Pike Place Market and America's First Preservation & Development Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seattle City Map 1 Preview

sseattle-cm-set1.indd 1 Q e A B CDE F G H J K L M N O P a t N N t N N l E e N e Legend N 0500mN S E - N e t c N# 00.25miles N 43rd St University of e e e v m Av N 43rd St N 43rd St y NE v U DISTRICT E l N Seattle Ave M NE e ve A NE NE 43rd St Washington E NE d N - t t Av n Av NE Top Sight Short List i s A N e n s d N o n e dN y l Wa e n 5 ay VU ve NE W e N e s o o va o i e vd NE R t o t L v N Motor Pl Park Ave N a 1 Routes t c ve Nve w n e s y l e . NE 42nd St m y h Av h n e lyn Ave Ave lyn N n B n n i a l i E n l Stone Way Tollway a e a r e i a A a 8thAve 7t r d 9th A y r W elt e N e D v ke Bl ord Ave k r v d F F ide Ave Freeway l r Ph W Winslow P Salmon E 99 N 42nd St N 42nd St e äb e Av 15th O Memoria s 1 P NE11th Ave 1 G A Quad 12th Ave N a r d y stern Ave N sev Primary Rd Bay N Brook n 1 y NE 42nd St Burke Ave a e A N 42nd St N P Corliss A NW 42nd N NW 42nd St n St Ea v nn Secondary Rd e W e Woodland AshworthA ve Montla Woodlawn Ave N Roo d NE Tertiary Rd Wallingf Su N NE A Henry Art a e W s NE 41st St Gallery Lane a ra ra N 41st St N 41st University of Washington 513 o St P `ß Path NW 41st St AveNE r A N 41st St AVisitor Center Pedestrian St/Steps 4th Ave NE 1st Ave NE Au W nsmore Ave N 5th 5th 2nd Ave N A e N Central Plaza N 41st St NE Campus Pkwy e D Latona Av e NE 4 A Transport AveN 0th St (Red Square) Suzzall o NW 40th St v Av cific St n n a A P Airport N 40th St N Library n NE 40th St d e Bus r NE 40th St Rainier St e') A NW 40th d N 40th St tma 3 N -

Tourist Guide to Seattle – Fall, 2019

Tourist Guide to Seattle – Fall, 2019 Planned group outings for Saturday: Sky View Observatory with (Dutch treat) Lunch option: Walk three blocks up Cherry Street (uphill) to the Columbia Center, the tallest skyscraper in Seattle (and Washington State) at 933 feet. You’ll take an elevator to the 73rd floor for a panoramic view of the Emerald City. $XX, paid in advance on your registration form. You have the option of a casual lunch there. Sign up only if you do not have a meeting scheduled from 12 noon to 1:30 Saturday. Beneath the Streets Tour: Take a 75-minute historical tour of Seattle’s 1890s architecture and the underground passageways that were left behind as Seattle built on top of the downtown that burned in the Great Fire of 1889. $15, paid in advance on your registration form. Tour involves 6 flights of stairs over one hour. Sign up only if you have no meeting Saturday from 2:15-3:30 pm. A second tour MAY be available for those in town Sunday, 2:00-3:15, paid in advance (refunds if it doesn’t go). On your own ----- Near the Courtyard Marriott: OUTINGS FOR 45 MINUTES-1 HOUR: Smith Tower – view and history: Walk out of the Hotel and turn left. At the end of the block is the Smith Tower, built in 1914. Take the original Otis elevator (hand operated until just a few years ago) to the 35th floor for a view of the city and some Seattle history. Food is available there, too. $20 adults, $16 Seniors. -

