird's-eye view of some problems associated with contri- butions to the linguistic history (or prehistory, as some would say) of Africa is offered. It has been stimulated by recent contributions on linguistic methodology, especially by attempts to relate linguistic findings to more general observations on the evolution of the human species. The conclusion reached is that contact- induced language change and the implications it has for language classification in Africa are still largely a terra incognita. 1. Introduction For roughly half a century, work on the reconstruction of African languages and their relationship has been based on the work of Joseph Greenberg (1949,1955,1963). What this work has established in particular are findings such as the following: (a) The most easily accessible way of describing the historical relationship of these languages is by reconstructing their genetic relationship patterns. (b) The multitude of African languages can be reduced to four genetically defined units, called families by Greenberg and phyla by others. These units are Niger-Congo (or Niger-Kordofanian), Nilo-Saharan, Afroasiatic, and Khoisan. (c) There are various methods available to the linguist for historical reconstruc- tion. The task of the linguist is to choose that method that appears to be best suited to solve a particular problem. Which method is most suitable in a given The present paper is based on research that has been generously funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Society) to which we want to express our deeply felt grat- itude. -

Aethiopica 11 (2008) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies

Aethiopica 11 (2008) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies ________________________________________________________________ GROVER HUDSON, Michigan State University, East Lansing Personalia In memoriam Marvin Lionel Bender (1934߃2008) Aethiopica 11 (2008), 223߃234 ISSN: 1430߃1938 ________________________________________________________________ Published by UniversitÃt Hamburg Asien Afrika Institut, Abteilung Afrikanistik und £thiopistik Hiob Ludolf Zentrum fÛr £thiopistik Personalia In memoriam Marvin Lionel Bender (1934߃2008) GROVER HUDSON, Michigan State University, East Lansing Marvin Lionel Bender, a prominent figure in Afroasiatic and Ethiopian linguistics for 50 years and whose works are among the authoritative sources on Omotic and Nilo-Saharan linguistics, died on Tuesday, February 19, 2008 in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. Born August 18, 1934 in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, he received Bache- lor߈s and Master߈s degrees from Dartmouth College in mathematics (1956, 1958). After M.A. studies, Bender taught mathematics in Ghana and then in Ethiopia at Haile Sellassie I University, where he became interested in Ethio- pian languages and linguistics, and so returned to graduate school at the Uni- versity of Texas at Austin, where his 1968 dissertation was directed by Emmon Bach. After Ph.D. studies, Bender was immediately recruited to the research team of the Language Survey of Ethiopia, a Ford Foundation project and part of the five-nation Survey of Language Use and Language Teaching in East Africa. He was the only member -

Saharan and Songhay Form a Branch of Nilo-Saharan

SAHARAN AND SONGHAY FORM A BRANCH OF NILO-SAHARAN DRAFT ONLY NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Ans 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Saharan and Songhay form a branch of Nilo-Saharan Roger Blench & Lameen Souag Draft TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION: A SONGHAY-SAHARAN ALIGNMENT?............................................................ 1 2. SONGHAY................................................................................................................................................... 1 3. SAHARAN................................................................................................................................................... 3 4. TABLES OF LEXICAL SIMILARITIES ................................................................................................ 6 4.1 Nouns ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 4.1.1 Body part, fluids............................................................................................................................... 6 4.1.2 Persons ............................................................................................................................................. 9 4.1.3 Animals and plants........................................................................................................................ -

9 Africa's Verb-Final Languages

9 Africa’s verb-final languages Gerrit J. Dimmendaal 9.1 The verb-final type in a crosslinguistic perspective The position of the verb relative to other constituents within a clause has been claimed by a number of authors to be a predictor of an additional set of syntactic features. Thus, according to Greenberg (1966), verb-initial languages tend to be prepositional rather than postpositional, putting inflected auxiliary verbs before rather than after the main verb; with more than chance frequency, verb-final languages tend to use postpositions, with auxiliary verbs following the main verb. Such inductively based generalizations about the nature of language of course require further analyses and explanations, e.g. in terms of preferred parsing or processing structures for the human mind. In more recent correlative studies of this type, e.g. by Dryer (1992), a distinction is drawn between phrasal and non-phrasal elements. Whereas phrasal elements, such as subject and object phrases or adpositions appear to follow a more consistent right-branching or left-branching pattern cross- linguistically, the position of non-phrasal categories such as adjectives, demonstratives, negative particles, or tense–aspect markers does not seem to correlate with constituent order type, as argued by Dryer. Obviously, constituent order is but one of various factors determining the typological portrait of a language, morphological techniques used in expres- sing syntactic and semantic relations being another important parameter. This latter observation of course is not new; Sapir (1921:120–46) already pointed out that languages may differ considerably in the techniques used for the expression of syntactic relations. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 11:31:20AM Via Free Access What to Do When You Are Unhappy with Language Areas but You Do Not Want to Quit 113

WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU ARE UNHAPPY WITH LANGUAGE AREAS BUT YOU DO NOT WANT TO QUIT Mauro Tosco Università di Napoli “L’Orientale”, Naples, Italy 1. Back to the roots: Trubetzkoy’s areas and the weight of ideology1 Contrary to a widely shared opinion (cf. e.g. Stolz 2002—one of the best critiques of the overuse and misuse of language areas), Trubetzkoy did not come up with his concept of Sprachbund in 1928 on the occasion of the 1st International Congress of Linguists at The Hague: he had already developed it a few years earlier and, interestingly enough, in a work not dealing at all, at least in primis, with languages, nor written for linguists. According to Toman (1995), Trubetzkoy first published his ideas on Sprachbünde as early as 1923 in a theological treatise in Russian, The Tower of Babel and the Confusion of Languages. Trubetzkoy, at that time in exile in Sofia, was developing his famous Eurasian ideology. There is much more than a chronological coincidence here: as aptly emphasized by Toman (1995), the whole concept of Sprachbund had in Trubetzkoy much more than strong ideological underpinnings—it was perhaps ideologically motivated. Not only Trubetzkoy underplays genetic classifications; to him, this is part of a wider rejection of hierarchical and evolutionary models. The resulting cultural relativism was instrumental to Trubetzkoy’s rejection of European civilization, considered foreign to Russia. Languages (and cultures) are viewed as linked in a chain, or as a net: because the transitions from one segment to another are gradual, the entire system of the languages of the globe still represents a definite, although only intellectually perceivable whole [...] the existence of the Law of Fragmentation in the domain of language does not lead to an anarchic dispertion, but to a harmonious system (Trubetzkoy 1923:116, quoted in Toman 1995:205). -

250 Marvin Lionel Bender (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 18.8

250 KRONIKA Marvin Lionel Bender (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 18.8. 1934 – Cape Girardeau, Missouri 19.2. 2008) Na počátku roku 2008 skončil svou životní pouť jeden z nejpozoruhodnějších afrikanistů posled- ního půlstoletí. Akademickou dráhu započal studiem matematiky na Dartmouth College, kde získal jak bakalářský, tak magisterský titul (1956, 1958). Své doktorské studium na Yale však přerušil a vydal se přednášet matematiku na africké univerzity. Započal na Adisadel College v Cape Coast v Ghaně, poté se přesunul do Entebbe v Ugandě. Odtud si udělal výlet do Etiopie, který se mu stal svým způsobem osudným. Zemi a její obyvatele si natolik zamiloval, že se rozhodl zde zůstat. Podařilo se mu získat pozici na Univerzitě Haile Sellassie I. v Addis Ababě. Zde odstartoval jeho zájem o jazyky Etiopie, které ho fascinovaly po celý jeho zbývající život. Nejprve se rozhodl doplnit si lingvistické vzdělání na univerzitě v texaském Austinu, kde r. 1968 obhájil disertaci o amharské slovesné morfologii (srov. 1978). Do Etiopie se vrátil, právě když se zde rozjížděl projekt Language Survey of Ethiopia, financovaný Fordovou nadací. Zapojil se jak do sběru materiálu v terénu, tak do jeho vyhodnocování a též editorské činnosti (1971, 1975b, c, 1976a, b, 1977). Etiopský projekt dokončoval na univerzitě ve Stanfordu, kde navázal spolupráci s J.H. Greenbergem. Vedle Etiopie se věnoval terénnímu výzkumu také v Sudánu, kam se dostal díky Fulbrightovu stipendiu, a to v letech 1978–79. Od r. 1971 do svého penzionování působil na katedře antropologie na Jihoillinoiské univer- zitě v Carbondale. Svým způsobem revoluční byla v 60. a 70. letech 20. st. Benderova systematická aplikace kvantitativních metod při posuzování genetických vztahů mezi jazyky nejen Etiopie. -

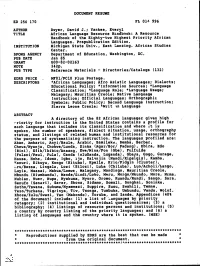

African Language Resource Handbook: a Resource Handbook of the Eighty-Two Highest Priority African Languages

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 256 170 FL 014 996 AUTHOR Dwyer, David J.; Yankee, Everyl TITLE African Language Resource Handbook: A Resource Handbook of the Eighty-two Highest Priority African Languages. Prepublication Edition. INSTITUTION Michigan State Univ., East Lansing. African Studies Center. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE Jan 85 GRANT G00-82-02163 NOTE 242p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE , MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African Languages; Afro Asiatic Languages; Dialects; Educational Policy; *Information Sources; *Language Classification; *Language Role; *Language Usage; Malagasy; Mauritian Creole; Native Language Instruction; Official Languages; Orthographic Symbols; Public Policy; Second Language Instruction; Sierra Leone Creole; *Writ In Language ABSTRACT A directory of the 82 African languages given high rriority for instruction in the United States contains a profile for each language that includes its classification and where It is spoken, the number of speakers, dialect situation, usage, orthography status, and listings of related human and institutional resourcesfor the purpose of systematizing instruction. The languages profiled are: Akan, Amharic, Anyi/Baule, Arabic, Bamileko, Bemba, Berber, Chewa/Nyanja, Chokwe/Lunda, Dinka (Agar/Bor/ Padang), Ebira, Edo (Bini), Efik/Ibibio/Anaang, Ewe/Mina/Fon (Gbe), Fulfulde (Fulani/Peul, Fula), Ganda (oluGanda, Luganda), Gbaya, Gogo, Gurage, Hausa, Hehe, Idoma, Igbo, ijo, Kalnnjin(Nandi/Kipsigis), Kamba, Fanuri, Kikuyu,