Mcknight 1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

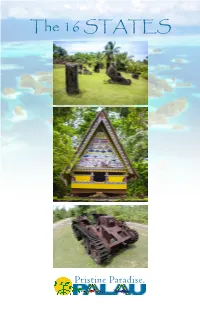

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Palau Protected Areas Network Sustainable Finance Mechanism

Palau Protected Areas Network Sustainable Finance Mechanism Presentation courtesy of the Palau PAN Coordinator’s Office Timeline • 2003 – Leg. Mandate for PAN Act • 2008 – Leg. Mandate for PAN Fund • 2010 – PAN Fund Incorporation • 2010 – Leg. Mandate for Green Fee • 2011 – Board of Directors • 2012 – PAN Fund Office ~ July 2012: PAN Fund Operational Sustainable Funding GREEN FEE ENDOWMENT FUND Departure Fee Micronesia Conservation $15/non-Palauan passport Trust holders 2:1 Matching Quarterly turnover to PAN Goal: Initially $10 Million Fund Green Fee Collection Protected Areas Network Fund Mission: To efficiently and equitably provide funding to the Protected Areas Network and it’s associated activities, through strategic actions and medium-to- long term financial support that will advance effective management and conservation of Palau’s natural and cultural resources. PAN Fund Process MC Endowment Fund Other Sources Investment Earnings Green Fees (Grants, etc.) Protected Area Network Fund PAN Sites PAN System PAN Projects FY 2010 & 2011 – GREEN FEE RPPL - APPROPRIATIONS [FY 2010 & 2011] $ 1,957,967.66 RPPL 8-18 - Disb. from FY 2010 Revenue $ 282,147.41 Sect. 18(C)(1) PAN Office (5%*$1,142,948.10) $ 57,147.41 Sect. 19(e)(A) (1-4) Ngerchelong State Gov't $ 50,000.00 Ngiwal State Gov't $ 50,000.00 Melekeok State Gov't $ 50,000.00 Hatohobei State Gov't $ 50,000.00 Sect. 19(e)(B) Belau National Museum $ 25,000.00 RPPL 8-29 - Disb. From 2010 Revenue $ 20,000.00 Sect. 13(C ) Bureau of Rev., Customs, & Tax $ 20,000.00 RPPL 8-31 - Disb. -

Final Report on the Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply in the Republic of Palau Summary

Palau Public Utilities Corporation No. The Republic of Palau FINAL REPORT ON THE MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR THE UPGRADING OF ELECTRIC POWER SUPPLY IN THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU SUMMARY JULY 2008 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. THE CHUGOKU ELECTRIC POWER CO., INC. IL JR 08-018 PREFACE In response to a request from the Republic of Palau, the Government of Japan decided to conduct the Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply and entrusted to the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team headed by Mr. Mitsuhisa Nishikawa of Yachiyo Engineering Co., LTD. (yec) and consists of yec and Chugoku Electric Power Co., INC. three times between January and June, 2008. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Palau and conducted field surveys at the study area. Upon returning to Japan, the team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of this project and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of Palau for their close cooperation extended to the study. July 2008 Seiichi Nagatsuka Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency Mr. Seiichi Nagatsuka Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL July 2008 Dear Sir, It is my great pleasure to submit herewith the Final Report of “The Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply in the Republic of Palau”. -

Palauan Children Under Japanese Rule: Their Oral Histories Maki Mita

SER 87 Senri Ethnological Reports Senri Ethnological 87 Reports 87 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Palauan Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Their Oral Histories Thier Oral Histories Maki Mita Maki Mita National Museum of Ethnology 2009 Osaka ISSN 1340-6787 ISBN 978-4-901906-72-2 C3039 Senri Ethnological Reports Senri Ethnological Reports is an occasional series published by the National Museum of Ethnology. The volumes present in-depth anthropological, ethnological and related studies written by the Museum staff, research associates, and visiting scholars. General editor Ken’ichi Sudo Associate editors Katsumi Tamura Yuki Konagaya Tetsuo Nishio Nobuhiro Kishigami Akiko Mori Shigeki Kobayashi For information about previous issues see back page and the museum website: http://www.minpaku.ac.jp/publication/ser/ For enquiries about the series, please contact: Publications Unit, National Museum of Ethnology Senri Expo Park, Suita, Osaka, 565-8511 Japan Fax: +81-6-6878-8429. Email: [email protected] Free copies may be requested for educational and research purposes. Haines Transnational Migration: Some Comparative Considerations Senri Ethnological Reports 287 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Their Oral Histories Maki Mita National Museum of Ethnology 2009 Osaka 1 Published by the National Museum of Ethnology Senri Expo Park, Suita, Osaka, 565-8511, Japan ©2009 National Museum of Ethnology, Japan All rights reserved. Printed in Japan by Nakanishi Printing Co., Ltd. Publication Data Senri Ethnological Reports 87 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule: Their Oral Histories Maki Mita. P. 274 Includes bibliographical references and Index. ISSN 1340-6787 ISBN 978-4-901906-72-2 C3039 1. Oral history 2. -