02 Pike Place Market

The Market as Organizer of an Urban CommunitY Pike Place Market, Seattle The Pike Place Market, which climbs a steep hillside not far.above the Seattle waterfront (fig. 2-1), is one of America's great urban places. Some people, hearing its name without ever having been there, might think the Pike Place Market won the Rudy Bruner Award for Excellence in the Urban Environment because it is a "festival marketplace." They would be wrong, and it is worth pointing out why. The places that developers call festival markets are shopping centers that offer food and goods in an entertaining urban setting. Festival markets have wonderful aromas, public performers, and lots of small shops. They typically have interesting views. And all these things can be found at Pike Place, which is certainly festive. But the differences between Pike Place and a festival market are profound. Unlike festival markets, the Pike Place Market is a place where people live as well as shop. Some of Pike Place's inhabitants are wealthy, but a gleater number are poor or of moderate income; they occupy new or rehabilitated apartments mainly because an effort was made to obtain government subsidies. The chain merchants that operate in festival mar- kets are not allowed at Pike Place; on the contrary, Pike Place strives to rely on independent enterprises whose owners are on the premises, making their concerns and their personalities felt. Although there are plenty of restaurants and take-out food stands at Pike Place, just as in a festival market, much of the food at Pike Place comes in a basic, less expensive form-raw, forhome consumption. -

Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Final

C-025-001 FHWA, WSDOT, and the City of Seattle appreciate receiving your comments. The project has evolved since comments were submitted in 2004, please refer to this Final EIS for information on the current alternatives. The preferred Bored Tunnel Alternative would not have a tunnel operations building near Pike Place Market. The Cut-and-Cover Tunnel Alternative does include a tunnel operations building that would be constructed on the block bounded by Pine Street, SR 99, and the Alaskan Way surface street. C-025-002 The Steinbrueck Park Lid is part of the Cut-and-Cover Tunnel Alternative in this Final EIS. The preferred Bored Tunnel Alternative and the Cut- and-Cover Tunnel Alternative would have beneficial effects on the views from the Market and Victor Steinbrueck Park, as the aerial viaduct structure that currently intervenes in the views to the west, would no longer be part of the landscape. SR 99: Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Project Final EIS - Appendix T 2010 Comments and Responses July 2011 C-025-003 There is no monitoring planned specifically for areaways in Pioneer Square or Pike Place Market since the areaways are some distance away from the bored tunnel. However, when individual building monitoring plans are developed some areaways may be included and monitored as needed. A number of Pike Place Market buildings on First Avenue and Pike Place would be routinely monitored for potential settlement. At least 5 of these buildings have areaways, which are believed to be in good condition. C-025-004 WSDOT briefed the Commission on the project in April 2011. -

SCULPTURE Title: North Totem Pole, 1984 Artist

SCULPTURE Title: North Totem Pole, 1984 Artist: James Bender Location: Victor Steinbrueck Park, corner of Western & Virginia Description: Western red cedar carved in Haida-inspired style. M. Oliver initial design. J. Bender final design and carver. Metaphorical figures of the Raven, Human, Little Human, Orca, Little Raven and Bear holding a hawk. Commissioned 1983 by architect Victor Steinbrueck. www.nwart- jpbender.com. Title: Farmer’s Pole, 1984 Artist: James Bender Location: Victor Steinbrueck Park, corner of Western & Virginia Description: Western red cedar tribute pole carved to celebrate the Market farmers. Man and a woman wear “Honored Farmer – 1984” badges . Commissioned 1983 by architect Victor Steinbrueck. Concept and design was a collaboration between Bender and Steinbrueck. www.nwart- jpbender.com. Title: Sasquatch, circa 1970’s Artist: Richard W. Beyer (1925-2012) Location: North Wall, Economy Building Atrium Description: Seven foot Sasquatch wood carving. Mythical forest creature brought well-being to local tribes. Reflects dependence on generosity and terrifying power of thick forests. Artist sold smaller versions from a market stall he had during his early career. Between 1968 and 2006, he created over 90 different sculptures for public spaces in cities throughout the country that reflect local values and lore. www.richbeyersculpture.com Title: Rachel the Piggy Bank, 1986 Artist: Georgia Gerber Location: Corner of Pike Street and Pike Place Description: Bronze mascot of Pike Place Market Foundation. Model was an old sow living near the artist’s Whidbey Island home. Each year she collects thousands of coins and bills in multiple currencies which supports the Market’s food bank, child care center, medical clinic and senior center. -

