Hegemonic Masculinity and Humor in the 2016 Presidential Election

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donald Trump Shoots the Match1 Sharon Mazer

Donald Trump Shoots the Match1 Sharon Mazer The day I realized it can be smart to be shallow was, for me, a deep experience. —Donald J. Trump (2004; in Remnick 2017:19) I don’t care if it’s real or not. Kill him! Kill him! 2 He’s currently President of the USA, but a scant 10 years ago, Donald Trump stepped into the squared circle, facing off against WWE owner and quintessential heel Mr. McMahon3 in the “Battle of the Billionaires” (WrestleMania XXIII). The stakes were high. The loser would have his head shaved by the winner. (Spoiler alert: Trump won.) Both Trump and McMahon kept their suits on—oversized, with exceptionally long ties—in a way that made their heads appear to hover, disproportionately small, over their bulky (Trump) and bulked up (McMahon) bodies. As avatars of capitalist, patriarchal power, they left the heavy lifting to the gleamingly exposed, hypermasculinist bodies of their pro-wrestler surrogates. McMahon performed an expert heel turn: a craven villain, egging the audience to taunt him as a clueless, elitist frontman as he did the job of casting Trump as an (unlikely) babyface, the crowd’s champion. For his part, Trump seemed more mark than smart. Where McMahon and the other wrestlers were working around him, like ham actors in an outsized play, Trump was shooting the match: that is, not so much acting naturally as neglecting to act at all. He soaked up the cheers, stalked the ring, took a fall, threw a sucker punch, and claimed victory as if he (and he alone) had fought the good fight (WWE 2013b). -

Capuzza and Daily Capitalized on the Energy Created by the March to Achieve Their Ends (Cochrane, 2017)

Women & Language We March On: Voices from the Women’s March on Washington Jamie C. Capuzza University of Mount Union Tamara Daily University of Mount Union Abstract: Protest marches are an important means of political expression. We investigated protesters’ motives for participating in the original Women’s March on Washington. Two research questions guided this study. First, to what degree did concerns about gender injustices motivate marchers to participate? Second, to what degree did marchers’ motives align with the goals established by march organizers? Seven-hundred eighty-seven participants responded to three open-ended questions: (1) Why did you choose to participate in the march, (2) What did you hope to accomplish, and (3) What events during the 2016 presidential election caused you the greatest concern? Responses were coded thematically. Findings indicated that gender injustices were not the sole source of motivation. Most respondents were motivated to march for a variety of reasons, hoped the march would function as a show of solidarity and resistance, and indicated that the misogynistic rhetoric of the 2016 presidential campaign was a deep concern. Finally, the comparison of respondents’ motives and organizers’ stated goals indicated a shared sense of purpose for the march. Keywords:feminism, Women’s March, political communication, motive, intersectionality ON JANUARY 21, 2017, AN ESTIMATED seven million people joined together across all seven continents in one of the largest political protests the world has witnessed. The Women’s March on Washington, including its over 650 sister marches, is considered the largest of its kind in U.S. history (Chenoweth & Pressman, 2017; Wallace & Parlapiano, 2017), and it is one of the most significant political and rhetorical events of the contemporary women’s movement. -

Introduction

Introduction Philip E. Steinberg In the weeks leading up to the 2016 US presidential election, Political Geography received two unsolicited guest editorials opining on the surging popularity of Donald Trump and, more broadly, the movement that he represented. In one editorial, Banu Gökariksel and Sara Smith associated the Trump phenomenon with the reassertion of a masculinist politics wherein the violent, white, male body is seen as the normative political figure. In the other, Sam Page and Jason Dittmer also focused on the embodied nature of Trump’s popularity, but they locate this in a complicated system in which oppositional tendencies also have momentum, and thus they end their editorial with a fairly optimistic assertion about the ways in which the openings made possible by Trump might lead to a counter-revolution of sorts, wherein the antinomies that increasingly characterise politics in the United States (and elsewhere) are overthrown. After the election, we received two more unsolicited guest editorials reflecting on the topic. In one, Alan Ingram paired the Trump election with Brexit referendum that had been held five months earlier, and places both within an analytical framework inspired by the Deleuzian concept of the ‘machine’. In the second editorial, Natalie Koch took a step back from the election to avert her gaze away from Trump and toward the ways in which critical pundits and scholars were understanding Trump as bringing ‘authoritarianism’ to the United States. While Koch did not necessarily disagree with the analysis of Trump’s rule as ‘authoritarian’ she noted how surprise about his popularity was rooted in a lingering American exceptionalism that clouded the analysis of the left and well as the right. -

