Download Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Angel Locsin Prays for Her Basher You Can Look but Not Touch How

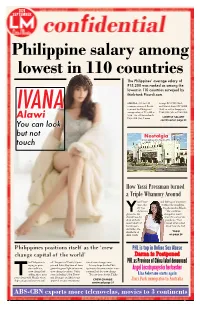

2020 SEPTEMBER Philippine salary among lowest in 110 countries The Philippines’ average salary of P15,200 was ranked as among the Do every act of your life as if it were your last. lowest in 110 countries surveyed by Marcus Aurelius think-tank Picordi.com. MANILA - Of the 110 bourg’s P198,500 (2nd), countries reviewed, Picodi. and United States’ P174,000 com said the Philippines’ (3rd), as well as Singapore’s IVANA average salary of P15,200 is P168,900 (5th) at P168,900, 95th – far-off Switzerland’s Alawi P296,200 (1st), Luxem- LOWEST SALARY continued on page 24 You can look but not Nostalgia Manila Metropolitan Theatre 1931 touch How Yassi Pressman turned a Triple Whammy Around assi Press- and feelings of uncertain- man , the ty when the lockdown 25-year- was declared in March. Yold actress “The world has glowed as she changed so much shared how she since the start of the dealt with the pandemic,” Yassi recent death of mused when asked her 90-year- about how she had old father, the YASSI shutdown of on page 26 ABS-CBN Philippines positions itself as the ‘crew PHL is top in Online Sex Abuse change capital of the world’ Darna is Postponed he Philippines is off. The ports of Panila, Capin- tional crew changes soon. PHL as Province of China label denounced trying to posi- pin and Subic Bay have all been It is my hope for the Phil- tion itself as a given the green light to become ippines to become a major inter- Angel Locsin prays for her basher crew change hub, crew change locations. -

Fairytales Often Start with Once Upon a Time, in a Beautiful Kingdom... but What About If It Starts with Once Upon a Time, in A

fairytales often start with once upon a time, in a beautiful kingdom... but what about if it starts with once upon a time, in a coffee shop, can't it be called a fairytale? it's weird, though. Starting a fairytale in a coffe shop?! But the question make s perfect sense to me.. --Denise The "far far away kingdom" can be very perfect. You can imagine it with all it's completeness- the love and joy in it. and of course, in fairytales, there are a lways happy endings.-- Gino But then, this perfect place can only be imagined, this place is not for real. S o i choose reality, because in life, there are no perfect places, no perfect peo ple, and.. not all have happy endings. If fairytales give everything to me, and reality gives me the imperfect ones? then i will choose reality. How can i learn if I live in a perfect world? because there is no perfect in life because there is no perfect love If fairytales give me joy, and reality gives me pain? i would choose reality, because love finds its way to hurt people. and there are times that you feel contented because you were able to pass those sorrows. If fairytales give me a perfect kingdom, and reality gives me a coffee shop? then i would choose the coffee shop.. [size=15pt]because this i[/size][/color][size=15pt]s where I met you. :-[ :-[ :-[ :-\ magandang araw! ako si Denise Kaye Lorenzo. nagtapos ako ng business management sa SEIU (St. Elizabeth International University) dyan sa katipunan. -

