Capuzza and Daily Capitalized on the Energy Created by the March to Achieve Their Ends (Cochrane, 2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hegemonic Masculinity and Humor in the 2016 Presidential Election

SRDXXX10.1177/2378023117749380SociusSmirnova 749380research-article2017 Special Issue: Gender & Politics Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World Volume X: 1 –16 © The Author(s) 2017 Small Hands, Nasty Women, and Bad Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Hombres: Hegemonic Masculinity and DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117749380 10.1177/2378023117749380 Humor in the 2016 Presidential Election srd.sagepub.com Michelle Smirnova1 Abstract Given that the president is thought to be the national representative, presidential campaigns often reflect the efforts to define a national identity and collective values. Political humor provides a unique lens through which to explore how identity figures into national politics given that the critique of an intended target is often made through popular cultural scripts that often inadvertently reify the very power structures they seek to subvert. In conducting an analysis of 240 tweets, memes, and political cartoons from the 2016 U.S. presidential election targeting the two frontrunners, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, we see how popular political humor often reaffirmed heteronormative assumptions of gender, sexuality, and race and equated scripts of hegemonic masculinity with presidential ability. In doing so, these discourses reified a patriarchal power structure. Keywords gender, hegemonic masculinity, memes, humor, politics Introduction by which patriarchal power subjugates or excludes women, the LGTBQ community, people of color, and other marginal- On November 8, 2016, Republican candidate Donald Trump ized populations. Hegemonic masculinity is directly linked was elected president of the United States over Democratic to patriarchy in that it exists as the form of masculinity that candidate Hillary Clinton. Gender was a particularly salient is “culturally exalted” in a particular historical and geograph- feature of the 2016 U.S. -

Donald Trump Shoots the Match1 Sharon Mazer

Donald Trump Shoots the Match1 Sharon Mazer The day I realized it can be smart to be shallow was, for me, a deep experience. —Donald J. Trump (2004; in Remnick 2017:19) I don’t care if it’s real or not. Kill him! Kill him! 2 He’s currently President of the USA, but a scant 10 years ago, Donald Trump stepped into the squared circle, facing off against WWE owner and quintessential heel Mr. McMahon3 in the “Battle of the Billionaires” (WrestleMania XXIII). The stakes were high. The loser would have his head shaved by the winner. (Spoiler alert: Trump won.) Both Trump and McMahon kept their suits on—oversized, with exceptionally long ties—in a way that made their heads appear to hover, disproportionately small, over their bulky (Trump) and bulked up (McMahon) bodies. As avatars of capitalist, patriarchal power, they left the heavy lifting to the gleamingly exposed, hypermasculinist bodies of their pro-wrestler surrogates. McMahon performed an expert heel turn: a craven villain, egging the audience to taunt him as a clueless, elitist frontman as he did the job of casting Trump as an (unlikely) babyface, the crowd’s champion. For his part, Trump seemed more mark than smart. Where McMahon and the other wrestlers were working around him, like ham actors in an outsized play, Trump was shooting the match: that is, not so much acting naturally as neglecting to act at all. He soaked up the cheers, stalked the ring, took a fall, threw a sucker punch, and claimed victory as if he (and he alone) had fought the good fight (WWE 2013b). -

