Phyllis Lamphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seattle City Map 1 Preview

sseattle-cm-set1.indd 1 Q e A B CDE F G H J K L M N O P a t N N t N N l E e N e Legend N 0500mN S E - N e t c N# 00.25miles N 43rd St University of e e e v m Av N 43rd St N 43rd St y NE v U DISTRICT E l N Seattle Ave M NE e ve A NE NE 43rd St Washington E NE d N - t t Av n Av NE Top Sight Short List i s A N e n s d N o n e dN y l Wa e n 5 ay VU ve NE W e N e s o o va o i e vd NE R t o t L v N Motor Pl Park Ave N a 1 Routes t c ve Nve w n e s y l e . NE 42nd St m y h Av h n e lyn Ave Ave lyn N n B n n i a l i E n l Stone Way Tollway a e a r e i a A a 8thAve 7t r d 9th A y r W elt e N e D v ke Bl ord Ave k r v d F F ide Ave Freeway l r Ph W Winslow P Salmon E 99 N 42nd St N 42nd St e äb e Av 15th O Memoria s 1 P NE11th Ave 1 G A Quad 12th Ave N a r d y stern Ave N sev Primary Rd Bay N Brook n 1 y NE 42nd St Burke Ave a e A N 42nd St N P Corliss A NW 42nd N NW 42nd St n St Ea v nn Secondary Rd e W e Woodland AshworthA ve Montla Woodlawn Ave N Roo d NE Tertiary Rd Wallingf Su N NE A Henry Art a e W s NE 41st St Gallery Lane a ra ra N 41st St N 41st University of Washington 513 o St P `ß Path NW 41st St AveNE r A N 41st St AVisitor Center Pedestrian St/Steps 4th Ave NE 1st Ave NE Au W nsmore Ave N 5th 5th 2nd Ave N A e N Central Plaza N 41st St NE Campus Pkwy e D Latona Av e NE 4 A Transport AveN 0th St (Red Square) Suzzall o NW 40th St v Av cific St n n a A P Airport N 40th St N Library n NE 40th St d e Bus r NE 40th St Rainier St e') A NW 40th d N 40th St tma 3 N -

02 Pike Place Market

The Market as Organizer of an Urban CommunitY Pike Place Market, Seattle The Pike Place Market, which climbs a steep hillside not far.above the Seattle waterfront (fig. 2-1), is one of America's great urban places. Some people, hearing its name without ever having been there, might think the Pike Place Market won the Rudy Bruner Award for Excellence in the Urban Environment because it is a "festival marketplace." They would be wrong, and it is worth pointing out why. The places that developers call festival markets are shopping centers that offer food and goods in an entertaining urban setting. Festival markets have wonderful aromas, public performers, and lots of small shops. They typically have interesting views. And all these things can be found at Pike Place, which is certainly festive. But the differences between Pike Place and a festival market are profound. Unlike festival markets, the Pike Place Market is a place where people live as well as shop. Some of Pike Place's inhabitants are wealthy, but a gleater number are poor or of moderate income; they occupy new or rehabilitated apartments mainly because an effort was made to obtain government subsidies. The chain merchants that operate in festival mar- kets are not allowed at Pike Place; on the contrary, Pike Place strives to rely on independent enterprises whose owners are on the premises, making their concerns and their personalities felt. Although there are plenty of restaurants and take-out food stands at Pike Place, just as in a festival market, much of the food at Pike Place comes in a basic, less expensive form-raw, forhome consumption. -