Gabay Ng Estudyante Sa Pag-Aaral Ng Lumang Tipan

34189_893_co00_cvr.qxd 02-04-2011 12:11 Page 1 LumangLumang TipanTipan Gabay ng Estudyante sa Pag-aaral ng Lumang Tipan Gabay ng Estudyante sa Pag-aaral SEMINARY GABAY NG ESTUDYANTE SA PAG-AARAL Gabay ng Estudyante sa Pag-aaral ng Lumang Tipan Inihanda ng Church Educational System Inilathala ng Ang Simbahan ni Jesucristo ng mga Banal sa mga Huling Araw Salt Lake City, Utah © 2010 ng Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Lahat ng karapatan ay nakalaan Inilimbag sa Estados Unidos ng Amerika Pagsang-ayon sa Ingles: 8/96 Pagsang-ayon sa pagsasalin: 8/96 Pagsasalin ng Old Testament: Student Study Guide Tagalog Mga Nilalaman Ilang Bagay na Dapat Ninyong Malaman Tungkol Genesis 19 Sodoma at Gomorra . 30 sa Lumang Tipan . 1 Genesis 20–21 Isang Pangakong Natupad . 30 Isang Patotoo kay Cristo . 1 Genesis 22 Ang Pag-aalay kay Isaac . 31 Ang Kuwento ng Lumang Tipan . 1 Genesis 23 Namatay si Sara . 32 Paunang Sulyap sa Lumang Tipan—Mga Nilalaman . 1 Genesis 24 Isang Asawa para kay Isaac . 32 Makinabang mula sa Iyong Pag-aaral ng Lumang Tipan . 1 Genesis 25 Ano ang Kahalagahan ng Tipan? . 33 Genesis 26–27 Natanggap ni Jacob ang mga Paano Gamitin ang Manwal na Ito . 2 Pagpapala ng Tipan . 34 Pambungad . 2 Genesis 28 Ang Banal na Karanasan ni Jacob . 34 Pag-unawa sa mga Banal na Kasulatan . 2 Genesis 29 Ang mga Anak ni Jacob, Bahagi 1 . 35 Pag-aaral ng mga Banal na Kasulatan . 2 Genesis 30 Ang mga Anak ni Jacob, Bahagi 2 . 36 Home-Study Seminary Program . 2 Genesis 31 Nilisan ni Jacob ang Padan-aram . -

Silliman Journal a JOURNAL DEVOTED to DISCUSSION and INVESTIGATION in the HUMANITIES and SCIENCES VOLUME 58 NUMBER 1 | JANUARY to JUNE 2017

ARTICLE AUTHOR 1 Silliman Journal A JOURNAL DEVOTED TO DISCUSSION AND INVESTIGATION IN THE HUMANITIES AND SCIENCES VOLUME 58 NUMBER 1 | JANUARY TO JUNE 2017 IN THIS ISSUE Lily Fetalsana-Apura Maria Mercedes Arzadon Rosario Maxino-Baseleres Gina A. Fontejon-Bonior Ian Rosales Casocot Josefina Dizon Benjamina Flor Elenita Garcia Augustus Franco B. Jamias Serlie Jamias Carljoe Javier Zeny Sarabia-Panol Mark Anthony Mujer Quintos Andrea Gomez-Soluta JANUARY TO JUNE 2017 - VOLUME 58 NO. 1 2 ARTICLE TITLE The Silliman Journal is published twice a year under the auspices of Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Philippines. Entered as second class mail matter at Dumaguete City Post Office on 1 September 1954. Copyright © 2017 by the individual authors and Silliman Journal All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors or the publisher. ISSN 0037-5284 Opinions and facts contained in the articles published in this issue of Silliman Journal are the sole responsibility of the individual authors and not of the Editors, the Editorial Board, Silliman Journal, or Silliman University. Annual subscription rates are at PhP600 for local subscribers, and $35 for overseas subscribers. Subscription and orders for current and back issues should be addressed to The Business Manager Silliman Journal Silliman University Main Library 6200 Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental Philippines Issues are also available in microfilm format from University Microfilms International 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor Michigan 48106 USA Other inquiries regarding editorial policies and contributions may be addressed to the Silliman Journal Business Manager or the Editor at the following email address: [email protected]. -

