Airai State Government V. Iluches, 6 ROP Intrm. 57

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

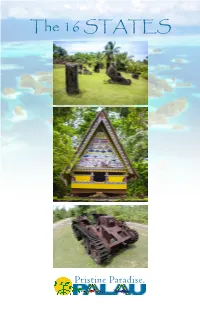

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Nakatani V. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) NORIYOSHI NAKATANI and NAKATANI CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Respondents

Nakatani v. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) NORIYOSHI NAKATANI and NAKATANI CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Respondents, v. MASAO NISHIZONO and SEIBU DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, Appellants, and REPUBLIC OF PALAU, Additional Appellant, and PACIFICA DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, a Palau Corporation. MASAO NISHIZONO, aka KWON BOO SIK CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Appellant, v. ROMAN TMETUCHL, MELWERT TMETUCHL, and NORIYOSHI NAKATANI, Respondents, and ⊥8 REPUBLIC OF PALAU, Additional Appellant, and PACIFICA DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION a Palau Corporation, Respondent. CIVIL APPEAL NO. 5-86 Civil Action No. 25-85 and Civil Action No. 73-85 (consolidated) Supreme Court, Appellate Division Republic of Palau Opinion Decided: January 8, 1990 Nakatani v. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) Counsel for Appellants Masao Nishizono and Seibu Development Corporation: James S. Brooks Counsel for Respondents Noriyoshi Nakatani and Nakatani Company: John S. Tarkong Counsel for Appellant Republic of Palau: Richard Brungard, Acting Attorney General. Counsel for Appellee Pacifica Development Corp. and Melwert Tmetuchl and Respondents Roman Tmetuchl and Airai State Gov’t.: Johnson Toribiong BEFORE: ALEX R. MUNSON,1 Associate Justice; ROBERT A. HEFNER,2 Associate Justice; FREDERICK J. O’BRIEN, Associate Justice Pro Tem. ⊥9 PER CURIAM: As will be seen, the issues presented for this appeal are limited in scope and therefore an extensive dissertation as to the factual and procedural history for this protracted litigation is unnecessary. Only the background necessary for the resolution of the issues raised for this appellate panel need be set forth in any detail. BACKGROUND Civil Action No. 73-85 was commenced on May 9, 1985, when plaintiffs Noriyoshi Nakatani and Nakatani Construction Co. (Nakatani) filed their complaint against Masao Nishizono, AKA Kwon Boo Sik (Nishizono), Seibu Development Corporation, Seibu Sohgo Kaihatsu, Hisayuki Kojima, Airai State, and Roman Tmetuchl, individually and as Governor of Airai State. -

The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future

OIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIA The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future The Republic of Palau is located roughly 500 miles east of the Philippines in the Western Pacific Ocean. The country consists of 189 square miles of land spread over more than 340 islands, only nine of which are inhabited: 95% of the land area lies within a single reef structure that includes the islands of Babeldaob (a.k.a. Babelthuap), Peleliu and Koror. Palau and the United States have a strong relationship as enshrined in the Compact of Free Association, U.S. Public Law 99-658. Palau has made a concerted effort in goals set forth in its energy policy. recent years to address the technical, The country completed its National policy, social and economic hurdles Climate Change Policy in 2015 and Energy & Climate Facts to deploying energy efficiency and made a commitment to reduce Total capacity (2015): 40.1 MW renewable energy technologies, and has national greenhouse gas emissions Diesel: 38.8 MW taken measures to mitigate and adapt to (GHGs) as part of the United Nations Solar PV: 1.3 MW climate change. This work is grounded in Framework Convention on Climate Total generation (2014): 78,133 MWh Palau’s 2010 National Energy Policy. Change (UNFCCC). Demand for electricity (2015): Palau has also developed an energy action However with a population of just Average/Peak: 8.9/13.5 MW plan to outline concrete steps the island over 21,000 and a gross national GHG emissions per capita: 13.56 tCO₂e nation could take to achieve the energy income per capita of only US$11,110 (2011) in 2014, Palau will need assistance Residential electric rate: $0.28/kWh 7°45|N (2013 average) Arekalong from the international community in REPUBLIC Peninsula order to fully implement its energy Population (2015): 21,265 OF PALAU and climate goals. -

