Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anexe La H.C.G.M.B. Nr. 254 / 2008

NR. FELUL LIMITE DENUMIREA SECTOR CRT. ARTEREI DELA ..... PANA LA ..... 0 1 2 3 4 5 1 Bd. Aerogarii Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti Bd. Ficusului 1 2 Str. Avionului Sos. Pipera Linie CF Constanta 1 3 Bd. Averescu Alex. Maresal Bd. Ion Mihalache Sos. Kiseleff 1 4 Bd. Aviatorilor Pta Victoriei Sos. Nordului 1 5 P-ta Aviatorilor 1 6 Str. Baiculesti Sos. Straulesti Str. Hrisovului 1 7 Bd. Balcescu Nicolae Bd. Regina Elisabeta Str. CA Rosetti 1 8 Str. Baldovin Parcalabul Str. Mircea Vulcanescu Str. Cameliei .(J' 9 Bd. Banu Manta Sos. Nicolae Titulescu Bd. Ion Mihalache /'co 1 ~,..~:~':~~~.~. (;~ 10 Str. Beller Radu It. avo Calea Dorobanti Bd. Mircea Eliade ,i: 1 :"~," ~, ',.." " .., Str. Berzei ,;, 1 t~:~~:;:lf~\~l'~- . ~: 11 Str. Berthelot Henri Mathias, G-ral Calea Victoriei .. ~!- .~:,.-::~ ",", .\ 1.~ 12 P-ta Botescu Haralambie ~ . 13 Str. Berzei Calea Plevnei Calea Grivitei 1 ~; 14 Str. Biharia Bd. Aerogarii Str. Zapada Mieilor 1 15 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti P-ta Presei Libere Str. Elena Vacarescu 1 16 Sos. Bucuresti Targoviste Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos.Odaii 1 17 Bd. Bucurestii Noi Calea Grivitei Sos. Bucurestii Targoviste 1 18 Str. Budisteanu Ion Str. G-ral Berthelot Calea Grivitei 1 19 Str. Buzesti Calea Grivitei P-ta Victoriei 1 20 P-ta Buzesti 1 21 Str. Campineanu Ion Str. Stirbei Voda Bd. Nicolae Balcescu 1 22 Str. Caraiman Calea Grivitei Bd. Ion Mihalache 1 23 Str. Caramfil Nicolae Sos. Nordului Str. Av. AI. Serbanescu 1 24 Bd. Campul Pipera Aleea Privighetorilor 1 25 P-ta Charles de Gaulle -'- 1 26 Sos. Chitilei ,.".ll·!A Bd. Bucurestii Noi Limita administrativa - 1 27 Str. -

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

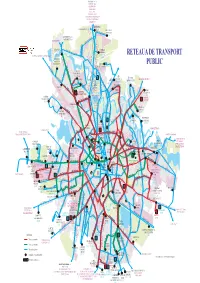

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

Download This PDF File

THE SOCIO-SPATIAL DIMENSION OF THE BUCHAREST GHETTOS Viorel MIONEL Silviu NEGUŢ Viorel MIONEL Assistant Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 Email: [email protected] Abstract Based on a socio-spatial analysis, this paper aims at drawing the authorities’ attention on a few Bucharest ghettos that occurred after the 1990s. Silviu NEGUŢ After the Revolution, Bucharest has undergone Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, many socio-spatial changes. The modifications Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of that occurred in the urban perimeter manifested Economic Studies Bucharest, Romania in the technical and urban dynamics, in the urban Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 infrastructure, and in the socio-economic field. The Email: [email protected] dynamics and the urban evolution of Bucharest have affected the community life, especially the community homogeneity intensely desired during the communist regime by the occurrence of socially marginalized spaces or ghettos as their own inhabitants call them. Ghettos represent an urban stain of color, a special morphologic framework. The Bucharest “ghettos” appeared by a spatial concentration of Roma population and of poverty in zones with a precarious infrastructure. The inhabitants of these areas (Zăbrăuţi, Aleea Livezilor, Iacob Andrei, Amurgului and Valea Cascadelor) are somehow constrained to live in such spaces, mainly because of lack of income, education and because of their low professional qualification. These weak points or handicaps exclude the ghetto population from social participation and from getting access to urban zones with good habitations. -

