GENDER STUDIES Chapter Showcase | 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hegemonic Masculinity and Humor in the 2016 Presidential Election

SRDXXX10.1177/2378023117749380SociusSmirnova 749380research-article2017 Special Issue: Gender & Politics Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World Volume X: 1 –16 © The Author(s) 2017 Small Hands, Nasty Women, and Bad Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Hombres: Hegemonic Masculinity and DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117749380 10.1177/2378023117749380 Humor in the 2016 Presidential Election srd.sagepub.com Michelle Smirnova1 Abstract Given that the president is thought to be the national representative, presidential campaigns often reflect the efforts to define a national identity and collective values. Political humor provides a unique lens through which to explore how identity figures into national politics given that the critique of an intended target is often made through popular cultural scripts that often inadvertently reify the very power structures they seek to subvert. In conducting an analysis of 240 tweets, memes, and political cartoons from the 2016 U.S. presidential election targeting the two frontrunners, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, we see how popular political humor often reaffirmed heteronormative assumptions of gender, sexuality, and race and equated scripts of hegemonic masculinity with presidential ability. In doing so, these discourses reified a patriarchal power structure. Keywords gender, hegemonic masculinity, memes, humor, politics Introduction by which patriarchal power subjugates or excludes women, the LGTBQ community, people of color, and other marginal- On November 8, 2016, Republican candidate Donald Trump ized populations. Hegemonic masculinity is directly linked was elected president of the United States over Democratic to patriarchy in that it exists as the form of masculinity that candidate Hillary Clinton. Gender was a particularly salient is “culturally exalted” in a particular historical and geograph- feature of the 2016 U.S. -

Donald Trump Shoots the Match1 Sharon Mazer

Donald Trump Shoots the Match1 Sharon Mazer The day I realized it can be smart to be shallow was, for me, a deep experience. —Donald J. Trump (2004; in Remnick 2017:19) I don’t care if it’s real or not. Kill him! Kill him! 2 He’s currently President of the USA, but a scant 10 years ago, Donald Trump stepped into the squared circle, facing off against WWE owner and quintessential heel Mr. McMahon3 in the “Battle of the Billionaires” (WrestleMania XXIII). The stakes were high. The loser would have his head shaved by the winner. (Spoiler alert: Trump won.) Both Trump and McMahon kept their suits on—oversized, with exceptionally long ties—in a way that made their heads appear to hover, disproportionately small, over their bulky (Trump) and bulked up (McMahon) bodies. As avatars of capitalist, patriarchal power, they left the heavy lifting to the gleamingly exposed, hypermasculinist bodies of their pro-wrestler surrogates. McMahon performed an expert heel turn: a craven villain, egging the audience to taunt him as a clueless, elitist frontman as he did the job of casting Trump as an (unlikely) babyface, the crowd’s champion. For his part, Trump seemed more mark than smart. Where McMahon and the other wrestlers were working around him, like ham actors in an outsized play, Trump was shooting the match: that is, not so much acting naturally as neglecting to act at all. He soaked up the cheers, stalked the ring, took a fall, threw a sucker punch, and claimed victory as if he (and he alone) had fought the good fight (WWE 2013b). -

Capuzza and Daily Capitalized on the Energy Created by the March to Achieve Their Ends (Cochrane, 2017)

Women & Language We March On: Voices from the Women’s March on Washington Jamie C. Capuzza University of Mount Union Tamara Daily University of Mount Union Abstract: Protest marches are an important means of political expression. We investigated protesters’ motives for participating in the original Women’s March on Washington. Two research questions guided this study. First, to what degree did concerns about gender injustices motivate marchers to participate? Second, to what degree did marchers’ motives align with the goals established by march organizers? Seven-hundred eighty-seven participants responded to three open-ended questions: (1) Why did you choose to participate in the march, (2) What did you hope to accomplish, and (3) What events during the 2016 presidential election caused you the greatest concern? Responses were coded thematically. Findings indicated that gender injustices were not the sole source of motivation. Most respondents were motivated to march for a variety of reasons, hoped the march would function as a show of solidarity and resistance, and indicated that the misogynistic rhetoric of the 2016 presidential campaign was a deep concern. Finally, the comparison of respondents’ motives and organizers’ stated goals indicated a shared sense of purpose for the march. Keywords:feminism, Women’s March, political communication, motive, intersectionality ON JANUARY 21, 2017, AN ESTIMATED seven million people joined together across all seven continents in one of the largest political protests the world has witnessed. The Women’s March on Washington, including its over 650 sister marches, is considered the largest of its kind in U.S. history (Chenoweth & Pressman, 2017; Wallace & Parlapiano, 2017), and it is one of the most significant political and rhetorical events of the contemporary women’s movement. -

