Hungary and the Czech Republic's Approach to Gas Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System

The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System Chi Kong Chyong, Pierre Noël and David M. Reiner September 2010 CWPE 1051 & EPRG 1026 The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System EPRG Working Paper 1026 Cambridge Working Paper in Economics 1051 Chi Kong Chyong, Pierre Noёl and David M. Reiner Abstract We calculate the total cost of building Nord Stream and compare its levelised unit transportation cost with the existing options to transport Russian gas to western Europe. We find that the unit cost of shipping through Nord Stream is clearly lower than using the Ukrainian route and is only slightly above shipping through the Yamal-Europe pipeline. Using a large-scale gas simulation model we find a positive economic value for Nord Stream under various scenarios of demand for Russian gas in Europe. We disaggregate the value of Nord Stream into project economics (cost advantage), strategic value (impact on Ukraine’s transit fee) and security of supply value (insurance against disruption of the Ukrainian transit corridor). The economic fundamentals account for the bulk of Nord Stream’s positive value in all our scenarios. Keywords Nord Stream, Russia, Europe, Ukraine, Natural gas, Pipeline, Gazprom JEL Classification L95, H43, C63 Contact [email protected] Publication September 2010 EPRG WORKING PAPER Financial Support ESRC TSEC 3 www.eprg.group.cam.ac.uk The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System1 Chi Kong Chyong* Electricity Policy Research Group (EPRG), Judge Business School, University of Cambridge (PhD Candidate) Pierre Noёl EPRG, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge David M. Reiner EPRG, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge 1. -

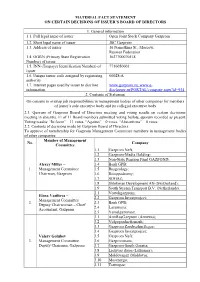

Material Fact Statement on Certain Decisions of Issuer’S Board of Directors

MATERIAL FACT STATEMENT ON CERTAIN DECISIONS OF ISSUER’S BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1. General information 1.1. Full legal name of issuer Open Joint Stock Company Gazprom 1.2. Short legal name of issuer JSC Gazprom 1.3. Address of issuer 16 Nametkina St., Moscow, Russian Federation 1.4. OGRN (Primary State Registration 1027700070518 Number) of issuer 1.5. INN (Taxpayer Identification Number) of 7736050003 issuer 1.6. Unique issuer code assigned by registering 00028-А authority 1.7. Internet pages used by issuer to disclose www.gazprom.ru; www.e- information disclosure.ru/PORTAL/company.aspx?id=934 2. Contents of Statement On consent to overlap job responsibilities in management bodies of other companies for members of issuer’s sole executive body and its collegial executive body 2.1. Quorum of Gazprom Board of Directors meeting and voting results on certain decisions: meeting in absentia, 11 of 11 Board members submitted voting ballots, quorum recorded as present. Voting results: “In favor” – 11 votes, “Against” – 0 votes, “Abstentions” – 0 votes. 2.2. Contents of decisions made by Gazprom Board of Directors: To approve of membership for Gazprom Management Committee members in management bodies of other companies: Member of Management No. Company Committee 1.1 Gazprom Neft; 1.2 Gazprom-Media Holding; 1.3 Non-State Pension Fund GAZFOND; Alexey Miller – 1.4 Bank GPB; 1. Management Committee 1.5 Rusgeology; Chairman, Gazprom 1.6 Rosippodromy; 1.7 SOGAZ; 1.8 Shtokman Development AG (Switzerland); 1.9 South Stream Transport B.V. (Netherlands). 2.1 Vostokgazprom; Elena Vasilieva – 2.2 Gazprom Investproject; Management Committee 2. -

Consolidated Financial Statements 2018

GAZPROM GERMANIA CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2018 www.gazprom-germania.de Consolidated Financial Statements 2018 GAZPROM Germania GmbH, Berlin Page 2 CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Group management report ................................................................................................................... 7 Economic and regulatory conditions ................................................................................................... 7 General economic conditions .......................................................................................................... 7 Energy policy and regulatory environment ...................................................................................... 8 Business performance ......................................................................................................................... 9 Group performance ......................................................................................................................... 9 Marketing and trading business .................................................................................................... 10 Gas storage .................................................................................................................................. -