INSECTS of MICRONESIA Homoptera: Fulgoroidea, Supplement

INSECTS OF MICRONESIA Homoptera: Fulgoroidea, Supplement By R.G. FENNAH COMMONWEALTH INSTITUTE OF ENTOMOLOGY, BRITISH MUSEUM (NAT. RIST.), LONDON. This report deals with fulgoroid Homoptera collected in the course of a survey of the insects of Micronesia carried out principally under the auspices of the Pacific Science Board, and is supplementary to my paper published in 1956 (Ins. Micronesia 6(3): 38-211). Collections available are from the Palau Islands, made by B. McDaniel in 1956, C.W. Sabrosky in 1957, F.A. Bianchi in 1963 and J.A. Tenorio in 1963; from the Yap group, made by R.J. Goss in 1950, ].W. Beardsley in 1954 and Sabrosky in 1957; from the southern Mariana Islands, made by G.E. Bohart and ].L. Gressitt in 1945, C.E. Pemberton in 1947, C.]. Davis in 1955, C.F. Clagg in 1956 and N.L.H. Krauss in 1958; from the Bonin Is., made by Clagg in 1956, and F.M. Snyder and W. Mitchell in 1958; from the smaller Caroline atolls, made by W.A. Niering in 1954, by Beardsley in 1954 and McDaniel in 1956; from Ponape, made by S. Uchiyama in 1927; from Wake Island and the Marshall Islands, made by L.D. Tuthill in 1956, Krauss in 1956, Gressitt in 1958, Y. Oshiro in 1959, F.R. Fosberg in 1960 and B.D. Perkins in 1964; and from the Gilbert Islands, made by Krauss in 1957 and Perkins in 1964. Field research was aided by a contract between the Office ofNaval Research, Department of the Navy and the National Academy of Sciences, NR 160 175. -

Palau Crop Production & Food Security Project

Palau Crop Production & Food Security Project Pacific Adaptation to Climate Change (PACC) REPORTING ON STATUS Workshop in Apia, Samoa May 10 –May 14, 2010 Overview of Palau Island: Palau is comprised of 16 states from Kayangel to the north, and Ngerchelong, Ngaraard, Ngiwal, Melekeok, Ngchesar, Airai, Aimeliik, Ngatpang, Ngeremlengui, and Ngardmau located on the big island of Babeldaob to Koror across the bridge to the south and Peleliu and Angaur farther south through the rock islands and Sonsorol and Hatohobei about a days boat ride far south. Ngatpang State was chosen as the PACC’s pilot project in Palau Pilot project in… due to its coastal area fringed with mangroves land uses Ngatpang State! including residential, subsistence agriculture and some small‐ scale commercial agriculture and mari‐culture. The state land area is approximately 9,700 Ngaremlengui State acres in size with the largest “Ngermeduu” bay in the Republic of Palau. Ngermeduu Bay NGATPANG STATE Aimeliik State Portions of the land surrounding the bay have been designated as Ngeremeduu conservation area and are co‐managed by the states of Aimeliik, Ngatpang and Ngaremlengui. There are a total of 389 acres of wetland habitat in Ngatpang, occurring Ngatpang State! for the most part along the low‐lying areas in addition to a total of 1,190 acres of mangrove forests ringing bay. The state has proposed a development of an aqua culture facility in the degraded area. Both wetlands and mangroves are considered an island‐wide resource, warranting coordinated management planning among the states. Ngatpang has a rich and diverse marine resources due to the bay and the associated outer and inner reefs. -

Bureau of Arts and Culture Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs 2013 Traditional Place Names of Palau: from the Shore to the Reef ______

