Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BVDC @ BCHP Pleasure Driving Show

www.bvdc.org July 2013 Newsletter for the BVDC, Inc. Serving the Driving Enthusiast BVDC @ BCHP Pleasure Driving Show Jessica Nogradi and her mini at the Bucks County Horse Park Pleasure Driving Show in June - Photo by Debbie Wolf Inside this Issue: BVDC Pleasure Driving Schooling Show - 7/28 BVDC Board Meeting BVDC Cones Clinic Summer Series w/ Suzy Stafford July 9, 2013 at 7:00 PM BVDC Fun Day at Eden Valley Farm - 8/17 New Bolton Center BVDC Pleasure Drive at Thunder Ridge Farm - 10/20 BVDC Novice Driver Clinic article & pictures All Members Welcome BVDC Member Results at Local Competitions Info: Debby Donovan 856-981-1868 or Info on upcoming Mid-Atlantic driving shows [email protected] BVDC Pleasure Driving Schooling Show Sunday, July 28th 9:00 AM Buxmont Riding Club Showgrounds, PA 71 Clump Road, Tylersport, PA 18971 www.buxmontridingclub.com Divisions: Horse, Pony, VSE, Novice Horse, Novice Driver, Junior Division classes: Working, Reinsmanship, Cones, Scurry Other classes: Gambler’s Choice, Double Jeopardy, Grooms Class Judge: Rebecca Merritt This will be a low-key fun show (hat, gloves, and apron, but jackets not required; no turnout classes) providing all levels of horse and driver an opportunity to school in a relaxed atmosphere. Open to non-members. Prize list can be downloaded from the BVDC website from the “Upcoming Shows and Competitions” tab or at this link: http://bvdc.shutterfly.com/upcomingshowsandcompetitions This is not an American Driving Society Recognized Driving Show, however we will follow the ADS Rules, which can be found at this website: http://www.americandrivingsociety.org/ADS_Rulebook.asp Fees: If received by 7/26: $10 per class for BVDC members; $13 per class for non- members; $15 per class for show day entries. -

SCHEDULE Online: Box Office: 0844 581 8282 Calls Cost 7P Per Minute Plus Your Phone Company’S Access Charge Hospitality: 02476 858 205

HORSE OF THE YEAR SHOW 2nd-6th October 2019 NEC BIRMINGHAM ate celebra ltim tion e u the horse o Th f SCHEDULE Online: www.hoys.co.uk Box Office: 0844 581 8282 Calls cost 7p per minute plus your phone company’s access charge Hospitality: 02476 858 205 British RAISING THE BAR 9389 HOYS19 A5 Schedule Cover with Spine.indd 1 20/06/2019 09:26 2 Ibis Styles | Hotel 2019 Show oftheYear Horse Train NEC Station Piazza HORSE OF THE YEAR SHOW 2019 Shuttle Bus Stop Collecting Ring Arena The Main Retail Entrance Village GATE 1 West Car KEY Park Pedestrian Access Point Pedestrian Route Collecting Ring Hilton Metropole Route for Public Cars Hotel Route for Horse Boxes To Airport Horse Walk International Competitor Areas Arena Public Areas Rider’s A45 Area Stable Area/Lorry Park Birmingham Toilet T Competitor Shower S Service Area Genting Vets T Hotel Crowne Plaza S Stable East Car M6 Manager Park M1 Show Jumping & Passes GATE 2 Declarations Office Equestrian Office Catering Unit T International M42 Stables T Outdoor Exercise Stables & Arena Lorry Park T Arden Hotel & Leisure Club A45 M42 Coventry M40 JUNCTION 6 Event Director Emma Williams With Best Wishes, make some wonderful memories beto cherished for yearsto come. being enjoy hope Ltd we Media you that behalf you that of Grandstand On and part of our aShow October. asuccessful Show andwe look forward welcomingto youto ‘The Ultimate Celebrationof theHorse’ in Congratulations all to horses. own their totry with ideas helpful some home take am sure that our visitorsas well asour younger competitorswill find it incredibly insightful andbe able to Olli, as well as aguest appearance from com withtheir two well along and byFletcher Tina will be Graham hosted which timetable Wednesday’s into Masterclass Showjumping a introduced 2019,have we New for Masterclass. -

