Eye Movements and Vestibular Function in Critical Care, Emergency, and Ambulatory Neurology (Level 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pearls: Infectious Diseases

Pearls: Infectious Diseases Karen L. Roos, M.D.1 ABSTRACT Neurologists have a great deal of knowledge of the classic signs of central nervous system infectious diseases. After years of taking care of patients with infectious diseases, several symptoms, signs, and cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities have been identified that are helpful time and time again in determining the etiological agent. These lessons, learned at the bedside, are reviewed in this article. KEYWORDS: Herpes simplex virus, Lyme disease, meningitis, viral encephalitis CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS does not have an altered level of consciousness, sei- zures, or focal neurologic deficits. Although the ‘‘classic triad’’ of bacterial meningitis is The rash of a viral exanthema typically involves the fever, headache, and nuchal rigidity, vomiting is a face and chest first then spreads to the arms and legs. common early symptom. Suspect bacterial meningitis This can be an important clue in the patient with in the patient with fever, headache, lethargy, and headache, fever, and stiff neck that the meningitis is vomiting (without diarrhea). Patients may also com- due to echovirus or coxsackievirus. plain of photophobia. An altered level of conscious- Suspect tuberculous meningitis in the patient with ness that begins with lethargy and progresses to stupor either several weeks of headache, fever, and night during the emergency evaluation of the patient is sweats or a fulminant presentation with fever, altered characteristic of bacterial meningitis. mental status, and focal neurologic deficits. Fever (temperature 388C[100.48F]) is present in An Ixodes tick must be attached to the skin for at least 84% of adults with bacterial meningitis and in 80 to 24 hours to transmit infection with the spirochete 1–3 94% of children with bacterial meningitis. -

Acquired Aphasia in Children

13 Acquired Aphasia in Children DOROTHY M. ARAM Introduction Children versus Adults Language disruptions secondary to acquired central nervous system (CNS) lesions differ between children and adults in multiple respects. Chief among these differences are the developmental stage of language ac- quisition at the time of insult and the developmental stage of the CNS. In adult aphasia premorbid mastery of language is assumed, at least to the level of the aphasic's intellectual ability and educational opportunities. Acquired aphasia sustained in childhood, however, interferes with the de- velopmental process of language learning and disrupts those aspects of language already mastered. The investigator and clinician thus are faced with sorting which aspects of language have been lost or impaired from those yet to emerge, potentially in an altered manner. Complicating re- search and clinical practice in this area is the need to account continually for the developmental stage of that aspect of language under consideration for each child. In research, stage-appropriate language tasks must be se- lected, and comparison must be made to peers of comparable age and lan- guage stage. Also, appropriate controls common in adult studies, such as social class and gender, are critical. These requirements present no small challenge, as most studies involve a wide age range of children and ado- lescents. In clinical practice, the question is whether assessment tools used for developmental language disorders should be used or whether adult aphasia batteries should be adapted for children. The answer typically de- pends on the age of the child and the availability of age- and stage-appro- 451 ACQUIRED APHASIA, THIRD EDITION Copyright 1998 by Academic Press. -

Synchronized Babinski and Chaddock Signs Preceded the MRI Findings in a Case of Repetitive Transient Ischemic Attack

