Degradation of Unmethylated Mirna/Mirna S by a Deddy-Type 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanisms of Salmonella Attachment and Survival on In-Shell Black Peppercorns, Almonds, and Hazelnuts

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Mechanisms of Salmonella Attachment and Survival on In-Shell Black Peppercorns, Almonds, and Hazelnuts. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5534264q Authors Li, Ye Salazar, Joelle K He, Yingshu et al. Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.3389/fmicb.2020.582202 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California fmicb-11-582202 October 19, 2020 Time: 10:46 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 23 October 2020 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.582202 Mechanisms of Salmonella Attachment and Survival on In-Shell Black Peppercorns, Almonds, and Hazelnuts Ye Li1, Joelle K. Salazar2, Yingshu He1, Prerak Desai3, Steffen Porwollik3, Weiping Chu3, Palma-Salgado Sindy Paola4, Mary Lou Tortorello2, Oscar Juarez5, Hao Feng4, Michael McClelland3* and Wei Zhang1* 1 Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Illinois Institute of Technology, Bedford Park, IL, United States, 2 Division of Food Processing Science and Technology, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Bedford Park, IL, United States, 3 Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States, 4 Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 5 Department Edited by: of Biology, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL, United States Chrysoula C. Tassou, Institute of Technology of Agricultural Products, Hellenic Agricultural Salmonella enterica subspecies I (ssp 1) is the leading cause of hospitalizations and Organization, Greece deaths due to known bacterial foodborne pathogens in the United States and is Reviewed by: frequently implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks associated with spices and nuts. -

Exoribonuclease Nibbler Shapes the 3″ Ends of Micrornas

Current Biology 21, 1878–1887, November 22, 2011 ª2011 Elsevier Ltd All rights reserved DOI 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.034 Article The 30-to-50 Exoribonuclease Nibbler Shapes the 30 Ends of MicroRNAs Bound to Drosophila Argonaute1 Bo W. Han,1 Jui-Hung Hung,2 Zhiping Weng,2 precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) [8]. Pre-miRNAs comprise Phillip D. Zamore,1,* and Stefan L. Ameres1,* a single-stranded loop and a partially base-paired stem whose 1Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department of termini bear the hallmarks of RNase III processing: a two-nucle- Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology otide 30 overhang, a 50 phosphate, and a 30 hydroxyl group. 2Program in Bioinformatics and Integrative Biology Nuclear pre-miRNAs are exported by Exportin 5 to the cyto- University of Massachusetts Medical School, plasm, where the RNase III enzyme Dicer liberates w22 nt 364 Plantation Street, Worcester, MA 01605, USA mature miRNA/miRNA* duplexes from the pre-miRNA stem [9–12]. Like all Dicer products, miRNA duplexes contain two- nucleotide 30 overhangs, 50 phosphate, and 30 hydroxyl groups. Summary In flies, Dicer-1 cleaves pre-miRNAs to miRNAs, whereas Dicer-2 converts long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into Background: MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are w22 nucleotide (nt) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which direct RNA interference small RNAs that control development, physiology, and pathol- (RNAi), a distinct small RNA silencing pathway required for ogy in animals and plants. Production of miRNAs involves the host defense against viral infection and somatic transposon sequential processing of primary hairpin-containing RNA poly- mobilization, as well as gene silencing triggered by exogenous merase II transcripts by the RNase III enzymes Drosha in the dsRNA [13, 14]. -

Human Catechol O-Methyltransferase Genetic Variation

Molecular Psychiatry (2004) 9, 151–160 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1359-4184/04 $25.00 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Human catechol O-methyltransferase genetic variation: gene resequencing and functional characterization of variant allozymes AJ Shield1, BA Thomae1, BW Eckloff2, ED Wieben2 and RM Weinshilboum1 1Department of Molecular Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Mayo Medical School, Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN, USA; 2Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Mayo Medical School, Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN, USA Catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT) plays an important role in the metabolism of catecholamines, catecholestrogens and catechol drugs. A common COMT G472A genetic polymorphism (Val108/158Met) that was identified previously is associated with decreased levels of enzyme activity and has been implicated as a possible risk factor for neuropsychiatric disease. We set out to ‘resequence’ the human COMT gene using DNA samples from 60 African-American and 60 Caucasian-American subjects. A total of 23 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), including a novel nonsynonymous cSNP present only in DNA from African-American subjects, and one insertion/deletion were observed. The wild type (WT) and two variant allozymes, Thr52 and Met108, were transiently expressed in COS-1 and HEK293 cells. There was no significant change in level of COMT activity for the Thr52 variant allozyme, but there was a 40% decrease in the level of activity in cells transfected with the Met108 construct. Apparent Km values of the WT and variant allozymes for the two reaction cosubstrates differed slightly, but significantly, for 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid but not for S-adenosyl-L-methionine. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