Steinbeck, John ''The Pearl''-Xx-En-Sp-Sp.Pdf

J. Steinbeck’s Pearl tr. de H. Vázquez Rial tr. de F. Baldiz The Pearl [1945] LA PERLA LA PERLA by de de 5 John Steinbeck JOHN STEINBECK John Steinbeck tr. de Horacio Vázquez Rial Arrow Books, Libro digitalizado por www.pidetulibro.cjb.net 10 London, 1995 Edhasa, Barcelona, 2002 [esta Web utiliza la insólita traducción subguiente de Francisco Baldiz publicada por Caralt en 1948, 1975, 1987, etc.] 15 ‘In the town they tell the story of the great pearl «En el pueblo se cuenta la historia de la gran perla, how it was found and how it was lost again. They de cómo fue encontrada y de cómo volvió a perderse. Se tell of Kino, the fisherman, and of his wife, Juana, habla de Kino, el pescador, y de su esposa, Juana, y del and of the baby; Coyotito. And because the story bebé, Coyotito. Y como la historia ha sido contada tan a 20 has been told so often, it has taken root in every menudo, ha echado raíces en la mente de todos. Y como man’s mind. And, as with all retold tales that are todas las historias que se narran muchas veces y que es- in people’s hearts, there are only good and bad tán en los corazones de las gentes, sólo tiene cosas bue- things and black and white things and good and nas y malas, y cosas negras y blancas, y cosas virtuosas evil things and no in-between anywhere. y malignas, y nada intermedio. 25 parable: a fable or story of something which might ‘If this story is a parable, perhaps »Si esta historia es una parábola, tal vez have happened, told to illustrate a particular way of looking at the world everyone takes his own meaning from it and cada uno le atribuya un sentido particular y lea reads his own life into it. -

Equine Prize Schedule

EQuInE prIzE scHeDuLe NeW FoR 2020 Light Horses • Concours d’Elegance Ridden & In Hand Class Heavy Horses • All In Harness Classes (Wednesday only) Private Driving • Mountain & Moorland Class Showjumping • Junior Academy Inter County Team Competition Scurry • Large, Small and Championship (Wednesday only) EQuInE enTrIeS clOsE 17 APrIl 2020 SHoWjUmPiNg ENtRiEs cLoSe 29 maY 2020 Equine Prize Schedules 2020 Cover.indd 1 12/02/2020 09:13:37 The Royal Norfolk Show Equestrian Village Map Farrier Competition EQUINE PARKING Private Driving Collecting/ Warm-up Ring STABLES Livestock timetables for print 2019.indd 1 14/02/2019 12:04:54 EQUINE PRIZE SCHEDULE THE ROYAL NORFOLK SHOW 2020 Wednesday 1 & Thursday 2 July Patron: Her Majesty the Queen ______________________________________________________________ HEAVY & LIGHT HORSES PRIVATE DRIVING SCURRY & SHOWJUMPING FARRIER COMPETITION ______________________________________________________________ Equine entries close - Friday 17 April Showjumping entries close - Friday 29 May ** MAKE YOUR ENTRIES ONLINE ** Enter online at: royalnorfolkshow.co.uk ______________________________________________________________ Equine Co-ordinator: Maria Skitmore T: 01603 731 963 - E: [email protected] ROYAL NORFOLK AGRICULTURAL ASSOCIATION Norfolk Showground, Dereham Road, Norwich. NR5 0TT Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England No 1817702. Registered Charity 289581. THE ROYAL NORFOLK SHOW 2020 - TIMETABLE, WEDNESDAY 1 JULY Time Grand Ring Light Horse Ring Wensum Ring Glaven Ring Ring 22 Waveney -

