Article Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanisms of Salmonella Attachment and Survival on In-Shell Black Peppercorns, Almonds, and Hazelnuts

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Mechanisms of Salmonella Attachment and Survival on In-Shell Black Peppercorns, Almonds, and Hazelnuts. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5534264q Authors Li, Ye Salazar, Joelle K He, Yingshu et al. Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.3389/fmicb.2020.582202 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California fmicb-11-582202 October 19, 2020 Time: 10:46 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 23 October 2020 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.582202 Mechanisms of Salmonella Attachment and Survival on In-Shell Black Peppercorns, Almonds, and Hazelnuts Ye Li1, Joelle K. Salazar2, Yingshu He1, Prerak Desai3, Steffen Porwollik3, Weiping Chu3, Palma-Salgado Sindy Paola4, Mary Lou Tortorello2, Oscar Juarez5, Hao Feng4, Michael McClelland3* and Wei Zhang1* 1 Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Illinois Institute of Technology, Bedford Park, IL, United States, 2 Division of Food Processing Science and Technology, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Bedford Park, IL, United States, 3 Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States, 4 Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 5 Department Edited by: of Biology, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL, United States Chrysoula C. Tassou, Institute of Technology of Agricultural Products, Hellenic Agricultural Salmonella enterica subspecies I (ssp 1) is the leading cause of hospitalizations and Organization, Greece deaths due to known bacterial foodborne pathogens in the United States and is Reviewed by: frequently implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks associated with spices and nuts. -

Exoribonuclease Nibbler Shapes the 3″ Ends of Micrornas

Current Biology 21, 1878–1887, November 22, 2011 ª2011 Elsevier Ltd All rights reserved DOI 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.034 Article The 30-to-50 Exoribonuclease Nibbler Shapes the 30 Ends of MicroRNAs Bound to Drosophila Argonaute1 Bo W. Han,1 Jui-Hung Hung,2 Zhiping Weng,2 precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) [8]. Pre-miRNAs comprise Phillip D. Zamore,1,* and Stefan L. Ameres1,* a single-stranded loop and a partially base-paired stem whose 1Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department of termini bear the hallmarks of RNase III processing: a two-nucle- Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology otide 30 overhang, a 50 phosphate, and a 30 hydroxyl group. 2Program in Bioinformatics and Integrative Biology Nuclear pre-miRNAs are exported by Exportin 5 to the cyto- University of Massachusetts Medical School, plasm, where the RNase III enzyme Dicer liberates w22 nt 364 Plantation Street, Worcester, MA 01605, USA mature miRNA/miRNA* duplexes from the pre-miRNA stem [9–12]. Like all Dicer products, miRNA duplexes contain two- nucleotide 30 overhangs, 50 phosphate, and 30 hydroxyl groups. Summary In flies, Dicer-1 cleaves pre-miRNAs to miRNAs, whereas Dicer-2 converts long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into Background: MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are w22 nucleotide (nt) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which direct RNA interference small RNAs that control development, physiology, and pathol- (RNAi), a distinct small RNA silencing pathway required for ogy in animals and plants. Production of miRNAs involves the host defense against viral infection and somatic transposon sequential processing of primary hairpin-containing RNA poly- mobilization, as well as gene silencing triggered by exogenous merase II transcripts by the RNase III enzymes Drosha in the dsRNA [13, 14]. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

Characterization of the Mammalian RNA Exonuclease 5/NEF-Sp As a Testis-Specific Nuclear 3′′′′′ → 5′′′′′ Exoribonuclease

Downloaded from rnajournal.cshlp.org on October 7, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Characterization of the mammalian RNA exonuclease 5/NEF-sp as a testis-specific nuclear 3′′′′′ → 5′′′′′ exoribonuclease SARA SILVA,1,2 DAVID HOMOLKA,1 and RAMESH S. PILLAI1 1Department of Molecular Biology, University of Geneva, CH-1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland 2European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Grenoble Outstation, 38042, France ABSTRACT Ribonucleases catalyze maturation of functional RNAs or mediate degradation of cellular transcripts, activities that are critical for gene expression control. Here we identify a previously uncharacterized mammalian nuclease family member NEF-sp (RNA exonuclease 5 [REXO5] or LOC81691) as a testis-specific factor. Recombinant human NEF-sp demonstrates a divalent metal ion-dependent 3′′′′′ → 5′′′′′ exoribonuclease activity. This activity is specific to single-stranded RNA substrates and is independent of their length. The presence of a 2′′′′′-O-methyl modification at the 3′′′′′ end of the RNA substrate is inhibitory. Ectopically expressed NEF-sp localizes to the nucleolar/nuclear compartment in mammalian cell cultures and this is dependent on an amino-terminal nuclear localization signal. Finally, mice lacking NEF-sp are viable and display normal fertility, likely indicating overlapping functions with other nucleases. Taken together, our study provides the first biochemical and genetic exploration of the role of the NEF-sp exoribonuclease in the mammalian genome. Keywords: NEF-sp; LOC81691; Q96IC2; REXON; RNA exonuclease 5; REXO5; 2610020H08Rik INTRODUCTION clease-mediated processing to create their final 3′ ends: poly(A) tails of most mRNAs or the hairpin structure of Spermatogenesis is the process by which sperm cells are replication-dependent histone mRNAs (Colgan and Manley produced in the male germline. -

