The Rhetoric of Feminist Hashtags and Respectability Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hegemonic Masculinity and Humor in the 2016 Presidential Election

SRDXXX10.1177/2378023117749380SociusSmirnova 749380research-article2017 Special Issue: Gender & Politics Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World Volume X: 1 –16 © The Author(s) 2017 Small Hands, Nasty Women, and Bad Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Hombres: Hegemonic Masculinity and DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117749380 10.1177/2378023117749380 Humor in the 2016 Presidential Election srd.sagepub.com Michelle Smirnova1 Abstract Given that the president is thought to be the national representative, presidential campaigns often reflect the efforts to define a national identity and collective values. Political humor provides a unique lens through which to explore how identity figures into national politics given that the critique of an intended target is often made through popular cultural scripts that often inadvertently reify the very power structures they seek to subvert. In conducting an analysis of 240 tweets, memes, and political cartoons from the 2016 U.S. presidential election targeting the two frontrunners, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, we see how popular political humor often reaffirmed heteronormative assumptions of gender, sexuality, and race and equated scripts of hegemonic masculinity with presidential ability. In doing so, these discourses reified a patriarchal power structure. Keywords gender, hegemonic masculinity, memes, humor, politics Introduction by which patriarchal power subjugates or excludes women, the LGTBQ community, people of color, and other marginal- On November 8, 2016, Republican candidate Donald Trump ized populations. Hegemonic masculinity is directly linked was elected president of the United States over Democratic to patriarchy in that it exists as the form of masculinity that candidate Hillary Clinton. Gender was a particularly salient is “culturally exalted” in a particular historical and geograph- feature of the 2016 U.S. -

Donald Trump Shoots the Match1 Sharon Mazer

Donald Trump Shoots the Match1 Sharon Mazer The day I realized it can be smart to be shallow was, for me, a deep experience. —Donald J. Trump (2004; in Remnick 2017:19) I don’t care if it’s real or not. Kill him! Kill him! 2 He’s currently President of the USA, but a scant 10 years ago, Donald Trump stepped into the squared circle, facing off against WWE owner and quintessential heel Mr. McMahon3 in the “Battle of the Billionaires” (WrestleMania XXIII). The stakes were high. The loser would have his head shaved by the winner. (Spoiler alert: Trump won.) Both Trump and McMahon kept their suits on—oversized, with exceptionally long ties—in a way that made their heads appear to hover, disproportionately small, over their bulky (Trump) and bulked up (McMahon) bodies. As avatars of capitalist, patriarchal power, they left the heavy lifting to the gleamingly exposed, hypermasculinist bodies of their pro-wrestler surrogates. McMahon performed an expert heel turn: a craven villain, egging the audience to taunt him as a clueless, elitist frontman as he did the job of casting Trump as an (unlikely) babyface, the crowd’s champion. For his part, Trump seemed more mark than smart. Where McMahon and the other wrestlers were working around him, like ham actors in an outsized play, Trump was shooting the match: that is, not so much acting naturally as neglecting to act at all. He soaked up the cheers, stalked the ring, took a fall, threw a sucker punch, and claimed victory as if he (and he alone) had fought the good fight (WWE 2013b). -

Capuzza and Daily Capitalized on the Energy Created by the March to Achieve Their Ends (Cochrane, 2017)