DHS 2011 Prize List.Pdf

34E>=35,=(/,67 'HYRQ+RUVH6KRZDQG &RXQWU\)DLU 'HYRQ3$ 7KXUVGD\0D\WKURXJK6XQGD\-XQH 3UHVHQWHGE\:HOOV)DUJR IRUWKHEHQH¿WRI7KH%U\Q0DZU+RVSLWDO (QWULHV&ORVH $SULO $$+XQWHUV :KHUH&KDPSLRQV0HHW 86() -XPSHUV 1DWLRQDO6KRZ+XQWHU +DOORI)DPH+RQRU6KRZ DEVON HORSE SHOW AND COUNTRY FAIR, INC. RULES AND REGULATIONS EVERY CLASS OFFERED HEREIN WHICH IS COVERED BY THE RULES AND SPECIFICATIONS OF THE CURRENT USEF RULE BOOK WILL BE CONDUCTED AND JUDGED IN ACCORDANCE THEREWITH. TIME SCHEDULE: The time schedule and order of events herein is tentative. The white booklet (available at the show office) will contain the official starting times, changes in scheduling and revisions. EXHIBITORS ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR HAVING ENTRIES AT THE RING 30 MINUTES BEFORE CLASS TIME. NO CLASS WILL BE DELAYED MORE THAN 3 MINUTES. EXHIBITORS MUST REQUEST PADDOCK MASTER TO ADJUST FOR CONFLICTS. ENTRIES: Entries for Hunter, Equitation and Jumper Sections close Monday, April 4, 2011. Entries postmarked after midnight, Monday, April 4, 2011 will not be accepted, unless otherwise noted. Entries for Saddlebred, Hackney, Harness, Roadster, Coaching, Driving, Pleasure Drive and Friesians close on Monday, April 25, 2011. Post entries will not be accepted unless otherwise noted. NO "BLANK CHECKS" ACCEPTED - they will be filled in for proper amount. All entries will be charged a $50.00 (non-refundable/non- transferable) Office Fee. Late entries in the hunter and jumper divisions will be placed below all entries received by the close of entires. No faxed entries will be accepted. Entries with postage meter date and postmark: Where an entry is received by mail bearing a postage meter date as well as a postmark by the post office department, the post office date will be considered the effective date of mailing. -

Pony Championships Catton Hall, Derbyshire, UK 13 – 17 July 2005

FEI World Combined Pony Championships Catton Hall, Derbyshire, UK 13 – 17 July 2005 The British Team www.horsedrivingtrials.co.uk Introduction Whether you are a newcomer to Carriage Driving or a seasoned campaigner, I would like to introduce you to the British Team for the second ever FEI World Combined Pony Championships, which we are pleased to host in Britain from 13 – 17 July 2005. 12 months of competitive selection and many years of training have gone into preparing for these Championships.The dedication and SINGLE tenacity, not only of the whole team, but also of their many supporters, grooms, PONIES helpers and friends can easily pass unnoticed.We are a small sport, a friendly sport Sara Howe and a tightly knit community.The fund raising has been hard and the preparations Sue Denney arduous. It falls to me to thank personally all those, individuals and companies, who have contributed in many different ways.This I do from the bottom of my being. To give this outstanding sport the recognition that it truly deserves, and to ensure that it continues to grow, we must continue to evolve our ideas and strategies.The way that this group of people has come together to share ideas, train together and help each other to achieve their best is an example of how to build for the future. I know that they will all perform to their highest standards and beyond. I am sure that we will be proud of them.We all wish them every success for these World Championships. PAIRS OF PONIES Jo Rennison Rachel Stevens The Earl of Onslow Chairman, BHDTA For further -