Pdf, 306.71 KB

Trends Like These 242: Warren Releases Healthcare Plan, Fake Bridezilla Dramatic Reading, Richard Spencer’s True Form, Trump Owes $2M for Sham Charity, Jeffrey Epstein Autopsy Findings, Massive AirBnb Scam, Trump Jr. is Still a Jerk Published on November 8th, 2019 Listen on TheMcElroy.family Brent: This week: McDonald‘s CEO gets canned, Elizabeth Warren‘s brand new plan, and Popeye‘s we stan. Courtney: I'm Courtney Enlow. Brent: I'm Brent Black. Courtney: And I'm going to need an extra week off life! Brent: With Trends Like These. Brent: Hello, Courtney. Courtney: Hello, Brent! Brent: We are doing a show… get this, get this. And I can't stress this enough… about trending news! Courtney: What? [laughs] Oh my god. Brent: I know! Which timeline did we end up in? Courtney: It'll never catch on. Brent: Well, we‘ll give it a college try. Courtney: Yeah. Brent: Um… welcome to Trends Like These, real life friends talking internet trends. It‘s what we do. This week is a Courtney and Brent twofer. A two- hander, as you might say in the theater. Courtney: And y'know what? I actually—this episode is where we are going to introduce the Courtney and Brent theatrical players. Brent: Yes. Courtney and Brent repertory theater. Courtney: Yes. It‘s going to be a thing of beauty and joy forever. Brent: Well, at least your part. We‘ll see. Courtney: [sings] Foreverrr… Brent: I'll dust off my acting skills. Um… Courtney: Hey, Brent. Really important question. And I already know the answer, but it‘s basically like a pretend question to like, get us into like, a fun conversation. -

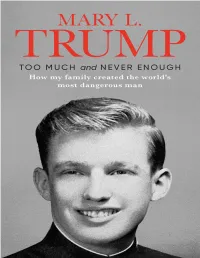

Donald Had Started Branding All of His Buildings in Manhattan, My Feelings About My Name Became More Complicated

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook. Join our mailing list to get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox. For my daughter, Avary, and my dad If the soul is left in darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but the one who causes the darkness. —Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Author’s Note Much of this book comes from my own memory. For events during which I was not present, I relied on conversations and interviews, many of which are recorded, with members of my family, family friends, neighbors, and associates. I’ve reconstructed some dialogue according to what I personally remember and what others have told me. Where dialogue appears, my intention was to re-create the essence of conversations rather than provide verbatim quotes. I have also relied on legal documents, bank statements, tax returns, private journals, family documents, correspondence, emails, texts, photographs, and other records. For general background, I relied on the New York Times, in particular the investigative article by David Barstow, Susanne Craig, and Russ Buettner that was published on October 2, 2018; the Washington Post; Vanity Fair; Politico; the TWA Museum website; and Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking. For background on Steeplechase Park, I thank the Coney Island History Project website, Brooklyn Paper, and a May 14, 2018, article on 6sqft.com by Dana Schulz. -

Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/369 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Maxime Dafaure, « The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/369 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies 1 The “Great Meme War:” the Alt- Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Memes and the metapolitics of the alt-right 1 The alt-right has been a major actor of the online culture wars of the past few years. Since it came to prominence during the 2014 Gamergate controversy,1 this loosely- defined, puzzling movement has achieved mainstream recognition and has been the subject of discussion by journalists and scholars alike. Although the movement is notoriously difficult to define, a few overarching themes can be delineated: unequivocal rejections of immigration and multiculturalism among most, if not all, alt- right subgroups; an intense criticism of feminism, in particular within the manosphere community, which itself is divided into several clans with different goals and subcultures (men’s rights activists, Men Going Their Own Way, pick-up artists, incels).2 Demographically speaking, an overwhelming majority of alt-righters are white heterosexual males, one of the major social categories who feel dispossessed and resentful, as pointed out as early as in the mid-20th century by Daniel Bell, and more recently by Michael Kimmel (Angry White Men 2013) and Dick Howard (Les Ombres de l’Amérique 2017). -