Characterization of the Mammalian RNA Exonuclease 5/NEF-Sp As a Testis-Specific Nuclear 3′′′′′ → 5′′′′′ Exoribonuclease

Downloaded from rnajournal.cshlp.org on October 7, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Characterization of the mammalian RNA exonuclease 5/NEF-sp as a testis-specific nuclear 3′′′′′ → 5′′′′′ exoribonuclease SARA SILVA,1,2 DAVID HOMOLKA,1 and RAMESH S. PILLAI1 1Department of Molecular Biology, University of Geneva, CH-1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland 2European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Grenoble Outstation, 38042, France ABSTRACT Ribonucleases catalyze maturation of functional RNAs or mediate degradation of cellular transcripts, activities that are critical for gene expression control. Here we identify a previously uncharacterized mammalian nuclease family member NEF-sp (RNA exonuclease 5 [REXO5] or LOC81691) as a testis-specific factor. Recombinant human NEF-sp demonstrates a divalent metal ion-dependent 3′′′′′ → 5′′′′′ exoribonuclease activity. This activity is specific to single-stranded RNA substrates and is independent of their length. The presence of a 2′′′′′-O-methyl modification at the 3′′′′′ end of the RNA substrate is inhibitory. Ectopically expressed NEF-sp localizes to the nucleolar/nuclear compartment in mammalian cell cultures and this is dependent on an amino-terminal nuclear localization signal. Finally, mice lacking NEF-sp are viable and display normal fertility, likely indicating overlapping functions with other nucleases. Taken together, our study provides the first biochemical and genetic exploration of the role of the NEF-sp exoribonuclease in the mammalian genome. Keywords: NEF-sp; LOC81691; Q96IC2; REXON; RNA exonuclease 5; REXO5; 2610020H08Rik INTRODUCTION clease-mediated processing to create their final 3′ ends: poly(A) tails of most mRNAs or the hairpin structure of Spermatogenesis is the process by which sperm cells are replication-dependent histone mRNAs (Colgan and Manley produced in the male germline. -

The Microbiota-Produced N-Formyl Peptide Fmlf Promotes Obesity-Induced Glucose

Page 1 of 230 Diabetes Title: The microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide fMLF promotes obesity-induced glucose intolerance Joshua Wollam1, Matthew Riopel1, Yong-Jiang Xu1,2, Andrew M. F. Johnson1, Jachelle M. Ofrecio1, Wei Ying1, Dalila El Ouarrat1, Luisa S. Chan3, Andrew W. Han3, Nadir A. Mahmood3, Caitlin N. Ryan3, Yun Sok Lee1, Jeramie D. Watrous1,2, Mahendra D. Chordia4, Dongfeng Pan4, Mohit Jain1,2, Jerrold M. Olefsky1 * Affiliations: 1 Division of Endocrinology & Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 2 Department of Pharmacology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 3 Second Genome, Inc., South San Francisco, California, USA. 4 Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. * Correspondence to: 858-534-2230, [email protected] Word Count: 4749 Figures: 6 Supplemental Figures: 11 Supplemental Tables: 5 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 22, 2019 Diabetes Page 2 of 230 ABSTRACT The composition of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota and associated metabolites changes dramatically with diet and the development of obesity. Although many correlations have been described, specific mechanistic links between these changes and glucose homeostasis remain to be defined. Here we show that blood and intestinal levels of the microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide, formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF), are elevated in high fat diet (HFD)- induced obese mice. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the N-formyl peptide receptor Fpr1 leads to increased insulin levels and improved glucose tolerance, dependent upon glucagon- like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Obese Fpr1-knockout (Fpr1-KO) mice also display an altered microbiome, exemplifying the dynamic relationship between host metabolism and microbiota. -

