Concerned, Meet Terrified Intersectional Feminism and the Women's March

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Report

· mount holyoke · PRESIDENT’S REPORT · a note from the · PRESIDENT The College has always been a place where big visions take shape. For over 180 years, we have opened opportunities for students to deepen their understanding and sharpen their response to a fast-changing world with challenges both known and unknown. We prepare students to learn and to lead because in life and work, we know this is what makes all the difference. Now that we have been deeply engaged in the work for two years of our five-year Plan for 2021, I’m delighted to share our progress, including an overview of some of Mount Holyoke’s new strategic initia- tives. In January 2018, we opened the Dining Commons, a part of the new Community Center, which is now also nearing completion. With the extensive renovations to Blanchard Hall we are creating a co-curricular hub in support of student leadership and programs, as well as a coffee shop and pub. We’ve also added new residential, co-curricular, and academic spaces. These spaces are the heart of our community-building efforts, giving more attention to shared endeavors and creating a sense of belonging. They represent a commitment to place at Mount Holyoke, reminding us all of the power of relationships that is in the very warp and woof of the College and the Alumnae Association. There is an energy and excitement to our being in the same space at the same times each day to eat, talk, think, and debate in companionship and cooperation. I hope the stories in these pages excite you about our current initi atives and our plans for the future. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

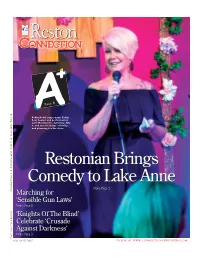

Restonreston

RestonReston Page 8 Robin Dodd (stage name Robin Rex) hosted and performed at Café Montmartre, Saturday, July 8, and was in charge of hiring and planning for the show. Classifieds, Page 10 Classifieds, ❖ RestonianRestonian BringsBrings Entertainment, Page 9 ❖ ComedyComedy toto LakeLake AnneAnne News,News, PagePage 33 Opinion, Page 4 MarchingMarching forfor ‘Sensible‘Sensible GunGun Laws’Laws’ News,News, PagePage 66 ‘Knights‘Knights OfOf TheThe Blind’Blind’ CelebrateCelebrate ‘Crusade‘Crusade AgainstAgainst Darkness’Darkness’ News,News, PagePage 33 Photo by Steve Broido www.ConnectionNewspapers.comJuly 19-25, 2017 online at www.connectionnewspapers.comReston Connection ❖ July 19-25, 2017 ❖ 1 South Lakes High School 2017 All Night Grad Party gratefully thanks our generous donors: Platinum ($500+) Emmert Family Harris Family FrozenYo Escape Room, Herndon Harvey Family Weber’s Pet Supermarket, Fox Mill Grealish Family Hawley Family Great Falls Area Ministries Hirshfeld Family Gold ($100 - 499) Hand & Stone Massage & Facial Spa Hughes Family Baser Family Harris Teeter, Spectrum Center Hunan East Restaurant Bond Family Harris Teeter, Woodland Crossing Irwin Family Chic Fil-A, Reston Jammula Family Jaeger Family Dlott Family Jersey Mike’s Subs, Reston Kanode Family Flippin’ Pizza, Reston Kalypso’s Sports Grill Karras Family Glory Days, Fox Mill & North Point Kong Family Kelly Family Golinsky Specific Chiropractic KSB Café of New York Konowe Family Greater Reston Arts Center King Pollo, Reston Kumar Family HoneyBaked Ham Lucia’s Italian Ristorante, -

Women's March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity

Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 0 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Originally posted on the blog of The American Prospect, January 6, 2017. Confederacy” By Laurie Green For those who believe Donald Trump’s election has further legitimized hatred and even violence, a “Women’s March on Washington” scheduled for January 21 offers an outlet to demonstrate mass solidarity across lines of race, religion, age, gender, national identity, and sexual orientation. May 06, 2020 More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (The Center for Jewish History via Flickr) The idea of such a march first ricocheted across social media just hours after the TV networks called the DIGITAL HISTORY election for Trump, when a grandmother in Hawaii suggested it to fellow Facebook friends on the private, pro-Hillary Clinton group page known as Pantsuit Nation. Millions of postings later, the D.C. march has mushroomed to include parallel events in 41 states and 21 cities outside the United States. An Más de 72: Digital Archive Review independent national organizing committee has stepped in to articulate a clear mission and take over https://notevenpast.org/womens-march-like-many-before-it-struggles-for-unity/[6/19/2020 8:58:41 AM] Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity - Not Even Past logistics. -