BRCA1 Binds TERRA RNA and Suppresses R-Loop-Based Telomeric DNA Damage ✉ Jekaterina Vohhodina 1,2 , Liana J

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23716-6 OPEN BRCA1 binds TERRA RNA and suppresses R-Loop-based telomeric DNA damage ✉ Jekaterina Vohhodina 1,2 , Liana J. Goehring1, Ben Liu1,2, Qing Kong1,2, Vladimir V. Botchkarev Jr.1,2, Mai Huynh1, Zhiqi Liu1, Fieda O. Abderazzaq1,2, Allison P. Clark1,2, Scott B. Ficarro1,3,4,5, Jarrod A. Marto 1,3,4,5, ✉ Elodie Hatchi 1,2 & David M. Livingston 1,2 R-loop structures act as modulators of physiological processes such as transcription termi- 1234567890():,; nation, gene regulation, and DNA repair. However, they can cause transcription-replication conflicts and give rise to genomic instability, particularly at telomeres, which are prone to forming DNA secondary structures. Here, we demonstrate that BRCA1 binds TERRA RNA, directly and physically via its N-terminal nuclear localization sequence, as well as telomere- specific shelterin proteins in an R-loop-, and a cell cycle-dependent manner. R-loop-driven BRCA1 binding to CpG-rich TERRA promoters represses TERRA transcription, prevents TERRA R-loop-associated damage, and promotes its repair, likely in association with SETX and XRN2. BRCA1 depletion upregulates TERRA expression, leading to overly abundant TERRA R-loops, telomeric replication stress, and signs of telomeric aberrancy. Moreover, BRCA1 mutations within the TERRA-binding region lead to an excess of TERRA-associated R- loops and telomeric abnormalities. Thus, normal BRCA1/TERRA binding suppresses telomere-centered genome instability. 1 Department of Cancer Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA. 2 Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. 3 Blais Proteomics Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA. -

Role for Cytoplasmic Nucleotide Hydrolysis in Hepatic Function and Protein Synthesis

Role for cytoplasmic nucleotide hydrolysis in hepatic function and protein synthesis Benjamin H. Hudson1, Joshua P. Frederick1, Li Yin Drake, Louis C. Megosh, Ryan P. Irving, and John D. York2,3 Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710 Edited by David W. Russell, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, and approved February 11, 2013 (received for review March 26, 2012) Nucleotide hydrolysis is essential for many aspects of cellular (5–7), which is degraded to 5′-AMP by a family of enzymes known function. In the case of 3′,5′-bisphosphorylated nucleotides, mam- as 3′-nucleotidases (8). mals possess two related 3′-nucleotidases, Golgi-resident 3′-phos- Mammalian genomes encode two 3′-nucleotidases, the recently phoadenosine 5′-phosphate (PAP) phosphatase (gPAPP) and characterized Golgi-resident PAP phosphatase (gPAPP) and Bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase 1 (Bpnt1). gPAPP and Bpnt1 localize Bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase 1 (Bpnt1), which localize to the to distinct subcellular compartments and are members of a con- Golgi lumen and cytoplasm, respectively (Fig. 1B)(8–11). gPAPP served family of metal-dependent lithium-sensitive enzymes. Al- and Bpnt1 are members of a family of small-molecule phospha- though recent studies have demonstrated the importance of tases whose activities are both dependent on divalent cations and gPAPP for proper skeletal development in mice and humans, the inhibited by lithium (8). The family comprises seven mammalian role of Bpnt1 in mammals remains largely unknown. Here we re- gene products: fructose bisphosphatase 1 and 2, inositol monophos- port that mice deficient for Bpnt1 do not exhibit skeletal defects phatase 1 and 2, inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase, gPAPP, but instead develop severe liver pathologies, including hypopro- and Bpnt1 (Fig. -