A Summary of Palau's Typhoon History 1945-2013

A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History 1945-2013 Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau Dec, 2014 © Coral Reef Research Foundation 2014 Suggested citation: Coral Reef Research Foundation, 2014. A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History. Technical Report, 17pp. www.coralreefpalau.org Additions and suggestions welcome. Please email: [email protected] 2 Summary: Since 1945 Palau has had 68 recorded typhoons, tropical storms or tropical depressions come within 200 nmi of its islands or reefs. At their nearest point to Palau, 20 of these were typhoon strength with winds ≥64kts, or an average of 1 typhoon every 3 years. November and December had the highest number of significant storms; July had none over 40 kts and August had no recorded storms. Data Compilation: Storms within 200 nmi (nautical miles) of Palau were identified from the Digital Typhoon, National Institute of Informatics, Japan web site (http://agora.ex.nii.ac.jp/digital- typhoon/reference/besttrack.html.en). The storm tracks and intensities were then obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) (https://metoc.ndbc.noaa.gov/en/JTWC/). Three storm categories were used following the JTWC: Tropical Depression, winds ≤ 33 kts; Tropical Storm, winds 34-63 kts; Typhoon ≥64kts. All track data was from the JTWC archives. Tracks were plotted on Google Earth and the nearest distance to land or reef, and bearing from Palau, were measured; maximum sustained wind speed in knots (nautical miles/hr) at that point was recorded. Typhoon names were taken from the Digital Typhoon site, but typhoon numbers for the same typhoon were from the JTWC archives. -

Personnel - Johnston, Edward (2)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 39, folder “Personnel - Johnston, Edward (2)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 39 of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMIN I STRATION Presidential Libraries Withdrawal Sheet WITHDRAWAL ID 01510 REASON FOR WITHDRAWAL . Donor restriction TYPE OF MATERIAL Letter(s) CREATOR'S NAME . Thorpe, Richard RECEIVER'S NAME .... President DESCRIPTION . Trust Territory CREATION DATE 09/ 06/ 1974 COLLECTION/ SERIES/FOLDER ID 001900428 COLLECTION TITLE . Philip W. Buchen Files BOX NUMBER . 39 FOLDER TITLE . Personnel - Johnston, Edward ( 1)-(2) DATE WITHDRAWN . 08/ 26 / 1988 WITHDRAWING ARCHIVIST . LET NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION Presidential Libraries Withdrawal Sheet WITHDRAWAL ID 01511 REASON FOR WITHDRAWAL . Donor restriction TYPE OF MATERIAL Notes CREATOR'S NAME . Daughtrey, Eva DESCRIPTION Note for the file concerning Robert Thorpe phone calls . CREATION DATE . 06/24/1976 COLLECTION/SERIES/FOLDER ID . -

The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau

THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF INITIAL HUMAN SETTLEMENT IN PALAU, WESTERN MICRONESIA by JESSICA H. STONE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jessica H. Stone Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Anthropology by: Scott M. Fitzpatrick Chairperson Nelson Ting Core Member Dennis H. O’Rourke Core Member Stephen R. Frost Core Member James Watkins Institutional Representative and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020 ii © 2020 Jessica H. Stone iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Jessica H. Stone Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology June 2020 Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia The initial settlement of Remote Oceania represents the world’s last major wave of human dispersal. While transdisciplinary models involving linguistic, archaeological, and biological data have been utilized in the Pacific to develop basic chronologies and trajectories of initial human settlement, a number of elusive gaps remain in our understanding of the region’s colonization history. This is especially true in Micronesia, where a paucity of human skeletal material dating to the earliest periods of settlement have hindered biological contributions to colonization models. The Chelechol ra Orrak site in Palau, western Micronesia, contains the largest and oldest human skeletal assemblage in the region, and is one of only two known sites that represent some of the earliest settlers in the Pacific. -

Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau

THREA TENED ENDEMIC PLANTS OF PALAU BIODI VERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 19: Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Craig Costion, James Cook University, Australia Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Photo credits: Craig Costion (unless cited otherwise) Cover photograph: Parkia flowers. © Craig Costion Series Editors: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, -