Spectator 1959-12-04 Editors of the Ps Ectator

Seattle nivU ersity ScholarWorks @ SeattleU The peS ctator 12-4-1959 Spectator 1959-12-04 Editors of The pS ectator Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/spectator Recommended Citation Editors of The peS ctator, "Spectator 1959-12-04" (1959). The Spectator. 658. http://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/spectator/658 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The peS ctator by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. See Sports AGGIES DUMP CHIEFS, 85-73 ... Page 8 Unrestricted Accreditation Granted S.U. for 5 Years S.U. was granted a five-year unre- self-improvement which it stimulates. stricted accreditation by the Northwest They're encouraging an institution to be Association for the Accreditation of Sec- as strong as possible. Then they do as ondary and Higher Schools, it was an- much as they can to help that institu- nounced late yesterday by Fr. John E. tion." Gurr,S.J.,academic vice-president. THE ASSOCIATION met at the Dav- enport Hotel in Spokane from Nov. 29 to "WE HAVE BEEN members of this Dec. 3. During the meeting of the higher Association and fully accredited since commission, (theone which accredits col- 1937," stated Fr. Gurr. "In 1952, the leges and universities), the report on group decided that all member institu- S.U.s accreditation visit was reviewed tions would be visited and re-accredited and the recommendation voted upon. by 1960. This was the reason for S.U.s The Very Rev. A. A. Lemieux, S.J., visit last month." president of S.U., was present at the Mon- "In some cases," Father added, "the day night session. -

Spectator 1958-04-03 Editors of the Ps Ectator

Seattle nivU ersity ScholarWorks @ SeattleU The peS ctator 4-3-1958 Spectator 1958-04-03 Editors of The pS ectator Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/spectator Recommended Citation Editors of The peS ctator, "Spectator 1958-04-03" (1958). The Spectator. 611. http://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/spectator/611 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The peS ctator by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. Survey Shows SU's Standards Superior to PCC Ina recent series of articles originating in the Portland sion are lower than those of Pa- petition should be accompanied by to theuniversity for admission; 149 Oregonian,irresponsible chargesregarding cific Coast Conference member evidence that the student is able were refused admission; 11 per the academic stand- making Seat- than cent on probation; 89 policies schools, it easier for to do better work is indicated were taken ards and at Seattle University have been publicized tle University to attract athletes by his high school records." per cent were accepted as regular and headlined. with poor academic records." Seattle University's insistence students. Among those admitted Because these allegations tend to discredit Seattle Uni- The Facts: The standard re- upon a 2.00 gradepoint average on probation, there were six stu- versity's reputation quirement for admission to Seattle would then indicate thatits admis- dent athletes who indicated inten- academic and to cast unfavorable reflec- participate in or students, University is graduation from an sion standards are equal to"School tion to one more tion upon its university officials present the follow- accredited high school with a 2.00 C" and higher than "School A" of the four sportsat the university. -

SCULPTURE Title: North Totem Pole, 1984 Artist

SCULPTURE Title: North Totem Pole, 1984 Artist: James Bender Location: Victor Steinbrueck Park, corner of Western & Virginia Description: Western red cedar carved in Haida-inspired style. M. Oliver initial design. J. Bender final design and carver. Metaphorical figures of the Raven, Human, Little Human, Orca, Little Raven and Bear holding a hawk. Commissioned 1983 by architect Victor Steinbrueck. www.nwart- jpbender.com. Title: Farmer’s Pole, 1984 Artist: James Bender Location: Victor Steinbrueck Park, corner of Western & Virginia Description: Western red cedar tribute pole carved to celebrate the Market farmers. Man and a woman wear “Honored Farmer – 1984” badges . Commissioned 1983 by architect Victor Steinbrueck. Concept and design was a collaboration between Bender and Steinbrueck. www.nwart- jpbender.com. Title: Sasquatch, circa 1970’s Artist: Richard W. Beyer (1925-2012) Location: North Wall, Economy Building Atrium Description: Seven foot Sasquatch wood carving. Mythical forest creature brought well-being to local tribes. Reflects dependence on generosity and terrifying power of thick forests. Artist sold smaller versions from a market stall he had during his early career. Between 1968 and 2006, he created over 90 different sculptures for public spaces in cities throughout the country that reflect local values and lore. www.richbeyersculpture.com Title: Rachel the Piggy Bank, 1986 Artist: Georgia Gerber Location: Corner of Pike Street and Pike Place Description: Bronze mascot of Pike Place Market Foundation. Model was an old sow living near the artist’s Whidbey Island home. Each year she collects thousands of coins and bills in multiple currencies which supports the Market’s food bank, child care center, medical clinic and senior center. -