UNEDITED :) Kaya Sorry Sa Mga Typo and Wrong Grammar Chapter 1: the Kiss "I'm So

UNEDITED:)kayasorrysamgatypoandwronggrammar ______________________________________ Chapter1:thekiss "I'msobored" ***sigh*** "LIAN!Parakanamanmatandakungmagbuntonghiningadyan" "sowhat?Angboringkaya!" "tarashopping" "walaakongpera...magboyhauntingnalangtayosamall" "LOKOkatalagaLIAN!!!" "why?Complicatednamanako..." "status....complicated..yeahright...somanlalalakika?" "why?Ididn'tsaidthat...andbesideshe'scheatingonme...sowhycooloff? Dinalangbreaknakakabwiset" "ehbakitkakasipumayagnamagcooloffkayo?" "sinabikosakanyabreak..sabiniyacooloff...nagngongolektangbabaeeh...bus et!" Anywaykaninapakaminaguusapditodiniyopakilalakausapko...simarieyan bestfriendforeverko!Haha.... "lokaretka!Buraot!Halikananga!Malltayo...magcheatkanadin!Tatkeyan"w hatatermburaothaha... Lokodintoeh...kalamomabaitmayamayadamingsalitangsinasabinadimonan amamalayanXD "wagtayobumiliah...walaakongperaeh...kainlang" "aykayakatumatabaeh" "wagkanaepal...kelangankongtabamuahahaha" "adikkatalagaLian...pasalamatkagwapongtitomoatnungasawaniya" "huh?Anungconnect???Tandanamgayun...trentana" "dikayahalata...gandangasawaniyasi...." "siateAllyna..." "ooyunnga!...nagtatakalangako..bakitsakanyaatetawagmo?Bakitditita?" "ehtripkolang..mulanungbataakoatenatawagkosakanyaeh" "taranangabansot!...magboyhauntingpatayodiba?"Marie "tarana!...kotsemo?" "oonasigena!..." Yes!!!Dimababawasangasulinakohehe..... AkongapalasiLian...18naako...weh?Tandanaba?Dipanamaneh....nagaral akosatexasngilangtaon..tasnunglumipatakoditopinas..eto...4thyrhigh schoolpalangako...patinamansiMarieeh.Sabaykasikaminitolumipat...actu -

Sarah Balabagan, from Muslim to Christian by Rodel Rodis Ref.: INQUIRER.Net First Posted 11:49:00 04/08/2009

Sarah Balabagan, from Muslim to Christian By Rodel Rodis ref.: INQUIRER.net First Posted 11:49:00 04/08/2009 Filed Under: Crime and Law and Justice, Crime, Overseas Employment CALIFORNIA, United States?A week before Good Friday, I visited the Jesus is Lord church in Daly City to hear Sarah Balabagan, a Muslim turned Christian, describe her ordeal in the Middle East, a story that was so compelling it was made into an award-winning film in 1997. After an introduction from Pastor Bobby Singh, Sarah ascended the church pulpit and placed her notes on the podium, humbly apologizing to the congregation that she had to write down her speech as she did not want to be at a loss for words in English. But Sarah need not have worried as she expressed herself exceptionally well. Sarah grew up in a poor Muslim family in the town of Sultan Kudarat in Maguindanao province. How poor? She had 13 brothers and sisters but when one of them got really sick, they would just watch helplessly by as the medical condition of the brother or sister deteriorated until he/she eventually died. Her parents had no money at all for medical care so only six of her siblings survived early childhood diseases. Sarah realized early on that education was her ticket out of the incredible poverty she was born into, so she worked as a maid for relatives just to be able to go to school in return for a wage. But that only got her through fifth grade. At the age of 14, she decided to seek employment abroad. -

Overcoming Filipino Worries

The Life-Changing Magazine No. 337 Vol. 31 APRIL 2018 Love Is Service Fight the Relationship Drift How to Help OFWs in Their Finances OFW: OVERCOMING FILIPINO KERYGMA BARCODE.pdf 11/16/06W O5:43:58RRIES PM Philippines P100 US $8.14 AUS $8.14 AMB. GRACE RELUCIO-PRINCESA Euro 5.07 UK 4.49 The newly-confirmed Philippine ambassador to the Vatican CDN $7.95 SING $9.42 HK $51.83 opens up about her love for God, our country, RUPIAH 103,000 and the Filipinos abroad God Wants to Be in Your Every Season The rituals and traditions that complement our faith can be overwhelming. Or they may seem archaic to others that their response is to become indifferent to these practices and celebrations. That’s why this book is a breath of fresh air to those who want to enliven their faith. Through this soul-kindling collection of homilies, Fr. Bob McConaghy invites us to take God’s hand and experience His love and presence in every season of the liturgical year. Father Bob gives light to theological truths by presenting them in easy- to-digest stories and insights. He gives practical ways to live out your faith during Lent, Easter, Advent, Christmas, and the Ordinary Time. Let your spirit soak in love and grace at every season of the year as you deepen your relationship with the Lord. “Father Bob has a gift of delivering the truth from a fresh, different perspective. This book will help you embrace the teachings and traditions of our Catholic Church more. -