Victor Steinbrueck Papers, 1931-1986

Victor Steinbrueck papers, 1931-1986 Overview of the Collection Creator Steinbrueck, Victor Title Victor Steinbrueck papers Dates 1931-1986 (inclusive) 1931 1986 Quantity 20.32 cubic feet (23 boxes and 1 package) Collection Number Summary Papers of a professor of architecture, University of Washington. Repository University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Special Collections University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, WA 98195-2900 Telephone: 206-543-1929 Fax: 206-543-1931 [email protected] Access Restrictions Open to all users, but access to portions of the papers restricted. Contact Special Collection for more information Languages English Sponsor Funding for encoding this finding aid was partially provided through a grant awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Biographical Note Victor Steinbrueck was born in 1911 in Mandan, North Dakota and moved with his family to Washington in 1914. Steinbrueck attended the University of Washington, earning a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1935. He joined the faculty at the University of Washington in 1946 and taught until his retirement in 1976. He was the author of Seattle Cityscape (1962), Seattle Cityscape II (1973) and a collections of his drawings, Market Sketchbook (1968). Victor Steinbrueck was Seattle's best known advocate of historic preservation. He led the battle against the city's redevelopment plans for the Pike Place Market in the 1960s. In 1959, the City of Seattle, together with the Central Association of Seattle, formulated plans to obtain a Housing and Urban Development (HUD) urban renewal grant to tear down the Market and everything else between First and Western, from Union to Lenora, in order to build a high rise residential, commercial and hotel complex. -

Open House 2 VICTOR STEINBRUECK PARK ORIGINAL DESIGN the Park Is an Extension of the Market and Lively Public Space with a Tranquil View of the Sound and Mountains

OVERVIEW We are improving Victor Steinbrueck Park to preserve its legacy and signifi cance. Victor Steinbrueck Park was created in 1981 by architect and activist Victor Steinbrueck and landscape architect Rich Haag. After helping to save Pike Place Market from demolition, the two designed the park (originally named Market Park) as a place to enjoy the view and to act as an extension of Market’s social life, providing a place to gather outside. The park designers felt strongly that the park provide for all people, including disadvantaged members of our community. Victor Steinbrueck Park is an incredibly well-used and well-loved space, and over the years it has seen the effects of overuse and general wear and tear. Various elements have also been added or removed from the park over time. This project will take a holistic approach to improving the park for all. GOALS SCOPE PROCESS In 2008, City Council passed a Levy that allocated $1.6M for The scope of this project includes public outreach, design, and The design team meets regularly with numerous local “Improvements to Public Safety”. These include but are not limited construc on related to improvements outlined above. In addi on, stakeholders and park users. The design team also meets to: the park was constructed on top of a parking garage, and it has regularly with Sea le Parks & Recrea on and the Pike Place • improving sight lines into the park recently been determined that the waterproofi ng membrane Market Historical Commission, which is responsible for making • renova ng sea ng between the park and garage is failing. -

