Ngardmau OSCA Protected Areas Management Plan 2018-2023

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

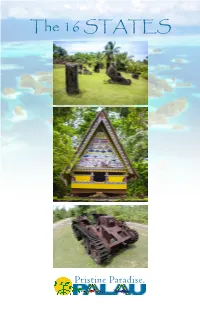

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Palau Protected Areas Network Sustainable Finance Mechanism

Palau Protected Areas Network Sustainable Finance Mechanism Presentation courtesy of the Palau PAN Coordinator’s Office Timeline • 2003 – Leg. Mandate for PAN Act • 2008 – Leg. Mandate for PAN Fund • 2010 – PAN Fund Incorporation • 2010 – Leg. Mandate for Green Fee • 2011 – Board of Directors • 2012 – PAN Fund Office ~ July 2012: PAN Fund Operational Sustainable Funding GREEN FEE ENDOWMENT FUND Departure Fee Micronesia Conservation $15/non-Palauan passport Trust holders 2:1 Matching Quarterly turnover to PAN Goal: Initially $10 Million Fund Green Fee Collection Protected Areas Network Fund Mission: To efficiently and equitably provide funding to the Protected Areas Network and it’s associated activities, through strategic actions and medium-to- long term financial support that will advance effective management and conservation of Palau’s natural and cultural resources. PAN Fund Process MC Endowment Fund Other Sources Investment Earnings Green Fees (Grants, etc.) Protected Area Network Fund PAN Sites PAN System PAN Projects FY 2010 & 2011 – GREEN FEE RPPL - APPROPRIATIONS [FY 2010 & 2011] $ 1,957,967.66 RPPL 8-18 - Disb. from FY 2010 Revenue $ 282,147.41 Sect. 18(C)(1) PAN Office (5%*$1,142,948.10) $ 57,147.41 Sect. 19(e)(A) (1-4) Ngerchelong State Gov't $ 50,000.00 Ngiwal State Gov't $ 50,000.00 Melekeok State Gov't $ 50,000.00 Hatohobei State Gov't $ 50,000.00 Sect. 19(e)(B) Belau National Museum $ 25,000.00 RPPL 8-29 - Disb. From 2010 Revenue $ 20,000.00 Sect. 13(C ) Bureau of Rev., Customs, & Tax $ 20,000.00 RPPL 8-31 - Disb. -

Final Report on the Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply in the Republic of Palau Summary

Palau Public Utilities Corporation No. The Republic of Palau FINAL REPORT ON THE MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR THE UPGRADING OF ELECTRIC POWER SUPPLY IN THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU SUMMARY JULY 2008 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. THE CHUGOKU ELECTRIC POWER CO., INC. IL JR 08-018 PREFACE In response to a request from the Republic of Palau, the Government of Japan decided to conduct the Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply and entrusted to the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team headed by Mr. Mitsuhisa Nishikawa of Yachiyo Engineering Co., LTD. (yec) and consists of yec and Chugoku Electric Power Co., INC. three times between January and June, 2008. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Palau and conducted field surveys at the study area. Upon returning to Japan, the team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of this project and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of Palau for their close cooperation extended to the study. July 2008 Seiichi Nagatsuka Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency Mr. Seiichi Nagatsuka Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL July 2008 Dear Sir, It is my great pleasure to submit herewith the Final Report of “The Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply in the Republic of Palau”. -

2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU APPELLATE DIVISION NGEREMLENGUI STATE GOVERNMENT and NGEREMLENGUI STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellants/Cross-Appellees, v. NGARDMAU STATE GOVERNMENT and NGARDMAU STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellees/Cross-Appellants. Cite as: 2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No. 15-014 Appeal from Civil Action No. 13-020 Decided: November 16, 2016 Counsel for Ngeremlengui ............................................... Oldiais Ngiraikelau Counsel for Ngardmau ..................................................... Yukiwo P. Dengokl Matthew S. Kane BEFORE: KATHLEEN M. SALII, Associate Justice LOURDES F. MATERNE, Associate Justice C. QUAY POLLOI, Associate Justice Pro Tem Appeal from the Trial Division, the Honorable R. Ashby Pate, Associate Justice, presiding. OPINION PER CURIAM: [¶ 1] This appeal arises from a dispute between the neighboring States of Ngeremlengui and Ngardmau regarding their common boundary line. In 2013, the Ngeremlengui State Government and Ngeremlengui State Public Lands Authority (Ngeremlengui) filed a civil suit against the Ngardmau State Government and Ngardmau State Public Lands Authority (Ngardmau), seeking a judgment declaring the legal boundary line between the two states. After extensive evidentiary proceedings and a trial, the Trial Division issued a decision adjudging that common boundary line. [¶ 2] Each state has appealed a portion of that decision and judgment. Ngardmau argues that the Trial Division applied an incorrect legal standard to determine the boundary line. Ngardmau also argues that the Trial Division Ngeremlengui v. Ngardmau, 2016 Palau 24 clearly erred in making factual determinations concerning parts of the common land boundary. Ngeremlengui argues that the Trial Division clearly erred in making factual determinations concerning a part of the common maritime boundary. For the reasons below, the judgment of the Trial Division is AFFIRMED. -