TRADITIONAL PLACE NAMES OF PALAU: FROM THE SHORE TO THE REEF Bureau of Arts and Culture Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs 2013 Traditional Place Names of Palau: From the Shore to the Reef ____________________________ Ngklel a Beluu er a Belau er a Rechuodel: Ngar er a Kebokeb el mo er a Chelemoll by The Palau Society of Historians (Klobak er a Ibetel a Cherechar) and Bureau of Arts and Culture Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs Koror, Republic of Palau 96940 Traditional Customary Practices Palau Series 18-b 2013 THE SOCIETY OF HISTORIANS (KLOBAK ER A IBETEL A CHERECHAR) DUI\ NGAKL (Historian) BELUU (State) 1. Diraii Yosko Ngiratumerang Aimeliik 2. Uchelrutchei Wataru Elbelau Ngaremlengui 3. Ochob Rachel Becheserrak Koror 4. Floriano Felix Ngaraard 5. Iechadrairikl Renguul Kloulechad Ngarchelong 6. Ngirachebicheb August Ngirameketii Ngiwal 7. Rechiuang Demei Otobed Ngatpang 8. Ngirkebai Aichi Kumangai Ngardmau 9. Dirachesuroi Theodosia F. Blailes Angaur 10. Rebechall Takeo Ngirmekur Airai 11. Rechedebechei Ananias Bultedaob Ngchesar 12. Renguul Peter Elechuus Melekeok State 13. Smau Amalei Ngirngesang Peleliu 14. Obakrakelau Ngiraked Bandary Kayangel 15. Orue-Tamor Albis Sonsorol 16. Domiciano Andrew Hatohobei Bureau of Arts and Culture, Koror, Republic of Palau 96940 ©2013 by the Bureau of Arts and Culture All rights reserved. Published 2013. Palau Society of Historians Traditional Place Names of Palau: From the Shore to the Reef (Ngklel a Beluu er a Belau er a Rechuodel: Ngar er a Kebokeb el mo er a Chelemoll) Palauan Series 18-b ANTHROPOLOGY RESEARCH SERIES Volume 1 Rechuodel 1: Traditional Culture and Lifeways Long Ago in Palau by the Palau Society of Historians, English Translation by DeVerne Reed Smith. -

Palau National 2013 Report

Republic May 27 of Palau National 2013 Report The Republic of Palau has met or nearly accomplished most of the 2015 Millennium Development Goals. As a leader in sustainable development and conservation, Palau is committed to work towards universal and affordable education and health; clean water, air and sea; ample supply of Third drinking water and local foods within healthy ecosystems. There is a rising concern for the impacts of Climate Change to the well being of the International community. Homes, food and marine ecosystems were lost during Conference on Typhoon Bopha. There is concern for increasing GHG emissions and Palau acknowledges the need to mitigate GHG emission with clean energy Small Island options for infrastructure and transport. Non- communicable diseases are a major concern and a concerted effort is being made to combat NCDs Developing through healthy diet and exercise. Palau is working towards a shared States vision in its planning and budgeting process and invites the global community to support priorities sent form by the nation to meet the challenges of tomorrow. Draft National Report May 27, 2013 The Environment, Inc. Contents I. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................4 II. Synthesis of preparations undertaken in the country: National overview ................................................5 III National assessment of the progress to date and the remaining gaps in the implementation of the MDGs, -

7. INTERVIEWS with PALAUANS (Ngiwal, Airai, Rdialul, Ngaraard) Multiple Dates: Many Other American Aircraft Lost Over Palau Have

7. INTERVIEWS WITH PALAUANS (Ngiwal, Airai, Rdialul, Ngaraard) Multiple Dates : Many other American aircraft lost over Palau have never been found. Accordingly, the P-MAN XI team continued to request and conduct videoed interviews (with permission obtained prior to the interview using the new form developed with the Palauan Bureau of Arts and Crafts) with Palauans to seek information leading to additional crash sites, MIAs or POWs. Because of the shorter three week mission, the team only was able to conduct 7 interviews with Palauan elders, historians and hunters throughout Palau, which follow. The consent form used is at the end of this section. This section was assembled by Molly Osborne, with great appreciation, and edited by me. a. Interview #1 : 20MAR09 with Vince Blaiyok (born 1953), Director of Tourism & Culture- Airai. © K. Rasdorf, 2009 This is a follow- up interview from last year’s mission. Reid (not present this year) and Pat wanted to ask more questions about sightings of one or more aircraft in Airai. Vince had family present during WWII where they stayed in caves in the Ngeream area/mangroves (noted on annotated map below). NON-CONFIDENTIAL: FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Page 85 Aircraft 1: “Painted Lady” airplane (the report from last year: blue, single -engine aircraft lying in 35 feet of water in a channel south of Airai): Mr. Blaiyok had not see this but his elders who have now passed on said they did. (NOTE: IN ~1994, Surangel Whipps reported to Pat of knowing people who saw this aircraft; dives in the channel, which can have swift currents and very low visibility, in 1994 and 1996 failed to find any such aircraft or related debris). -