Oral History Interview with George Tsutakawa, 1983 September 8-19

Oral history interview with George Tsutakawa, 1983 September 8-19 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with George Tsutakawa on September 8, 12, 14 & 19, 1983. The interview took place in Seattle, WA, and was conducted by Martha Kingsbury for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview DATE: SEPTEMBER 8, 1983 [Tape 1; Side A] [GEORGE TSUTAKAWA reviewed the transcript and added clarification, particularly about the World War II years. His added comments with his initials are in brackets--Ed.] MARTHA KINGSBURY: George, why don't we start by talking about a lot of biographical matters. I'd like to know about your personal background, your family, your growing up in Seattle and Japan also, education. GEORGE TSUTAKAWA: Uh huh. Well, let's see now. My father was a merchant who came to Seattle in 1905, and he started a small business and eventually he gets involved in fairly large company exporting and importing American goods and Japanese goods. He, as I recall, had business in Japanese food, clothing, art goods, and all sorts of things from Japan, and then in turn he was sending lumber from the Northwest to Japan. He also dealt in scrap metal and just anything. MARTHA KINGSBURY: That he sent to Japan? GEORGE TSUTAKAWA: Yeah, he sent to Japan. -

Foldrite Template Master

SEATTLE CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL Dancing Family Fun Center City Cinema Music And Concerts - MUSIC UNDER THE STARS DANCING ‘TIL DUSK BACK TO SCHOOL BBQ WITH SOUNDERS FC Join us for movies under the stars! Pre-movie DOWNTOWN SUMMER SOUNDS Freeway Park activities start at 6 p.m. and the movie begins Freeway Park ♦ Hing Hay Park Denny Park City Hall, Denny, Freeway, Occidental Live broadcast of the performance from at dusk. Occidental Park ♦ Westlake Park BBQ, games and a backpack and school Square, and Westlake parks Benaroya Hall on 98.1 Classical KING FM. Thirteen magical evenings of free, live music and supplies giveaway. Fri., July 12 Cascade Playground Free live music at a variety of locations Bring a picnic! BBQs are available for grilling. social dancing (no experience or partner required). Saturday, Aug. 31 ♦ 11 a.m.-2 p.m. Spider-Man: Into the throughout downtown Seattle. Fridays, July 5, 12, 19, 26 ♦ 7-10 p.m. Spider Verse All programs run 6-9:30 p.m. BLOCK PARTY All programs run 12-1 p.m. SUMMER STAGE ♦ 6 p.m. - one-hour beginner lesson Cascade Playground Westlake Park Tue., July 9 City Hall Park Cascade Playground Aquaman ♦ 7 p.m. - Let the dancing begin! Free raffle, BBQ, bouncy houses and music. Fri., July 12 Denny Park Concerts in the park with talented local Visit www.danceforjoy.biz for more information Tuesday, Aug. 6 ♦ 4-8 p.m. Fri., July 19 Cascade Playground Tue., July 16 City Hall Park musicians! Up Fri., July 19 Denny Park Thu., July 11 Zydeco Hing Hay Park CASCADE KIDS DAYS Thursdays, June 13-Aug. -

Comprehensive List of Seattle Parks Bonus Feature for Discovering Seattle Parks: a Local’S Guide by Linnea Westerlind

COMPREHENSIVE LIST OF SEATTLE PARKS BONUS FEATURE FOR DISCOVERING SEATTLE PARKS: A LOCAL’S GUIDE BY LINNEA WESTERLIND Over the course of writing Discovering Seattle Parks, I visited every park in Seattle. While my guidebook describes the best 100 or so parks in the city (in bold below), this bonus feature lists all the parks in the city that are publicly owned, accessible, and worth a visit. Each park listing includes its address and top features. I skipped parks that are inaccessible (some of the city’s greenspaces have no paths or access points) and ones that are simply not worth a visit (just a square of grass in a median). This compilation also includes the best of the 149 waterfront street ends managed by the Seattle Department of Transportation that have been developed into mini parks. I did not include the more than 80 community P-Patches that are managed by the Department of Neighbor- hoods, although many are worth a visit to check out interesting garden art and peek at (but don’t touch) the garden beds bursting with veggies, herbs, and flowers. For more details, links to maps, and photos of all these parks, visit www.yearofseattleparks.com. Have fun exploring! DOWNTOWN SEATTLE & THE Kobe Terrace. 650 S. Main St. Paths, Seattle Center. 305 Harrison St. INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT city views, benches. Lawns, water feature, cultural institutions. Bell Street Park. Bell St. and 1st Ave. Lake Union Park. 860 Terry Ave. N. to Bell St. and 5th Ave. Pedestrian Waterfront, spray park, water views, Tilikum Place. 2701 5th Ave. -