Biochemical Characterization of Exoribonuclease Encoded by SARS Coronavirus

Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Vol. 40, No. 5, September 2007, pp. 649-655 Biochemical Characterization of Exoribonuclease Encoded by SARS Coronavirus Ping Chen1, Miao Jiang1, Tao Hu1, Qingzhen Liu1, Xiaojiang S. Chen2 and Deyin Guo1,* 1State Key Laboratory of Virology and The Modern Virology Research Centre, College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, P.R. China 2Department of Molecular and Computational Biology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA Received 2 February 2007, Accepted 6 April 2007 The nsp14 protein is an exoribonuclease that is encoded by Many published sequences of SARS-CoV have provided severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS- important information on the 29.7 kb positive-strand RNA CoV). We have cloned and expressed the nsp14 protein in genome of SARS-CoV (Marra et al., 2003; Rota et al., 2003; Escherichia coli, and characterized the nature and the Ruan et al., 2003). Like other coronavirus, SARS-CoV gene role(s) of the metal ions in the reaction chemistry. The expression and genome replication require polyprotein synthesis purified recombinant nsp14 protein digested a 5'-labeled and subgenomic production (Miller and Koev, 2000; Ruan et RNA molecule, but failed to digest the RNA substrate that al., 2003; Snijder et al., 2003; Thiel et al., 2003; Hussain et is modified with fluorescein group at the 3'-hydroxyl al., 2005). group, suggesting a 3'-to-5' exoribonuclease activity. The Coronavirus replication in cells is initiated by translation of exoribonuclease activity requires Mg2+ as a cofactor. the two overlapping polyproteins that are proteolytically Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analysis indicated a processed to yield replication-associated proteins, including two-metal binding mode for divalent cations by nsp14. -

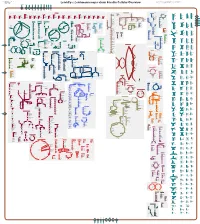

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Zheng Zhao, Delft University of Technology Marcel A. van den Broek, Delft University of Technology S. Aljoscha Wahl, Delft University of Technology Wilbert H. Heijne, DSM Biotechnology Center Roel A. Bovenberg, DSM Biotechnology Center Joseph J. Heijnen, Delft University of Technology An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Marco A. van den Berg, DSM Biotechnology Center Peter J.T. Verheijen, Delft University of Technology Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. PchrCyc: Penicillium rubens Wisconsin 54-1255 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Liang Wu, DSM Biotechnology Center Walter M. van Gulik, Delft University of Technology L-quinate phosphate a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar multidrug multidrug a dicarboxylate phosphate a proteinogenic 2+ 2+ + met met nicotinate Mg Mg a cation a cation K + L-fucose L-fucose L-quinate L-quinate L-quinate ammonium UDP ammonium ammonium H O pro met amino acid a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar K oxaloacetate L-carnitine L-carnitine L-carnitine 2 phosphate quinic acid brain-specific hypothetical hypothetical hypothetical hypothetical -

Exoribonuclease Xrn1 by Cofactor Dcs1 Is Essential for Mitochondrial Function in Yeast

Activation of 5′-3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1 by cofactor Dcs1 is essential for mitochondrial function in yeast Flore Sinturela,b, Dominique Bréchemier-Baeyb, Megerditch Kiledjianc, Ciarán Condonb, and Lionel Bénarda,b,1 aLaboratoire de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire des Eucaryotes, Institut de Biologie Physico-Chimique, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Formation de Recherche en Evolution (FRE) 3354, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, 75005 Paris, France; bLaboratoire de l’Expression Génétique Microbienne, Institut de Biologie Physico-Chimique, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Propre de Recherche 9073, Université de Paris 7-Denis-Diderot, 75005 Paris, France; and cDepartment of Cell Biology and Neuroscience, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854 Edited* by Reed B. Wickner, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved April 6, 2012 (received for review December 6, 2011) The scavenger decapping enzyme Dcs1 has been shown to facilitate Saccharomyces cerevisiae (16). Known regulatory RNAs belong to the activity of the cytoplasmic 5′-3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1 in eukar- this class, and their stabilization in the absence of Xrn1 could yotes. Dcs1 has also been shown to be required for growth in glyc- explain the aberrant expression of some genes. erol medium. We therefore wondered whether the capacity to Few studies have investigated how the activity of exoribonu- activate RNA degradation could account for its requirement for cleases is modulated in connection to cell physiology (17, 18). growth on this carbon source. Indeed, a catalytic mutant of Xrn1 Here, we focus on Dcs1, a factor that potentially controls the is also unable to grow in glycerol medium, and removal of the activity of the exoribonuclease Xrn1 (4). -