Pdf, 306.71 KB

Trends Like These 242: Warren Releases Healthcare Plan, Fake Bridezilla Dramatic Reading, Richard Spencer’s True Form, Trump Owes $2M for Sham Charity, Jeffrey Epstein Autopsy Findings, Massive AirBnb Scam, Trump Jr. is Still a Jerk Published on November 8th, 2019 Listen on TheMcElroy.family Brent: This week: McDonald‘s CEO gets canned, Elizabeth Warren‘s brand new plan, and Popeye‘s we stan. Courtney: I'm Courtney Enlow. Brent: I'm Brent Black. Courtney: And I'm going to need an extra week off life! Brent: With Trends Like These. Brent: Hello, Courtney. Courtney: Hello, Brent! Brent: We are doing a show… get this, get this. And I can't stress this enough… about trending news! Courtney: What? [laughs] Oh my god. Brent: I know! Which timeline did we end up in? Courtney: It'll never catch on. Brent: Well, we‘ll give it a college try. Courtney: Yeah. Brent: Um… welcome to Trends Like These, real life friends talking internet trends. It‘s what we do. This week is a Courtney and Brent twofer. A two- hander, as you might say in the theater. Courtney: And y'know what? I actually—this episode is where we are going to introduce the Courtney and Brent theatrical players. Brent: Yes. Courtney and Brent repertory theater. Courtney: Yes. It‘s going to be a thing of beauty and joy forever. Brent: Well, at least your part. We‘ll see. Courtney: [sings] Foreverrr… Brent: I'll dust off my acting skills. Um… Courtney: Hey, Brent. Really important question. And I already know the answer, but it‘s basically like a pretend question to like, get us into like, a fun conversation. -

Donald Had Started Branding All of His Buildings in Manhattan, My Feelings About My Name Became More Complicated

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook. Join our mailing list to get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox. For my daughter, Avary, and my dad If the soul is left in darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but the one who causes the darkness. —Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Author’s Note Much of this book comes from my own memory. For events during which I was not present, I relied on conversations and interviews, many of which are recorded, with members of my family, family friends, neighbors, and associates. I’ve reconstructed some dialogue according to what I personally remember and what others have told me. Where dialogue appears, my intention was to re-create the essence of conversations rather than provide verbatim quotes. I have also relied on legal documents, bank statements, tax returns, private journals, family documents, correspondence, emails, texts, photographs, and other records. For general background, I relied on the New York Times, in particular the investigative article by David Barstow, Susanne Craig, and Russ Buettner that was published on October 2, 2018; the Washington Post; Vanity Fair; Politico; the TWA Museum website; and Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking. For background on Steeplechase Park, I thank the Coney Island History Project website, Brooklyn Paper, and a May 14, 2018, article on 6sqft.com by Dana Schulz. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/369 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Maxime Dafaure, « The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/369 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies 1 The “Great Meme War:” the Alt- Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Memes and the metapolitics of the alt-right 1 The alt-right has been a major actor of the online culture wars of the past few years. Since it came to prominence during the 2014 Gamergate controversy,1 this loosely- defined, puzzling movement has achieved mainstream recognition and has been the subject of discussion by journalists and scholars alike. Although the movement is notoriously difficult to define, a few overarching themes can be delineated: unequivocal rejections of immigration and multiculturalism among most, if not all, alt- right subgroups; an intense criticism of feminism, in particular within the manosphere community, which itself is divided into several clans with different goals and subcultures (men’s rights activists, Men Going Their Own Way, pick-up artists, incels).2 Demographically speaking, an overwhelming majority of alt-righters are white heterosexual males, one of the major social categories who feel dispossessed and resentful, as pointed out as early as in the mid-20th century by Daniel Bell, and more recently by Michael Kimmel (Angry White Men 2013) and Dick Howard (Les Ombres de l’Amérique 2017). -

Online Appendix

Web Appendix 1 References for Appendix 1 Bakliwal, A., Foster, J., van der Puil, J., O'Brien, R., Tounsi, L., & Hughes, M. (2013, June). Sentiment analysis of political tweets: Towards an accurate classifier. Association for Computational Linguistics. Bermingham, A., & Smeaton, A. (2011). On using Twitter to monitor political sentiment and predict election results. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Sentiment Analysis where AI meets Psychology (SAAIP 2011) (pp. 2-10). Bollen, J., Mao, H., & Pepe, A. (2011). Modeling public mood and emotion: Twitter sentiment and socio-economic phenomena. Icwsm, 11, 450-453. Burnap, P., Gibson, R., Sloan, L., Southern, R., & Williams, M. (2016). 140 characters to victory?: Using Twitter to predict the UK 2015 General Election. Electoral Studies, 41, 230-233. Chin, D., Zappone, A., & Zhao, J. (2016). Analyzing Twitter sentiment of the 2016 presidential candidates. News & Publications: Stanford University. Choy, M., Cheong, M. L., Laik, M. N., & Shung, K. P. (2011). A sentiment analysis of Singapore Presidential Election 2011 using Twitter data with census correction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1108.5520. Conover, M., Ratkiewicz, J., Francisco, M. R., Gonçalves, B., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2011). Political polarization on twitter. Icwsm, 133, 89-96. Dang-Xuan, L., Stieglitz, S., Wladarsch, J., and Neuberger, C. (2013), “An investigation of influential and the role of sentiment in political communications on Twitter during election periods”, Information, Communication, and Society, 16(5), 795-825. Diakopoulos, N. A., & Shamma, D. A. (2010, April). Characterizing debate performance via aggregated twitter sentiment. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1195-1198). ACM. -