EZH2 in Normal Hematopoiesis and Hematological Malignancies

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 7, No. 3 EZH2 in normal hematopoiesis and hematological malignancies Laurie Herviou2, Giacomo Cavalli2, Guillaume Cartron3,4, Bernard Klein1,2,3 and Jérôme Moreaux1,2,3 1 Department of Biological Hematology, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier, France 2 Institute of Human Genetics, CNRS UPR1142, Montpellier, France 3 University of Montpellier 1, UFR de Médecine, Montpellier, France 4 Department of Clinical Hematology, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier, France Correspondence to: Jérôme Moreaux, email: [email protected] Keywords: hematological malignancies, EZH2, Polycomb complex, therapeutic target Received: August 07, 2015 Accepted: October 14, 2015 Published: October 20, 2015 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb repressive complex 2, inhibits gene expression through methylation on lysine 27 of histone H3. EZH2 regulates normal hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. EZH2 also controls normal B cell differentiation. EZH2 deregulation has been described in many cancer types including hematological malignancies. Specific small molecules have been recently developed to exploit the oncogenic addiction of tumor cells to EZH2. Their therapeutic potential is currently under evaluation. This review summarizes the roles of EZH2 in normal and pathologic hematological processes and recent advances in the development of EZH2 inhibitors for the personalized treatment of patients with hematological malignancies. PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF EZH2 state through tri-methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) [6]. -

BRCA1 Binds TERRA RNA and Suppresses R-Loop-Based Telomeric DNA Damage ✉ Jekaterina Vohhodina 1,2 , Liana J

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23716-6 OPEN BRCA1 binds TERRA RNA and suppresses R-Loop-based telomeric DNA damage ✉ Jekaterina Vohhodina 1,2 , Liana J. Goehring1, Ben Liu1,2, Qing Kong1,2, Vladimir V. Botchkarev Jr.1,2, Mai Huynh1, Zhiqi Liu1, Fieda O. Abderazzaq1,2, Allison P. Clark1,2, Scott B. Ficarro1,3,4,5, Jarrod A. Marto 1,3,4,5, ✉ Elodie Hatchi 1,2 & David M. Livingston 1,2 R-loop structures act as modulators of physiological processes such as transcription termi- 1234567890():,; nation, gene regulation, and DNA repair. However, they can cause transcription-replication conflicts and give rise to genomic instability, particularly at telomeres, which are prone to forming DNA secondary structures. Here, we demonstrate that BRCA1 binds TERRA RNA, directly and physically via its N-terminal nuclear localization sequence, as well as telomere- specific shelterin proteins in an R-loop-, and a cell cycle-dependent manner. R-loop-driven BRCA1 binding to CpG-rich TERRA promoters represses TERRA transcription, prevents TERRA R-loop-associated damage, and promotes its repair, likely in association with SETX and XRN2. BRCA1 depletion upregulates TERRA expression, leading to overly abundant TERRA R-loops, telomeric replication stress, and signs of telomeric aberrancy. Moreover, BRCA1 mutations within the TERRA-binding region lead to an excess of TERRA-associated R- loops and telomeric abnormalities. Thus, normal BRCA1/TERRA binding suppresses telomere-centered genome instability. 1 Department of Cancer Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA. 2 Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. 3 Blais Proteomics Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA. -

Role for Cytoplasmic Nucleotide Hydrolysis in Hepatic Function and Protein Synthesis

Role for cytoplasmic nucleotide hydrolysis in hepatic function and protein synthesis Benjamin H. Hudson1, Joshua P. Frederick1, Li Yin Drake, Louis C. Megosh, Ryan P. Irving, and John D. York2,3 Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710 Edited by David W. Russell, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, and approved February 11, 2013 (received for review March 26, 2012) Nucleotide hydrolysis is essential for many aspects of cellular (5–7), which is degraded to 5′-AMP by a family of enzymes known function. In the case of 3′,5′-bisphosphorylated nucleotides, mam- as 3′-nucleotidases (8). mals possess two related 3′-nucleotidases, Golgi-resident 3′-phos- Mammalian genomes encode two 3′-nucleotidases, the recently phoadenosine 5′-phosphate (PAP) phosphatase (gPAPP) and characterized Golgi-resident PAP phosphatase (gPAPP) and Bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase 1 (Bpnt1). gPAPP and Bpnt1 localize Bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase 1 (Bpnt1), which localize to the to distinct subcellular compartments and are members of a con- Golgi lumen and cytoplasm, respectively (Fig. 1B)(8–11). gPAPP served family of metal-dependent lithium-sensitive enzymes. Al- and Bpnt1 are members of a family of small-molecule phospha- though recent studies have demonstrated the importance of tases whose activities are both dependent on divalent cations and gPAPP for proper skeletal development in mice and humans, the inhibited by lithium (8). The family comprises seven mammalian role of Bpnt1 in mammals remains largely unknown. Here we re- gene products: fructose bisphosphatase 1 and 2, inositol monophos- port that mice deficient for Bpnt1 do not exhibit skeletal defects phatase 1 and 2, inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase, gPAPP, but instead develop severe liver pathologies, including hypopro- and Bpnt1 (Fig. -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