Title Comprehensive Classification of the Rnase H-Like Domain-Containing Proteins in Plants

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/572842; this version posted January 13, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Title Comprehensive Classification of the RNase H-like domain-containing Proteins in Plants Shuai Li, Kunpeng Liu, and Qianwen Sun# Tsinghua-Peking Joint Center for Life Sciences and Center for Plant Biology, School of Life Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China # Corresponding author Qianwen Sun: [email protected]. Abstract Background R-loop is a nucleic acid structure containing an RNA-DNA hybrid and a displaced single-stranded DNA. Recently, accumulated evidence showed that R-loops widely present in various organisms’ genomes and are involved in many physiological processes, including DNA replication, RNA transcription, and DNA repair. RNase H-like superfamily (RNHLS) domain-containing proteins, such as RNase H enzymes, are essential in restricting R-loop levels. However, little is known about the function and relationship of other RNHLS proteins on R-loop regulation, especially in plants. Results In this study, we characterized 6193 RNHLS proteins from 13 representative plant species and clustered these proteins into 27 clusters, among which reverse transcriptases and exonucleases are the two largest groups. Moreover, we found 691 RNHLS proteins in Arabidopsis with a conserved catalytic alpha-helix and beta-sheet motif. Interestingly, each of the Arabidopsis RNHLS proteins is composed of not only an RNHLS domain but also another different protein domain. -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Maria Doyle Ron Caspi James I Macrae An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Eleanor C Saunders Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. LeishCyc: Leishmania major strain Friedlin Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Malcolm J Mcconville D-fructose D-fructose D-fructose hypoxanthine inosine 1-alkyl-2-acyl-phosphatidylcholine D-galactose D-galactose D-fructose D-galactose xanthine spermidine guanosine a phosphatidylcholine myo-inositol D-mannose D-mannose D-mannose D-mannose adenine arg arg putrescine D-glucose D-glucose D-glucose D-glucose guanine xanthosine myo-inositol/ ABC polyamine glucose glucose hexose glucose nucleobase proton transporter transporter transporter transporter transporter transporter transporter AAP3 AAP3 NT2 symporter (ABCG4) (POT1) (GT3) (GT1) (GT4) (GT2) (NT3) (MIT) 1-alkyl-2-acyl-phosphatidylcholine inosine arg arg a phosphatidylcholine spermidine D-fructose D-fructose D-fructose D-fructose hypoxanthine guanosine putrescine myo-inositol D-galactose D-galactose D-mannose D-galactose xanthine xanthosine D-mannose D-mannose D-glucose D-mannose adenine D-glucose D-glucose D-glucose guanine Fatty Acid -

Exoribonuclease Xrn1 by Cofactor Dcs1 Is Essential for Mitochondrial Function in Yeast

Activation of 5′-3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1 by cofactor Dcs1 is essential for mitochondrial function in yeast Flore Sinturela,b, Dominique Bréchemier-Baeyb, Megerditch Kiledjianc, Ciarán Condonb, and Lionel Bénarda,b,1 aLaboratoire de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire des Eucaryotes, Institut de Biologie Physico-Chimique, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Formation de Recherche en Evolution (FRE) 3354, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, 75005 Paris, France; bLaboratoire de l’Expression Génétique Microbienne, Institut de Biologie Physico-Chimique, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Propre de Recherche 9073, Université de Paris 7-Denis-Diderot, 75005 Paris, France; and cDepartment of Cell Biology and Neuroscience, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854 Edited* by Reed B. Wickner, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved April 6, 2012 (received for review December 6, 2011) The scavenger decapping enzyme Dcs1 has been shown to facilitate Saccharomyces cerevisiae (16). Known regulatory RNAs belong to the activity of the cytoplasmic 5′-3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1 in eukar- this class, and their stabilization in the absence of Xrn1 could yotes. Dcs1 has also been shown to be required for growth in glyc- explain the aberrant expression of some genes. erol medium. We therefore wondered whether the capacity to Few studies have investigated how the activity of exoribonu- activate RNA degradation could account for its requirement for cleases is modulated in connection to cell physiology (17, 18). growth on this carbon source. Indeed, a catalytic mutant of Xrn1 Here, we focus on Dcs1, a factor that potentially controls the is also unable to grow in glycerol medium, and removal of the activity of the exoribonuclease Xrn1 (4).