□ CASE REPORT □ Synchronized Babinski and Chaddock Signs Preceded the MRI Findings in a Case of Repetitive Transient Ischemic Attack Kosuke Matsuzono 1,2, Takao Yoshiki 1, Yosuke Wakutani 1, Yasuhiro Manabe 3, Toru Yamashita 2, Kentaro Deguchi 2, Yoshio Ikeda 2 and Koji Abe 2 Abstract We herein report a 53-year-old female with repeated transient ischemic attack (TIA) symptoms including 13 instances of right hemiparesis that decreased in duration over 4 days. Two separate examinations using diffusion weighted image (DWI) in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed normal findings, but we ob- served that both Babinski and Chaddock signs were completely synchronized with her right hemiparesis. We were only able to diagnose this case of early stage TIA using clinical signs. This diagnosis was confirmed 4 days after the onset by the presence of abnormalities on the MRI. DWI-MRI is generally useful when diag- nosing TIA, but a neurological examination may be more sensitive, especially in the early stages. Key words: Babinski sign, Chaddock sign, TIA, diffusion weighted image (Intern Med 52: 2127-2129, 2013) (DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0190) Introduction Case Report Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a clinical syndrome A 53-year-old woman suddenly developed right hemipare- that consists of sudden focal neurologic signs and a com- sis, and she was admitted to our hospital 30 minutes after plete recovery usually within 24 hours (1). Because TIA can the onset. She had smoked 10 cigarettes daily for 23 years, sometimes develop into a cerebral infarction, an early diag- and quit at 43 years of age. -

Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders

CHAPTER 19 Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders David S. Zee and David Newman-Toker OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF THE MEDULLA THE SUPERIOR COLLICULUS Wallenberg’s Syndrome (Lateral Medullary Infarction) OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF Syndrome of the Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery THE THALAMUS Skew Deviation and the Ocular Tilt Reaction OCULAR MOTOR ABNORMALITIES AND DISEASES OF THE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN BASAL GANGLIA THE CEREBELLUM Parkinson’s Disease Location of Lesions and Their Manifestations Huntington’s Disease Etiologies Other Diseases of Basal Ganglia OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN THE PONS THE CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES Lesions of the Internuclear System: Internuclear Acute Lesions Ophthalmoplegia Persistent Deficits Caused by Large Unilateral Lesions Lesions of the Abducens Nucleus Focal Lesions Lesions of the Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation Ocular Motor Apraxia Combined Unilateral Conjugate Gaze Palsy and Internuclear Abnormal Eye Movements and Dementia Ophthalmoplegia (One-and-a-Half Syndrome) Ocular Motor Manifestations of Seizures Slow Saccades from Pontine Lesions Eye Movements in Stupor and Coma Saccadic Oscillations from Pontine Lesions OCULAR MOTOR DYSFUNCTION AND MULTIPLE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN SCLEROSIS THE MESENCEPHALON OCULAR MOTOR MANIFESTATIONS OF SOME METABOLIC Sites and Manifestations of Lesions DISORDERS Neurologic Disorders that Primarily Affect the Mesencephalon EFFECTS OF DRUGS ON EYE MOVEMENTS In this chapter, we survey clinicopathologic correlations proach, although we also discuss certain metabolic, infec- for supranuclear ocular motor disorders. The presentation tious, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases in which su- follows the schema of the 1999 text by Leigh and Zee (1), pranuclear and internuclear disorders of eye movements are and the material in this chapter is intended to complement prominent. -

Eye Movement Disorders and Neurological Symptoms in Late-Onset Inborn Errors of Metabolism Koens, Lisette H.; Tijssen, Marina A

University of Groningen Eye movement disorders and neurological symptoms in late-onset inborn errors of metabolism Koens, Lisette H.; Tijssen, Marina A. J.; Lange, Fiete; Wolffenbuttel, Bruce H. R.; Rufa, Alessandra; Zee, David S.; de Koning, Tom J. Published in: Movement Disorders DOI: 10.1002/mds.27484 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Koens, L. H., Tijssen, M. A. J., Lange, F., Wolffenbuttel, B. H. R., Rufa, A., Zee, D. S., & de Koning, T. J. (2018). Eye movement disorders and neurological symptoms in late-onset inborn errors of metabolism. Movement Disorders, 33(12), 1844-1856. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.27484 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