Commentary… Descent, Is Editor-At-Large at the J'accuse Coalition for Justice

בס״ד cannot acknowledge עש"ק פרשת בהר ISRAEL NEWS that history at the )בחקתי בא"י( 19 Iyar 5779 May 24, 2019 expense of Mizrahi Issue number 1245 A collection of the week’s news from Israel Jews, who with so many others, From the Bet El Twinning / Israel Action Committee of regardless of skin color, shared the Jerusalem 6:55 Beth Avraham Yoseph of Toronto Congregation desire for a Jewish state long before Toronto: 8:28 the establishment of Israel. The writer, an Israeli writer and activist of Iraqi and North African Commentary… descent, is editor-at-large at the J'accuse Coalition for Justice. No, Israel isn’t a Country of Privileged and Powerful White Europeans By Hen Mazzig Can Reform’s Embrace of Al Sharpton Be Justified? Along with resurgent identity politics in the United States and Europe, By Jonathan S. Tobin there is a growing inclination to frame the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in If the Rev. Al Sharpton were truly willing to repent for his past as a terms of race. According to this narrative, Israel was established as a refuge race-baiter and inciter of anti-Semitic violence, then having him speak at a for oppressed white European Jews who in turn became oppressors of Jewish event titled a “Consultation on Conscience” might be a good idea. people of color, the Palestinians. Perhaps that’s what the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism As an Israeli, and the son of an Iraqi Jewish mother and North African and its leader, Rabbi Jonah Pesner, thought they were doing when they Jewish father, it’s gut-wrenching to witness this shift. -

Across America, Millions Say: Black Lives Matter! NO to a Police State!

JUNE / JULY 2020, VOL. 47, NO. 5 peoplestribune.org Across America, millions say: Black Lives Matter! NO to a police state! Lansing, Michigan PHOTO: daymonjhartley.com Chicago BLM protest, June, 2020. Atlanta PHOTO: Sarah-Ji of loveandstrugglephotos.com PHOTO: John Ramspott DONATE OR SUBSCRIBE CONTENT About the People’s Tribune JUNE / JULY 2020 The People’s Tribune is devoted to the understanding that an economic system that doesn’t feed, clothe, house, or care 3 Black Lives Matter! NO to a police state! for its people must be and will be replaced with a system that meets the needs of the people. To that end, this paper is a tribune of the people. It is a voice of millions of everyday 4 Solidarity in the fight for Black Lives Matter people who are fighting to survive in an America in crisis. It helps build connections among these fighters and the Covid-19 kills people in prisons; awareness that together, we can create a whole new society 5 and world. Journalists denounce police violence Today, technology is permanently eliminating jobs. Our needs can only be met by building a cooperative society where we 6 All lives can’t matter until black lives matter the people, not the corporations, own the technology and the abundance it produces. Then, everyone’s needs will be provided for. Cancel the rent: Will we let more people 7 We welcome articles and artwork from those who are become homeless? engaged in the struggle to build a new society that is of, by and for the people. -

Viennaviennaand Oakton

ViennaViennaand Oakton KSR Pet Care Lead Trainer Page 8 Kathryn Anwyll practices walking on leash with Xena, the Poorman family’s German shepherd puppy as Robyn Poorman, of Vienna, her daughter Reagan Poorman, 5, and KSR Pet Care Owner Karen Rosenberg watch outside of the Tyson’s Corner Animal Hospital on Saturday, July 8. Classifieds, Page 10 Classifieds, ❖ Entertainment, Page 9 ❖ Opinion, Page 4 Paws-On Training in Tysons News, Page 3 Marching for ‘Sensible Gun Laws’ News, Page 6 Summer Book Clubs for Children A+, Page 8 Photo by Fallon Forbush/The Connection www.ConnectionNewspapers.comJuly 19-25, 2017 online atVienna/Oakton www.connectionnewspapers.com Connection ❖ July 19-25, 2017 ❖ 1 Sports Oakton Otters Win Two Meets in a Row Photos by Ed. Messina The Oakton Otters, bat- tling heavy rains and thun- der delays, dominated the boards in their last two dual meets, bringing their win- ning record to 2 and 1. In their second meet of the season (July 5), the Otter divers defeated Sleepy Hol- low with a final score of 49 to 21. Five Otter divers placed first in their respective categories: Finn MacStravic in Freshman Boys with a score of 59.6; Christina Angelicchio in Junior Girls with a score of 86.5; Jon An- thony Montel in Junior Boys with a score of 87.1; Katie Vaughan in Intermediate Girls with a score of 152.95; and Spencer Dearman in In- Josh Shipley termediate Boys with a score of 150.25. The Otters also swept the categories of Freshman Boys (Landon Nelson, second; and Zac Lee, third); Junior Girls (Kalina Montel, sec- ond); Junior Boys (Nico Shuster, second; and Max Messina, third); Intermedi- ate Girls (Claire Newberry, second; and Gillian MacStravic, third); and In- termediate Boys (Josh Shipley, second; and Blaise Wuest, third). -