Escaping Eden

Escaping Eden Chapter 1 I wake up screaming. Where am I? What’s going on? Why do I feel so cold? It’s dark. I look around, blinking sleep from my eyes. I notice a window somewhere in the back of the room. It’s open and moonlight shines through, casting a square beam of light across the floor. A breeze drifts in, and white curtains float like pale ghosts in the darkness. In the narrow light of the moon, I see that the carpet is burgundy. I also see the outlines of furniture. My head vaguely aching, I look at the shadows scattered messily across the room. I feel like sweeping them up to make room for light. I shake off the urge. Stop being delusional. There’s a funny smell in the air, like a mixture of old home mustiness and laboratory sterilization. I realize that I’m lying on the floor. Why am I not on the bed? The last thing I remember is pain. Maybe that’s why I woke up screaming. The pain was intense. The pain was… cold. I decide to swallow my fear. It tastes terrible. I stand up and my neck aches. As I rub my hand across it, my bones crack like I haven’t moved in a long time. I whisper to myself. “As Grandpa always said…” My train of thought rolls off into the distance. Where was I going with this? Who is “Grandpa”? I put my hand on my sweaty forehead. I must be tired. I look for a light switch by approaching the walls and groping around. -

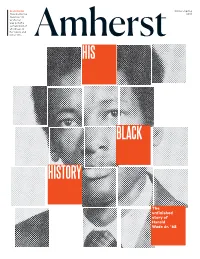

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

(CUWS) Outreach Journal #1283

Issue No. 1283 29 September 2017 // USAFCUWS Outreach Journal Issue 1283 // 29 Sept 2017 CUWS Outreach Journal Featured Item: “Strengthening the Counter-Illicit Nuclear Trade Regime in the Face of New Threats: A Two-Year Review of Proliferation Threats Associated with the Middle East”. Written by David Albright, Andrea Stricker, Sarah Burkhard and Erica Wenig, published by the Institute for Science and International Security; September 12, 2017 http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis- reports/documents/Final_Policy_Report_Threats_to_Counter_Illicit_Trade_Regime_12Sept2017_Final.p df The United States’ and associated global export control regime is losing ground due to several global events and trends underway in the United States and the Middle East. The developments at home and abroad are reducing controls and oversight over the flow of commodities vital to the development of nuclear weapons. Unless these trends are reversed, U.S. efforts to stem and stop nuclear proliferation in the Middle East and elsewhere will weaken. Events contributing to this greater proliferation danger include: 1) relaxed U.S. export control regulations and greater emphasis on global trade with streamlined exchange of intellectual property and commodities, including nuclear commodities; 2) on-going questions over the strong regulation of sensitive trade to Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs; and 3) the expected actions of additional states to obtain nuclear capabilities to counterbalance Iran. This report provides findings from four studies that were part of a two-year Institute for Science and International Security review which identified threats to the United States’ and interconnected global export control regime and actions to take now to mitigate damages. The review found that U.S. -

The Gender of Trumpism

MCS – Masculinities and Social Change Vol. 6 No. 2 June 2017 pp. 119-141 Who is a Real Man? The Gender of Trumpism C. J. Pascoe University of Oregon Abstract The rise of Trumpism exemplifies a contest over masculinity, over who qualifies as a “real man.” This contest being waged not only by some obvious actors – President Trump, his supporters and representatives; it is a contest also waged by those who oppose the current administration and are perhaps actively working against the perpetuation of gender inequality. The themes deployed by Trumpists and anti-Trumpists alike address a core component of masculinity in the global west – dominance. Through sexualized processes of confirmation and repudiation multiple actors in this political and social moment draw on and deploy understandings of normative masculinity as dominance – dominance over women and dominance over other, less masculine, men. Both the Trumpist and anti- Trumpist movements exemplify similar discourses of masculinized dominance in which social actors claim masculinity through discourses and symbols of “compulsive heterosexuality” and divest others of it through the emasculating practices of a “fag discourse.” The story of Trumpism and movements against it is an example of the tenacity of inequality in gendered discourses. Keywords: masculinity, sexism, homophobia, Trump, politics 2017 Hipatia Press ISSN: 2014-3605 DOI: 10.17583/MCS.2017.2745 MCS – Masculinities and Social Change Vol. 6 No. 2 June 2017 pp. 119-141 ¿Quién es un Hombre Real? El Género del Trumpism C. J. Pascoe University of Oregon Resumen El auge del Trumpism ejemplifica un concurso sobre la masculinidad, sobre quién es realmente un "hombre verdadero." Este concurso está liderado por algunos actores obvios – el presidente Trump, sus partidarios y representantes.