UCSD Moores Cancer Center Neuro-Oncology Program

UCSD Moores Cancer Center Neuro-Oncology Program Recent Progress in Brain Tumors 6DQWRVK.HVDUL0'3K' 'LUHFWRU1HXUR2QFRORJ\ 3URIHVVRURI1HXURVFLHQFHV 0RRUHV&DQFHU&HQWHU 8QLYHUVLW\RI&DOLIRUQLD6DQ'LHJR “Brain Cancer for Life” Juvenile Pilocytic Astrocytoma Metastatic Brain Cancer Glioblastoma Multiforme Glioblastoma Multiforme Desmoplastic Infantile Ganglioglioma Desmoplastic Variant Astrocytoma Medulloblastoma Atypical Teratoid Rhabdoid Tumor Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma -Mutational analysis, microarray expression, epigenetic phenomenology -Age-specific biology of brain cancer -Is there an overlap? ? Neuroimmunology ? Stem cell hypothesis Courtesy of Dr. John Crawford Late Effects Long term effect of chemotherapy and radiation on neurocognition Risks of secondary malignancy secondary to chemotherapy and/or radiation Neurovascular long term effects: stroke, moya moya Courtesy of Dr. John Crawford Importance Increase in aging population with increased incidence of cancer Patients with cancer living longer and developing neurologic disorders due to nervous system relapse or toxicity from treatments Overview Introduction Clinical Presentation Primary Brain Tumors Metastatic Brain Tumors Leptomeningeal Metastases Primary CNS Lymphoma Paraneoplastic Syndromes Classification of Brain Tumors Tumors of Neuroepithelial Tissue Glial tumors (astrocytic, oligodendroglial, mixed) Neuronal and mixed neuronal-glial tumors Neuroblastic tumors Pineal parenchymal tumors Embryonal tumors Tumors of Peripheral Nerves Shwannoma Neurofibroma -

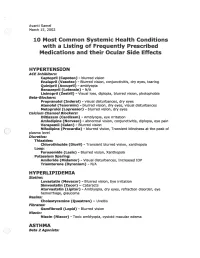

2002 Samel 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with A

Avanti Samel / March 15, 2002 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with a Listing of Frequently Prescribed Medications and their Ocular Side Effects HYPERTENSION ACE Inhibitors: Captopril (Capoten}- blurred vision Enalapril (Vasotec) - Blurred vision, conjunctivitis, dry eyes, tearing Quinipril (Accupril)- amblyopia Benazepril (Lotensin)- N/A Lisinopril (Zestril) - Visual loss, diplopia, blurred vision, photophobia Beta-Blockers: Propranolol (Inderal)- visual disturbances, dry eyes Atenolol (Tenormin)- blurred vision, dry eyes, visual disturbances Metoprolol (Lopressor) - blurred vision, dry eyes calcium Channel Blockers: Diltiazem (Cardizem)- Amblyopia, eye irritation Amlodipine (Norvasc)- abnormal vision, conjunctivitis, diplopia, eye pain Verapamil (Calan)- Blurred vision Nifedipine (Procardia) - blurred vision, Transient blindness at the peak of plasma level · Diuretics: Thiazides: Chlorothiazide (Diuril) - Transient blurred vision, xanthopsia Loop: Furosemide (Lasix) - Blurred vision, Xanthopsia Potassium Sparing: Amiloride (Midamor) - Visual disturbances, Increased lOP Triamterene (Dyrenium)- N/A HYPERLIPIDEMIA Statins: Lovastatin (Mevacor) - Blurred vision, Eye irritation Simvastatin (Zocor)- Cataracts Atorvastatin (Lipitor)- Amblyopia, dry eyes, refraction disorder, eye hemorrhage, glaucoma Resins: Cholestyramine (Questran)- Uveitis Fibrates: Gemfibrozil (Lopid)- Blurred vision Niacin: Niacin (Niacor) - Toxic amblyopia, cystoid macular edema ASTHMA ( ) Beta 2 Agonists: Albuterol (Proventil) - N/A ( Salmeterol (Serevent)- -