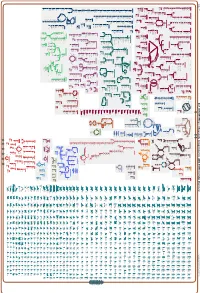

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Ron Caspi Peter Midford Peter D Karp An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_003855395Cyc: Shewanella livingstonensis LMG 19866 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. -

The Importance of Study Design Abundant Features in High

The importance of study design for detecting differentially abundant features in high -throughput experiments Luo Huaien 1* , Li Juntao 1*, C hia Kuan Hui Burton 1, Paul Robson 2, Niranjan Nagarajan 1# a b c d Supplementary Figure 1. Variability in performance across DATs with few repreplicates.licates. The subfigures depict precision-recall tradeoffs for DATs, under a range of experimexperimenentaltal conditions and with few replicates (2 in this case). The following parameters were used in EDDA for the sub figures: (a) PDA=30% and FC=Uniform[2,6] (b) as in subfigure (a) but with AP=HBR (c) PDA= [15% UP, 30% DOWN] and FC=Uniform[3,15] (d) PDA=[50% UP, 25% DOWN], FC=Normal[5,1.33] and SM=Full. Common parameters unless otherwise stated include AP=BP, EC=1000, ND=500 per entity, SM=NB and SV=0.5. a b c d Supplementary Figure 2 . Variability in performance across DATs with few data -points. Note that as in Supplementary Figure 1 , the performance of DATs varies widely merely by changing the number of replicates from 1 to 4 in sub figures (a)-(d) in a situation where the number data -points generated is limited (only 50 on average per entity). Results reported are based on data generated in EDDA with the following parameters (roughly mimicking a microbial RNA-seq application) : EC=1000, PDA=26%, FC=Uniform[3,7 ], AP=BP, SM=Full and SV=0.85. Supplementary Figure 3. Distribution of relative abundance in different empirically derived profiles. Note that both axes are plotted on a log-scale and that while BP does not have entities with relative abundance < 1e-5, the profile from Wu et al is more enriched for entities with relative abundance < 1e-5 than the HBR profile. -

Expanding the Structural Diversity of DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors

pharmaceuticals Article Expanding the Structural Diversity of DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors K. Eurídice Juárez-Mercado 1 , Fernando D. Prieto-Martínez 1 , Norberto Sánchez-Cruz 1 , Andrea Peña-Castillo 1, Diego Prada-Gracia 2 and José L. Medina-Franco 1,* 1 DIFACQUIM Research Group, Department of Pharmacy, School of Chemistry, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Avenida Universidad 3000, Mexico City 04510, Mexico; [email protected] (K.E.J.-M.); [email protected] (F.D.P.-M.); [email protected] (N.S.-C.); [email protected] (A.P.-C.) 2 Research Unit on Computational Biology and Drug Design, Children’s Hospital of Mexico Federico Gomez, Mexico City 06720, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are attractive compounds for epigenetic drug discovery. They are also chemical tools to understand the biochemistry of epigenetic processes. Herein, we report five distinct inhibitors of DNMT1 characterized in enzymatic inhibition assays that did not show activity with DNMT3B. It was concluded that the dietary component theaflavin is an inhibitor of DNMT1. Two additional novel inhibitors of DNMT1 are the approved drugs glyburide and panobinostat. The DNMT1 enzymatic inhibitory activity of panobinostat, a known pan inhibitor of histone deacetylases, agrees with experimental reports of its ability to reduce DNMT1 activity in liver cancer cell lines. Molecular docking of the active compounds with DNMT1, and re-scoring with the recently developed extended connectivity interaction features approach, led to an excellent agreement between the experimental IC50 values and docking scores. Citation: Juárez-Mercado, K.E.; Keywords: dietary component; epigenetics; enzyme inhibition; focused library; epi-informatics; Prieto-Martínez, F.D.; Sánchez-Cruz, multitarget epigenetic agent; natural products; chemoinformatics N.; Peña-Castillo, A.; Prada-Gracia, D.; Medina-Franco, J.L.