Online Appendix

Web Appendix 1 References for Appendix 1 Bakliwal, A., Foster, J., van der Puil, J., O'Brien, R., Tounsi, L., & Hughes, M. (2013, June). Sentiment analysis of political tweets: Towards an accurate classifier. Association for Computational Linguistics. Bermingham, A., & Smeaton, A. (2011). On using Twitter to monitor political sentiment and predict election results. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Sentiment Analysis where AI meets Psychology (SAAIP 2011) (pp. 2-10). Bollen, J., Mao, H., & Pepe, A. (2011). Modeling public mood and emotion: Twitter sentiment and socio-economic phenomena. Icwsm, 11, 450-453. Burnap, P., Gibson, R., Sloan, L., Southern, R., & Williams, M. (2016). 140 characters to victory?: Using Twitter to predict the UK 2015 General Election. Electoral Studies, 41, 230-233. Chin, D., Zappone, A., & Zhao, J. (2016). Analyzing Twitter sentiment of the 2016 presidential candidates. News & Publications: Stanford University. Choy, M., Cheong, M. L., Laik, M. N., & Shung, K. P. (2011). A sentiment analysis of Singapore Presidential Election 2011 using Twitter data with census correction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1108.5520. Conover, M., Ratkiewicz, J., Francisco, M. R., Gonçalves, B., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2011). Political polarization on twitter. Icwsm, 133, 89-96. Dang-Xuan, L., Stieglitz, S., Wladarsch, J., and Neuberger, C. (2013), “An investigation of influential and the role of sentiment in political communications on Twitter during election periods”, Information, Communication, and Society, 16(5), 795-825. Diakopoulos, N. A., & Shamma, D. A. (2010, April). Characterizing debate performance via aggregated twitter sentiment. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1195-1198). ACM. -

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

The Rhetoric of Feminist Hashtags and Respectability Politics

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Spring 2018 Are We All #NastyWomen? The Rhetoric of Feminist Hashtags and Respectability Politics Kimberly Lynette Goode Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Goode, Kimberly L.. "Are We All #NastyWomen? The Rhetoric of Feminist Hashtags and Respectability Politics" (2018). Master of Arts (MA), Thesis, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/6bj5-7f60 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARE WE ALL #NASTYWOMEN? THE RHETORIC OF FEMINIST HASHTAGS AND RESPECTABILITY POLITICS by Kimberly Lynette Goode B.S. August 2015, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS ENGLISH OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2018 Approved by: Candace Epps-Robertson (Director) Julia Romberger (Member) Avi Santo (Member) ABSTRACT ARE WE ALL #NASTYWOMEN? THE RHETORIC OF FEMINIST HASHTAGS AND RESPECTABILITY POLITICS Kimberly Lynette Goode Old Dominion University, 2018 Director: Dr. Candace Epps-Robertson In a time where misogynistic phrases from political figures such as Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell are being reclaimed by feminists on Twitter, it is crucial for feminist rhetorical scholars to pay close attention to the rhetorical dynamics of such reclamation efforts. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 5, 2017 No. 160 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was for work could often seem bleak. For check, helping businesses grow and called to order by the President pro those men and women, the promise of a workers succeed, helping move the tempore (Mr. HATCH). hard-earned retirement seemed to drift economy into high gear so we can sus- f further and further away. For so many tain real prosperity into the future for middle-class Americans, the last dec- America’s middle class. PRAYER ade meant a weak economy and a de- These are the kinds of ideas that The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- cline of opportunities. People of this should be shared by everyone, Repub- fered the following prayer: Nation deserve better. They deserve licans and Democrats alike. Our friends Let us pray. larger paychecks, more jobs, and better across the aisle supported the need for Father of love, who made Heaven and opportunities to get ahead. tax reform for many years. They used Earth, sustain us through this day. This Congress is committed to help- to advocate it loudly. But the tone May our lawmakers focus on Your ing the economy live up to its full po- seems to be different now. What glory and not their own. Inspire them tential once again, which is exactly changed? The President, or so it would with Your presence so that their lives why we are committed to passing tax seem. -

