Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo David Solomon, MD, Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migraine Associated Vertigo

Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain VC 2015 American Headache Society Published by JohnWiley & Sons, Inc. doi: 10.1111/head.12704 Headache Toolbox Migraine Associated Vertigo Between 30 and 50% of migraineurs will sometimes times a condition similar to benign positional vertigo experience dizziness, a sense of spinning, or feeling like called vestibular neuronitis (or vestibular neuritis/labyrinthi- their balance is off in the midst of their headaches. This is tis) is triggered by a viral infection of the inner ear, result- now termed vestibular migraine, but is also called ing in constant vertigo or unsteadiness. Symptoms can migraine associated vertigo. Sometimes migraineurs last for a few days to a few weeks and then go away as experience these symptoms before the headache, but mysteriously as they came on. Vestibular migraine, by they can occur during the headache, or even without any definition, should have migraine symptoms in at least head pain. In children, vertigo may be a precursor to 50% of the vertigo episodes, and these include head migraines developing in the teens or adulthood. Migraine pain, light and noise sensitivity, and nausea. associated vertigo may be more common in those with There are red flags, which are warning signs that ver- motion sickness. tigo is not part of a migraine. Sudden hearing loss can be For some patients this vertiginous sensation resem- the sign of an infection that needs treatment. Loss of bal- bles migraine aura, which is a reversible, relatively short- ance alone, or accompanied by weakness can be the lived neurologic symptom associated with their migraines. -

Consultation Diagnoses and Procedures Billed Among Recent Graduates Practicing General Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surger

Eskander et al. Journal of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery (2018) 47:47 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-018-0293-8 ORIGINALRESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Consultation diagnoses and procedures billed among recent graduates practicing general otolaryngology – head & neck surgery in Ontario, Canada Antoine Eskander1,2,3* , Paolo Campisi4, Ian J. Witterick5 and David D. Pothier6 Abstract Background: An analysis of the scope of practice of recent Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (OHNS) graduates working as general otolaryngologists has not been previously performed. As Canadian OHNS residency programs implement competency-based training strategies, this data may be used to align residency curricula with the clinical and surgical practice of recent graduates. Methods: Ontario billing data were used to identify the most common diagnostic and procedure codes used by general otolaryngologists issued a billing number between 2006 and 2012. The codes were categorized by OHNS subspecialty. Practitioners with a narrow range of procedure codes or a high rate of complex procedure codes, were deemed subspecialists and therefore excluded. Results: There were 108 recent graduates in a general practice identified. The most common diagnostic codes assigned to consultation billings were categorized as ‘otology’ (42%), ‘general otolaryngology’ (35%), ‘rhinology’ (17%) and ‘head and neck’ (4%). The most common procedure codes were categorized as ‘general otolaryngology’ (45%), ‘otology’ (23%), ‘head and neck’ (13%) and ‘rhinology’ (9%). The top 5 procedures were nasolaryngoscopy, ear microdebridement, myringotomy with insertion of ventilation tube, tonsillectomy, and turbinate reduction. Although otology encompassed a large proportion of procedures billed, tympanoplasty and mastoidectomy were surprisingly uncommon. Conclusion: This is the first study to analyze the nature of the clinical and surgical cases managed by recent OHNS graduates. -

Balancing Everything out Fifteen Years of Research Into Dizziness, Balance and the Pathology of Ménière’S Disease

