The Baltimore Region Transit Governance and Funding Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY 2027 HART Transit Development Plan

Hillsborough Area Regional Transit (HART) Transit Development Plan 2018 - 2027 Major Update Final Report September 2017 Prepared for Prepared by HART | TDP i Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1-1 Objectives of the Plan ......................................................................................................................................... 1-1 State Requirements ............................................................................................................................................ 1-2 TDP Checklist ...................................................................................................................................................... 1-2 Organization of the Report .................................................................................................................................. 1-4 Section 2: Baseline Conditions ...................................................................................................................... 2-1 Study Area Description ....................................................................................................................................... 2-1 Population Trends and Characteristics ............................................................................................................. 2-3 Journey-to-Work Characteristics ....................................................................................................................... -

Bus/Light Rail Integration Lynx Blue Line Extension Reference Effective March 19, 2018

2/18 www.ridetransit.org 704-336-RIDE (7433) | 866-779-CATS (2287) 866-779-CATS | (7433) 704-336-RIDE BUS/LIGHT RAIL INTEGRATION LYNX BLUE LINE EXTENSION REFERENCE EFFECTIVE MARCH 19, 2018 INTEGRACIÓN AUTOBÚS/FERROCARRIL LIGERO REFERENCIA DE LA EXTENSIÓN DE LA LÍNEA LYNX BLUE EN VIGOR A PARTIR DEL 19 DE MARZO DE 2018 On March 19, 2018, CATS will be introducing several bus service improvements to coincide with the opening of the LYNX Blue Line Light Rail Extension. These improvements will assist you with direct connections and improved travel time. Please review the following maps and service descriptions to learn more. El 19 de marzo de 2018 CATS introducirá varias mejoras al servicio de autobuses que coincidirán con la apertura de la extensión de ferrocarril ligero de la línea LYNX Blue. Estas mejoras lo ayudarán con conexiones directas y un mejor tiempo de viaje. Consulte los siguientes mapas y descripciones de servicios para obtener más información. TABLE OF CONTENTS ÍNDICE Discontinued Bus Routes ....................................1 Rutas de autobús discontinuadas ......................1 54X University Research Park | 80X Concord Express 54X University Research Park | 80X Concord Express 201 Garden City | 204 LaSalle | 232 Grier Heights 201 Garden City | 204 LaSalle | 232 Grier Heights Service Improvements .........................................2 Mejoras al servicio ...............................................2 LYNX Blue Line | 3 The Plaza | 9 Central Ave LYNX Blue Line | 3 The Plaza | 9 Central Ave 11 North Tryon | 13 Nevin -

Corridor Revitalization Phase 2 Report

ROUTE 1 Introduction CORRIDOR REVITALIZATION STUDY Envisioning the Future PHASE 2 REPORT Improving Transportation July 12, 2002 Addressing Environmental Quality Fostering Community Well-Being PRESENTED BY Route 1 Corridor Task Force Howard County Department of Planning and Zoning Next Steps Table of Contents Introduction INTRODUCTION ...................................1 STUDY PURPOSE AND APPROACH ......................1 Study Phasing ................................1 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION .........................2 Citizen Workshops..............................2 PHASE 1 REPORT................................2 Promoting the Positive............................3 Transforming the Negative .........................3 Setting the Stage for Revitalization .....................3 Improving Transportation ..........................3 Enhancing Route 1 Appearance.......................3 Addressing the Needs of Youth .......................3 NORTH LAUREL CONCEPT PLAN .......................4 PHASE 2 REPORT ORGANIZATION ......................5 Envisioning the Future Phase 2 Report Topics ...........................5 ENVISIONING THE FUTURE.............................7 INTRODUCTION .................................7 CURRENT LAND USE PATTERN AND TRENDS ................7 Current Residential Land Use Patterns and Trends .............7 Current Commercial Land Use Patterns and Trends ............8 Current Industrial Land Use Patterns and Trends ..............8 LAND USE POLICIES ..............................9 Land Use Policy Goals ...........................9 -

