The Use Offlaked Stone Artifacts in Palau) Western Micronesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

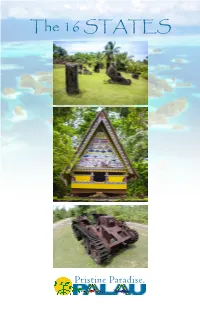

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

A Summary of Palau's Typhoon History 1945-2013

A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History 1945-2013 Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau Dec, 2014 © Coral Reef Research Foundation 2014 Suggested citation: Coral Reef Research Foundation, 2014. A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History. Technical Report, 17pp. www.coralreefpalau.org Additions and suggestions welcome. Please email: [email protected] 2 Summary: Since 1945 Palau has had 68 recorded typhoons, tropical storms or tropical depressions come within 200 nmi of its islands or reefs. At their nearest point to Palau, 20 of these were typhoon strength with winds ≥64kts, or an average of 1 typhoon every 3 years. November and December had the highest number of significant storms; July had none over 40 kts and August had no recorded storms. Data Compilation: Storms within 200 nmi (nautical miles) of Palau were identified from the Digital Typhoon, National Institute of Informatics, Japan web site (http://agora.ex.nii.ac.jp/digital- typhoon/reference/besttrack.html.en). The storm tracks and intensities were then obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) (https://metoc.ndbc.noaa.gov/en/JTWC/). Three storm categories were used following the JTWC: Tropical Depression, winds ≤ 33 kts; Tropical Storm, winds 34-63 kts; Typhoon ≥64kts. All track data was from the JTWC archives. Tracks were plotted on Google Earth and the nearest distance to land or reef, and bearing from Palau, were measured; maximum sustained wind speed in knots (nautical miles/hr) at that point was recorded. Typhoon names were taken from the Digital Typhoon site, but typhoon numbers for the same typhoon were from the JTWC archives. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau

THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF INITIAL HUMAN SETTLEMENT IN PALAU, WESTERN MICRONESIA by JESSICA H. STONE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jessica H. Stone Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Anthropology by: Scott M. Fitzpatrick Chairperson Nelson Ting Core Member Dennis H. O’Rourke Core Member Stephen R. Frost Core Member James Watkins Institutional Representative and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020 ii © 2020 Jessica H. Stone iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Jessica H. Stone Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology June 2020 Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia The initial settlement of Remote Oceania represents the world’s last major wave of human dispersal. While transdisciplinary models involving linguistic, archaeological, and biological data have been utilized in the Pacific to develop basic chronologies and trajectories of initial human settlement, a number of elusive gaps remain in our understanding of the region’s colonization history. This is especially true in Micronesia, where a paucity of human skeletal material dating to the earliest periods of settlement have hindered biological contributions to colonization models. The Chelechol ra Orrak site in Palau, western Micronesia, contains the largest and oldest human skeletal assemblage in the region, and is one of only two known sites that represent some of the earliest settlers in the Pacific. -

Homecoming Festivities to Begin Tonight Beaver Club Givesofficers Tapped SWING MAESTRO Dances In

HOLIDAY WELCOME TOMORROW W$t Batoiteoman ALUMNI AkENDA LUX UBI ORTA LIBERTAS Volume XXXV DAVIDSON COLLEGE, DAVIDSON^**. C FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 1946 No. S Homecoming Festivities To Begin Tonight Beaver Club GivesOfficers Tapped SWING MAESTRO Dances In ' "* * v # 1''' ■ -...■ . '■.'■[.;^"l ■ l n , Bids To New MenBy Military Frat . "^fl^^3fl|JB^$ i !'v~ Charlotte Honorary Underclass Frat Scabbard and Hlade Chooses Pretty "I'at" Connor Will Be Takes Eleven FEATURED Eleven Members Start Made On Ky Dave Richardson Vocalist With Kutterfield On Thursday, October 24, David- Orchestra son's Beaver Club held its annual Amassing a display of military splendor unequalled on the David- tap day, bidding new men from the New Magazine son campus since the Enlisted Re- "What's New?" is not only Billy Sophomore and Junior classes. The Scripts 'n Pranks, the revived serve Corps saved countless num- Butterfield's theme song but he is organization, an honorary frater- college magazine, willhave its first bers of students from the draft in also what is news today. Billy nity for underclassmen, judges pro- edition this year in December, ap- 1943. the R. 0. T. ('. battalion held Butterfield is the young master of parade of year spective candidates for membership proximately one week before the its first the Tues- the trumpet who has blown his Christmas Successive is- day as part of the ceremony of -on leadership, scholarship, and ath- vacation. horn straight sues will appear in February, April, tapping new members for Scabbard to the top and, as ability. result, letic New members from and May of next year. -

Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau

THREA TENED ENDEMIC PLANTS OF PALAU BIODI VERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 19: Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Craig Costion, James Cook University, Australia Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Photo credits: Craig Costion (unless cited otherwise) Cover photograph: Parkia flowers. © Craig Costion Series Editors: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, -

Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873 Margaret A

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 5-1993 Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873 Margaret A. Field University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Native American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Field, Margaret A., "Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873" (1993). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 141. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENOCIDE AND THE INDIANS OF CALIFORNIA , 1769-1873 A Thesis Presented by MARGARET A. FIELD Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies and Research of the Un1versity of Massachusetts at Boston in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS MAY 1993 HISTCRY PROGRAM GENOCIDE AND THE I NDIAN S OF CALIFORNIA, 1769-187 3 A Thesis P resented by MARGARET A. FIELD Approved as to style and content by : Clive Foss , Professor Co - Chairperson of Committee mes M. O'Too le , Assistant Professor -Chairpers on o f Committee Memb e r Ma rshall S. Shatz, Pr og~am Director Department of History ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank professors Foss , O'Toole, and Buckley f or their assistance in preparing this manuscri pt and for their encouragement throughout the project . -

Noteworthy Micronesian Plants. 3

Noteworthy Micronesian Plants. 3. F. R. FOSBERG and JOANE. CANFIELD Department of Botany , National Museum of N atural History , Smith sonian Institution, Washin gton, D.C. 20560 This third paper of this series contains new distributional records and taxonomic notes mainly on the plants of the Palau Islands. Range extensions are recorded in the genera Hymenophyllum, Trichomanes, Schizaea, Cyclopeltis, Dipla zium, Humata, Nephrolepis, Apluda, Panicum, Pennisetum, Setaria , Sporobolus, Fimbristylis, Aneilema, Suriana, Xylocarpus , Euphorbia, M elanolepis, Ammannia , Melaleuca, Bacopa, Utricularia, Andrographis, Hedyotis, Sp ermacoce, Timonius and Youngia. Taxonomic notes are presented on Humata, Nephrolepis, Aneilema, Eriocaulon, Piriqueta, Eugenia, Leucas, Hedyotis, and Spermacoce . HYMENOPHYLLACEAE Hymenophyllum serrulatum (Pres!) C. Chr. , Ind . Fil. 367 , 1905. A delicate Malesian epiphyte with frond 6 - 8(- 30) cm long ; indusium lips bluntly triangular, receptacle protruding when old. It is distinguished from the more common H. polyanthos by the toothed rather than entire margin of the lobes and the bluntly triangular rather than ovate lips of the indusium. This constitutes a first record for Micronesia . CAROLINEISLANDS : Palau: Babeldaob I., W. Ngeremlengui Murrie ., locally abundant in forest below peak 1.7 mi. (2. 7 km) ESE of Almongui Pt. , I 00 m, 7 Dec . 1978, Canfield 613 (US). Trichomanes setigerum Backhouse Cat. 14, 1861. Moore, Gard. Chron . 1862: 45 , 1962. Holttum , Fl, Malaya 2: 104-105, 1954 . This species, with very finely dissected fronds , has previously been found in Borneo, Malaya, and Pala wan in the Philippines, according to Holttum , who places it in Trichomanes sect. Macroglena (Copeland's genus Macroglena), where it seems to fit well enough. It is a distinct surprise to find it in Palau . -

Pacific Freely Associated States Include the Republic Low Coral Islands (Figure FAS-1)

NOAA Coral Reef Ecosystem Research Plan PACIFIC FREELY Republic of the Marshall Islands ASSOCIATED STATES The Marshall Islands encompasses approximately 1,225 individual islands and islets, with 29 atolls and 5 solitary The Pacific Freely Associated States include the Republic low coral islands (Figure FAS-1). The Marshalls have a 2 of the Marshall Islands (the Marshalls), the Federated total dry land area of only about 181.3 km . However, States of Micronesia (FSM), and the Republic of Palau when the Exclusive Economic Zone (from the shoreline (Palau). These islands are all independent countries that to 200 miles offshore) is considered, the Republic covers 2 at one-time were governed by the U. S. as part of the Trust 1,942,000 km of ocean within the larger Micronesia 2 Territory of the Pacific Islands after World War II. Although region. There are 11,670 km of sea within the lagoons these countries are independent, they still maintain close of the atolls. Land makes up less than 0.01% of the ties with the U.S. and are eligible to receive funds from area of the Marshalls. Most of the country is the broad U.S. Federal agencies, including NOAA, DOI, EPA, and the open ocean with a seafloor depth that reaches 4.6 km. National Science Foundation. Scattered throughout the Marshalls are nearly 100 isolated submerged volcanic seamounts; those with flattened tops The coral reef resources of these islands remain are called guyots. The average elevation of the Marshalls mostly unmapped. is about 2 m above sea level. In extremely dry years, there may be no precipitation on some of the drier atolls. -