Clinical Characteristics and Prognostic Factors in Childhood

BALKAN MEDICAL JOURNAL 80 THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRAKYA UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF MEDICINE © Trakya University Faculty of Medicine Balkan Med J 2013; 30: 80-4 • DOI: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2012.092 Available at www.balkanmedicaljournal.org Original Article Clinical Characteristics and Prognostic Factors in Childhood Bacterial Meningitis: A Multicenter Study Özden Türel1, Canan Yıldırım2, Yüksel Yılmaz2, Sezer Külekçi3, Ferda Akdaş3, Mustafa Bakır1 1Department of Pediatrics, Section of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Marmara University, İstanbul, Turkey 2Department of Pediatrics, Section of Pediatric Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Marmara University, İstanbul, Turkey 3Department of Audiology, Faculty of Medicine, Marmara University, İstanbul, Turkey İstanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT Objective: To evaluate clinical features and sequela in children with acute bacterial meningitis (ABM). Study Design: Multicenter retrospective study. Material and Methods: Study includes retrospective chart review of children hospitalised with ABM at 11 hospitals in İstanbul during 2005. Follow up visits were conducted for neurologic examination, hearing evaluation and neurodevelopmental tests. Results: Two hundred and eighty three children were included in the study. Median age was 12 months and 68.6% of patients were male. Almost all patients had fever at presentation (97%). Patients younger than 6 months tended to present with feeding difficulties (84%), while patients older than 24 months were more likely to present with vomitting (93%) and meningeal signs (84%). Seizures were present in 65 (23%) patients. 26% of patients were determined to have at least one major sequela. The most common sequelae were speech or language problems (14.5%). 6 patients were severely disabled because of meningitis. Presence of focal neurologic signs at presentation and turbid cerebrospinal fluid appearance increased sequelae signifi- cantly. -

Neuro-Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Paraneoplastic Syndromes

STATE OF THE ART Neuro-Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Paraneoplastic Syndromes Melissa W. Ko, MD, Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, and Steven L. Galetta, MD Abstract: Paraneoplastic syndromes with neuro- PARANEOPLASTIC CEREBELLAR ophthalmologic manifestations may involve the cen DEGENERATION tral nervous system, cranial nerves, neuromuscular Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) is junction, optic nerve, uvea, or retina. Most of these a syndrome of subacute severe pancerebellar dysfunction disorders are related to immunologic mechanisms (Table 1). Initially, patients present with gait instability. presumably triggered by the neoplastic expression of Over several days to weeks, they develop truncal and limb neuronal proteins. Accurate recognition is essential to ataxia, dysarthria, and dysphagia. The cerebellar disease appropriate management. eventually stabilizes but leaves patients incapacitated. PCD is most commonly associated with cancers of (/Neuro-Ophthalmol 2008;28:58-68) the lung, ovary, and breast and with Hodgkin disease (7). Ocular motor manifestations include nystagmus, ocular dysmetria, saccadic pursuit, saccadic intrusions and he term "paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome" (PNS) oscillations, and skew deviation (8). Over the last 30 refers to dysfunction of the nervous system caused by T years, at least nine anti-neuronal antibodies have been a benign or malignant tumor via mechanisms other than associated with PCD. However, only about 50% of patients metastasis, coagulopathy, infection, or treatment side with suspected PCD test positive for anti-neuronal anti effects (1). Whereas reports of possible paraneoplastic bodies in serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (9). Anti-Yo neuropathies extend back to the 19th century, cerebellar syndromes associated with cancer were first described by and anti-Tr are the autoantibodies most commonly Brouwerin 1919 (2). -

GAZE and AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1)

GAZE AND AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1) Gaze and Autonomic Innervation Disorders Last updated: May 9, 2019 PUPILLARY SYNDROMES ......................................................................................................................... 1 ANISOCORIA .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Benign / Non-neurologic Anisocoria ............................................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Preganglionic .......................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Postganglionic ........................................................................ 2 Horner Syndrome ............................................................................................................................. 2 Etiology of Horner syndrome ................................................................................................ 2 Localizing Tests .................................................................................................................... 2 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................... 3 Flow diagram for workup of anisocoria ........................................................................................... 3 LIGHT-NEAR DISSOCIATION ................................................................................................................. -