Victor Steinbrueck Papers, 1931-1986

Victor Steinbrueck papers, 1931-1986 Overview of the Collection Creator Steinbrueck, Victor Title Victor Steinbrueck papers Dates 1931-1986 (inclusive) 1931 1986 Quantity 20.32 cubic feet (23 boxes and 1 package) Collection Number Summary Papers of a professor of architecture, University of Washington. Repository University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Special Collections University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, WA 98195-2900 Telephone: 206-543-1929 Fax: 206-543-1931 [email protected] Access Restrictions Open to all users, but access to portions of the papers restricted. Contact Special Collection for more information Languages English Sponsor Funding for encoding this finding aid was partially provided through a grant awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Biographical Note Victor Steinbrueck was born in 1911 in Mandan, North Dakota and moved with his family to Washington in 1914. Steinbrueck attended the University of Washington, earning a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1935. He joined the faculty at the University of Washington in 1946 and taught until his retirement in 1976. He was the author of Seattle Cityscape (1962), Seattle Cityscape II (1973) and a collections of his drawings, Market Sketchbook (1968). Victor Steinbrueck was Seattle's best known advocate of historic preservation. He led the battle against the city's redevelopment plans for the Pike Place Market in the 1960s. In 1959, the City of Seattle, together with the Central Association of Seattle, formulated plans to obtain a Housing and Urban Development (HUD) urban renewal grant to tear down the Market and everything else between First and Western, from Union to Lenora, in order to build a high rise residential, commercial and hotel complex. -

Oral History Interview with George Tsutakawa, 1983 September 8-19

Oral history interview with George Tsutakawa, 1983 September 8-19 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with George Tsutakawa on September 8, 12, 14 & 19, 1983. The interview took place in Seattle, WA, and was conducted by Martha Kingsbury for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview DATE: SEPTEMBER 8, 1983 [Tape 1; Side A] [GEORGE TSUTAKAWA reviewed the transcript and added clarification, particularly about the World War II years. His added comments with his initials are in brackets--Ed.] MARTHA KINGSBURY: George, why don't we start by talking about a lot of biographical matters. I'd like to know about your personal background, your family, your growing up in Seattle and Japan also, education. GEORGE TSUTAKAWA: Uh huh. Well, let's see now. My father was a merchant who came to Seattle in 1905, and he started a small business and eventually he gets involved in fairly large company exporting and importing American goods and Japanese goods. He, as I recall, had business in Japanese food, clothing, art goods, and all sorts of things from Japan, and then in turn he was sending lumber from the Northwest to Japan. He also dealt in scrap metal and just anything. MARTHA KINGSBURY: That he sent to Japan? GEORGE TSUTAKAWA: Yeah, he sent to Japan. -