Women & Language We March On: Voices from the Women’s March on Washington Jamie C. Capuzza University of Mount Union Tamara Daily University of Mount Union Abstract: Protest marches are an important means of political expression. We investigated protesters’ motives for participating in the original Women’s March on Washington. Two research questions guided this study. First, to what degree did concerns about gender injustices motivate marchers to participate? Second, to what degree did marchers’ motives align with the goals established by march organizers? Seven-hundred eighty-seven participants responded to three open-ended questions: (1) Why did you choose to participate in the march, (2) What did you hope to accomplish, and (3) What events during the 2016 presidential election caused you the greatest concern? Responses were coded thematically. Findings indicated that gender injustices were not the sole source of motivation. Most respondents were motivated to march for a variety of reasons, hoped the march would function as a show of solidarity and resistance, and indicated that the misogynistic rhetoric of the 2016 presidential campaign was a deep concern. Finally, the comparison of respondents’ motives and organizers’ stated goals indicated a shared sense of purpose for the march. Keywords:feminism, Women’s March, political communication, motive, intersectionality ON JANUARY 21, 2017, AN ESTIMATED seven million people joined together across all seven continents in one of the largest political protests the world has witnessed. The Women’s March on Washington, including its over 650 sister marches, is considered the largest of its kind in U.S. history (Chenoweth & Pressman, 2017; Wallace & Parlapiano, 2017), and it is one of the most significant political and rhetorical events of the contemporary women’s movement. -

President's Report

· mount holyoke · PRESIDENT’S REPORT · a note from the · PRESIDENT The College has always been a place where big visions take shape. For over 180 years, we have opened opportunities for students to deepen their understanding and sharpen their response to a fast-changing world with challenges both known and unknown. We prepare students to learn and to lead because in life and work, we know this is what makes all the difference. Now that we have been deeply engaged in the work for two years of our five-year Plan for 2021, I’m delighted to share our progress, including an overview of some of Mount Holyoke’s new strategic initia- tives. In January 2018, we opened the Dining Commons, a part of the new Community Center, which is now also nearing completion. With the extensive renovations to Blanchard Hall we are creating a co-curricular hub in support of student leadership and programs, as well as a coffee shop and pub. We’ve also added new residential, co-curricular, and academic spaces. These spaces are the heart of our community-building efforts, giving more attention to shared endeavors and creating a sense of belonging. They represent a commitment to place at Mount Holyoke, reminding us all of the power of relationships that is in the very warp and woof of the College and the Alumnae Association. There is an energy and excitement to our being in the same space at the same times each day to eat, talk, think, and debate in companionship and cooperation. I hope the stories in these pages excite you about our current initi atives and our plans for the future. -

Pdf, 306.71 KB

Trends Like These 242: Warren Releases Healthcare Plan, Fake Bridezilla Dramatic Reading, Richard Spencer’s True Form, Trump Owes $2M for Sham Charity, Jeffrey Epstein Autopsy Findings, Massive AirBnb Scam, Trump Jr. is Still a Jerk Published on November 8th, 2019 Listen on TheMcElroy.family Brent: This week: McDonald‘s CEO gets canned, Elizabeth Warren‘s brand new plan, and Popeye‘s we stan. Courtney: I'm Courtney Enlow. Brent: I'm Brent Black. Courtney: And I'm going to need an extra week off life! Brent: With Trends Like These. Brent: Hello, Courtney. Courtney: Hello, Brent! Brent: We are doing a show… get this, get this. And I can't stress this enough… about trending news! Courtney: What? [laughs] Oh my god. Brent: I know! Which timeline did we end up in? Courtney: It'll never catch on. Brent: Well, we‘ll give it a college try. Courtney: Yeah. Brent: Um… welcome to Trends Like These, real life friends talking internet trends. It‘s what we do. This week is a Courtney and Brent twofer. A two- hander, as you might say in the theater. Courtney: And y'know what? I actually—this episode is where we are going to introduce the Courtney and Brent theatrical players. Brent: Yes. Courtney and Brent repertory theater. Courtney: Yes. It‘s going to be a thing of beauty and joy forever. Brent: Well, at least your part. We‘ll see. Courtney: [sings] Foreverrr… Brent: I'll dust off my acting skills. Um… Courtney: Hey, Brent. Really important question. And I already know the answer, but it‘s basically like a pretend question to like, get us into like, a fun conversation. -