The Rhetoric of Feminist Hashtags and Respectability Politics

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Spring 2018 Are We All #NastyWomen? The Rhetoric of Feminist Hashtags and Respectability Politics Kimberly Lynette Goode Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Goode, Kimberly L.. "Are We All #NastyWomen? The Rhetoric of Feminist Hashtags and Respectability Politics" (2018). Master of Arts (MA), Thesis, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/6bj5-7f60 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARE WE ALL #NASTYWOMEN? THE RHETORIC OF FEMINIST HASHTAGS AND RESPECTABILITY POLITICS by Kimberly Lynette Goode B.S. August 2015, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS ENGLISH OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2018 Approved by: Candace Epps-Robertson (Director) Julia Romberger (Member) Avi Santo (Member) ABSTRACT ARE WE ALL #NASTYWOMEN? THE RHETORIC OF FEMINIST HASHTAGS AND RESPECTABILITY POLITICS Kimberly Lynette Goode Old Dominion University, 2018 Director: Dr. Candace Epps-Robertson In a time where misogynistic phrases from political figures such as Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell are being reclaimed by feminists on Twitter, it is crucial for feminist rhetorical scholars to pay close attention to the rhetorical dynamics of such reclamation efforts. -

HATE CRIMES and the RISE of WHITE NATIONALISM Before the U.S

Written Testimony of Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) National President Morton A. Klein1 Hearing title: HATE CRIMES AND THE RISE OF WHITE NATIONALISM Before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary, 116th Congress Tuesday April 9, 2019, 10:00 a.m. Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2141 Chairman Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) Ranking Member Doug Collins (R-GA) Chairman Nadler, Ranking Member Collins, Members of the Committee: Thank you for holding this hearing. And thank you, Chairman Nadler, for stating in your November 27 letter that this Committee “will likely examine the causes of racial and religious violence.”2 For the past 25 years, I have served as president of the oldest pro-Israel organization in the country, the non-partisan Zionist Organization of America (the ZOA). A key ZOA mission is protecting American Jews and others from antisemitism and violence. As a child of Holocaust survivors, I’ve personally felt the horrors of unbridled antisemitism. I was born in a displaced persons camp in Germany, and grew up without the loving presence of most of my grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins, whom the Nazis murdered. The FBI reports that Jews are the victims in sixty percent (60%) of religiously-motivated hate crimes.3 Jew-hatred is the canary in the coal mine, the harbinger of hate in society at large. 1 ZOA Director of Special Projects Elizabeth Berney, Esq. assisted with this written testimony. 2 Congressman Jerry Nadler press release and letter, Nov. 27, 2018, at https://nadler.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=391395 -

Black Lives Matter Activists Denounced by Mothers of Victims for Exploiting Deaths of Tamir Rice and Others Killed by Police