1 Thursday 29Th August 2019 Equinational Photography

THURSDAY 29TH AUGUST 2019 DEEPING CARAVAN RING – IN HAND RING RING TWO – IN HAND RING 8.00am 8.00am Judge: Mr C McCormick Judge: Mrs J Carter Class 1 In Hand Best Conditioned M&M Class 17 In Hand Riding Pony 1,2,3 years 8.45am Class 18 In Hand Riding Pony 4 years & over Judge: Mr M Chadwick CHAMPIONSHIP Class 2 In Hand Best Condition 1,2,3 years 8.45am Class 3 In Hand Best Condition 4 years & over Judge: Mrs J Carter CHAMPIONSHIP Class 19 In Hand Hunter Pony 1,2,3 years 9.45am Class 20 In Hand Hunter Pony 4 years & over Judge: Mr C McCormick CHAMPIONSHIP Class 4 Best M&M Amateur Handler 9.30am 10.15am Judge: Mrs P Potter Judge: Mr C McCormick Class 21 Young Handlers 13-18 years Class 5 Amateur Highlands In Hand 4 years + Class 22 Young Handlers 9-12 years Class 6 Amateur Dales / Fell In Hand 4 years + Class 23 Young Handlers 8 years & under Class 7 Amateur NF / Conn In Hand 4 years + CHAMPIONSHIP Class 8 Amateur Shetlands In Hand 4 years + 11.15am Class 9 Amateur Dart/Exmoor In Hand 4 years + Judge: Mrs S Palmer Class 10 Amateur Welsh A In Hand 4yrs + Class 24 In Hand Veteran Pony Class 11 Amateur Welsh B In Hand 4yrs + Class 25 In Hand Veteran Horse Class 12 Amateur Welsh C/D In Hand 4 years + CHAMPIONSHIP Not before 2.00pm 12.15pm Judge: Ms P Ryan Judge: Mrs C Merrigan-Martin Class 13 Amateur M&M In Hand Small Brds Y’ling BSPA PIEBALD/SKEWBALD IN HAND CHAMP Class 14 Amateur M&M In Hand Small Brds 2-3 yrs Class 800 Pie/Skew Horse 1,2,3 years old Class 15 Amateur M&M In Hand Large Brds Y’ling Class 801 Pie/Skew Pony 1,2,3, years old Class -

® TOYOTA Proud Sponsor IW I

TEXAS PARKS & WILDLIFE REG LAM ENTOS DE GAZA Y PESCA t Ic~y : 1a ® TOYOTA Proud Sponsor IW I Buy an Annual Public Hunting Permit Nearly one million acres of walk-in hunting opportunities for dove, deer, turkey, quail, waterfowl, feral hog and much more. Youth under 17 can accompany a permitted adult for free. Only $48 - available online or wherever hunting or fishing licenses are sold. Buy Al yours starting August 15. Also, Apply for Drawn Hunts )- . Hunt desert bighorn sheep, pronghorn, i, mule deer, white-tailed deer, exotics, turkey, JIIRLg alligator and more. ' Youth-Only hunt opportunities also available. S EXA Apply online now! Find high-quality hunts . M across Texas. ARKS s';" . ' _ . ' , _ - . 1_4LD: " u F. 2016 TPWD PWD BK K0700-1679 18/16) CALENDARIO CINEGETICO 2016-2017 Ademis de la licencia de caza se requiere un sello de endoso ($7) para cazar ayes migratorias, incluyendo la paloma huilota (se requiere el permiso "Federal Sandhill Crane" para cazar grulla gris). Para cazar pavo, codorniz, faisAn o chachalaca, se requiere el sello de endoso "Upland Game Bird Stamp" ($7). Consulte la seccidn de "Listados por condado" para reglamentos especificos. LAGARTO (ALIGATOR) 22 condados y propiedades especiales (solo con permiso) 10-30 sept. Resto del estado 1 abril - 30 junio BERRENDO (ver p.76) 1-9 oct. PALOMA (favor de reportar anillos de identificacion al reportband.gov) Zona del norte 1 sept. - 13 nov. y 17 dic. - 1 enero Zona central 1 sept. -6 nov. y 17 dic. -8 enero Zona del sur 23 sept. - 13 nov. y 17 dic.- 23 enero Zona especial para paloma ala blanca 3-4 y 10-11 sept.; 23 sept. -