Trasee De Noapte

PROGRAMUL DE TRANSPORT PENTRU RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE - TRASEE DE NOAPTE Plecari de la capete de Linia Nr Numar vehicule Nr statii TRASEU CAPETE lo traseu Lungime c 23 00:30 1 2 03:30 4 5 Prima Ultima Dus: Şos. Colentina, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. Ferdinand, Şos. Pantelimon, Str. Gǎrii Cǎţelu, Str. N 101 Industriilor, Bd. Basarabia, Bd. 1 Dus: Decembrie1918 0 2 2 0 2 0 0 16 statii Intors: Bd. 1 Decembrie1918, Bd. 18.800 m Basarabia, Str. Industriilor, Str. Gǎrii 88 Intors: Cǎţelu, Şos. Pantelimon, Bd. 16 statii Ferdinand, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Şos. 18.400 m Colentina. Terminal 1: Pasaj Colentina 00:44 03:00 Terminal 2: Faur 00:16 03:01 Dus: Piata Unirii , Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Universitatii, Bd. Carol I, Bd. Pache Protopopescu, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Str. Vatra Luminoasa, Bd. N102 Pierre de Coubertin, Sos. Iancului, Dus: Sos. Pantelimon 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 19 statii Intors: Sos. Pantelimon, Sos. Iancului, 8.400 m Bd. Pierre de Coubertin, Str. Vatra 88 Intors: Luminoasa, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. 16 statii Pache Protopopescu, Bd. Carol I, 8.600 m Piata Universitatii, Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Unirii. Terminal 1: Piata Unirii 2 23:30 04:40 Terminal 2: Granitul 22.55 04:40 Dus: Bd. Th. Pallady, Bd. Camil Ressu, Cal. Dudeşti, Bd. O. Goga, Str. Nerva Traian, Cal. Văcăreşti, Şos. Olteniţei, Str. Ion Iriceanu, Str. Turnu Măgurele, Str. Luică, Şos. Giurgiului, N103 Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei, Bd. Pieptănari, us: Prelungirea Ferentari 0 2 1 0 2 0 0 24 statii Intors: Prelungirea Ferentari, , Bd. -

Roma As Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania

Roma as Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Roderick Charles Lawford DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated, and the thesis has not been edited by a third party beyond what is permitted by Cardiff University’s Policy on the Use of Third Party Editors by Research Degree Students. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… ii To Sue Lawford and In Memory of Marion Ethel Lawford (1924-1977) and Charles Alfred Lawford (1925-2010) iii Table of Contents List of Figures vi List of Plates vii List of Tables ix Conventions x Acknowledgements xii Abstract xiii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 - Theory and Method -

Bucharest Barks: Street Dogs, Urban Lifestyle Aspirations, and the Non-Civilized City

Bucharest Barks: Street Dogs, Urban Lifestyle Aspirations, and the Non-Civilized City by Lavrentia Karamaniola A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Krisztina E. Fehérváry, Co-Chair Professor Alaina M. Lemon, Co-Chair Professor Liviu Chelcea, University of Bucharest Associate Professor Matthew S. Hull Professor Robin M. Queen “The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.” “I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one's burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Extracts from “Sisyphus Myth” (1942) by Albert Camus (1913–1960) Sisyphus by Titian (1490–1567) 1548–1549. Oil on canvas, 237 x 216 cm Prado Museum, Madrid Lavrentia Karamaniola [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2194-3847 © Lavrentia Karamaniola 2017 Dedication To my family, Charalambos, Athena, Yannis, and Dimitris for always being close, for always nourishing their birbilo, barbatsalos, kounioko and zoumboko To Stefanos, for always smoothing the road for me to push the rock uphill ii Acknowledgments This project could not have been possible without the generous and continuous support of a number of individuals and institutions. -