افغانستان آزاد – آزاد افغانستان AA-AA چو کشور نباشـد تن من مبـــــــاد بدين بوم و بر زنده يک تن مــــباد ھمه سر به سر تن به کشتن دھيم از آن به که کشور به دشمن دھيم www.afgazad.com [email protected] زبانھای اروپائی European Languages Trévon Austin 22.03.2021 Black Lives Matter activists denounced by mothers of victims for exploiting deaths of Tamir Rice and others killed by police Samaria Rice, the mother of Tamir Rice, and Lisa Simpson, the mother of Richard Rishner, released a joint statement Tuesday accusing activists associated with the Black Lives Matter movement of profiting from the police killings of their children. December 15, 2014 photo of Samaria Rice [Credit: AP Photo/Mark Lennihan, File] Tamir Rice was just 12 years old when he was shot and killed by Cleveland, Ohio, police officers while playing in a park in 2014. Rishner, 18, was gunned down by Los Angeles police in 2016. Both killings and the decisions not to bring criminal charges against the [email protected] ١ www.afgazad.com officers involved have fueled mass protests against police violence in the US and internationally. “Tamika D. Mallory, Shaun King, Benjamin Crump, Lee Merritt, Patrisse Cullors, Melina Abdullah and the Black Lives Matter Global Network need to step down, stand back, and stop monopolizing and capitalizing off our fight for justice and human rights,” the statement said. “We never hired them to be the representatives in the fight for justice for our dead loved ones murdered by the police. The ‘activists’ have events in our cities and have not given us anything substantial for using our loved ones’ images and names on their flyers.” “We don’t want or need y’all parading in the streets accumulating donations, platforms, movie deals, etc. -

Resources for Anti-Racist Teaching (June 2020) Teaching Tolerance

Resources for Anti-Racist Teaching (June 2020) Teaching Tolerance website: https://www.tolerance.org/ Raising Race Conscious Children: http://www.raceconscious.org/2016/06/100-race-conscious- things-to-say-to-your-child-to-advance-racial-justice/ From the National Writing Project, if the desire for change leads you to seek new voices and new reading or listening recommendations for anti-racist and social justice teaching, check out "Resources for Peace and Justice”: https://writenow.nwp.org/resources-for-justice-and-peace- 17128aabdced Processing the Uprisings: Lunchtime Convos Sponsored by the Racial Justice Committee of the Caucus of Working Educatorshttps://www.facebook.com/shira.naomi.1/posts/10100222703527244 From Katie – two resources for talking with kids about race and racism: 1. From the National Museum of African American History and Culture: https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race 2. Embrace Race: https://www.embracerace.org/ The following comprehensive list was shared with Kathleen: 1. The Paradox of Black Lives Matter (by Prof. Myrna Santiago at SMC) a. Letter to My Son (by Ta Nehisi Coates), cited in Prof Santiago's piece. 2. Ep. 2: Say Her Name — Breonna Taylor, a Conversation with Tamika Mallory and Taylor Family Attorney Lonita Baker 3. Re/Watch Dr. Kimberle Crenshaw's INTERSECTIONALITY TedTalk 4. Letters for Black Lives (“Letters for Black Lives is a set of crowdsourced, multilingual, and culturally-aware resources aimed at creating a space for open and honest conversations about racial justice, police violence, and anti-Blackness in our families and communities”) 5. A Letter From Young Asian-Americans To Their Families About Black Lives Matter 6. -

Response Daily: Assembly 2018

Assembly Edition | may 20, 2018 issue 3 Civil Rights Champions Urge United resMethodist Womenpo to Endnse Cradle to Prison Pipeline and Mass Incarceration by YVETTE MOORE Two champions of the movement to end U S branded felons, a label that subject them to legal mass incarceration and the cradle to prison discrimination and loss of the right to vote pipeline caused by poverty addressed United Alexander said the economy in many inner cities Methodist Women members in a morning ple- collapsed in the early 1980s as companies moved Today’s scriptures nary with a racial justice theme at The Power of overseas seeking “new plantations” of cheap labor, Luke 1:28b Bold Assembly in Columbus, Ohio, May 19 and this fueled the rise of illicit drug abuse, its com- Revelation 19:6-7a Michelle Alexander, author of The New im merce and the war on drugs The war on drugs Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color- also happened in the context of a massive back- blindness, and Marian Wright Edelman, founder lash against the civil rights movement, she said Alexander realized the spiritual core of the prob- Social Media lem of mass incarceration while speaking about at Assembly her book at Iliff Theological School at the invi- Join us on social media using tation of Vincent Harding, a racial justice advo- hashtag #UMWAssembly2018 cate and speech writer for the Rev Martin Luther Be sure to tag us @UMWomen King Jr “I cited the data and statistics and how Supreme Court had closed doors, and I went on, and at the United Methodist end of speech, he said, ‘Sister,