Making It Better Balancing Everything Out Fifteen years of research into dizziness, balance and the pathology of Ménière’s disease The Ménière’s Society The Page 1 www.menieres.org.ukMénière’s Society Making It Better Index of References and Sources Further details of the reference sources and research projects discussed in this paper can be found at the following locations: V Osei -Lah, B Ceranic and L M Luxon (2008). Kirby, S.E. and Yardley, L. (2009) Clinical value of tone burst vestibular evoked The contribution of symptoms of post-traumatic myogenic potentials at threshold in acute stress disorder (PTSD), health anxiety and and stable Ménière’s disease. The Journal intolerance of uncertainty to distress in Ménière’s of Laryngology & Otology, 122, pp 452 457 disease. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, doi:10.1017/S0022215107009152 197,(5), 324-329 www.journals.cambridge.org/action/ www.eprints.soton.ac.uk/54655 displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=1850772 Yardley L., Dibb B. and Osborne G. (2003) A W Morrison, M E S Bailey and G A J Morrison Factors associated with quality of life in Meniere’s (2009). Familial Ménière’s disease: clinical and disease. Clinical Otolaryngology, 28, (5), 436-441. genetic aspects. The Journal of Laryngology (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2273.2003.00740.x). & Otology, 123, pp 29-37. doi:10.1017/S0022215108002788. Yardley L, Kirby S. Evaluation of booklet-based www.journals.cambridge.org/action/ self-management of symptoms in Ménière’s displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=3107936 disease: a randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med 2006;68:762–9 Clinical and cost effectiveness Sandhu, J. -

Eardrum Regeneration: Membrane Repair

OUTLINE Watch an animation at: Infographic: go.nature.com/2smjfq8 Pages S6–S7 EARDRUM REGENERATION: MEMBRANE REPAIR Can tissue engineering provide a cheap and convenient alternative to surgery for eardrum repair? DIANA GRADINARU he eardrum, or tympanic membrane, forms the interface between the outside world and the delicate bony structures Tof the middle ear — the ossicles — that conduct sound vibrations to the inner ear. At just a fraction of a millimetre thick and held under tension, the membrane is perfectly adapted to transmit even the faintest of vibrations. But the qualities that make the eardrum such a good conductor of sound come at a price: fra- gility. Burst eardrums are a major cause of conductive hearing loss — when sounds can’t pass from the outer to the inner ear. Most burst eardrums are caused by infections or trauma. The vast majority heal on their own in about ten days, but for a small proportion of people the perforation fails to heal natu- rally. These chronic ruptures cause conductive hearing loss and group (S. Kanemaru et al. Otol. Neurotol. 32, 1218–1223; 2011). increase the risk of middle ear infections, which can have serious In a commentary in the same journal, Robert Jackler, a head complications. and neck surgeon at Stanford University, California, wrote that, Surgical intervention is the only option for people with ear- should the results be replicated, the procedure represents “poten- drums that won’t heal. Tympanoplasty involves collecting graft tially the greatest advance in otology since the invention of the material from the patient to use as a patch over the perforation. -

Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders

CHAPTER 19 Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders David S. Zee and David Newman-Toker OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF THE MEDULLA THE SUPERIOR COLLICULUS Wallenberg’s Syndrome (Lateral Medullary Infarction) OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF Syndrome of the Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery THE THALAMUS Skew Deviation and the Ocular Tilt Reaction OCULAR MOTOR ABNORMALITIES AND DISEASES OF THE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN BASAL GANGLIA THE CEREBELLUM Parkinson’s Disease Location of Lesions and Their Manifestations Huntington’s Disease Etiologies Other Diseases of Basal Ganglia OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN THE PONS THE CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES Lesions of the Internuclear System: Internuclear Acute Lesions Ophthalmoplegia Persistent Deficits Caused by Large Unilateral Lesions Lesions of the Abducens Nucleus Focal Lesions Lesions of the Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation Ocular Motor Apraxia Combined Unilateral Conjugate Gaze Palsy and Internuclear Abnormal Eye Movements and Dementia Ophthalmoplegia (One-and-a-Half Syndrome) Ocular Motor Manifestations of Seizures Slow Saccades from Pontine Lesions Eye Movements in Stupor and Coma Saccadic Oscillations from Pontine Lesions OCULAR MOTOR DYSFUNCTION AND MULTIPLE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN SCLEROSIS THE MESENCEPHALON OCULAR MOTOR MANIFESTATIONS OF SOME METABOLIC Sites and Manifestations of Lesions DISORDERS Neurologic Disorders that Primarily Affect the Mesencephalon EFFECTS OF DRUGS ON EYE MOVEMENTS In this chapter, we survey clinicopathologic correlations proach, although we also discuss certain metabolic, infec- for supranuclear ocular motor disorders. The presentation tious, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases in which su- follows the schema of the 1999 text by Leigh and Zee (1), pranuclear and internuclear disorders of eye movements are and the material in this chapter is intended to complement prominent. -

Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis

Vestibular Neuritis and DISORDERS Labyrinthitis: Infections of the Inner Ear By Charlotte L. Shupert, PhD with contributions from Bridget Kulick, PT and the Vestibular Disorders Association INFECTIONS Result in damage to inner ear and/or nerve. ARTICLE 079 DID THIS ARTICLE HELP YOU? SUPPORT VEDA @ VESTIBULAR.ORG Vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis are disorders resulting from an 5018 NE 15th Ave. infection that inflames the inner ear or the nerves connecting the inner Portland, OR 97211 ear to the brain. This inflammation disrupts the transmission of sensory 1-800-837-8428 information from the ear to the brain. Vertigo, dizziness, and difficulties [email protected] with balance, vision, or hearing may result. vestibular.org Infections of the inner ear are usually viral; less commonly, the cause is bacterial. Such inner ear infections are not the same as middle ear infections, which are the type of bacterial infections common in childhood affecting the area around the eardrum. VESTIBULAR.ORG :: 079 / DISORDERS 1 INNER EAR STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION The inner ear consists of a system of fluid-filled DEFINITIONS tubes and sacs called the labyrinth. The labyrinth serves two functions: hearing and balance. Neuritis Inflamation of the nerve. The hearing function involves the cochlea, a snail- shaped tube filled with fluid and sensitive nerve Labyrinthitis Inflamation of the labyrinth. endings that transmit sound signals to the brain. Bacterial infection where The balance function involves the vestibular bacteria infect the middle organs. Fluid and hair cells in the three loop-shaped ear or the bone surrounding semicircular canals and the sac-shaped utricle and Serous the inner ear produce toxins saccule provide the brain with information about Labyrinthitis that invade the inner ear via head movement. -

Vestibular Neuritis, Labyrinthitis, and a Few Comments Regarding Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss Marcello Cherchi

Vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, and a few comments regarding sudden sensorineural hearing loss Marcello Cherchi §1: What are these diseases, how are they related, and what is their cause? §1.1: What is vestibular neuritis? Vestibular neuritis, also called vestibular neuronitis, was originally described by Margaret Ruth Dix and Charles Skinner Hallpike in 1952 (Dix and Hallpike 1952). It is currently suspected to be an inflammatory-mediated insult (damage) to the balance-related nerve (vestibular nerve) between the ear and the brain that manifests with abrupt-onset, severe dizziness that lasts days to weeks, and occasionally recurs. Although vestibular neuritis is usually regarded as a process affecting the vestibular nerve itself, damage restricted to the vestibule (balance components of the inner ear) would manifest clinically in a similar way, and might be termed “vestibulitis,” although that term is seldom applied (Izraeli, Rachmel et al. 1989). Thus, distinguishing between “vestibular neuritis” (inflammation of the vestibular nerve) and “vestibulitis” (inflammation of the balance-related components of the inner ear) would be difficult. §1.2: What is labyrinthitis? Labyrinthitis is currently suspected to be due to an inflammatory-mediated insult (damage) to both the “hearing component” (the cochlea) and the “balance component” (the semicircular canals and otolith organs) of the inner ear (labyrinth) itself. Labyrinthitis is sometimes also termed “vertigo with sudden hearing loss” (Pogson, Taylor et al. 2016, Kim, Choi et al. 2018) – and we will discuss sudden hearing loss further in a moment. Labyrinthitis usually manifests with severe dizziness (similar to vestibular neuritis) accompanied by ear symptoms on one side (typically hearing loss and tinnitus). -