The Whispered Memories of Belau's Bais

The Whispered Memories of Belau’s Bais A cherechar a lokelii A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES DECEMBER 2014 BY: Kora Mechelins Iechad THESIS COMMITTEE: Dr. Alice Te Punga Somerville, Chairperson Dr. Terence Wesley-Smith Dr. Tarcisius Kabutaulaka i © 2014 Kora Mechelins Iechad ii We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Pacific Islands Studies. __________________________________ Dr. Alice Te Punga Somerville Chairperson __________________________________ Dr. Terence Wesley-Smith __________________________________ Dr. Tarcisius Kabutaulaka iii Acknowledgements I want to take this opportunity to give thanks to all the people who help me throughout this phase of my educational journey. Without your words of wisdom and guidance, none of this would be a reality. To my family: you are the reason I have been able to take this journey. Your push and love has continuously motivated to reach for the stars. Grandma Julie and Pappy Reg: thank you for your love, buying my books, filling my icebox and tet every time you visit, and not questioning why I chose to get a Master’s in Pacific Islands Studies. Your belief that I will make the best decisions push me to work harder and be a better person. To my uncle Johnson Iechad: thank you for funding my research and being my biggest advocate. Without our endless talks about ideas for this thesis and words of encouragement I wouldn’t of come this far. -

Ngardmau OSCA Protected Areas Management Plan 2018-2023

Ongedechuul System of Conservation Areas Protected Areas Management Plan 2018 – 2023 NGARDMAU, PALAU Ngardmau Community Planning Teams 2017 Orrukem Sakaziro·Masae I. Isaac·Tkelkang Aderkeroi·Beouch Demei Obakrairur·Joshua Bukringang·Bradley Kumangai·Tiare T. Holm·Gibbons Masahiro 2011 Victor R. Masahiro·Alson Ngiraiwet·Bradley Kumangai·Elizabeth Ngirmekur·Tiare T. Holm Ongedechuul System of Conservation Areas (OSCA), Ngardmau Protected Areas Management Plan 2018 – 2023 Developed by the Ngardmau Community Planning Team with OSCA Board and Staff Assistance provided by Palau Conservation Society Funded by an MCT Grant Award Acknowledgement With this second iteration of protected areas management planning process for the Ongedechuul System of Conservation Areas (OSCA), the Ngardmau Conservation Board and Community Representatives who together worked to develop this updated Ongedechuul System of Conservation Areas Management Plan, 2018 – 2023 extends its appreciation and recognize the staff of the OSCA Management Office, who were eager and enthusiastic, we hope the process was engaging and a great learning experience for each and everyone of you. Thank you for your support. Most importantly, our sincere appreciation- we express to Governor Johnston B. Ilengelekei, Speaker Sabo Esebei and members of the 9th el Kelulul Ngardmau, Beouch Demei Obakrairur and the Rubekul Ngardmau for giving us your trust and confidence to plan for the protection, conservation, and sustainable uses of our rich natural resources. We have done our best to accurately depict the wishes of our community, and conveyed them in a manner we hope are deemed practical to act on over the next five years. We believe, by staying within the course laid out in the Plan we will be able to achieve our desired outcome, and gain real and sustainable benefits from OSCA as a community. -

Statistical Yearbook Republic of Palau

2012 Statistical Yearbook Republic of Palau Bureau of Budget & Planning Ministry of Finance ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The 2012 Statistical Yearbook publication was made possible through the support of many government agencies as well as some enterprises in the private sector. The information con- tained in this publication will provide the baseline data required and other information benefi- cial to the government and private sectors. The statistical yearbook is an annual publication of demographic, economic, social and housing characteristics. It serves as a summary of aggregated statistics about the Republic of Palau, and a reference for planners and many other groups of people for planning and implementing acitivities concerned with the development of our nation. We acknowledge the effort of the government agencies and other individuals in making this publication possible. We commend the staff of the Office of Planning and Statistics for their continued effort in the compilation of this publication. INTRODUCTION The Republic of Palau became an Independent Nation on October 1, 1994 with the implemen- tation of the Compact of Free Association between Palau and the United States of America. Palau stretches from about 2 to 8 degrees north latitude and 131 to 135 degrees east longitude. Palau covers 189 square miles of land area including the rock islands. The surrounding sea area in- cludes an exclusive economic zone extending over 237,850 square miles. The capital of Palau was relocated to Ngerulmud, Melekeok in 2006. Koror remain the economic center for Palau, with a land area of 7.1 square miles where two thirds of the population resides. Koror lies just south of Micronesia’s second largest island, Babeldaob which contains 153 square miles of un- dulating forests, grasslands, rivers, waterfalls, wetlands, mangroves and some of the most beau- tiful stretches of beaches.