Conservation Areas

Republic of Palau Conservation Areas Palauans have always understood the intricate balance between the health of Palau’s natural habitats and the long-term health of its people. For many centuries, Palauans have practiced conservation and sustainable use of its natural habitats. To date, Palau has 290km² (112 square miles) of natural habitat, both marine and terrestrial, that is under some sort of protection. This is significant considering that Palau has a land mass of approximately 363 square kilometers. The national government, state governments, traditional leaders, NGOs, and the communities as a whole have all played a instrumental role in the creation and management of Palau’s conservation areas. Area Authority Year Approx size Regulations Ngerukewid Islands Wildlife no fishing, hunting, or Preserve (Seventy Islands Republic of Palau 1999 12km2 distrubance of any kind governed according to the reserve board Ngeruangel Reserve Kayangel State 1996 35km2 management plan Ngarchelong & Ngarchelong/Kayangel Reef Kayangel Chiefs - no fishing in 8 channels Channels Traditional bul 1994 90km2 during April through July Ebiil Channel Conservation Area Ngarchelong State 2000 15km2 no entry or fishing only traditional Ngaraard Conservation Area subsistence and (mangrove) Ngaraard State 1994 1.8km2 educational uses allowed Ngardmau Conservation Area (reef flat, Taki Waterfall, no entry, fishing, or Mount Ngerchelchuus) Ngardmau State 1998 7km2 hunting for 5 years Ngemai Conservation Area Ngiwal State 1997 1km2 no entry or fishing Ngerumekaol -

Republic of Palau Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan, 2007-2012

National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007 - 2012 R National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 To all Palauans, who make the Cancer Journey May their suffering return as skills and knowledge So that the people of Palau and all people can be Cancer Free! Special Thanks to The planning groups and their chairs whose energy, Interest and dedication in working together to develop the road map for cancer care in Palau. We also would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Grant # U55-CCU922043) National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 October 15, 2006 Dear Colleagues, This is the National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau. The National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau provides a road map for nation wide cancer prevention and control strategies from 2007 through to 2012. This plan is possible through support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA), the Ministry of Health (Palau) and OMUB (Community Advisory Group, Palau). This plan is a product of collaborative work between the Ministry of Health and the Palauan community in their common effort to create a strategic plan that can guide future activities in preventing and controlling cancers in Palau. The plan was designed to address prevention, early detection, treatment, palliative care strategies and survivorship support activities. The collaboration between the health sector and community ensures a strong commitment to its implementation and evaluation. The Republic of Palau trusts that you will find this publication to be a relevant and useful reference for information or for people seeking assistance in our common effort to reduce the burden of cancer in Palau. -