3. Performance Measures

Airport Metro Connector Technical Refinement Study of Alternatives Phase I – AA/DEIS/DEIR Final 3. PERFORMANCE MEASURES The Technical Refinement Study utilizes performance measures similar to those presented in the 2012 AA Report. Table 3-1 summarizes the detailed performance measures for the following evaluation criteria: Passenger Convenience and Travel Time – Transfers and vertical changes inform an understanding of the quality of the Metro passenger experience. This is supplemented by an assessment of systemwide travel times, which strongly influence the overall attractiveness of transit compared to other modes. Environmental Factors – An initial environmental screening will identify the potential short-term construction impacts and long-term operational impacts associated with each alternative. Compatibility with Other Projects – Integration with future transit and airport plans is paramount in ensuring the project is compatible with future Metro and LAWA goals. Engineering/Physical Feasibility – The physical constructability of each alternative will be determined to ensure that the alternatives fit within acceptable parameters for utility and construction disruption, and airport constraints. Cost and Financial Feasibility – Capital construction costs for each alternative, which will include the construction of the guideway, stations, vehicles, and supporting facilities, determine the potential fiscal impacts of each alternative. As noted previously, the AMC project only has approximately $200 million allocated as part of Measure -

Written Testimony 12.216-4.20-17

Sayers, Margery From: Tina Bennett <[email protected]> Sent: Thursday, April 20, 2017 11:36 PM To: CounciIMail Subject: Public input on the proposed budget Greetings. If it is timely, I would like to express strong support for expenditure on bus stop improvement. I live near bus stops on Guilford Road and pass some on Broken Land Parkway. I see folks standing on grass or trying to keep feet dry by standing on a cement square (about 1 yard x 1 yard) if one is available. There is no shelter for many stops. At one on Guilford, folks will often sit on a pad-mount transformer because there is no other place to sit. There are no trash cans, so you can guess what is discarded on the ground. People look (and are) miserable at these stops, and such conditions do not encourage them to ride the buses. Howard County must meet basic needs (including safety) of riders to support bus ridership and support these people, many of whom might not be able to afford their own cars Thank you for your consideration. Respectfully, Tina Bennett and family _^ »S^»y ^ ^ Uniting East and West with a Bus, Bike, And BRIDGE ^ COLUMBIA Pedestrian Bridge ONE BRIDGE ONE COLUMBIA www.bridgecolumbia.org [email protected] April 13,2017 Dear Howard County Council Member, Friends of Bridge Columbia wholeheartedly supports the inclusion of funding for upgrades to the Route 29 pedestrian bridge (Budget Item B3863 FY2013 Downtown Columbia-Oakland Mills Connection Improvements). We appreciate the creativity of the county employees and contractors in generating the geodesic tube with spiral design and encourage you to support this project with the funding required to make it happen. -

Public Transportation Association

AMERICAN PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION ASSOCIATION 2017 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION FACT BOOK 2017 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION FACT BOOK 68th Edition March 2018 APTA’s Vision Statement Be the leading force in advancing public transportation. APTA’s Mission Statement APTA serves and leads its diverse membership through advocacy, innovation, and information sharing to strengthen and expand public transportation. Primary Author: MacPherson Hughes-Cromwick, Policy Analyst (202) 496-4812 [email protected] Data and Analysis: Matthew Dickens, Senior Policy Analyst (202) 496-4817 [email protected] American Public Transportation Association Paul P. Skoutelas, President and CEO APTA Policy Department Darnell C. Grisby, Director-Policy Development & Research Arthur L. Guzzetti, Vice President-Policy American Public Transportation Association 1300 I Street, NW, Suite 1200 East Washington, DC 20005 TELEPHONE: (202) 496-4800 E-MAIL: [email protected] www.apta.com Contents Overview of Public Transit Systems ....................................................................................................5 Total Number of Systems, Number of Modes Operated, 2015 Rail Openings Passenger Travel ................................................................................................................................7 Unlinked Passenger Trips by Mode, Unlinked Passenger Miles by Mode, Average Trip Length by Mode, VMT vs. Passenger Mile Growth, Population vs. Ridership Growth, ACS Transit Commuting Statistics Service Provided ............................................................................................................................. -

