Narrativizing Middle School Students' Intersectional Perceptions of Whiteness in Literacy Instruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Movies and Television Programs Featuring Psychotherapy and People with Mental Disorders Timothy C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenKnowledge@NAU Recommended Movies and Television Programs Featuring Psychotherapy and People with Mental Disorders Timothy C. Thomason Abstract This paper provides a list of 200 feature films and five television programs that may be of special interest to counselors, psychologists and other mental health professionals. Many feature characters who portray psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, or psychotherapists. Many of them also feature characters who have, or may have, mental disorders. In addition to their entertainment value, these videos can be seen as fictional case studies, and counselors can practice diagnosing the disorders of the characters and consider whether the treatments provided are appropriate. It can be both educational and entertaining for counselors, psychologists, and others to view films that portray psychotherapists and people with mental disorders. It should be noted that movies rarely depict either therapists or people with mental disorders in an accurate manner (Ramchandani, 2012). Most movies are made for entertainment value rather than educational value. For example, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a wonderfully entertaining Academy Award-winning film, but it contains a highly inaccurate portrayal of electroconvulsive therapy. It can be difficult or impossible for a viewer to ascertain the disorder of characters in movies, since they are not usually realistic portrayals of people with mental disorders. Likewise, depictions of mental health professionals in the movies are usually very exaggerated or distorted, and often include behaviors that would be considered violations of professional ethical standards. Even so, psychology students and psychotherapists may find some of these movies interesting as examples of what not to do. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

Nov. 12, 2020 $1 Black Vote Dumps Trump by Monica Moorehead and Louisville, Ky., Respectively This Past Spring

¡La autodefensa es un derecho! 12 Editorial Niños perdidos 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 62, No. 46 Nov. 12, 2020 $1 Black vote dumps Trump By Monica Moorehead and Louisville, Ky., respectively this past spring. There were also signs saying that Once it was confirmed on Nov. 7 that the election was not about Biden/Harris, the Joe Biden and Kamala Harris ticket but about the defeat of Trump and that had defeated Trump, literally tens of the struggle will continue. thousands of people around the U.S. There was also the recognition of his- spontaneously took to the streets for tory being made with Kamala Harris hours in jubilation and celebration. Not being the first woman and the first only were downtown areas taken over woman of color to become a vice-presi- but also neighborhoods, block by block, dent elect. While describing herself as a where traffic came to a standstill with Black woman of Jamaican heritage, her horns blaring. family roots also come from the Indian While the majority of those in the state of Tamil Nadu. There were thou- streets were young people, all ages partic- sands of women, including Muslims, car- ipated regardless of nationality, gender, rying signs expressing equal if not more gender expression and abilities. People support for Harris winning than Biden. Lead banners of march in Philadelphia Center City, Nov. 7. WW PHOTO: JOE PIETTE could hardly wait to let off steam after While there was a wide gauntlet of waiting for what must have seemed like political views of people who poured out an eternity— if only five days— to see if in the streets of Philadelphia, Atlanta, the four-year nightmare of Trump would New York City, Chicago, the Bay Area, Philly celebrates, come to an end. -

President's Report

· mount holyoke · PRESIDENT’S REPORT · a note from the · PRESIDENT The College has always been a place where big visions take shape. For over 180 years, we have opened opportunities for students to deepen their understanding and sharpen their response to a fast-changing world with challenges both known and unknown. We prepare students to learn and to lead because in life and work, we know this is what makes all the difference. Now that we have been deeply engaged in the work for two years of our five-year Plan for 2021, I’m delighted to share our progress, including an overview of some of Mount Holyoke’s new strategic initia- tives. In January 2018, we opened the Dining Commons, a part of the new Community Center, which is now also nearing completion. With the extensive renovations to Blanchard Hall we are creating a co-curricular hub in support of student leadership and programs, as well as a coffee shop and pub. We’ve also added new residential, co-curricular, and academic spaces. These spaces are the heart of our community-building efforts, giving more attention to shared endeavors and creating a sense of belonging. They represent a commitment to place at Mount Holyoke, reminding us all of the power of relationships that is in the very warp and woof of the College and the Alumnae Association. There is an energy and excitement to our being in the same space at the same times each day to eat, talk, think, and debate in companionship and cooperation. I hope the stories in these pages excite you about our current initi atives and our plans for the future. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Collection of Television Press Kits, 1958, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c87082fc No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of television press kits, 1958, ca. 1974-ca. 2004 Finding aid prepared by Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 1908 1 television press kits, 1958, ca. 1974-ca. 2004 Title: Collection of television press kits Collection number: 1908 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 9.5 linear ft.(19 boxes and 1 flat box.) Date (inclusive): 1958, ca. 1974-2004 Abstract: This collections documents a variety of television show genres broadcast on networks such as ABC, CBS, NBC, HBO, PBS, SHOWTIME, and TNT. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the caollection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