Palauan Children Under Japanese Rule: Their Oral Histories Maki Mita

SER 87 Senri Ethnological Reports Senri Ethnological 87 Reports 87 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Palauan Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Their Oral Histories Thier Oral Histories Maki Mita Maki Mita National Museum of Ethnology 2009 Osaka ISSN 1340-6787 ISBN 978-4-901906-72-2 C3039 Senri Ethnological Reports Senri Ethnological Reports is an occasional series published by the National Museum of Ethnology. The volumes present in-depth anthropological, ethnological and related studies written by the Museum staff, research associates, and visiting scholars. General editor Ken’ichi Sudo Associate editors Katsumi Tamura Yuki Konagaya Tetsuo Nishio Nobuhiro Kishigami Akiko Mori Shigeki Kobayashi For information about previous issues see back page and the museum website: http://www.minpaku.ac.jp/publication/ser/ For enquiries about the series, please contact: Publications Unit, National Museum of Ethnology Senri Expo Park, Suita, Osaka, 565-8511 Japan Fax: +81-6-6878-8429. Email: [email protected] Free copies may be requested for educational and research purposes. Haines Transnational Migration: Some Comparative Considerations Senri Ethnological Reports 287 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Their Oral Histories Maki Mita National Museum of Ethnology 2009 Osaka 1 Published by the National Museum of Ethnology Senri Expo Park, Suita, Osaka, 565-8511, Japan ©2009 National Museum of Ethnology, Japan All rights reserved. Printed in Japan by Nakanishi Printing Co., Ltd. Publication Data Senri Ethnological Reports 87 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule: Their Oral Histories Maki Mita. P. 274 Includes bibliographical references and Index. ISSN 1340-6787 ISBN 978-4-901906-72-2 C3039 1. Oral history 2. -

INSECTS of MICRONESIA Homoptera: Fulgoroidea, Supplement

INSECTS OF MICRONESIA Homoptera: Fulgoroidea, Supplement By R.G. FENNAH COMMONWEALTH INSTITUTE OF ENTOMOLOGY, BRITISH MUSEUM (NAT. RIST.), LONDON. This report deals with fulgoroid Homoptera collected in the course of a survey of the insects of Micronesia carried out principally under the auspices of the Pacific Science Board, and is supplementary to my paper published in 1956 (Ins. Micronesia 6(3): 38-211). Collections available are from the Palau Islands, made by B. McDaniel in 1956, C.W. Sabrosky in 1957, F.A. Bianchi in 1963 and J.A. Tenorio in 1963; from the Yap group, made by R.J. Goss in 1950, ].W. Beardsley in 1954 and Sabrosky in 1957; from the southern Mariana Islands, made by G.E. Bohart and ].L. Gressitt in 1945, C.E. Pemberton in 1947, C.]. Davis in 1955, C.F. Clagg in 1956 and N.L.H. Krauss in 1958; from the Bonin Is., made by Clagg in 1956, and F.M. Snyder and W. Mitchell in 1958; from the smaller Caroline atolls, made by W.A. Niering in 1954, by Beardsley in 1954 and McDaniel in 1956; from Ponape, made by S. Uchiyama in 1927; from Wake Island and the Marshall Islands, made by L.D. Tuthill in 1956, Krauss in 1956, Gressitt in 1958, Y. Oshiro in 1959, F.R. Fosberg in 1960 and B.D. Perkins in 1964; and from the Gilbert Islands, made by Krauss in 1957 and Perkins in 1964. Field research was aided by a contract between the Office ofNaval Research, Department of the Navy and the National Academy of Sciences, NR 160 175. -

School Calendar 2021-2022 6.27.2020

School Calendar School Year 2021-2022 August 02, 2021 to May 13, 2022 MOE Vision & Mission Statements, Important Dates & Holidays STATE HOLIDAYS MINISTRY OF EDUCATION August 15 Peleliu State Liberation Day August 30 Aimeliik: Alfonso Rebechong Oiterong Day VISION STATEMENT: Cherrengelel a osenged el kirel a skuul. September 11 Peleliu State Constitution Day September 13 Kayangel State Constitution Day September 13 Ngardmau Memorial Day A rengalek er a skuul a mo ungil chad er a Belau me a beluulechad. September 28 Ngchesar State Memorial Day Our students will be successful in the Palauan society and the world. October 01 Ngardmau Constitution Day October 08 Angaur State Liberation Day MISSION STATEMENT: Ngerchelel a skuul er a Belau. October 08 Ngarchelong State Constitution Day October 21 Koror State Constitution Day November 05 Ngarchelong State Memorial Day A skuul er a Belau, kaukledem ngii me a rengalek er a skuul, rechedam me November 02 Angaur State Memorial Day a rechedil me a buai, a mo kudmeklii a ungil el klechad er a rengalek er a November 04 Melekeok State Constitution Day skuul el okiu a ulterekokl el suobel me a ungil osisechakl el ngar er a ungil November 17 Angaur: President Lazarus Salii Memorial Day el olsechelel a omesuub. November 25 Melekeok State Memorial Day November 27 Peleliu State Memorial Day January 06 Ngeremlengui State Constitution Day The Republic of Palau Ministry of Education, in partnership with students, January 12 Ngaraard State Constitution Day parents, and the community, is to ensure student success through effective January 23 Sonsorol State Constitution Day curriculum and instruction in a conducive learning environment. -

2014-2019 Palau National Review of Implementation of the Beijing Declaration -25Th Anniversary of the 4Th World Conference on Women

2014-2019 Palau National Review of Implementation of the Beijing Declaration -25th Anniversary of the 4th World Conference on Women Republic of Palau National Review for the Implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995) and the outcomes of the twenty-third special session of the General Assembly (2000) in the context of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women and the adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action 2020 April 2019 Submitted by Minister Baklai Temengil-Chilton Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs REPUBLIC OF PALAU Tel: (680) 767 1126 Fax: (680) 767 -3354 Compiled by Ann Hillmann Kitalong, PhD The Environment, Inc. 1 2014-2019 Palau National Review of Implementation of the Beijing Declaration -25th Anniversary of the 4th World Conference on Women Acknowledgements Many people contributed to the oversight, research, information, and writing of this review. We acknowledge Bilung Gloria G. Salii and Ebilreklai Gracia Yalap, the two highest ranking traditional women leaders responsible for the Mechesil Belau Annual Conference, that celebrated its 25th Anniversary in 2018. We especially thank Bilung Gloria G. Salii for giving the opening remarks for the validation workshop. We acknowledge the government of the Republic of Palau for undergoing the review, and for the open and constructive participation of so many participants. We wish to acknowledge the members of civil society and donor and development partners who participated in interviews and focus group discussion for their valuable insights. The primary government focal points were the Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs (MCCA), Minister Baklai Temengil-Chilon; Director of Aging and Gender, Ms. -

Palau Crop Production & Food Security Project

Palau Crop Production & Food Security Project Pacific Adaptation to Climate Change (PACC) REPORTING ON STATUS Workshop in Apia, Samoa May 10 –May 14, 2010 Overview of Palau Island: Palau is comprised of 16 states from Kayangel to the north, and Ngerchelong, Ngaraard, Ngiwal, Melekeok, Ngchesar, Airai, Aimeliik, Ngatpang, Ngeremlengui, and Ngardmau located on the big island of Babeldaob to Koror across the bridge to the south and Peleliu and Angaur farther south through the rock islands and Sonsorol and Hatohobei about a days boat ride far south. Ngatpang State was chosen as the PACC’s pilot project in Palau Pilot project in… due to its coastal area fringed with mangroves land uses Ngatpang State! including residential, subsistence agriculture and some small‐ scale commercial agriculture and mari‐culture. The state land area is approximately 9,700 Ngaremlengui State acres in size with the largest “Ngermeduu” bay in the Republic of Palau. Ngermeduu Bay NGATPANG STATE Aimeliik State Portions of the land surrounding the bay have been designated as Ngeremeduu conservation area and are co‐managed by the states of Aimeliik, Ngatpang and Ngaremlengui. There are a total of 389 acres of wetland habitat in Ngatpang, occurring Ngatpang State! for the most part along the low‐lying areas in addition to a total of 1,190 acres of mangrove forests ringing bay. The state has proposed a development of an aqua culture facility in the degraded area. Both wetlands and mangroves are considered an island‐wide resource, warranting coordinated management planning among the states. Ngatpang has a rich and diverse marine resources due to the bay and the associated outer and inner reefs. -

Proposed National Landfill Project

Environmental Impact Statement for The Proposed National Landfill Imul Hamlet, Aimeliik State Alternate Site A at Ongerarekieu, Imul Hamlet Aimeliik in 2009 Proposed National Landfill Alternative Site B at Ngeruchael, Imul Hamlet Aimeliik in 2017 March 2017 Prepared for: Prepared By: Capital Improvement Project The Environment, Inc. Box 1696 Koror, Palau 96940 Koror, Palau 96940 The Environment, Inc. Proposed National Landfill 2/8/18 Draft EIS Alternative Site A Ongerarekieu and Alternate Site B Ngeruchael, Imul Hamlet Aimeliik State 1. Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ 2 2. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 3. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Identification of the Applicant .................................................................................. 6 3.2 Identification of the Environmental Assessment Company that prepared the EA. .. 6 3.3 EA Process Documentation ...................................................................................... 8 3.4 Summary List of assessment methodology used for the land-based and water-based assessment of the project. ............................................................................................... 8 4. Detailed Project Description ....................................................................................