California Women's March Posters and Ephemera, 2017

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c89029hh No online items Guide to the California Women's March posters and ephemera, 2017 Finding Aid Authors: Laura O'Hara, project archivist, with assistance from San Francisco State University (SFSU) students Elizabeth Beutel, Margaret Paz, and Alesha Marie Sohler. © Copyright 2019 Sutro Library, California State Library. All rights reserved. 1630 Holloway Avenue 5th floor San Francisco, CA, 94132-4030 URL: http://www.library.ca.gov/about/sutro_main.html Email: [email protected] Phone: 415-469-6100 Guide to the California Women's M000014 1 March posters and ephemera, 2017 Guide to the California Women's March posters and ephemera, 2017 2017 Sutro Library, California State Library Overview of the Collection Collection Title: California Women's March posters and ephemera, 2017 Identification: M000014 Creator: Sutro Library Staff Language of Materials: English Repository: Sutro Library, California State Library 1630 Holloway Avenue 5th floor San Francisco, CA, 94132-4030 URL: http://www.library.ca.gov/about/sutro_main.html Email: [email protected] Phone: 415-469-6100 Abstract: The bulk of this collection consists of 288 posters collected from various Women’s Marches in California, plus some ephemera and artifacts that accompanied or supplements the posters. The ephemera includes testimonials, photographs, and media coverage. The artifacts include pussy hats, sashes, and pin-back buttons. The marches represented took place in Albany, Chico, Los Angeles, Oakland, Oakland, Sacramento, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, and Santa Rosa; Californians also marched in Washington, DC. Administrative History: The Women's March was a worldwide protest that happened on January 21, 2017. -

“Nasty” Woman and “Very Happy Young Girl”: the Political Culture of Women in Donald Trump’S America

Western New England Law Review Volume 42 42 Issue 3 Article 2 2020 “NASTY” WOMAN AND “VERY HAPPY YOUNG GIRL”: THE POLITICAL CULTURE OF WOMEN IN DONALD TRUMP’S AMERICA John Baick Western New England University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation John Baick, “NASTY” WOMAN AND “VERY HAPPY YOUNG GIRL”: THE POLITICAL CULTURE OF WOMEN IN DONALD TRUMP’S AMERICA, 42 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 341 (2020), https://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/ lawreview/vol42/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Review & Student Publications at Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western New England Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW Volume 42 2020 Issue 3 “NASTY”1 WOMAN AND “VERY HAPPY YOUNG GIRL”2: THE POLITICAL CULTURE OF WOMEN IN DONALD TRUMP’S AMERICA JOHN BAICK* Discussions of gender and politics in the present day must include a consideration of the charged atmosphere of our political culture. Americans were embroiled in culture wars for much of the twentieth century—conflicts that included the right of women to vote, the civil rights of African Americans and other minority groups, and the meaning of sexuality. New debates have been added in the last few years—many of which center on gender, sexuality, and race. The culture wars have reached a fevered peak with the election and administration of Donald Trump. -

Theatre Centre - Franco Boni

JULY 5–16, 2017 FREE PROGRAM Julianna Romanyk, Fringe Volunteer Julianna Romanyk, FRINGETORONTO.COM SHAKESPEARE IN HIGH PARK 35t H ANNIVERSARY .com king lear + twelfth night BY William Shakespeare KING LEAR DIRECTED BY Alistair Newton TWELFTH NIGHT DIRECTED BY Tanja Jacobs FEATURING Diane D’Aquila AS LEAR “A must-see summer AttrAction in toronto” - THE GLOBE AND MAIL PAY TUE - SUN @ 8PM WHAT HiGH PArK AmPHitHeAtre YOU CAN or reServe oNliNe Jun 29 – seP 3 A CANADIAN STAGE PRODUCTION IN COLLABORATION WITH THE DEPARTMENT OFTHEATRE IN THE SCHOOL OF THE ARTS, MEDIA, PERFORMANCE & DESIGN AT YORK UNIVERSITY WELCOME TO THE FRINGE! A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Welcome to the 29th annual Toronto Fringe Festival! We are Ontario’s largest theatre festival, welcoming 160 companies and over 1,200 artists from all around the world. This year our Fringe Club migrates south on Bathurst to the Scadding Court Community Centre. Located on the south-east corner of Bathurst and Dundas, in the heart of Fringe Festival country, this outdoor urban playground features daily activities, food vendors, concerts and more. See page 11 for all the Fringe Club details. This is also the inaugural year of our Teen Fringe program with our partners at Scadding Court Community Centre and Edge of Sky Productions. Teen Fringe is a performance intensive that welcomes teens from across the GTA to train with leading professionals in acting, singing and dancing. Don’t miss the big performance when the teens take to the stage as part of the closing night show of True North Mix Tape.