Housing Choice Voucher Program

Housing Choice Voucher Program Seattle Neighborhood Guide 190 Queen Anne Ave N Seattle, WA 98109 206.239.1728 1.800.833.6388 (TDD) www.seattlehousing.org Table of Contents Introduction Introduction ..……………………………………………………. 1 Seattle is made up of many neighborhoods that offer a variety Icon Key & Walk, Bike and Transit Score Key .……. 1 of features and characteristics. The Housing Choice Voucher Crime Rating ……………………………………………………… 1 Program’s goal is to offer you and your family the choice to Seattle Map ………………………………………………………. 2 move into a neighborhood that will provide opportunities for Broadview/Bitter Lake/Northgate/Lake City …….. 3 stability and self-sufficiency. This voucher can open the door Ballard/Greenwood ………………………………………….. 5 for you to move into a neighborhood that you may not have Fremont/Wallingford/Green Lake …………………….. 6 been able to afford before. Ravenna/University District ………………………………. 7 Magnolia/Interbay/Queen Anne ………………………. 9 The Seattle Neighborhood Guide provides information and South Lake Union/Eastlake/Montlake …………….… 10 guidance to families that are interested in moving to a Capitol Hill/First Hill ………………………………………….. 11 neighborhood that may offer a broader selection of schools Central District/Yesler Terrace/Int’l District ………. 12 and more opportunities for employment. Within the Madison Valley/Madrona/Leschi ……………………... 13 Neighborhood Guide, you will find information about schools, Belltown/Downtown/Pioneer Square ………………. 14 parks, libraries, transportation and community services. Mount Baker/Columbia City/Seward Park ………… 15 While the guide provides great information, it is not Industrial District/Georgetown/Beacon Hill ……… 16 exhaustive. Learn more about your potential neighborhood Rainier Beach/Rainier Valley …………………………….. 17 by visiting the area and researching online. Delridge/South Park/West Seattle .…………………… 19 Community Resources ……………….……………………. -

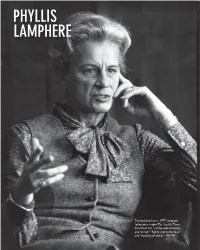

Phyllis Lamphere

PHYLLIS LAMPHERE During Lamphere’s 1977 campaign to become mayor, The Seattle Times described her “earthy sophistication and humor,” “highly expressive face,” and “mastery of words.” MOHAI CITY GIRL LEAVES BIG MARK innie Hagmoe was always inspiring her daughter Phyllis. Plucky and adventurous, Minnie became the breadwinner when her alcoholic husband went missing. Like Mher relatives, she worked for the City of Seattle, where her long career included dispensing licenses for the 1962 World’s Fair and procuring a truckload of pachyderm manure to fertilize her yard and grow “corn that summer as high as an elephant’s eye.” Her friend Emmett Watson joked in a Seattle Post-Intelligencer column that Minnie never learned the word “can’t.” She built much of her house herself and sewed her daughters’ clothes when she wasn’t working a second job to pay for their dance lessons. In her first retirement, Minnie ordered a new VW Beetle, picked it up in Switzerland and drove it around Europe and as far as India, often scooping up hitchhikers for companionship. Phyllis, who started dancing before kindergarten, grew tall and lithe. She swam across Lake Washington at 11, with her father rowing alongside. She won a scholarship to Barnard College in New York where she soaked up Broad- way plays, music at Harlem’s Apollo Theater and modern dance studying under Martha Graham. Tragedy cut in on enchantment. Her father died a vagrant while she was in college. She was widowed at 22, five months after marrying an Army officer. But like her mother, Phyllis didn’t stand still.