Hearing Loss, Vertigo and Tinnitus

HEARING LOSS, VERTIGO AND TINNITUS Jonathan Lara, DO April 29, 2012 Hearing Loss Facts S Men are more likely to experience hearing loss than women. S Approximately 17 percent (36 million) of American adults report some degree of hearing loss. S About 2 to 3 out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born deaf or hard-of-hearing. S Nine out of every 10 children who are born deaf are born to parents who can hear. Hearing Loss Facts S The NIDCD estimates that approximately 15 percent (26 million) of Americans between the ages of 20 and 69 have high frequency hearing loss due to exposure to loud sounds or noise at work or in leisure activities. S Only 1 out of 5 people who could benefit from a hearing aid actually wears one. S Three out of 4 children experience ear infection (otitis media) by the time they are 3 years old. Hearing Loss Facts S There is a strong relationship between age and reported hearing loss: 18 percent of American adults 45-64 years old, 30 percent of adults 65-74 years old, and 47 percent of adults 75 years old or older have a hearing impairment. S Roughly 25 million Americans have experienced tinnitus. S Approximately 4,000 new cases of sudden deafness occur each year in the United States. Hearing Loss Facts S Approximately 615,000 individuals have been diagnosed with Ménière's disease in the United States. Another 45,500 are newly diagnosed each year. S One out of every 100,000 individuals per year develops an acoustic neurinoma (vestibular schwannoma). -

Eye Movement Disorders and Neurological Symptoms in Late-Onset Inborn Errors of Metabolism Koens, Lisette H.; Tijssen, Marina A

University of Groningen Eye movement disorders and neurological symptoms in late-onset inborn errors of metabolism Koens, Lisette H.; Tijssen, Marina A. J.; Lange, Fiete; Wolffenbuttel, Bruce H. R.; Rufa, Alessandra; Zee, David S.; de Koning, Tom J. Published in: Movement Disorders DOI: 10.1002/mds.27484 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Koens, L. H., Tijssen, M. A. J., Lange, F., Wolffenbuttel, B. H. R., Rufa, A., Zee, D. S., & de Koning, T. J. (2018). Eye movement disorders and neurological symptoms in late-onset inborn errors of metabolism. Movement Disorders, 33(12), 1844-1856. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.27484 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

Patient Information Patient Information Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) BPPV causes spinning dizziness (‘vertigo’) due to crystals in the inner ear breaking loose. The crystals are normally embedded in a jelly and when we move forwards and backwards, or up and down, in space they send our brain messages about where we are. If they become loose they can find their way into the wrong area and cause the sensation that we are moving when we are actually not – the result is a sudden feeling of spinning, usually set off by turning your head. What causes BPPV? Perhaps half of all cases of BPPV are "idiopathic" – they occur for no known reason. The most common identified cause of BPPV in people under fifty is a previous head injury. In older people the most common cause is ‘wear and tear’ of the vestibular (balance) system of the inner ear. Some people have a history of previous inner ear inflammation with a period of severe, prolonged dizziness. Diagnosing BPPV The diagnosis is made based on history, physical examination and sometimes with hearing or balance testing. Other diagnostic tests may be required: for example, a CT or MRI may be required for cases that don't fit the usual pattern. It is possible to have BPPV in both ears, which may make the diagnosis and treatment more challenging. How is BPPV Treated? BPPV is often described as ‘self-limiting’ because symptoms often subside or disappear without any medical treatment. Symptoms tend to wax and wane. Physical manoeuvres and exercises are very effective in stopping your symptoms, and are the main basis of treatment. -