Psychotropic Drugs and Ocular Side Effects Psikotropik İlaçlar Ve Oküler Yan Etkileri

DOI: 10.4274/tjo.43.67944 Review / Derleme Psychotropic Drugs and Ocular Side Effects Psikotropik İlaçlar ve Oküler Yan Etkileri İpek Sönmez, Ümit Aykan* Near East University, Department of Psychiatry, Nicosia, TRNC, MD *Near East University, Department of Ophthalmology, Nicosia, TRNC Sum mary Nowadays the number of patients using the types of drugs in question here has significantly increased. A study carried out in relation with the long term use of psychotropic drugs shows that the consumption of this group of drugs has substantially increased in terms of variety and quantity. This compilation is arranged in accordance with the ocular complications of psychotropic drugs in long term treatment profile of numerous patients to the results of related literature review. If the doctor and the patients are informed about the eye problems related to the use of psychotropic drugs, potential ocular complications can be easily prevented, supervised and controlled and can even be reversed. (Turk J Ophthalmol 2013; 43: 270-7) Key Words: Psychotropic drugs, ocular, side effects, adverse effects Özet Günümüzde kronik ilaç kullanan hasta sayısı önemli derecede artmıştır. Uzun süreli psikotrop ilaç kullanımı açısından yapılan bir çalışma, hem çeşitlilik hem de miktar açısından bu grup ilaç tüketiminin önemli derecede arttığını göstermektedir. Bu derleme günümüzde çok sayıda hastanın uzun süreli tedavi profilinde yer alan psikotrop ilaçların oküler komplikasyonlarına ilişkin literatür taraması sonucu hazırlanmıştır. Hekim ve hastalar psikotrop ilaç kullanımına bağlı göz problemleri açısından bilgili oldukları takdirde potansiyel oküler komplikasyonlar kolayca önlenebilir, gözlem ve kontrol altına alınabilir ve hatta geriye döndürülebilirler. (Turk J Ophthalmol 2013; 43: 270-7) Anah tar Ke li me ler: Psikotropik ilaç, oküler, yan etki, ters etki Introduction human eye becoming sensitive to psychotropic treatments. -

Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)? Thioridazine (Mellaril) Tamoxifen

1 Q Systemic drugs and ocular toxicity: Matching Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)? Blue tinting of vision Retinopathy rare at Thioridazine (Mellaril) doses <800 mg/d Tamoxifen Blair Witch cataract Iritis, hypotony can Sildenafil (Viagra) develop Cidofovir Causes a crystalline retinopathy Isotretinoin (Accutane) Causes nyctalopia Rifabutin Yellow tinting of vision Digitalis Causes uveitis with hypopyon (Start with chlorpromazine and work down the list) 2 A Systemic drugs and retinalocular toxicity: Matching Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) Blue tinting of vision Retinopathy rare at Thioridazine (Mellaril) doses <800 mg/d Tamoxifen Blair Witch cataract Iritis, hypotony can Sildenafil (Viagra) develop Cidofovir Causes a crystalline retinopathy Isotretinoin (Accutane) Causes nyctalopia Rifabutin Yellow tinting of vision Digitalis Causes uveitis with hypopyon 3 Systemic drugs and ocular toxicity: Matching Chlorpromazine: Blair Witch cataract 4 Q Systemic drugs and retinalocular toxicity: Matching Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) Blue tinting of vision Retinopathy rare at ThioridazineWhat class of medicine (isMellaril chlorpromazine?) It is a phenothiazine doses <800 mg/d TamoxifenWhat sort of med are phenothiazines? Blair Witch cataract They are neuroleptics (but have other uses as well) Iritis, hypotony can Sildenafil (Viagra) In addition to cataracts, what ophthalmic effects does develop high-dose chlorpromazine therapy have? CidofovirIt causes pigmentation of the lids and conj Causes a crystalline retinopathy IsotretinoinWhat