Richard a C Greene

Seattle Post-Intelligencer 2nd SECTION Radio-TV Women Today s Fri •• Oct. II. 1968 ~.S It is another canard, says Gallant, that Greene did not discuss the issues: it is charged that, in Emmetl Watson beating his opponents, Bob Odman, Stanley Gallup, IInl1llllmlllllllllllllUlIlIllInnnnlllllllUmlillfiillllmllUlilUllllnlllllllllUIIIIIIIIJIIWIIJlllIIlIU!lORIIIIIIIIIUllill. and Bob Satiacum in the primaries, he did not make a single speech. "Not true," s·ays Gallant. "He spoke to me twice during the campaign." Out of these talks emerged the substance of Green.e, the This, Our City candidate for land commissioner. "I will go out and bravely commission the land," he said. He also plans to increase. the state's natural resources by mmmJnl1l1llllnnl!lllllllllmnnnllnllnnnnnmnmlll1ll1111l1ll1llll1ll1ll11111ll1111lll1llnnnlD1llnllDlJm\IIIID declaring Boeing a Wilderness Area. As land com missioner, he would actively work for the amalga Man for Our Times mation of the towns of Forks and Pysht into Pysht Forks. He developed a plan to give Eastern Wash OCCASIONALLY, a candidate comes alon.g ington to Idaho. who, by the force of his personality, his ideals and A SECOND TALK preceded candidate Greene's integrity, becomes a political force, in and of him departure for the University of Hawaii, where he self. JFK was such a candidate. Wendell Wilkie was now teaches Greek and Latin. At this time, he re another, and so were Adlai Stevenson, Teddy Roo fined his plan to turn Boeing into a Wilderness Area by proposing its transfer to the Olympic Rain For· sevelt and Fiorello LaGuardia. Today they call it est, "where the heavy rains will keep pickets from "charisma," the quality that not only attracts fol picketing for higher wages, thus benefiting the lowers, but sets a tone, a style, a force-in-being; the stockholders." He also formulated his proposal to "it" quality, the drive to inspire greatness in others. -

P I K E P L a C E M a R K

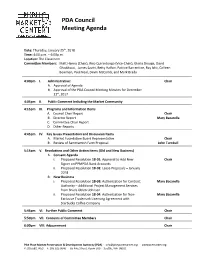

PDA Council Meeting Agenda Date: Thursday, January 25th, 2018 Time: 4:00 p.m. – 6:00p.m. Location: The Classroom Committee Members: Matt Hanna (Chair), Rico Quirindongo (Vice-Chair), Gloria Skouge, David Ghoddousi, James Savitt, Betty Halfon, Patrice Barrentine, Ray Ishii, Colleen Bowman, Paul Neal, Devin McComb, and Mark Brady 4:00pm I. Administrative: Chair A. Approval of Agenda B. Approval of the PDA Council Meeting Minutes for December 21st, 2017 4:05pm II. Public Comment Including the Market Community 4:15pm III. Programs and Information Items A. Council Chair Report Chair B. Director Report Mary Bacarella C. Committee Chair Report D. Other Reports 4:45pm IV. Key Issues Presentation and Discussion Items A. Market Foundation Board Representative Chair B. Review of Sammamish Farm Proposal John Turnbull 5:15pm V. Resolutions and Other Action Items (Old and New Business) A. Consent Agenda i. Proposed Resolution 18-01: Approval to Add New Chair Signer on PPMPDA Bank Accounts ii. Proposed Resolution 18-02: Lease Proposals – January 2018 B. New Business i. Proposed Resolution 18-03: Authorization for Contract Mary Bacarella Authority – Additional Project Management Services from Shiels Obletz Johnsen ii. Proposed Resolution 18-04: Authorization for Non- Mary Bacarella Exclusive Trademark Licensing Agreement with Starbucks Coffee Company 5:45pm VI. Further Public Comment Chair 5:50pm VII. Concerns of Committee Members Chair 6:00pm VIII. Adjournment Chair Pike Place Market Preservation & Development Authority (PDA) · [email protected] · pikeplacemarket.org P: 206.682.7453 · F: 206.625.0646 · 85 Pike Street, Room 500 · Seattle, WA 98101 PDA Council Meeting Minutes Thursday, December 21, 2017 4:00 p.m. -

Comprehensive List of Seattle Parks Bonus Feature for Discovering Seattle Parks: a Local’S Guide by Linnea Westerlind