Pdf, 306.71 KB

Trends Like These 242: Warren Releases Healthcare Plan, Fake Bridezilla Dramatic Reading, Richard Spencer’s True Form, Trump Owes $2M for Sham Charity, Jeffrey Epstein Autopsy Findings, Massive AirBnb Scam, Trump Jr. is Still a Jerk Published on November 8th, 2019 Listen on TheMcElroy.family Brent: This week: McDonald‘s CEO gets canned, Elizabeth Warren‘s brand new plan, and Popeye‘s we stan. Courtney: I'm Courtney Enlow. Brent: I'm Brent Black. Courtney: And I'm going to need an extra week off life! Brent: With Trends Like These. Brent: Hello, Courtney. Courtney: Hello, Brent! Brent: We are doing a show… get this, get this. And I can't stress this enough… about trending news! Courtney: What? [laughs] Oh my god. Brent: I know! Which timeline did we end up in? Courtney: It'll never catch on. Brent: Well, we‘ll give it a college try. Courtney: Yeah. Brent: Um… welcome to Trends Like These, real life friends talking internet trends. It‘s what we do. This week is a Courtney and Brent twofer. A two- hander, as you might say in the theater. Courtney: And y'know what? I actually—this episode is where we are going to introduce the Courtney and Brent theatrical players. Brent: Yes. Courtney and Brent repertory theater. Courtney: Yes. It‘s going to be a thing of beauty and joy forever. Brent: Well, at least your part. We‘ll see. Courtney: [sings] Foreverrr… Brent: I'll dust off my acting skills. Um… Courtney: Hey, Brent. Really important question. And I already know the answer, but it‘s basically like a pretend question to like, get us into like, a fun conversation. -

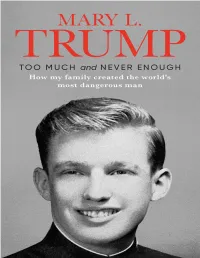

Donald Had Started Branding All of His Buildings in Manhattan, My Feelings About My Name Became More Complicated

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook. Join our mailing list to get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox. For my daughter, Avary, and my dad If the soul is left in darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but the one who causes the darkness. —Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Author’s Note Much of this book comes from my own memory. For events during which I was not present, I relied on conversations and interviews, many of which are recorded, with members of my family, family friends, neighbors, and associates. I’ve reconstructed some dialogue according to what I personally remember and what others have told me. Where dialogue appears, my intention was to re-create the essence of conversations rather than provide verbatim quotes. I have also relied on legal documents, bank statements, tax returns, private journals, family documents, correspondence, emails, texts, photographs, and other records. For general background, I relied on the New York Times, in particular the investigative article by David Barstow, Susanne Craig, and Russ Buettner that was published on October 2, 2018; the Washington Post; Vanity Fair; Politico; the TWA Museum website; and Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking. For background on Steeplechase Park, I thank the Coney Island History Project website, Brooklyn Paper, and a May 14, 2018, article on 6sqft.com by Dana Schulz. -

In Defence of Humanity: WOMEN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS and the STRUGGLE AGAINST SILENCING in Defence of Humanity in Defence of Humanity

In Defence of Humanity: WOMEN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS AND THE STRUGGLE AGAINST SILENCING In Defence of Humanity In Defence of Humanity The lack of access to justice and resources, together with the failure of states to provide protection for Executive summary WHRDs, affects the work of WHRDs around the world. Accordingly, WHRDs need appropriate protection that is flexible to their needs. However, very little is done to respond to threats that WHRDs receive, In recent years, combined with existing threats, the rise of right-wing and nationalist populism across the and often, as Front Line Defenders reports, killings are preceded by receipt of a threat.1 This means that world has led to an increasing number of governments implementing repressive measures against the protection mechanisms need to focus too on prevention of harm by perpetrators to ensure that the right to space for civil society (civic space), particularly affecting women human rights defenders (WHRDs). The life is upheld for WHRDs and take seriously the threats that they receive. Despite efforts to implement the increasingly restricted space for WHRDs presents an urgent threat, not only to women-led organisations, Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the United Nations but to all efforts campaigning for women’s rights, gender equality and the rights of all people. In spite of (UN) Declaration on Human Rights Defenders and the Maputo Protocol - which calls for “corrective and these restrictions, WHRDs have campaigned boldly in the face of mounting opposition: movements such positive” actions where women continue to face discrimination - WHRDs still operate in dangerous contexts as #MeToo #MenAreTrash, #FreeSaudiWomen, #NiUnaMenos, #NotYourAsianSideKick and #AbortoLegalYa and are at risk of being targeted or killed. -