Noteworthy Micronesian Plants. 3

Noteworthy Micronesian Plants. 3. F. R. FOSBERG and JOANE. CANFIELD Department of Botany , National Museum of N atural History , Smith sonian Institution, Washin gton, D.C. 20560 This third paper of this series contains new distributional records and taxonomic notes mainly on the plants of the Palau Islands. Range extensions are recorded in the genera Hymenophyllum, Trichomanes, Schizaea, Cyclopeltis, Dipla zium, Humata, Nephrolepis, Apluda, Panicum, Pennisetum, Setaria , Sporobolus, Fimbristylis, Aneilema, Suriana, Xylocarpus , Euphorbia, M elanolepis, Ammannia , Melaleuca, Bacopa, Utricularia, Andrographis, Hedyotis, Sp ermacoce, Timonius and Youngia. Taxonomic notes are presented on Humata, Nephrolepis, Aneilema, Eriocaulon, Piriqueta, Eugenia, Leucas, Hedyotis, and Spermacoce . HYMENOPHYLLACEAE Hymenophyllum serrulatum (Pres!) C. Chr. , Ind . Fil. 367 , 1905. A delicate Malesian epiphyte with frond 6 - 8(- 30) cm long ; indusium lips bluntly triangular, receptacle protruding when old. It is distinguished from the more common H. polyanthos by the toothed rather than entire margin of the lobes and the bluntly triangular rather than ovate lips of the indusium. This constitutes a first record for Micronesia . CAROLINEISLANDS : Palau: Babeldaob I., W. Ngeremlengui Murrie ., locally abundant in forest below peak 1.7 mi. (2. 7 km) ESE of Almongui Pt. , I 00 m, 7 Dec . 1978, Canfield 613 (US). Trichomanes setigerum Backhouse Cat. 14, 1861. Moore, Gard. Chron . 1862: 45 , 1962. Holttum , Fl, Malaya 2: 104-105, 1954 . This species, with very finely dissected fronds , has previously been found in Borneo, Malaya, and Pala wan in the Philippines, according to Holttum , who places it in Trichomanes sect. Macroglena (Copeland's genus Macroglena), where it seems to fit well enough. It is a distinct surprise to find it in Palau . -

Pacific Freely Associated States Include the Republic Low Coral Islands (Figure FAS-1)

NOAA Coral Reef Ecosystem Research Plan PACIFIC FREELY Republic of the Marshall Islands ASSOCIATED STATES The Marshall Islands encompasses approximately 1,225 individual islands and islets, with 29 atolls and 5 solitary The Pacific Freely Associated States include the Republic low coral islands (Figure FAS-1). The Marshalls have a 2 of the Marshall Islands (the Marshalls), the Federated total dry land area of only about 181.3 km . However, States of Micronesia (FSM), and the Republic of Palau when the Exclusive Economic Zone (from the shoreline (Palau). These islands are all independent countries that to 200 miles offshore) is considered, the Republic covers 2 at one-time were governed by the U. S. as part of the Trust 1,942,000 km of ocean within the larger Micronesia 2 Territory of the Pacific Islands after World War II. Although region. There are 11,670 km of sea within the lagoons these countries are independent, they still maintain close of the atolls. Land makes up less than 0.01% of the ties with the U.S. and are eligible to receive funds from area of the Marshalls. Most of the country is the broad U.S. Federal agencies, including NOAA, DOI, EPA, and the open ocean with a seafloor depth that reaches 4.6 km. National Science Foundation. Scattered throughout the Marshalls are nearly 100 isolated submerged volcanic seamounts; those with flattened tops The coral reef resources of these islands remain are called guyots. The average elevation of the Marshalls mostly unmapped. is about 2 m above sea level. In extremely dry years, there may be no precipitation on some of the drier atolls. -

Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences

STREAMS - Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences WSU Boonshoft School of Medicine 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway Dayton, OH 45435-0001 APPLICATION (please type or print legibly) *Required information *Name_____________________________________ Social Security #____________________________________ *Undergraduate Institution_______________________________________________________________________ *Date of Birth: Class: Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Post-bac Major_____________________________________ Expected date of graduation___________________________ SAT (or ACT) scores: VERB_________MATH_________Test Date_________GPA__________ *Applicant’s Current Mailing Address *Mailing Address After ____________(Give date) _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ *Email Address:_____________________________ FAX number: (____)_______________________ Where did you learn about this program?:__________________________________________________________ *Are you a U.S. citizen or permanent resident? Yes No (You must be a citizen or permanent resident to participate in this program) *Please indicate the group(s) in which you would include yourself: Native American/Alaskan Native Black/African-American -

2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU APPELLATE DIVISION NGEREMLENGUI STATE GOVERNMENT and NGEREMLENGUI STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellants/Cross-Appellees, v. NGARDMAU STATE GOVERNMENT and NGARDMAU STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellees/Cross-Appellants. Cite as: 2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No. 15-014 Appeal from Civil Action No. 13-020 Decided: November 16, 2016 Counsel for Ngeremlengui ............................................... Oldiais Ngiraikelau Counsel for Ngardmau ..................................................... Yukiwo P. Dengokl Matthew S. Kane BEFORE: KATHLEEN M. SALII, Associate Justice LOURDES F. MATERNE, Associate Justice C. QUAY POLLOI, Associate Justice Pro Tem Appeal from the Trial Division, the Honorable R. Ashby Pate, Associate Justice, presiding. OPINION PER CURIAM: [¶ 1] This appeal arises from a dispute between the neighboring States of Ngeremlengui and Ngardmau regarding their common boundary line. In 2013, the Ngeremlengui State Government and Ngeremlengui State Public Lands Authority (Ngeremlengui) filed a civil suit against the Ngardmau State Government and Ngardmau State Public Lands Authority (Ngardmau), seeking a judgment declaring the legal boundary line between the two states. After extensive evidentiary proceedings and a trial, the Trial Division issued a decision adjudging that common boundary line. [¶ 2] Each state has appealed a portion of that decision and judgment. Ngardmau argues that the Trial Division applied an incorrect legal standard to determine the boundary line. Ngardmau also argues that the Trial Division Ngeremlengui v. Ngardmau, 2016 Palau 24 clearly erred in making factual determinations concerning parts of the common land boundary. Ngeremlengui argues that the Trial Division clearly erred in making factual determinations concerning a part of the common maritime boundary. For the reasons below, the judgment of the Trial Division is AFFIRMED. -

Ngchesar State Protected Areas | PAN Site Mesekelat and Ngelukes Conservation Area Ngchesar State Vision Ngelukes Conservation A

Ngchesar State Protected Areas | PAN Site Mesekelat and Ngelukes Conservation Area January 2016 │ Fact Sheet Ngchesar State Ngchesar, also known as "Oldiais" is one of the sixteen states of Palau. It is the sixth largest state in terms of land, with an area of roughly 40 square kilometers, and is located on the eastern side of Babeldaob Island. It is also northwest of Airai State, and southeast of Melekeok State, where the Pa- lau Government Capitol is situated. The sacred totem of Ngchesar is the Stingray. Ngchesar is famous for its war canoe "kabekel" named “bisebush” which means “lightning”. Vision “We, the people of Ngchesar desire to protect and conserve Mesekelat, Ngelukes and Ngchesar in its entirety to ensure that these natural assets are sustained for the benefits of the people of Ngchesar today and into the future.” The Ngchesar State Protected Area System was created with the support from the Ngchesar State Conservation Management Action Plan Team who identified a system of state protected areas in and around Ngchesar and with full endorsement by the community and the leadership of the State. In 2002, Ngchesar State Public Law NSPL No. 146 established Ngchesar State Protected Area System consisting of the following two conservation are- as: Ngelukes Conservation Area Ngelukes Conservation Area is a 1km patch reef in front of Ngersuul village. Ngelukes’s substrate is mostly sand and rubble. Its interior is characterized by sea grass beds. Most of the corals in this patch reef are found along its outer edges along with macroalgae covered rubble. It is a shallow reef, howev- er at its edge there are depths that reach 20 feet at maximum high tide.