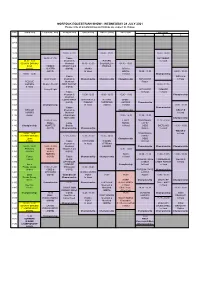

NORFOLK EQUESTRIAN SHOW - WEDNESDAY 28 JULY 2021 Please Note All Programming and Timings Are Subject to Change

NORFOLK EQUESTRIAN SHOW - WEDNESDAY 28 JULY 2021 Please note all programming and timings are subject to change Time Grand Ring Light Horse Ring Wensum Ring Glaven Ring Waveney Ring Ivan Cooke Cattle Rings A B C 0730 0745 0800 0815 08.00 - 12.00 08.00 - 10.00 08.00 - 09.30 0830 08.15 - 11.15 Ridden DARTMOOR 08.30 - 9.00 Mountain & RIDDEN In Hand 0845 SCURRY DRIVING Moorland 08.30 - 10.00 SKEWBALD & 08.30 - 10.00 Small RIDDEN WELSH C & D PIEBALD 0900 (HOYS) HUNTER (HOYS) ARABS RIDING (HOYS) In Hand HORSE 09.00 - 11.00 09.00 - 10.30 0915 09.00 - 12.00 In Hand Championship Ridden WELSH A 0930 Light Weight Mountain & Championship Championship Championship HAFLINGER In Hand RESCUE Moorland Ridden 0945 HORSES Medium Weight NEW FOREST 09.30 - 11.15 In Hand (HOYS) 1000 Heavy Weight HAFLINGER EXMOOR Ridden In Hand In Hand 1015 Mountain & 10.00- 12.00 10.00 - 12.00 10.00 - 11.00 Championship Moorland 1030 CONNEMARA SKEWBALD & RIDDEN SPORT (HOYS) PIEBALD PARTBRED HORSES Championship 1045 Championship In Hand (HOYS) In Hand 10.30 - 11.30 Ridden Championship 1100 RESCUE Mountain & Championship WELSH B HORSES Moorland In Hand 1115 Ridden DALES/FELL 11.00 - 12.30 11.00 - 13.00 HIGHLAND Championship 1130 11.15 - 12.30 LIGHT TRADITIONAL 11.15 - 13.00 SMALL Large HORSE GYPSY 1145 Championship HUNTERS Breeds In Hand COBS SHETLAND 11.30 - 13.00 (HOYS) Championship Championship Ridden In Hand 1200 WELSH C 12.00 - 12.30 TRADITIONAL In Hand 1215 SCURRY DRIVING 12.00 - 14.30 12.00 - 13.30 12.00 - 14.00 GYPSY Large Championship COBS 1230 (HOYS) Ridden PART BRED -

Capote, Truman ''Breakfast at Tiffany's''-Xx-En-Sp.P65

Capote’s Breakfast tr. de Enrique Murillo Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958) Desayuno en Tiffany’s by de 5 Truman Capote Truman Capote Random House, tr. de Enrique Murillo Inc. Nueva York, 1958 Anagrama, Barcelona, 1990 10 15 I am always drawn back to places Siempre me siento atraído por los lu- where I have lived, the houses and gares en donde he vivido, por las casas y their neighborhoods. For instance, los barrios. Por ejemplo, hay un edificio brownstone de arenisca roja there is a brownstone in the East de roja piedra arenisca en la zona de las 20 Seventies where, during the early Setenta Este donde, durante los primeros years of the war, I had my first New años de la guerra, tuve mi primer aparta- York apartment. It was one room mento neoyorquino. Era una sola habitación crowded with attic furniture, a sofa atestada de muebles de trastero, un sofá y and fat chairs upholstered in that unas obesas butacas tapizadas de ese espe- 25 itchy, particular red velvet that one cial y rasposo terciopelo rojo que solemos associates with hot days on a tram. asociar a los trenes en día caluroso. Tenía stucco plaster or cement used for coating wall surfaces The walls were stucco, and a color las paredes estucadas, de un color tirando a or moulding into architectural decorations. estuco 1. m. Masa de yeso blanco y agua de cola, con rather like tobacco-spit. Everywhere, esputo de tabaco mascado. Por todas partes, la cual se hacen y preparan muchos objetos que in the bathroom too, there were incluso en el baño, había grabados de ruinas después se doran o pintan. -