Forced Marriage: Children and Young People's Policy

Forced Marriage: Children and young people’s policy Date Approved: February 2019 Review date: February 2020 1 Important Note This protocol should be read in conjunction with the Pan Bedfordshire Forced Marriage and HBV Strategy -: Link trix please could a link be added here to the customers local resource area so they can add these here as they haven’t provided these documents. 2 Luton Forced Marriage: Children and young people’s protocol Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Contents 3-4 1. PURPOSE OF THE PROTOCOL ...................................................................................................................... 5 2. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 The Basis of the Protocol .............................................................................................................. 5 2.2. The Distinction between a Forced Marriage and an Arranged Marriage ...................................... 6 2.3 The “One Chance” Rule ................................................................................................................ 6 2.4 Forced Marriage and Child Abuse / Child Protection .................................................................... 6 2.5 Motivating Factors behind Forced Marriage................................................................................. -

Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy Volume 21, Number 2 Spring 2010 © 2010 by the Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law, Inc

Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy Volume 21, Number 2 Spring 2010 © 2010 by The Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law, Inc. The Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy logo © 1989 Madison James Publishing Corp., Denver, Colorado ISSN: 1050-0391 Subscriptions Personal Institutional Single Issue $15.00 $25.00 Entire Volume with Yearbook $25.00 $45.00 Payable in US currency or equivalent only. Check should accompany order. Please add $5 per single issue for postage and $15 per volume for overseas postage. All correspondence regarding subscriptions should be addressed to: Managing Editor Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy University of Colorado Law School Campus Box 401 Boulder, CO 80309-0401 - USA Manuscripts The Journal invites submission of manuscripts to be considered for publication. Manuscripts may be mailed to the address below or e-mailed directly to [email protected]. Unsolicited manuscripts can be returned if accompanied by postage and handling fees of $3.00 for 3rd class or $5.00 for 1st class mail. Manuscripts should be sent to: Lead Articles Editor Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy University of Colorado Law School Campus Box 401 Boulder, CO 80309-0401 - USA E-mail: [email protected] Internet Site: http://www.colorado.edu/law/cjielp/ Statement of Purpose and Editorial Policy The Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy is an interdisciplinary journal dedicated to the examination of environmental issues with international implications. It provides a forum for: (1) in-depth analysis of the legal or public policy implications of problems related to the global environment; (2) articulation and examination of proposals and new ideas for the management and resolution of international environmental concerns; and (3) description of current developments and opinions related to international environmental law and policy. -

Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/369 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Maxime Dafaure, « The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/369 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies 1 The “Great Meme War:” the Alt- Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Memes and the metapolitics of the alt-right 1 The alt-right has been a major actor of the online culture wars of the past few years. Since it came to prominence during the 2014 Gamergate controversy,1 this loosely- defined, puzzling movement has achieved mainstream recognition and has been the subject of discussion by journalists and scholars alike. Although the movement is notoriously difficult to define, a few overarching themes can be delineated: unequivocal rejections of immigration and multiculturalism among most, if not all, alt- right subgroups; an intense criticism of feminism, in particular within the manosphere community, which itself is divided into several clans with different goals and subcultures (men’s rights activists, Men Going Their Own Way, pick-up artists, incels).2 Demographically speaking, an overwhelming majority of alt-righters are white heterosexual males, one of the major social categories who feel dispossessed and resentful, as pointed out as early as in the mid-20th century by Daniel Bell, and more recently by Michael Kimmel (Angry White Men 2013) and Dick Howard (Les Ombres de l’Amérique 2017). -

Research Guide Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) Genealogical & Historical Records