Autobuze.Pdf

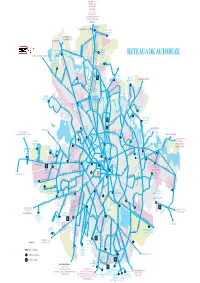

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 261 BANEASA RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE 204 205 304 Sisesti 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 112 205 261 COMPLEX 131 261301 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti COMERCIAL CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucu Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 COLOSSEUM 203 335 361 605 780 783 Bd.R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 112 Aerogarii R402 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 restii Noi DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 331 R436 CFR 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 112 135 243 Str. Jiului Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Sos. Chitilei 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Poligrafiei 231 243 Str. Peris 780 783 331 PIATA Str.Oi 243 382 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 243 382 R447PRESEI R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 243 131 203 205 261 304 135 343 105 203 231 tuz CARTIER 261 304 330 361 605 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 Bd. Marasti GIULESTI-SARBI 162 R441 R442 R443 r a lo c i s Bd. Expozitiei231 330 r o a dronache 162 163 105 780 R444 R446t e R409 243 343 Str. Sportului a r 105 i CLABUCET R447 o v l F 381 R448 A . -

City of Bucharest

City of Bucharest Intercultural Profile 1. Background1 Bucharest is the capital and largest city, as well as the cultural, industrial, and financial centre of Romania. According to the 2011 census, 1,883,425 inhabitants live within the city limits, a decrease from the 2002 census. Taking account of the satellite towns around the urban area, the proposed metropolitan area of Bucharest would have a population of 2.27 million people. However, according to unofficial data given by Wikipedia, the population is more than 3 million (raising a point that will be reiterated throughout this report that statistics are not universally reliable in Romania).Notwithstanding, Bucharest is the 6th largest city in the European Union by population within city limits, after London, Berlin, Madrid, Rome, and Paris. Bucharest accounts for around 23% of the country’s GDP and about one-quarter of its industrial production, while being inhabited by only 10% of the country’s population. In 2010, at purchasing power parity, Bucharest had a per-capita GDP of EUR 14,300, or 45% that of the European Union average and more than twice the Romanian average. Bucharest’s economy is mainly focused on industry and services, with a significant IT services sector. It houses 186,000 companies, and numerous companies have set up headquarters in Bucharest, attracted by the highly skilled labour force and low operating costs. The list includes multinationals such as Microsoft, IBM, P&G, HP, Oracle, Wipro, and S&T. In terms of higher education, Bucharest is the largest Romanian academic centre and one of the most important locales in Eastern Europe, with 16 public and 18 private institutes and over 300,00 students. -

Residential Areas with Deficient Access to Urban Parks in Bucharest – Priority Areas for Urban Rehabilitation

ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS and DEVELOPMENT Residential areas with deficient access to urban parks in Bucharest – priority areas for urban rehabilitation CRISTIAN IOJA, MARIA PATROESCU, LIDIA NICULITA, GABRIELA PAVELESCU, MIHAI NITA, ANNEMARIE IOJA Centre for Environmental Research and Impact Studies, University of Bucharest 1 Nicolae Balcescu Blvd., Sector 1, Bucharest, ROMANIA Abstract: - The paper emphasizes the real dimension of the urban parks surfaces deficit upon the built environment in Bucharest city. There were established residential area categories with deficient access to urban parks of high quality, considered to be priority intervention areas for urban rehabilitation (residential areas situated at more than 3 km from municipal importance parks, at more than 1 km from urban parks, residential areas with access to crowded parks, or with access to parks that have degraded endowments). Deficient access to Bucharest urban parks was correlated with the development projects of new residential quarters, being obviously the tendency of city suffocation under the pressure of constructed surfaces and agglomeration. Key-Words: - urban parks, residential areas, housing, Bucharest, rehabilitation priorities areas 1 Introduction residential areas was completed by a tendency of Green spaces represent an essential component in vertical development, initially through 4 floors large urban environments, to which they offer constru-ctions, then 9 and 10 floors, in the present numerous direct and indirect services (improving reaching 20 floors. These new residential surfaces environmental quality, recreation and leisure, accentuated the real deficit of public green spaces. climate amelioration etc.) [1], [2], [3]. Green spaces deficit is expressed through the degradation of housing conditions in urban environments [1], [2], [3], automatically determining an increase of housing costs [4], a degradation of the population’s health state [5], [6] and the appearance of social segregation problems [7], [8]. -