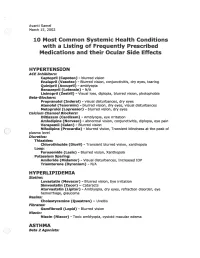

2002 Samel 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with A

Avanti Samel / March 15, 2002 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with a Listing of Frequently Prescribed Medications and their Ocular Side Effects HYPERTENSION ACE Inhibitors: Captopril (Capoten}- blurred vision Enalapril (Vasotec) - Blurred vision, conjunctivitis, dry eyes, tearing Quinipril (Accupril)- amblyopia Benazepril (Lotensin)- N/A Lisinopril (Zestril) - Visual loss, diplopia, blurred vision, photophobia Beta-Blockers: Propranolol (Inderal)- visual disturbances, dry eyes Atenolol (Tenormin)- blurred vision, dry eyes, visual disturbances Metoprolol (Lopressor) - blurred vision, dry eyes calcium Channel Blockers: Diltiazem (Cardizem)- Amblyopia, eye irritation Amlodipine (Norvasc)- abnormal vision, conjunctivitis, diplopia, eye pain Verapamil (Calan)- Blurred vision Nifedipine (Procardia) - blurred vision, Transient blindness at the peak of plasma level · Diuretics: Thiazides: Chlorothiazide (Diuril) - Transient blurred vision, xanthopsia Loop: Furosemide (Lasix) - Blurred vision, Xanthopsia Potassium Sparing: Amiloride (Midamor) - Visual disturbances, Increased lOP Triamterene (Dyrenium)- N/A HYPERLIPIDEMIA Statins: Lovastatin (Mevacor) - Blurred vision, Eye irritation Simvastatin (Zocor)- Cataracts Atorvastatin (Lipitor)- Amblyopia, dry eyes, refraction disorder, eye hemorrhage, glaucoma Resins: Cholestyramine (Questran)- Uveitis Fibrates: Gemfibrozil (Lopid)- Blurred vision Niacin: Niacin (Niacor) - Toxic amblyopia, cystoid macular edema ASTHMA ( ) Beta 2 Agonists: Albuterol (Proventil) - N/A ( Salmeterol (Serevent)- -

Neuro-Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Paraneoplastic Syndromes

STATE OF THE ART Neuro-Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Paraneoplastic Syndromes Melissa W. Ko, MD, Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, and Steven L. Galetta, MD Abstract: Paraneoplastic syndromes with neuro- PARANEOPLASTIC CEREBELLAR ophthalmologic manifestations may involve the cen DEGENERATION tral nervous system, cranial nerves, neuromuscular Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) is junction, optic nerve, uvea, or retina. Most of these a syndrome of subacute severe pancerebellar dysfunction disorders are related to immunologic mechanisms (Table 1). Initially, patients present with gait instability. presumably triggered by the neoplastic expression of Over several days to weeks, they develop truncal and limb neuronal proteins. Accurate recognition is essential to ataxia, dysarthria, and dysphagia. The cerebellar disease appropriate management. eventually stabilizes but leaves patients incapacitated. PCD is most commonly associated with cancers of (/Neuro-Ophthalmol 2008;28:58-68) the lung, ovary, and breast and with Hodgkin disease (7). Ocular motor manifestations include nystagmus, ocular dysmetria, saccadic pursuit, saccadic intrusions and he term "paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome" (PNS) oscillations, and skew deviation (8). Over the last 30 refers to dysfunction of the nervous system caused by T years, at least nine anti-neuronal antibodies have been a benign or malignant tumor via mechanisms other than associated with PCD. However, only about 50% of patients metastasis, coagulopathy, infection, or treatment side with suspected PCD test positive for anti-neuronal anti effects (1). Whereas reports of possible paraneoplastic bodies in serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (9). Anti-Yo neuropathies extend back to the 19th century, cerebellar syndromes associated with cancer were first described by and anti-Tr are the autoantibodies most commonly Brouwerin 1919 (2).