HOW the MANHATTAN DISTRICT ATTORNEY HOARDS MONEY, PERPETUATES ABUSE of SURVIVORS, and GAGS THEIR ADVOCATES Table of Contents

HOW THE MANHATTAN DISTRICT ATTORNEY HOARDS MONEY, PERPETUATES ABUSE of SURVIVORS, and GAGS THEIR ADVOCATES Table of Contents INTRODUCTION S&P NY PERSPECTIVES ON PROSECUTING OFFICES • Prosecutors Are Our Opponents, Not Our Allies • We Will Not Prosecute Our Way Out of Violence PROSECUTING OFFICES HOARD PUBLIC FUNDS AND SABOTAGE SURVIVOR SAFETY • How Prosecutors Accumulate Funds • Where Does This Money Go? • DA Funding Undermines Survivors’ Collective Safety: The Role of Mainstream Gender-based Violence Organizations • Prosecutor Allies: How Did the Anti-violence Movement Lose Its Way? • Relying on Criminalization and Prosection: Protecting White Women, Leaving other Survivors Behind • An Abuse of Discretion: How Prosecutors Criminalize Survivors Acknowledgements WHAT WE COULD EXPECT FROM THE CANDIDATES • Where Do the Candidates Stand on Funding? Deep appreciation for all of our comrades inside NY prisons and jails that • Criminalized Survivor Case Study: shape what we know about criminalization and prosecutors’ everyday Snapshot of the Tracy McCarter’s Story violence. We will continue to fight for your freedom and healing. Love and • Fool’s Gold: gratitude to Tracy McCarter and the #StandWithTracy defense team for District Attorney Candidates and Sex Crime Unit Reform allowing us to share her story. Thanks to Jett George for their beautiful (and swiftly produced!) illustrations and design. Forever gratitude to the abolitionist, Black feminist queer disabled organizers, and survivors before ACTION STEPS TO GET INVOLVED us that promised us that there is another way to bring healing and safety to our communities, without state violence. Introduction The Anti-Prosecution Working Group of Survived & Punished NY exists to Beyond the election, we hope this zine inspires New Yorkers to start or build power and energy toward a future free of all prosecutorial join campaigns to #DefundDAs and imagine safety, healing, and justice for mechanisms in New York. -

Concerned, Meet Terrified Intersectional Feminism and the Women's March

Women's Studies International Forum 69 (2018) 49–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif Concerned, meet terrified: Intersectional feminism and the Women's March T ⁎ Sierra Brewer, Lauren Dundes Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The first US Women's March on January 21, 2017 seemingly had the potential to unite women across race. To Women's March assess the progress of feminism towards an increasingly intersectional feminist approach, the authors collected Trump and analyzed interview data from 20 young African American women who shared their impressions of the Clinton Women's March that followed Donald Trump's inauguration during the month after the march. Interviewees White feminism believed that Trump's election and his sexism spurred the march, prompting the participation of many women Intersectional feminism who had not previously embraced feminism. Interviewees suggested that the march provided white women with Pussy hat ff Race a means to protest the election rather than a way to address social injustice disproportionately a ecting lower Gender social classes and people of color. Interviewees believed that a racially inclusive feminist movement would Intersectionality remain elusive without a greater commitment to intersectional feminism. African American Introduction shaming of Latina Alicia Machado, crowned Miss Universe in 1996) (Chozick & Grynbaum, 2017). Indeed, the 2005 hot mic comment ap- “If I see that white folks are concerned, then people of color need to peared to be a principal focal point of the march for white women be terrified.” galvanized by Trump bragging that fame allowed him to be sexually In the above quotation, Women's March co-chair Tamika Mallory aggressive with women without their consent. -