Microbiological Spoilage of Fruits and Vegetables

Microbiological Spoilage of Fruits and Vegetables Margaret Barth, Thomas R. Hankinson, Hong Zhuang, and Frederick Breidt Introduction Consumption of fruit and vegetable products has dramatically increased in the United States by more than 30% during the past few decades. It is also estimated that about 20% of all fruits and vegetables produced is lost each year due to spoilage. The focus of this chapter is to provide a general background on microbiological spoilage of fruit and vegetable products that are organized in three categories: fresh whole fruits and vegetables, fresh-cut fruits and vegetables, and fermented or acidified veg- etable products. This chapter will address characteristics of spoilage microorgan- isms associated with each of these fruit and vegetable categories including spoilage mechanisms, spoilage defects, prevention and control of spoilage, and methods for detecting spoilage microorganisms. Microbiological Spoilage of Fresh Whole Fruits and Vegetables Introduction During the period 1970–2004, US per capita consumption of fruits and vegetables increased by 19.9%, to 694.3 pounds per capita per year (ERS, 2007). Fresh fruit and vegetable consumption increased by 25.8 and 32.6%, respectively, and far exceeded the increases observed for processed fruit and vegetable products. If US consump- tion patterns continue in this direction, total per capita consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables would surpass consumption of processed fruits and vegetables within the next decade. This shift toward overall increased produce consumption can be attributed, at least in part, to increased awareness in healthy eating habits as revealed by a broad field of research addressing food consumption and health and promoted by the M. -

Preliminary Draft

Title preliminary D R A F T -- 1/91 D-Day, Orange Beach 3 BLILIOU (PELELIU) HISTORICAL PARK STUDY January, 1991 Preliminary Draft Prepared by the Government of Palau and the http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/peleliu/title.htm[7/24/2013 3:39:42 PM] Title National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Background and Purpose BLILIOU (PELELIU) Study Setting Tourism Land Ownership and Tenure in Palau Compact of Free Association Bliliou Consultation and Coordination World War II Relics on Bliliou Natural Resources on Bliliou Bliliou National Historic Landmark Historical Park - Area Options Management Plan Bliliou Historical Park Development THE ROCK ISLANDS OF PALAU http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/peleliu/title.htm[7/24/2013 3:39:42 PM] Title Description The Reefs The Islands Soils Vegetation The Lagoon Marine Lakes Birdlife Scenery Archeology Existing Uses Recreation Fishing Land Use Conserving and Protecting Rock Islands Resources Management Concepts Boundary Options PARK PROTECTION POSSIBILITIES BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDICES Appendix A Appendix B http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/peleliu/title.htm[7/24/2013 3:39:42 PM] Title Management Option Costs LIST OF FIGURES Figure Location Map, The Pacific Ocean 1 Figure States of the Republic of Palau 2 Figure Peleliu 1944; Bliliou Today 3 Figure Land Tenure 4 Figure Remaining Sites and Features, 1944 Invasion 5 Figure Detail 1, Scarlet Beach 6 Figure Detail 2, Purple Beach 7 Figure Detail 3, Amber Beach 8 Figure Detail 4, Amber Beach & Bloody Nose Ridge 9 Figure Detail 5, White and Orange Beaches 10 Figure Bloody -

Th E Rock Islands Southern Lagoon

T e Rock Islands Southern Lagoon as nominated by T e Republic of Palau for Inscription on the World Heritage List February 2012 1 This dossier is dedicated to Senator Adalbert Eledui 2 Rock Islands Southern Lagoon, Republic of Palau 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................5 1. Identifi cation of the Property .......................................................... 8 2. Description of the Property ............................................................13 Natural heritage ..........................................................................13 Cultural heritage ..........................................................................26 2. History and Development ..............................................................46 3. Justifi cation for Inscription .............................................................55 Criteria under which inscription is proposed ...................................55 Statement of Outstanding Universal Value ................................... 69 Comparative analysis ...................................................................72 Integrity and authenticity............................................................ 86 4. State of Conservation and Factors Aff ecting the Property .................91 Present state of conservation .......................................................91 Factors aff ecting the property..................................................... 100 5. Protection and Management of the Property