Making and Living in Romania's Postsocialist Slum

Eurasian Geography and Economics ISSN: 1538-7216 (Print) 1938-2863 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rege20 The modern mahala: making and living in Romania’s postsocialist slum Dominic Teodorescu To cite this article: Dominic Teodorescu (2019): The modern mahala: making and living in Romania’s postsocialist slum, Eurasian Geography and Economics, DOI: 10.1080/15387216.2019.1574433 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2019.1574433 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 11 Feb 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rege20 EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2019.1574433 The modern mahala: making and living in Romania’s postsocialist slum Dominic Teodorescu Department of Social and Economic Geography, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Almost 30 years have passed since state-socialism came to an Received 21 March 2018 end, and several scholars sought to establish how the Accepted 23 December 2018 Romanian housing market has unfolded within a changing KEYWORDS economic context and a strongly altered welfare system. This Postsocialist city; Bucharest; paper considers the most disadvantaged postsocialist groups segregation; mahala; in Romanian society and aims to advance our understanding homeownership; tenure of the housing situation in newly concentrated poor urban insecurity spaces. In developing such analysis, this article draws on local insights from Ferentari, a neighborhood in Bucharest where most residents I spoke saw a gradual degradation of their dwelling and living environment and do not expect any improvement soon. -

Component 1. Elaboration of Bucharest's Iuds, Capital

ROMANIA Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program (P169577) COMPONENT 1. ELABORATION OF BUCHAREST’S IUDS, CAPITAL INVESTMENT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT Output 3. Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS, and identification of a longlist of projects Chapter 1. Socio-economic profile March 2021 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Romanian Government. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) the Municipality of Bucharest (Bd. Regina Elisabeta 47, Bucharest, Romania); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Str. Vasile Lascăr 31, et. 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania). This report was delivered in March 2021 under the Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program, concluded between the Municipality of Bucharest and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development on March 4, 2019. It is part of Output 3 under the above-mentioned agreement – Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and vision and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects – under Component 1, which refers to the elaboration of Bucharest’s Integrated Urban Development Strategy, Capital Investment Planning and Management . -

A Proposal for a New Administrative-Territorial Outline of Bucharest-Based In-City Discontinuities

DOI:10.24193/tras.56E.5 Published First Online: 02/28/2019 A PROPOSAL FOR A NEW ADMINISTRATIVE-TERRITORIAL OUTLINE OF BUCHAREST-BASED IN-CITY DISCONTINUITIES Radu SĂGEATĂ Radu SĂGEATĂ Researcher, Institute of Geography, Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 0040-213-135.990 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Urban development represents a perma- nent challenge for space organization in large cities. Space organization is to be achieved by observing the homogeneity and specifi city of dwelling cores (urban quarters) as premises for urban structure functionality and viability. The administrative boundaries should overlap discontinuity areas in the city, which cause di- vergent population fl ows. The radial-concentric type morphostructure of Bucharest, Romania’s capital-city, is based on the sectorial model of six administrative sectors, in this case. Each sec- tor has both central and peripheral zones, with sharper inter-sectorial than intra-sectorial dispar- ities. Massive industrialization and urbanization in the socialist period led to the development of the housing stock and the individualization of quarter centers as secondary polarization cores in the city. This situation calls for revisiting the current administrative boundaries in the light of city discontinuities and establishing some multi- core sectors by encompassing homogeneous quarters in terms of functionality, specifi city, and social-urbanistic problems, so that administra- tive and local development policies could better match the concrete situations on the ground. Keywords: urban morphostructure, admin- istrative sectors, quarter centers, discontinuities, functionality, Bucharest. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 77 No. 56 E/2019 pp. 77-96 1. Introduction. Targets Urban expansion calls for an ever more complex management of city areas.