Gazprom Germania, Gm&T and Wingas with Corporate Stand at E-World 2019

— PRESS RELEASE MORE ENERGY TOGETHER: GAZPROM GERMANIA, GM&T AND WINGAS WITH CORPORATE STAND AT E-WORLD 2019 Berlin/London/Kassel/Essen, 5 February 2019: Gazprom Marketing & Trading Ltd (GM&T) and WINGAS GmbH (WINGAS) welcome customers and counterparties to their jointly hosted stand at E-world 2019. As part of continued integration, the GAZPROM Germania Group, GM&T and WINGAS are developing commercial partnership to enhance their trading and marketing capabilities across Europe. At E-world 2019 WINGAS is presenting Customer Portal 2.0 with new transaction area for the first time. In the portal WINGAS customers will have the opportunity to exercise contractual options and to buy new products directly online. Mr. Daniel Gornig, the Director of Trading for the GAZPROM Germania Group emphasizes that: “GM&T and WINGAS’ commercial and support functions work together towards the same goals and objectives. What this last year has shown is that we are stronger together. The joint stand of GAZPROM Germania, WINGAS and GM&T is another sign of further integration of the marketing and trading activities within the Group.” Mr. Matthias Peter, the Head of the Marketing for the GAZPROM Germania Group said: “The objective of closer partnership between GM&T and WINGAS is to have a global reach while keeping a focus on the development of the important European gas markets and on the needs of every individual customer. In this context we are also continuously optimising WINGAS product and service portfolio.” E-world is Europe's largest energy trade fair and takes place from 05th till 07th February, 2019 in Essen. -

The Commercial Deals Connected with Gazprom's Nord Stream 2

The commercial deals connected with Gazprom's Nord Stream 2 A review of strings and benefits attached to the controversial Russian pipelines Anke Schmidt-Felzmann, PhD Senior Researcher at the Research Centre of the General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania Abstract This paper reviews the multiple strings and benefits attached to the single most controversial gas pipeline project in Europe - the second Russian twin subsea pipeline that is currently under construction in the Baltic Sea. While much attention has been paid to the question of why and how the Russian state- controlled energy giant seeks to circumvent Ukraine as a transit country for its delivery of gas to Western Europe, hardly any attention has been paid to the benefits gained by the companies and political entities directly involved in the preparation and construction of Nord Stream 2. The paper seeks to fill this gap in the debate by taking a closer look at the business deals and commercial actors involved in the implementation of this second Russian natural gas pipeline project in the Baltic Sea. It highlights how local and national economic interests and European energy companies' motivations for participating in the project go beyond the volumes of Russian natural gas that Gazprom expects to deliver to European customers through its Baltic Sea pipelines from 2020. Keywords: Baltic Sea, Nord Stream, Gazprom, Russia, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Latvia. This analysis was produced within the Think Visegrad Non-V4 Fellowship programme. Think Visegrad – V4 Think Tank Platform is a network for structured dialog on issues of strategic regional importance. The network analyses key issues for the Visegrad Group, and provides recommendations to the governments of V4 countries, the annual presidencies of the group, and the International Visegrad Fund. -

Case COMP/M.6910 — Gazprom/Wintershall/Target Companies) (Text with EEA Relevance) (2013/C 321/07)

7.11.2013 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 321/7 Prior notification of a concentration (Case COMP/M.6910 — Gazprom/Wintershall/Target Companies) (Text with EEA relevance) (2013/C 321/07) 1. On 30 October 2013 the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 ( 1 ), concerning a swap of certain assets between JSC Gazprom (‘Gazprom’) and Wintershall Holding GmbH (‘Wintershall’) pursuant to a Basic Swap Agreement dated November 14, 2012. Under the Agreement, in exchange for minority interests in certain of its natural gas and gas condensate exploration and production assets in Western Siberia, Gazprom will acquire from Wintershall: (1) sole control of Wingas GmbH (‘Wingas’) and Wintershall Erdgas Handelshaus GmbH & Co. KG (‘WIEH’), two natural gas supply and storage joint ventures formed and jointly controlled by Wintershall and Gazprom, and (2) joint control of Wintershall Noordzee BV (‘WINZ’) and Wintershall Services BV (‘Wintershall Services’), two wholly owned Wintershall subsidiaries engaged in relatively minor oil and gas exploration and production activities in the North Sea. The proposed acquisitions are interdependent and therefore constitute a single concentration within the meaning of Regulation (EC) No 139/2004. 2. The business activities of the undertakings concerned are: — Gazprom is active in the exploration, production, transportation, supply, trading, distribution, and storage of natural gas, — Wintershall, owned by BASF SE (‘BASF’), engages in the exploration and production of crude oil and natural gas in particular in Europe, Northern Africa, South America and Russia, as well as in natural gas pipeline operation, investment and natural gas supply and storage, — Wintershall and Gazprom also jointly own and control a German gas transmission business, which is conducted through the transmission operators GASCADE Gastransport GmbH, OPAL Gastransport GmbH & Co. -