1 UTAH VALLEY REGIONAL FAMILY HISTORY CENTER BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY HAROLD B. LEE LIBRARY RESEARCH GUIDE RELIGIOUS SOCIETY OF FRIENDS (QUAKERS) GENEALOGICAL & HISTORICAL RECORDS "The Society of Friends is a religious community. It exists in order to worship God and to witness those insights (whether on issues of peace, race relations, social justice, or whatever else) which it has found through its experience of corporate search. The Society has throughout its history sought to be meticulous in the keeping of records (whatever shortcomings there may have been in practice) and recognizes that it stands as trustee in relation to those records. The Society is not, as such, interested in genealogy, though many of its members over the years have found it an absorbing subject. There are many applications of the words of Isaiah {51:1}: "Hearken to me, ye that follow after righteousness, ye that seek the Lord; look unto the rock from whence ye are hewn and to the hole of the pit whence ye are digged. " 'Etfwan[ j{. Mi(figan & M.afco[m J. fJfwmas, ff My JInastors were Q;JaIWs, :;{ow can I jinamore about tfiem?I1, ?Jie Sodety of (jeneafogists, Lonaon, 1983: :;{tBLL 'BX7676.2 %55. "I always think of my ancestors as now living, which I believe they are. In fact I have had sufficient proof of it to dispel any doubts which could come up in my mind... My parents and grandparents knew these facts of spiritual life; I grew up in it. I could write a book about it, if I should take the time; but only a few would believe it. -

Online Appendix

Web Appendix 1 References for Appendix 1 Bakliwal, A., Foster, J., van der Puil, J., O'Brien, R., Tounsi, L., & Hughes, M. (2013, June). Sentiment analysis of political tweets: Towards an accurate classifier. Association for Computational Linguistics. Bermingham, A., & Smeaton, A. (2011). On using Twitter to monitor political sentiment and predict election results. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Sentiment Analysis where AI meets Psychology (SAAIP 2011) (pp. 2-10). Bollen, J., Mao, H., & Pepe, A. (2011). Modeling public mood and emotion: Twitter sentiment and socio-economic phenomena. Icwsm, 11, 450-453. Burnap, P., Gibson, R., Sloan, L., Southern, R., & Williams, M. (2016). 140 characters to victory?: Using Twitter to predict the UK 2015 General Election. Electoral Studies, 41, 230-233. Chin, D., Zappone, A., & Zhao, J. (2016). Analyzing Twitter sentiment of the 2016 presidential candidates. News & Publications: Stanford University. Choy, M., Cheong, M. L., Laik, M. N., & Shung, K. P. (2011). A sentiment analysis of Singapore Presidential Election 2011 using Twitter data with census correction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1108.5520. Conover, M., Ratkiewicz, J., Francisco, M. R., Gonçalves, B., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2011). Political polarization on twitter. Icwsm, 133, 89-96. Dang-Xuan, L., Stieglitz, S., Wladarsch, J., and Neuberger, C. (2013), “An investigation of influential and the role of sentiment in political communications on Twitter during election periods”, Information, Communication, and Society, 16(5), 795-825. Diakopoulos, N. A., & Shamma, D. A. (2010, April). Characterizing debate performance via aggregated twitter sentiment. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1195-1198). ACM. -

J9-Information-Pack-2019.Pdf

Introduction Background The J9 Domestic Abuse Initiative is named in memory of Janine Mundy, who was killed by her estranged husband while he was on police bail. The initiative was started by her family and the local police in Cambourne, Cornwall, where she lived and aims to raise awareness of domestic abuse and assist victims to seek the help they so desperately need. In Essex, the initiative was started by Epping Forest District Council. It expanded to Harlow and Uttlesford soon afterwards. Training is now available across the county and a list of Community Safety Partnerships delivering J9 training is available in this handout pack. Training The training sessions are intended to raise awareness and increase knowledge and understanding of domestic abuse for staff in public and voluntary sector organisations. In the course of their work, these staff may come into contact with someone they suspect is a victim of domestic abuse, or a client may reveal that they are suffering abuse. The training aims to ensure that staff are equipped to respond appropriately and effectively. Following attendance at a J9 training session, attendees will be given a J9 window sticker and organisations are asked to display the logo in their premises so that victims know where they can obtain information which will help them to access the support they need. All attendees will be provided with a J9 lanyard or pin badge. Information Pack This information pack is intended to be used to ‘signpost’ victims of domestic abuse to the support services they need. The information packs can be downloaded from: www.setdab.org/j9-initiative The SETDAB website and central mailing list of people who have been though the training is maintained by Southend, Essex and Thurrock Domestic Abuse Partnership.