Nondiscrimination in Health and Health

Officers May 20, 2020 Chair Judith L. Lichtman National Partnership for Women & Families Vice Chairs Thomas A. Saenz Mexican American Legal The Honorable Alex Azar Derek Kan Defense and Educational Fund Hilary Shelton Secretary Executive Associate Director NAACP Secretary/Treasurer U.S. Department of Health and Office of Management and Budget Lee A. Saunders American Federation of State, Human Services 725 17th Street NW County & Municipal Employees 200 Independence Avenue SW Washington, DC 20503 Board of Directors Kevin Allis National Congress of American Indians Washington, DC 20201 Kimberly Churches AAUW Paul Ray Kristen Clarke Lawyers' Committee for Roger Severino OIRA Administrator Civil Rights Under Law Alphonso B. David Director Office of Management and Budget Human Rights Campaign Rory Gamble Office for Civil Rights 725 17th Street NW International Union, UAW Lily Eskelsen García U.S. Department of Health and Washington, DC 20503 National Education Association Fatima Goss Graves Human Services National Women's Law Center Mary Kay Henry 200 Independence Avenue SW Seema Verma Service Employees International Union Sherrilyn Ifill Washington, DC 20201 Administrator NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services David H. Inoue Japanese American Citizens League 7500 Security Boulevard Derrick Johnson NAACP Baltimore, Maryland 21244 Virginia Kase League of Women Voters of the United States Michael B. Keegan People for the American Way Samer E. Khalaf Re: Nondiscrimination in Health and Health -

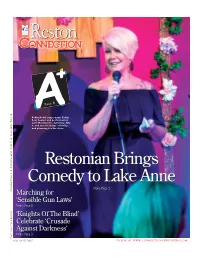

Restonreston

RestonReston Page 8 Robin Dodd (stage name Robin Rex) hosted and performed at Café Montmartre, Saturday, July 8, and was in charge of hiring and planning for the show. Classifieds, Page 10 Classifieds, ❖ RestonianRestonian BringsBrings Entertainment, Page 9 ❖ ComedyComedy toto LakeLake AnneAnne News,News, PagePage 33 Opinion, Page 4 MarchingMarching forfor ‘Sensible‘Sensible GunGun Laws’Laws’ News,News, PagePage 66 ‘Knights‘Knights OfOf TheThe Blind’Blind’ CelebrateCelebrate ‘Crusade‘Crusade AgainstAgainst Darkness’Darkness’ News,News, PagePage 33 Photo by Steve Broido www.ConnectionNewspapers.comJuly 19-25, 2017 online at www.connectionnewspapers.comReston Connection ❖ July 19-25, 2017 ❖ 1 South Lakes High School 2017 All Night Grad Party gratefully thanks our generous donors: Platinum ($500+) Emmert Family Harris Family FrozenYo Escape Room, Herndon Harvey Family Weber’s Pet Supermarket, Fox Mill Grealish Family Hawley Family Great Falls Area Ministries Hirshfeld Family Gold ($100 - 499) Hand & Stone Massage & Facial Spa Hughes Family Baser Family Harris Teeter, Spectrum Center Hunan East Restaurant Bond Family Harris Teeter, Woodland Crossing Irwin Family Chic Fil-A, Reston Jammula Family Jaeger Family Dlott Family Jersey Mike’s Subs, Reston Kanode Family Flippin’ Pizza, Reston Kalypso’s Sports Grill Karras Family Glory Days, Fox Mill & North Point Kong Family Kelly Family Golinsky Specific Chiropractic KSB Café of New York Konowe Family Greater Reston Arts Center King Pollo, Reston Kumar Family HoneyBaked Ham Lucia’s Italian Ristorante, -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair,