2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NGERKEBAI CLAN, Appellant, V

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU APPELLATE DIVISION NGERKEBAI CLAN, Appellant, v. NGEREMLENGUI STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellee. Cite as: 2018 Palau 16 Civil Appeal No. 17-011 Appeal from LC/B 10-00072 Decided: August 21, 2018 Counsel for Appellant ..................................................... Vameline Singeo Counsel for Appellee …………… ................................ Masami Elbelau, Jr. BEFORE: ARTHUR NGIRAKLSONG, Chief Justice R. BARRIE MICHELSEN, Associate Justice DENNIS K. YAMASE, Associate Justice Appeal from the Land Court, the Honorable Rose Mary Skebong, Senior Judge, presiding. OPINION PER CURIAM: [¶ 1] The case of Ngeremlengui State Government v. Ngardmau State Government, 2016 Palau 24, set the boundary between those two states. The resolution of that case established that Bureau of Lands and Surveys Lot 201 01 H 003-001(“Lot 001”) lies within the State of Ngeremlengui, just as it had been located within Ngeremlengui Municipality in Trust Territory times. [¶ 2] This Land Court appeal brought by Ngerkebai Clan concerns ownership of Lot 001. The Land Court awarded the property to Ngeremlengui State Public Lands Authority. We affirm. Ngerkebai Clan v. Ngeremlengui State Pub. Lands Auth., 2018 Palau 16 [¶ 3] Ngerkebai Clan claimed ownership of Lot 001 based upon a 1963 quitclaim deed it received from the Trust Territory Government. The validity of the deed, and its transfer of land to Ngerkebai Clan, is not disputed. Therefore, the task of the Land Court was to determine whether Lot 001 was within the 1963 conveyance. [¶ 4] The Land Court held that the Trust Territory’s quitclaim deed showed the property’s southwestern boundary at the Ngermasch River, which placed all of the land conveyed within Ngardmau State, and therefore north of Lot 001. -

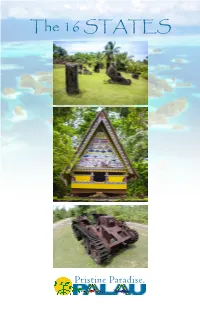

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

PCC CRE Supports Local Aquaculture Farm Fall 2020 Emergency Evacuation Drill

Friday, September 18, 2020 Weekly Newsletter Volume 22, Issue 38 PCC CRE Supports Local Aquaculture Farm Fall 2020 Emergency Evacuation Drill PCC President Dr. Tellei & Dean Sheman Daniel during emer- gency evacuation drill On Monday, September 14, 2020 Palau Inset: Mangrove crablets; Rabbitfish and mangrove crab juveniles deliver to Community College conducted an emergen- ORC farm in Airai cy evacuation drill in accordance with the On September 11, 2020, the PCC-CRE aquaculture staff college Emergency Drill Policy. The emer- delivered a total of 1,000 mangrove crab and 120 rabbit- gency drill or exerise are carried out twice a fish juveniles to the newly established mangrove crab farm year to prepare both staff and students in an of the Oikull Rubak Council (ORC) that is located near anticipated emergency scenario. They are Risao Rechirei’s residence in Airai State. These juveniles designed to provide training, reduce confu- were produced from mangrove crab and rabbitfish seed sion, and verify the adequacy of emergency production projects that are currently being conducted at response activities and equipment. The col- PCC Hatchery in Ngeremlengui State. The ½ inch sized lege Emergency Preparedeness Task Force crablets were temporarily stocked in a stationary net cage (EPTF) is charged with the implementation that was installed in the watered area of the farm. Crablets of emergency drill such as fire, explosions, will be grown that way until they reach the size that could earthquakes that threaten the health and no longer escape through the holes of the mangrove crab well being of staff and students. EPTF not farm’s perimeter screen. -

The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future

OIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIA The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future The Republic of Palau is located roughly 500 miles east of the Philippines in the Western Pacific Ocean. The country consists of 189 square miles of land spread over more than 340 islands, only nine of which are inhabited: 95% of the land area lies within a single reef structure that includes the islands of Babeldaob (a.k.a. Babelthuap), Peleliu and Koror. Palau and the United States have a strong relationship as enshrined in the Compact of Free Association, U.S. Public Law 99-658. Palau has made a concerted effort in goals set forth in its energy policy. recent years to address the technical, The country completed its National policy, social and economic hurdles Climate Change Policy in 2015 and Energy & Climate Facts to deploying energy efficiency and made a commitment to reduce Total capacity (2015): 40.1 MW renewable energy technologies, and has national greenhouse gas emissions Diesel: 38.8 MW taken measures to mitigate and adapt to (GHGs) as part of the United Nations Solar PV: 1.3 MW climate change. This work is grounded in Framework Convention on Climate Total generation (2014): 78,133 MWh Palau’s 2010 National Energy Policy. Change (UNFCCC). Demand for electricity (2015): Palau has also developed an energy action However with a population of just Average/Peak: 8.9/13.5 MW plan to outline concrete steps the island over 21,000 and a gross national GHG emissions per capita: 13.56 tCO₂e nation could take to achieve the energy income per capita of only US$11,110 (2011) in 2014, Palau will need assistance Residential electric rate: $0.28/kWh 7°45|N (2013 average) Arekalong from the international community in REPUBLIC Peninsula order to fully implement its energy Population (2015): 21,265 OF PALAU and climate goals. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) CbfotfZ 3^3 / UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC QNGSLULIJUL AND/OR COMMON same LOCATION STREET& NUMBER Uehuladokoe __NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Melekeok VICINITY OF Babelthuap Island___________ STATE Palau Districtf Trust CODETerritory J of the PacificCOUNTY Islands 96950CODE CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —2JJNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _?SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _RELIGIOUS OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO, —MILITARY XOTHER: storage [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trust Territory Government/in trust tc? Chief Reklai STREET & NUMBER Okemii Saipan Headquarters Palau District CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Municipal Office STREET & NUMBER Ngerams CITY, TOWN STATE Melekeok, Babelthuap Island^ TTPI 96950 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none, DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD X_RUINS _ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED ——————————DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Ongeluluul is a stone platform along the main road te£ Old Melekeok Village to west/southwest further inland about 100 yards from the boathouse along ttef shoreline. The platform is about EO feet by 20 feet separate from the main road by a small creek paralleling the road eastward. -

The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau

THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF INITIAL HUMAN SETTLEMENT IN PALAU, WESTERN MICRONESIA by JESSICA H. STONE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jessica H. Stone Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Anthropology by: Scott M. Fitzpatrick Chairperson Nelson Ting Core Member Dennis H. O’Rourke Core Member Stephen R. Frost Core Member James Watkins Institutional Representative and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020 ii © 2020 Jessica H. Stone iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Jessica H. Stone Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology June 2020 Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia The initial settlement of Remote Oceania represents the world’s last major wave of human dispersal. While transdisciplinary models involving linguistic, archaeological, and biological data have been utilized in the Pacific to develop basic chronologies and trajectories of initial human settlement, a number of elusive gaps remain in our understanding of the region’s colonization history. This is especially true in Micronesia, where a paucity of human skeletal material dating to the earliest periods of settlement have hindered biological contributions to colonization models. The Chelechol ra Orrak site in Palau, western Micronesia, contains the largest and oldest human skeletal assemblage in the region, and is one of only two known sites that represent some of the earliest settlers in the Pacific. -

Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau

THREA TENED ENDEMIC PLANTS OF PALAU BIODI VERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 19: Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Craig Costion, James Cook University, Australia Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Photo credits: Craig Costion (unless cited otherwise) Cover photograph: Parkia flowers. © Craig Costion Series Editors: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, -

Typhoon Surigae

PRCS Situation Report 15 Coverage of Situation Report: 6 PM, May 14 – 6 PM, May 19, 2021 TYPHOON SURIGAE Highlights • Initial Disaster Assessments for all households in Palau in the aftermath of Typhoon Surigae has ended. PRCS and State Governments are currently working together to distribute Non-food items (NFIs) and Cash Voucher Assistance (CVAs) to households affected by Typhoon Surigae. • International Organization for Migration Agency (IOM) Palau Office donated 1,500 tarpaulins and 350 hygiene kits to PRCS as part of relief supplies to be distributed to households affected by typhoon Surigae. • Non-food items (NFIs) for Category 1 damaged households in Melekeok, Ngaraard, Ngatpang, Ngchesar, and Ngeremlengui states have been picked up by their respective state governments. They will distribute to recipients in their states. Photos Above: (Left) NFIs for Category 1 damaged households packed and ready for Melekeok state R-DATs to pick up. (Middle) PRCS staff and volunteer assisting Ngeremlengui state R-DATs in NFIs unto their truck. (Right) PRCS staff going over distribution list with Airai state R-DAT. Photos by L. Afamasaga (left) & M. Rechucher (middle & right). • Babeldaob states with Category 2 damaged households have received Cash Voucher Assistance (CVAs) from PRCS through their own state governments. • A handover of CVAs between Koror and Airai states and PRCS took place at PRCS Conference room. The states also collected NFIs for Category 2 damaged households. The state governments are responsible for handing out CVAs and NFIs to households in their own states. Photo above: PRCS National Governing Board Chairman Santy Asanuma handing out CVAs to Koror State Government Chief of Staff Joleen Ngoriakl. -

Conservation Areas

Republic of Palau Conservation Areas Palauans have always understood the intricate balance between the health of Palau’s natural habitats and the long-term health of its people. For many centuries, Palauans have practiced conservation and sustainable use of its natural habitats. To date, Palau has 290km² (112 square miles) of natural habitat, both marine and terrestrial, that is under some sort of protection. This is significant considering that Palau has a land mass of approximately 363 square kilometers. The national government, state governments, traditional leaders, NGOs, and the communities as a whole have all played a instrumental role in the creation and management of Palau’s conservation areas. Area Authority Year Approx size Regulations Ngerukewid Islands Wildlife no fishing, hunting, or Preserve (Seventy Islands Republic of Palau 1999 12km2 distrubance of any kind governed according to the reserve board Ngeruangel Reserve Kayangel State 1996 35km2 management plan Ngarchelong & Ngarchelong/Kayangel Reef Kayangel Chiefs - no fishing in 8 channels Channels Traditional bul 1994 90km2 during April through July Ebiil Channel Conservation Area Ngarchelong State 2000 15km2 no entry or fishing only traditional Ngaraard Conservation Area subsistence and (mangrove) Ngaraard State 1994 1.8km2 educational uses allowed Ngardmau Conservation Area (reef flat, Taki Waterfall, no entry, fishing, or Mount Ngerchelchuus) Ngardmau State 1998 7km2 hunting for 5 years Ngemai Conservation Area Ngiwal State 1997 1km2 no entry or fishing Ngerumekaol -

Ngchesar State Protected Areas | PAN Site Mesekelat and Ngelukes Conservation Area Ngchesar State Vision Ngelukes Conservation A

Ngchesar State Protected Areas | PAN Site Mesekelat and Ngelukes Conservation Area January 2016 │ Fact Sheet Ngchesar State Ngchesar, also known as "Oldiais" is one of the sixteen states of Palau. It is the sixth largest state in terms of land, with an area of roughly 40 square kilometers, and is located on the eastern side of Babeldaob Island. It is also northwest of Airai State, and southeast of Melekeok State, where the Pa- lau Government Capitol is situated. The sacred totem of Ngchesar is the Stingray. Ngchesar is famous for its war canoe "kabekel" named “bisebush” which means “lightning”. Vision “We, the people of Ngchesar desire to protect and conserve Mesekelat, Ngelukes and Ngchesar in its entirety to ensure that these natural assets are sustained for the benefits of the people of Ngchesar today and into the future.” The Ngchesar State Protected Area System was created with the support from the Ngchesar State Conservation Management Action Plan Team who identified a system of state protected areas in and around Ngchesar and with full endorsement by the community and the leadership of the State. In 2002, Ngchesar State Public Law NSPL No. 146 established Ngchesar State Protected Area System consisting of the following two conservation are- as: Ngelukes Conservation Area Ngelukes Conservation Area is a 1km patch reef in front of Ngersuul village. Ngelukes’s substrate is mostly sand and rubble. Its interior is characterized by sea grass beds. Most of the corals in this patch reef are found along its outer edges along with macroalgae covered rubble. It is a shallow reef, howev- er at its edge there are depths that reach 20 feet at maximum high tide. -

Republic of Palau Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan, 2007-2012

National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007 - 2012 R National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 To all Palauans, who make the Cancer Journey May their suffering return as skills and knowledge So that the people of Palau and all people can be Cancer Free! Special Thanks to The planning groups and their chairs whose energy, Interest and dedication in working together to develop the road map for cancer care in Palau. We also would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Grant # U55-CCU922043) National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 October 15, 2006 Dear Colleagues, This is the National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau. The National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau provides a road map for nation wide cancer prevention and control strategies from 2007 through to 2012. This plan is possible through support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA), the Ministry of Health (Palau) and OMUB (Community Advisory Group, Palau). This plan is a product of collaborative work between the Ministry of Health and the Palauan community in their common effort to create a strategic plan that can guide future activities in preventing and controlling cancers in Palau. The plan was designed to address prevention, early detection, treatment, palliative care strategies and survivorship support activities. The collaboration between the health sector and community ensures a strong commitment to its implementation and evaluation. The Republic of Palau trusts that you will find this publication to be a relevant and useful reference for information or for people seeking assistance in our common effort to reduce the burden of cancer in Palau. -

Airai State Government V. Iluches, 6 ROP Intrm. 57

Airai State Government v. Iluches, 6 ROP Intrm. 57 (1997) AIRAI STATE GOVERNMENT and AIRAI STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY (ASPLA), both represented herein by GOVERNOR, CHARLES I. OBICHANG who is also Chairman of ASPLA, Appellants, v. TITUS ILUCHES, ROMAN TMETUCHL, and TATSUO KAMINGAKI, Appellees. CIVIL APPEAL NO. 26-95 Civil Action No. 120-94 Supreme Court, Appellate Division Republic of Palau Opinion Decided: January 30, 1997 Counsel for Appellants: John K. Rechucher. ⊥58 Counsel for Appellees: Johnson Toribiong BEFORE: ARTHUR NGIRAKLSONG, Chief Justice; JEFFREY L. BEATTIE, Associate Justice; LARRY W. MILLER Associate Justice MILLER, Justice: In this action, Airai State Government and Airai State Public Lands Authority (ASPLA) seek to invalidate a lease previously entered into by ASPLA prior to the invalidation of the first Airai Constitution in the Teriong case. Looking backward from Teriong, they contend that the lease is invalid because the then-existing Airai State Government and ASPLA were invalid governmental entities at the time the lease was entered into. The trial court rejected this contention and they now appeal. We affirm. BACKGROUND The facts of this case are not in dispute. In 1985, Roman Tmetuchl, in his capacity as governor, applied for and received a permit to dredge and fill submerged coastal land near the Koror-Babeldaob Bridge in Airai; this “fill land” was to be the site of the Airai State Marina. On May 1, 1987, Tmetuchl, in his personal capacity, entered into a long-term lease agreement with ASPLA under which he obtained the right to use the subject land for a term of 99 years at a rate Airai State Government v.