COMPREHENSIVE LIST OF SEATTLE PARKS BONUS FEATURE FOR DISCOVERING SEATTLE PARKS: A LOCAL’S GUIDE BY LINNEA WESTERLIND Over the course of writing Discovering Seattle Parks, I visited every park in Seattle. While my guidebook describes the best 100 or so parks in the city (in bold below), this bonus feature lists all the parks in the city that are publicly owned, accessible, and worth a visit. Each park listing includes its address and top features. I skipped parks that are inaccessible (some of the city’s greenspaces have no paths or access points) and ones that are simply not worth a visit (just a square of grass in a median). This compilation also includes the best of the 149 waterfront street ends managed by the Seattle Department of Transportation that have been developed into mini parks. I did not include the more than 80 community P-Patches that are managed by the Department of Neighbor- hoods, although many are worth a visit to check out interesting garden art and peek at (but don’t touch) the garden beds bursting with veggies, herbs, and flowers. For more details, links to maps, and photos of all these parks, visit www.yearofseattleparks.com. Have fun exploring! DOWNTOWN SEATTLE & THE Kobe Terrace. 650 S. Main St. Paths, Seattle Center. 305 Harrison St. INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT city views, benches. Lawns, water feature, cultural institutions. Bell Street Park. Bell St. and 1st Ave. Lake Union Park. 860 Terry Ave. N. to Bell St. and 5th Ave. Pedestrian Waterfront, spray park, water views, Tilikum Place. 2701 5th Ave. -

Westside Seattle 4-7-17

WEST SEATTLE | P. 3 BALLARD | P. 5 AMANDA KNOX | P. 7 Whole Foods Amazon Fresh Mask- won’t open. opens in Ballard. making. FRIDAY, APRIL 7, 2017 | Vol. 99, No. 14 Westside Seattle Your neighborhood weekly serving Ballard, Burien/Highline, SeaTac, Des Moines, West Seattle and White Center INSIDE » P. 4 Port Noise Complaint See our listings on page 18 4700 42nd S.W. • 206-932-4500 • BHHSNWRealEstate.com © 2017 HSF Aliates LLC. 2 FRIDAY, APRIL 7, 2017 WESTSIDE SEATTLE FRIDAY, APRIL 7, 2017 | Vol. 99, No. 14 A note about some changes Newspapers included The Federal Way News, Des you travel, and someone asks you where you are Moines News, West Seattle Herald and eventually from, you probably do not say “Boulevard Park” or The Highline Times and Ballard News Tribune. Alki”. Thus, Westside Seattle, our new name. Each community has a distinct character. And still does. But in the years since, the communities have What is different grown together in a way. We are less likely to chase sirens than in the In the last few years, we began to recognize that past and now leave that to the blogs. Instead, Ballard News-Tribune, Highline Times, news did not stop at our circulation boundaries, we offer good writing, opinion, journalism, and West Seattle Herald that people moved around in the region as families more in-depth coverage along with feature sto- grew. The children of parents in Burien might settle ries about people whose lives merit recognition. Jerry Robinson Publisher Emeritus — in Ballard or West Seattle. Everything began to be This coverage will never end because our re- 1951 - 2014 connected. -

Pike Place Market and America's First Preservation & Development Authority

Fig 1: Pike Place Market Historic District (H. Tieben 2011) Heritage Preservation as a Process: Pike Place Market and America’s first Preservation & Development Authority Hendrik Tieben School of Architecture, The Chinese University of Hong Kong In 2006, Hong Kong experienced a heated heritage debate related to the demolition of Lee Tung Street, Star Ferry and Queens Pier. Two years later, with the Urban Renewal Strategy Review and the initiative ―Conserving Central‖ HKSAR Government made important steps to respond to the growing community concerns. Since then the focus of the debate shifted to the questions: how to balance preservation and development; and how to conserve buildings not just as physical shells but in connection with the surrounding community life. The following paper presents the case of the Seattle‘s Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority (PDA) which, although dating back to the 1960-70s, provides an example that might inspire the current debate in Hong Kong. Created in 1973, the Pike Place Market PDA was the first such authority in the USA. Since then, it was able to keep the market district as a vibrant centre of Seattle‘s Downtown and make it one of the most important tourist destinations in the Washington State. The PDA was created as a result of a citizen protest against an urban renewal project which had been proposed by members of the downtown business community and backed by the City Government and would have destroyed the entire market area. As it even extends its influence to the more renowned examples of the preservation movement in New York, the case has been regarded as the precursor of new environmental politics (Sanders, 2010).