Light & Heavy Horses Private Driving Scurry

EQUINE SCHEDULE ___________________________________________________________________________________ LIGHT & HEAVY HORSES PRIVATE DRIVING SCURRY ENTRY CLOSING DATE - WEDNESDAY 30 JUNE 2021 ** ALL ENTRIES MUST BE MADE ONLINE ** Enter online at: royalnorfolkshow.co.uk ___________________________________________________________________________________ CONTACT: Equine Co-ordinator: Maria Skitmore T: 01603 731 963 - E: [email protected] ROYAL NORFOLK AGRICULTURAL ASSOCIATION Norfolk Showground, Dereham Road, Norwich. NR5 0TT GENERAL INFORMATION 1. SITE The Show will be held on the Norfolk Showground, New Costessey, Norwich, NR5 0TT 5 miles west of Norwich, just off the A47 Norwich Southern By-Pass at the A1074 junction (Longwater Interchange). Please use all appropriate entrances as signed off the main roads nearer to the Showground. 2. ARRIVAL AND DEPARTURE Exhibitors should arrive at the Showground in good time, making allowance for any possible traffic delays. Exhibitors may depart after their class has been judged. 3. ACCOMMODATION Exhibitors: A list of convenient Hotels, B&Bs, etc. can be found on the RNAA website. Stables: No stables will be available at this event. Catering: A variety of catering outlets will be operation on the day of the show only serving take away food and beverages for breakfast and lunch. 4. FINAL INSTRUCTIONS Full instructions will be issued to all exhibitors approximately 14 days prior to the Show. Admission passes will be based on 3 passes per equine. 5. ENTRIES Entry Fees are as stated beneath each Section Heading or at the front of the section. All entries MUST BE MADE ONLINE at www.rnaa.org.uk. Late entries will be accepted at the discretion of the Show and entries in all sections will be subject to space and availability. -

Schedule & Prize List

EQUINE SCHEDULE & PRIZE LIST 7, 8, 9 JUNE 2018 www.seas.org.uk 15513 SEAS Livestock & Equine Prize List covers A5 2018 v3.indd 2 12/12/2017 14:21 South of England Show 2018 Equine Prize List entry closing dates PAPER ONLINE Light and Heavy Horse Sunday 1 April Friday 13 April Showjumping Tuesday 1 May Friday 25 May PLEASE NOTE THAT LATE ENTRIES WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED Enter online: www.seas.org.uk/south-of-england-show Livestock and Events Executive: Elizabeth Crockford ([email protected]) South of England Showground, Ardingly, West Sussex, RH17 6TL T: 01444 892700 www.seas.org.uk 15513 SEAS Livestock & Equine Prize List covers A5 2018 v3.indd 4 12/12/2017 14:21 South of England Show 2018 Equine - Updates for 2018 Showjumping: We are holding three days of Showjumping in the Showing: Balcombe Ring - on the Saturday is the Petland Wood This year the Amateur Championship for Hacks, Riding Sussex Area 46 1.25m Open Final from the Qualifiers held Horses and Cobs along with Home Produced & or Local locally throughout the season at Pyecombe, Coomblands, classes for Hacks, Riding Horses and Cobs are all to be held Felbridge, Petley Wood and Crockstead. on Friday. The Amateur Championship has a first prize of £500 and a Reserve Champion prize of £250, 3rd £100, On Thursday we are running a HOYS Grade C qualifier 4th £75 and 5th £50 and we are also running an Area Trial. On Friday the International Stairway class and on Saturday an Accumulator class followed by Grand Prix all in the NEW CLASSES - Thursday: Light Horse Breeding Ardingly Arena - course builder - Bob Ellis.