Dismantling Respectability: the Rise of New Womanist Communication

Journal of Communication ISSN 0021-9916 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Dismantling Respectability: The Rise of New Womanist Communication Models in the Era Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/joc/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/joc/jqz005/5370149 by guest on 07 March 2019 of Black Lives Matter Allissa V. Richardson Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA Legacy media coverage of the Civil Rights Movement often highlighted charismatic male leaders, such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., while scores of Black women worked qui- etly in the background. Today’s leaders of the modern Black Lives Matter movement have turned this paradigm on its face. This case study explores the revamped communi- cation styles of four Black feminist organizers who led the early Black Lives Matter Movement of 2014: Brittany Ferrell, Alicia Garza, Brittany Packnett, and Marissa Johnson. Additionally, the study includes Ieshia Evans: a high-profile, independent, anti–police brutality activist. In a series of semi-structured interviews, the women shared that their keen textual and visual dismantling of Black respectability politics led to a mediated hyper-visibility that their forebearers never experienced. The women share the advantages and disadvantages of this approach, and weigh in on the sustain- ability of their communication methods for future Black social movements. Keywords: Black Feminism, Political Communication, Twitter, Respectability Politics, Social Movements. doi:10.1093/joc/jqz005 Brittany Ferrell remembered the tear gas most. As a frontline demonstrator during what came to be known as the Ferguson protests in August 2014, she recalled the unimaginable sting in her lungs and nose as she gasped for air. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Donald Had Started Branding All of His Buildings in Manhattan, My Feelings About My Name Became More Complicated

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook. Join our mailing list to get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox. For my daughter, Avary, and my dad If the soul is left in darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but the one who causes the darkness. —Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Author’s Note Much of this book comes from my own memory. For events during which I was not present, I relied on conversations and interviews, many of which are recorded, with members of my family, family friends, neighbors, and associates. I’ve reconstructed some dialogue according to what I personally remember and what others have told me. Where dialogue appears, my intention was to re-create the essence of conversations rather than provide verbatim quotes. I have also relied on legal documents, bank statements, tax returns, private journals, family documents, correspondence, emails, texts, photographs, and other records. For general background, I relied on the New York Times, in particular the investigative article by David Barstow, Susanne Craig, and Russ Buettner that was published on October 2, 2018; the Washington Post; Vanity Fair; Politico; the TWA Museum website; and Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking. For background on Steeplechase Park, I thank the Coney Island History Project website, Brooklyn Paper, and a May 14, 2018, article on 6sqft.com by Dana Schulz. -

Concerned, Meet Terrified Intersectional Feminism and the Women's March

Women's Studies International Forum 69 (2018) 49–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif Concerned, meet terrified: Intersectional feminism and the Women's March T ⁎ Sierra Brewer, Lauren Dundes Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The first US Women's March on January 21, 2017 seemingly had the potential to unite women across race. To Women's March assess the progress of feminism towards an increasingly intersectional feminist approach, the authors collected Trump and analyzed interview data from 20 young African American women who shared their impressions of the Clinton Women's March that followed Donald Trump's inauguration during the month after the march. Interviewees White feminism believed that Trump's election and his sexism spurred the march, prompting the participation of many women Intersectional feminism who had not previously embraced feminism. Interviewees suggested that the march provided white women with Pussy hat ff Race a means to protest the election rather than a way to address social injustice disproportionately a ecting lower Gender social classes and people of color. Interviewees believed that a racially inclusive feminist movement would Intersectionality remain elusive without a greater commitment to intersectional feminism. African American Introduction shaming of Latina Alicia Machado, crowned Miss Universe in 1996) (Chozick & Grynbaum, 2017). Indeed, the 2005 hot mic comment ap- “If I see that white folks are concerned, then people of color need to peared to be a principal focal point of the march for white women be terrified.” galvanized by Trump bragging that fame allowed him to be sexually In the above quotation, Women's March co-chair Tamika Mallory aggressive with women without their consent. -