Migrant Labor & the Moral Imperative: Filipino Workers

MIGRANT LABOR & THE MORAL IMPERATIVE: FILIPINO WORKERS IN QATAR AND THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES IN THE 21ST CENTURY A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Waverly Dolaman, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. November 27, 2010 Copyright 2010 by Waverly Dolaman All Rights Reserved ii MIGRANT LABOR & THE MORAL IMPERATIVE: FILIPINO WORKERS IN QATAR AND THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES IN THE 21ST CENTURY Waverly Dolaman, B.A. Mentor: Pamela Sodhy, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Migrant work is a critical part of the Philippines’ economy. In 2009, remittances, or money sent back to the Philippines from citizens working abroad, comprised 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). But these earnings often come at a heavy price, as migrant laborers encounter a host of abusive practices at the hands of Filipino recruitment agencies and Middle Eastern employers. The aim of this thesis is threefold. First, it provides information on and exposes this human rights issue, convincing readers of the “moral imperative” to help stop these abuses. Second, it explores the need for migrant workers, and the vulnerability of Filipino workers who do not have adequate work opportunities in the Philippines. Third, it offers solutions to improve working conditions for Filipino workers in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Although the thesis begins with a historical introduction, the scope of the work is the first decade of the twenty-first century, while the countries examined are the Philippines, Qatar and the UAE. -

11 Scales of Sexuality and the Migration of Filipina Overseas

SCALES OF SEXUALITY AND THE MIGRATION OF FILIPINA OVERSEAS CONTRACT WORKERS James A. Tyner INTRODUCTION The magnitude of labor export from the Philippines, both in volume and geographic scope, is without parallel. In 2000 alone, a total of841,628 migrant workers from the Philippines were legally deployed; spatially, they found employment in over 160 countries and territories. Apart from the sheer size ofthe Philippines' overseas employment program, an additional .. noticeable feature is the predominance of female migrants. In 2000, for example, nearly 72 percent of all newly-hired contract 'workers from the Philippines were women. Patterns ofPhilippine overseas employment, thus, are consonant with other identified systemsofinternational migration, namely, the increased "feminization" oftransnational mobility. As one ofthe most striking economic and social phenomena ofrecent times, the feminization ofinternational labor migration raises crucial policy issues and concerns. Lim and Oishi (1996) point out, for instance, that the status of female migrant workers - as women, as migrants/non-nationals, and as workers in gendered segregated labor markets - makes them particularly vulnerable to various forms of discrimination, exploitation, and abuse. Accordingly, scholars ofmigration have acknowledged more so than ever the political ramifications ofthese migration trends. Indeed, Hollifield (2000) • has announced the birth ofa new field ofstudy in the 1980s and 1990s, one he labels the politics ofinternational migration. In particular, Hollifield -

Unveiling HIV Vulnerabilities: Filipino Women Migrant Workers in the Arab States

Unveiling HIV Vulnerabilities: Filipino Women Migrant Workers in the Arab States Action for Health Initiatives (ACHIEVE), Inc. For Ellen, Rina, Sally and Jasmin Thanks for letting us join your journey. Table of Contents Acknowledgements . 5 Foreword . .6 List of Acronyms . .10 Chapter 1: Introduction . .13 Chapter 2: Migration and HIV: Situation and Response. 23 Chapter 3: Review of Related Literature. 35 Chapter 4: Findings. 51 Chapter 5: Discussion and Analysis of Findings. 81 Chapter 6: Conclusions and Recommendations. 95 References. .101 Annexes. 103 Acknowledgements We thank the UNDP – Regional Center Colombo and the UNDP Manila Office for the support they extended in making this research a reality. We wish to convey our deepest gratitude to the Office of the Undersecretary for Migrant Workers Affairs (OUMWA), Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA); the Philippine Embassy in Bahrain, the Philippine Consulate General in Dubai, and the Philippine Overseas Labor Offices in Bahrain and Dubai for facilitating our research in these countries. To the Kanlungan Center Foundation, the Zone One Tondo Organization, the Remedios AIDS Foundation and the Filipino Workers Association in Lebanon for facilitating our interviews with their communities. We also acknowledge the following individuals, who, in their various capacities, helped us through the conduct of this research: Ms. Monica Smith for conducting the data-gathering in Lebanon and for her technical input in this research. Mr. Avelino Munji, Administrative Officer; and, Mr. Arnold Balangit, (Philippine Embassy, Bahrain); Ms. Maribel Marcaida and Mr. Henry Jimenez (Philippine Consulate General, Dubai) for facilitating our visa applications. Hon. Eduardo Pablo Maglaya, Ambassador and Ms. Ella Cecilia Palma (Philippine Embassy, Bahrain) for the warm welcome and assistance. -