WINGAS Fibre-Optic Cables

MORE ENERGY FOR YOUR FUTURE. More energy for your future. The energy supply of the future is a key concern in today's society. How will we meet our ener- gy needs reliably and affordably, both today and tomorrow? When it comes to protecting the climate, how can we achieve quicker progress and greater efficiency? What technologies and fuels should be used in the future? The path towards a CO2-free energy landscape is clearly outlined, but we are still a long way off from being able to meet future demand with renewable energies on a similar scale and with the same reliability as we can with conventional energy sources. It is clear that the journey to the energy of the future will be a difficult one. We will all need to show vision, strength and persistence. However, the right framework is also needed so that the energy industry can adapt to future requirements. In other words, we need an energy policy with the courage to see sense – after all, clear CO2 reduction targets that take supply security and affordability into account are needed if we are to sensibly protect the climate. This will only be possible if conventional fuels and renewables are coupled together to optimise CO2 emissions. Fortunately, many people are realising that natural gas can play a key role in a sustainable energy supply. Natural gas is the most environmentally friendly among conventional energy sources, with a high level of supply security. Natural gas will therefore have to play a central role in the energy landscape of the future – with efficient technologies in all sectors, wether as a system partner to renewables in the heating market, as an important backup in electricity production or as a clean alternative fuel for mobility purposes; after all, electric vehicles alone will not achieve a mobility revolution in the medium to long term. -

Czech Republic in 2017

National Report of the Energy Regulatory Office on the Electricity and Gas Industries in the Czech Republic in 2017 July 2018 National Report of the Energy Regulatory Office on the Electricity and Gas Industries in the Czech Republic in 2017 List of frequent abbreviations and acronyms ACER Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators CEER Council of European Energy Regulators ČR, CZ, CR Czech Republic EC, Commission European Commission Energy Act Act No 458/2000 on conditions of business and state administration in energy industries and amending certain laws EP European Parliament ERO, Office Energy Regulatory Office EC European Community EU, Union European Union market operator, OTE, a.s. OTE, a.s., the market operator PCI Projects of Common Interest REMIT Regulation (EU) No 1227/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on wholesale energy market integrity and transparency TYNDP Ten Year Network Development Plan V4 The Visegrád Four 1 National Report of the Energy Regulatory Office on the Electricity and Gas Industries in the Czech Republic in 2017 Content 1 Foreword by the ERO Board .............................................................................. 3 2 Main developments in the electricity and gas markets....................................... 4 3 The electricity market......................................................................................... 6 3.1 Network regulation............................................................................................. 6 3.1.1 Unbundling........................................................................................................ -

CEE GRIP Annex a : Country Profiles

Cluden Halmstad CEE GRIP Annex A : Country Profiles January 2012 2 Introduction - Content Introduction The following Country Profiles provide an overview of the existing gas infrastructure in each of the CEE GRIP countries as of November 2011. In case of Germany, only observing TSOs are included. Most of the information was supplied by the respective TSOs. The overview of Current Publication indicates the specific reports such as National Development Plan, Winter or Summer Outlook which are published by the respective TSO. Content Austria ...................................................................................................................................................................................3 Bulgaria ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Czech Republic ...............................................................................................................................................................12 Germany ...........................................................................................................................................................................15 Hungary ............................................................................................................................................................................18 -