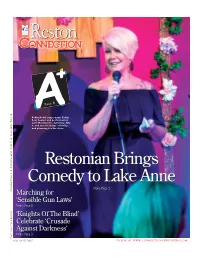

Restonreston

RestonReston Page 8 Robin Dodd (stage name Robin Rex) hosted and performed at Café Montmartre, Saturday, July 8, and was in charge of hiring and planning for the show. Classifieds, Page 10 Classifieds, ❖ RestonianRestonian BringsBrings Entertainment, Page 9 ❖ ComedyComedy toto LakeLake AnneAnne News,News, PagePage 33 Opinion, Page 4 MarchingMarching forfor ‘Sensible‘Sensible GunGun Laws’Laws’ News,News, PagePage 66 ‘Knights‘Knights OfOf TheThe Blind’Blind’ CelebrateCelebrate ‘Crusade‘Crusade AgainstAgainst Darkness’Darkness’ News,News, PagePage 33 Photo by Steve Broido www.ConnectionNewspapers.comJuly 19-25, 2017 online at www.connectionnewspapers.comReston Connection ❖ July 19-25, 2017 ❖ 1 South Lakes High School 2017 All Night Grad Party gratefully thanks our generous donors: Platinum ($500+) Emmert Family Harris Family FrozenYo Escape Room, Herndon Harvey Family Weber’s Pet Supermarket, Fox Mill Grealish Family Hawley Family Great Falls Area Ministries Hirshfeld Family Gold ($100 - 499) Hand & Stone Massage & Facial Spa Hughes Family Baser Family Harris Teeter, Spectrum Center Hunan East Restaurant Bond Family Harris Teeter, Woodland Crossing Irwin Family Chic Fil-A, Reston Jammula Family Jaeger Family Dlott Family Jersey Mike’s Subs, Reston Kanode Family Flippin’ Pizza, Reston Kalypso’s Sports Grill Karras Family Glory Days, Fox Mill & North Point Kong Family Kelly Family Golinsky Specific Chiropractic KSB Café of New York Konowe Family Greater Reston Arts Center King Pollo, Reston Kumar Family HoneyBaked Ham Lucia’s Italian Ristorante, -

Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/369 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Maxime Dafaure, « The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/369 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies 1 The “Great Meme War:” the Alt- Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Memes and the metapolitics of the alt-right 1 The alt-right has been a major actor of the online culture wars of the past few years. Since it came to prominence during the 2014 Gamergate controversy,1 this loosely- defined, puzzling movement has achieved mainstream recognition and has been the subject of discussion by journalists and scholars alike. Although the movement is notoriously difficult to define, a few overarching themes can be delineated: unequivocal rejections of immigration and multiculturalism among most, if not all, alt- right subgroups; an intense criticism of feminism, in particular within the manosphere community, which itself is divided into several clans with different goals and subcultures (men’s rights activists, Men Going Their Own Way, pick-up artists, incels).2 Demographically speaking, an overwhelming majority of alt-righters are white heterosexual males, one of the major social categories who feel dispossessed and resentful, as pointed out as early as in the mid-20th century by Daniel Bell, and more recently by Michael Kimmel (Angry White Men 2013) and Dick Howard (Les Ombres de l’Amérique 2017). -

Women's March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity

Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 0 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Originally posted on the blog of The American Prospect, January 6, 2017. Confederacy” By Laurie Green For those who believe Donald Trump’s election has further legitimized hatred and even violence, a “Women’s March on Washington” scheduled for January 21 offers an outlet to demonstrate mass solidarity across lines of race, religion, age, gender, national identity, and sexual orientation. May 06, 2020 More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (The Center for Jewish History via Flickr) The idea of such a march first ricocheted across social media just hours after the TV networks called the DIGITAL HISTORY election for Trump, when a grandmother in Hawaii suggested it to fellow Facebook friends on the private, pro-Hillary Clinton group page known as Pantsuit Nation. Millions of postings later, the D.C. march has mushroomed to include parallel events in 41 states and 21 cities outside the United States. An Más de 72: Digital Archive Review independent national organizing committee has stepped in to articulate a clear mission and take over https://notevenpast.org/womens-march-like-many-before-it-struggles-for-unity/[6/19/2020 8:58:41 AM] Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity - Not Even Past logistics.