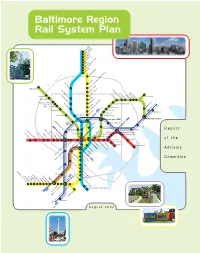

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

2030 Transit System Plan Refresh

2030 Transit System Plan Refresh Centers and Corridors Project Connect Growth Concept Map Joint use Task Force CRTPO Technical Coordinating Committee July 6, 2017 City of Charlotte The Origin Story Centers and Corridors Strategy developed in the 1990’s • Long-term growth management strategies for Charlotte- Mecklenburg • Five primary transportation and development corridors • Transform unfocused development patterns in corridors and wedges to compact mixed-use development along corridors and in station areas City of Charlotte 2025 Transit/Land Use Plan 2025 Transit / Land Use Plan . Vision for a long-term growth management strategy for Charlotte- Mecklenburg . Integrates rapid transit and mixed- used development along 5 transportation corridors . Expands transit system to serve between the rapid transit corridors . Provide more transportation choices to meet mobility needs . Support sustainable growth for region City of Charlotte Rapid Population Growth In 1998 the Charlotte Mecklenburg population was projected to grow by about 385,000 people over the next 30 years a 66% increase. 1995 2025 Mecklenburg County projected population 580,000 965,000 growth in 1998 In 2014 the US Census Bureau estimated Mecklenburg County’s population is already over a million people at 1,012,539. That is a 75% increase from 1995. We have reached our projections a full 10 years early. City of Charlotte Rapid Population Growth Population Percent Change 2000-2014 Charlotte 50% Towns within Mecklenburg and the surrounding Davidson 68% counties have also experienced rapid growth Cornelius 130% since the adoption of the 2025 system plan. Huntersville 107% Matthews 35% With so many new residents there is the Mint Hill 67% opportunity to engage a much larger population. -

Page 1 MEET CHARLOTTE MEET CHARLOTTE

EXPERIENCEMEET THE MOMENTUM MEET CHARLOTTE CHARLOTTE SEE WHY MAJOR COMPANIES TAP INTO CHARLOTTE’S ENERGY TO ESTABLISH NEW HQS. MOMENTUM. Charlotte teems with activity. This is a city that is luring new residents by the day and major new corporate headquarters practically by the month. Why is Charlotte such a kinetic environment? The pillars of talent to propel healthy businesses, low cost of living to attract young workers, ENERGY. proactive city government to encourage innovative companies, and an environment that appeals to weekend adventurers and new families alike. CHARLOTTEIt’s a city that works hard and plays well, with a booming corporate IS landscape that welcomes newcomers and makes them feel as if they’re DYNAMICPOSITIVITY. being ushered into an inclusive and highly desirable community. 02 06 INDUSTRIES 05 HEADQUARTERS & HISTORY 07 COMMERCE IN CHARLOTTE 09 TALENT & AFFORDABILITY 10 INNOVATION 11 EDUCATION & JOBS 12 UNIVERSITIES 14 CHARLOTTE LIVING 13 CHARLOTTECOMMUNITY-DRIVEN & WORLDIS CLASS 16 CHARLOTTE CULTURE 19 PUTTING CHARLOTTE 17 TRANSPORTATION & INFRASTRUCTURE BUSINESSES ON THE MAP TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 21 RESILIENCE & RESOLVE 22 COMMUNITY RESPONSE DYNAMIC23 MOMENTUM & VISION 25 CONTACT US 04 CHARLOTTE’S HERITAGE TARGET INDUSTRIES TARGET OPERATIONS FUELS ITS MOMENTUM A CITY OF INDUSTRY The office buildings and warehouses of Charlotte bustle Charlotte is a city built on commerce. Growing healthy, groundbreaking businesses FINANCE HEADQUARTERS with activity. Buttoned-down bankers collaborate with is at the core of Charlotte’s DNA. The energy that flows through Charlotte’s business freewheeling fintech experts changing the future of community starts with its students and young workforce and continues up to C-Suites. -

You Can Get There from Here Get There

YOU CAN GET THERE FROM HERE FACILITIES MASTER PLAN 2010 - 2020 Acknowledgements Howard Community College embarked on an exciting year-long campus master planning process to establish a framework for the orderly development of all capital improvements that support the mission, vision, values, and strategic initiatives of the College. The successful master planning process included a comprehensive look at the physical environment of the campus and how that environment helps the College succeed in its educational mission. The campus master planning initiative provided an exciting opportunity for the entire community to participate in shaping a critical aspect of the College's future. The Facilities Master Plan was prepared with support and input from the College, including the Board of Trustees, the College’s faculty, staff and students, and a Steering Committee. The consultant team acknowledges this important input, with many thanks to the following: Board of Trustees T. James Truby, Chair Katherine K. Rensin, Vice Chair Roberta E. Dillow Kevin J. Doyle Mary S. Esmond Patrick L. Huddie, Ph.D. Mr. Louis G. Hutt, Jr., Esq., C.P.A. Kathleen B. Hetherington, Ed.D., Secretary-Treasurer Steering Committee Roberta E. Dillow, Board of Trustees Kathleen B. Hetherington, Ed.D., President Lynn Coleman, Vice President of Administration and Finance Thomas Glaser, Vice President of Information Technology Cindy Peterka, Ph.D., Vice President of Student Services Ronald Roberson, Vice President of Academic Affairs Shelly Bilello, Capital Programs Administrator -

Directory of County Officials 2019-2020 WE’VE GOT GREAT ENERGY

Maryland Association of Counties Maryland Association of Counties Directory of County Officials 2019-2020 WE’VE GOT GREAT ENERGY. For over 20 years, we’ve been providing competitive electricity and natural gas supply, renewable energy and carbon offsets to state and local governments across the Mid-Atlantic. ENERGY FOR YOUR HOME OR BUSINESS WGLEnergy.com COLLEGECOLLEGECOLLEGECOLLEGECOLLEGECOLLEGECOLLEGECOLLEGECOLLEGE OF OF OF OF OFOF PUBLICOF OFPUBLICPUBLIC PUBLICPUBLIC PUBLIC PUBLIC PUBLIC AFFAIRS AFFAIRS AFFAIRSAFFAIRSAFFAIRS AFFAIRSAFFAIRS AFFAIRSAFFAIRS SCHAEFERSCHAEFERSCHAEFERSCHAEFERSCHAEFERSCHAEFER CENTER CENTER CENTERCENTER CENTERCENTER FOR FOR FORFOR FORPUBLICFOR PUBLIC PUBLICPUBLIC PUBLICPUBLIC POLICY POLICY POLICYPOLICY POLICY POLICY GRADUATE GRADUATEGRADUATEGRADUATEGRADUATE PROGRAMS PROGRAMS PROGRAMS PROGRAMS PROGRAMS SCHAEFERApSCHAEFERApplipeldie dRe Research searchCENTER CENTER & &Consulting Consulting FOR FOR PUBLIC PUBLIC POLICY POLICY GraduateGraduateGRADUATEGRADUATE Programs Programs PROGRAMS thatPROGRAMS that Prepare Prepare SCHAEFERApAppApApplileipepdldil ei ReedRed searchResearchRe searchCENTERsearch && Consulting& Consulting& Consulting Consulting FOR PUBLIC POLICY GraduateGraduateGraduateGRADUATE Programs Programs Programs PROGRAMS that that that Prepare Prepare Prepare ApServicesAppServiceslpielide dRe forRe searchfor searchGovernment Government & &Consulting Consulting StudentsStudentsGraduateGraduate to to Lead LeadPrograms Programs In: In: that that Prepare Prepare ApServicesServicespServiceslServicesied Re forforsearch -

East-West Corridor High Capacity Transit Plan Rapid Transit Evaluation Results

East-West Corridor High Capacity Transit Plan Rapid Transit Evaluation Results About the Corridor The AECOM consultant team conducted a high-level analysis of commuter rail, light rail transit (LRT), streetcar and bus rapid transit (BRT) to determine the most appropriate mode for the East- West Corridor. Based on the corridor fit, ridership capacity, cost per mile to build/operate and available right-of-way, BRT will move forward for more detailed analysis. This fact sheet provides, in more detail, how BRT and LRT compared and why BRT was determined to be the best fit. BRT with LRT Screening Results Below are the similarities and differences between bus rapid transit (BRT) and light rail transit (LRT). Features Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Light Rail Transit (LRT) Service Frequency Frequent service during peak hrs. (5–15 min.) Frequent service during peak hrs. (5–15 min.) Typical Corridor Length 5–25 mi. 10–20 mi. Range of Operating Speed 25–55 MPH 30–55 MPH Right-of-Way Dedicated lanes and/or mixed traffic Dedicated lanes with overhead electrical systems Typical Station Spacing ½ and one mile apart One mile apart, outside of downtowns Level boarding at high-quality stations Level boarding at high-quality stations Vehicle Types 40- or 60-ft. buses that have multiple doors 1–3 car trains; low floor vehicles Technology Traffic signal priority Traffic signal priority Real-time passenger info Real-time passenger info Off-board fare payment Off-board fare payment Typical Operating Cost per Hr. $100–$200 $200–$400 Typical Capital Cost per Mi. $2.5 million–$20 million $140 million+ Ridership Capacity by Mode Best Poor Current East-West Corridor Ridership (6.9k–8.7k riders) Modern Streetcar Light Rail Transit (1.5k–6k riders) (20k–90k riders) Bus Rapid Transit (4k–15k riders) Commuter Rail (3k–20k riders) Ridership Mode Capacity by 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 25,000 30,000 35,000 40,000 45,000 50,000 The chart above demonstrates that BRT and commuter rail both have the needed capacity to meet ridership needs.