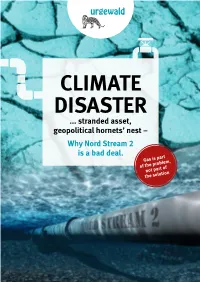

Nord Stream 2

urgewald CLIMATE DISASTER ... stranded asset, geopolitical hornets’ nest – Why Nord Stream 2 is a bad deal. Gas is part of the problem, not part of the solution Content 1. Executive summary ................................................... 3 2. The interests behind Nord Stream 2 ..................................... 4 3. The companies behind Nord Stream 2 .................................... 6 3.1 The company behind the pipeline: Gazprom ...........................7 3.2 A perfect partner: Wintershall Dea ....................................8 3.3 The other German player: Uniper .....................................9 3.4 The new producer in Siberia: OMV ..................................10 3.5 Expanding its business in Russia: Shell ..............................11 3.6 The big French gas player: Engie ....................................12 4. Where the gas comes from: Devastating effects on Indigenous livelihoods and the environment in Yamal ............................... 13 FAQ: Unpacking the industry’s lies about the need for Nord Stream 2. 16 Cover: ©iStock_Ladislav Kubeš, Shutterstock_Ksanawo Kubeš, ©iStock_Ladislav Cover: 2 1. Executive summary Nord Stream 2 is part of a system of underwater pipelines This briefing paper outlines the involvement of Nord in the Baltic Sea intended to transport gas over 1200 km Stream 2 AG owner Gazprom and the five financiers of the from Russia to Germany. The pipeline would connect gas project: Wintershall Dea, Uniper, OMV, Shell, and Engie. facilities in Ust-Luga in the Leningrad region with a termi- All of these companies either have long-term contracts nal in Lubmin, a small town on Germany’s Northeastern with Gazprom or joint gas and oil operations in Russia, coast. Nord Stream 2 is disastrous for the climate and not some of which lie in gas fields that will feed Nord Stream 2. -

PJSC Gazprom Environmental Report 2016 1

PJSC Gazprom Environmental Report 2016 1 The Power Within Годовой отчет ПАО «Газпром» за 2016 год 1 PJSC Gazprom Annual Report 2016 PJSC Gazprom Environmental Report 2016 Letter of Deputy Chairman 5 of PJSC Gazprom Management Committee 5 Introduction 6 Environmental protection management 8 Environmental management system 8 Environmental targets and programs 11 Financing of environmental protection 12 Adverse environmental impact fee 16 Environmental performance and energy saving 20 Air protection 20 Greenhouse gas emissions 25 Utilization of associated petroleum gas 27 Reduction of vehicle fleet impact on air 28 Water use and protection of water resources 32 Production and consumption waste management 34 Land and soil protection 38 Protection of biodiversity 40 Energy saving 44 Use of renewable and secondary sources of energy 49 Parameters of environmental activity and environmental impact 50 of PJSC Gazprom abroad Preventing negative impact on the environment 56 Environmental assessment of projects 56 Operational environmental monitoring and control 57 Prevention of accidents 60 Environmental risk insurance 61 State environmental supervision 62 Scientific and technical support of environment 63 protection Scientific research and development 63 Implementation of innovative environment protection 64 technologies Gazprom prize in science and technical engineering 65 International cooperation 68 Information disclosure 69 Voluntary environmental activities 71 Conclusion 74 Glossary of main terms and abbreviations 75 Addresses and contacts -

BASF AG List of Shares Held 2003

List of Shares Held 2003 Contents 2 I. Fully, proportionally and equity consolidated subsidiaries and affiliates accounted for in the Consolidated Financial Statements 21.Fully consolidated subsidiaries (Section 290, Paragraph 2 of the German Commercial Code) 2 • Germany 3 • Europe (excluding Germany) 6 • North America 7 • South America 7 • Asia, Pacific Area, Africa 92.Proportionally consolidated affiliates (Section 310 of the German Commercial Code) 9 • Germany 9 • Europe (excluding Germany) 9 • South America 9 • Asia, Pacific Area, Africa 93.Equity consolidated subsidiaries (Section 312 of the German Commercial Code) 9 • Germany 10 • Europe (excluding Germany) 10 • South America 11 • Asia, Pacific Area, Africa 11 4. Equity consolidated affiliates (Section 312 of the German Commercial Code) 11 • Germany 11 • Europe (excluding Germany) 12 II. Other subsidiaries, affiliates and other participating interests 12 1. Non-consolidated minor subsidiaries (Section 296 [2] of the German Commercial Code) 12 • Germany 14 • Europe (excluding Germany) 17 • North America 17 • South America 18 • Asia, Pacific Area, Africa 20 2. Non-consolidated minor affiliates (Section 311 [2] of the German Commercial Code) 27 3. Participating interests of between 5 and 20 percent in major corporations (Section 285, No. 11 of the German Commercial Code) 27 • Germany 28 III. Information on subsidiaries (exemptions under Section 264, Paragraph 3 and Section 264 b of the German Commercial Code) 28 • Germany BASF – List of Shares Held 2003 1 BASF Group and BASF Aktiengesellschaft List of Shares Held 2003 Pursuant to Section 313, Paragraph 2 and Section 285, No. 11 of the German Commercial Code I. Fully, proportionally and equity consolidated subsidiaries and affiliates accounted for in the Consolidated Financial Statements 1.