Death and the Maid: Work, Violence, and the Filipina in the International Labor Market

(c)1995 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College and the Harvard Women's Law Journal (now The Harvard Women's Law Journal): http://www.law.harvard.edu/students/orgs/jlg/ DEATH AND THE MAID: WORK, VIOLENCE, AND THE FILIPINA IN THE INTERNATIONAL LABOR MARKET DAN GATMAYTAN* If rape is inevitable, relax and enjoy it. —Raul Manglapus, Former Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Republic of the Philippines1 I. GENERAL INTRODUCTION AND ILLUSTRATION A. Introduction The above comment from the former Secretary of Foreign Affairs was made in the course of a Congressional hearing investigating reports that Iraqi soldiers occupying Kuwait were raping Filipina domestic helpers during the Persian Gulf Crisis in 1990. Women's groups attending the hearing called the remark a demonstration of "the low regard of the [Philippine] government for women."2 While improper and offensive, the Secretary's comment captured a common perception that Filipina over- seas domestic helpers are dispensable.3 While the Persian Gulf Crisis focused increased attention on their circumstances, the vulnerability of Filipina overseas contract workers ("OCWs") to violence existed long 230 Harvard Women's Law Journal [Vol. 20 before 1991. Nevertheless, the recent international publicity of violence against OCWs resulted in intense criticism of the Philippine govern- ment's policy of exporting labor. This Article analyzes the Philippine and international legal frame- works for the protection of Filipina overseas domestic helpers4 from violence5 and the effectiveness of these measures. Though the Philippine government's actions do not seem insignificant on paper, violence against these women persists. This Article posits that the Philippine and inter- national legal responses are ineffective. -

Report November 2016

Report November 2016 The Political Economy of the News Media in the Philippines and the Framing of News Stories on the GPH-CNN Peace Process By Crispin C. Maslog Ramon R. Tuazon Revised edition Senior writers Daniel Abunales Jake Soriano Lala Ordenes Researcher writers Asian Institute of Journalism and Communication (AIJC) Ma. Imelda E. Samson November 2016 Project manager Loregene M. Macapugay Administrative officer Contents Executive summary 3 Abbreviations and acronyms 4 I. Introduction and history: the peace process 4 II. Objectives and methodology of the study 5 III. Roles of the news media in conflict reporting 5 IV. Political economy and news coverage 6 1. Reporting on the CNN lacks context 7 V. Current media framing of the peace process 9 VI. Characteristics of media reporting 9 1. Lack of balance in the use of sources 9 2. Reliance on government and military sources 10 3. Peace reporting on Muslim conflict 11 VII. Ownership structure of the Philippine mass media 12 1. Pre-martial law oligarchs 12 2. Martial law oligarchs 12 3. Today’s oligarchs 13 4. Duopoly 14 5. New kid on the block 14 Table 1: Chain of ownership of the Philippine mass media, 2015 15 6. Philippine media’s global reach 18 VIII. The impact of ownership on the peace process 18 IX. The alternative media: going beyond simplistic peace discourse 18 X. Recommendations 21 1. Jumpstart the stalled GPH-CNN peace process 21 2. Stir up public opinion to support the resumption of the peace process 21 3. Upgrade the quantity and quality of peace process coverage 22 4.