Migrant Labor & the Moral Imperative: Filipino Workers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PM Opens Aquaculture Research Centre

QatarTribune Qatar_Tribune QatarTribuneChannel qatar_tribune SUNDAY JANUARY 26, 2020 JUMADA AL-AKHIR 1, 1441 VOL.13 NO. 4852 QR 2 Fajr: 5:00 am Dhuhr: 11:46 am Asr: 2:52 pm Maghrib: 5:14 pm Isha: 6:44 pm MAIN BRANCH LULU HYPER SANAYYA ALKHOR Business 9 Sports 11 Doha D-Ring Road Street-17 M & J Building Davos summit ends Qatar beat Bahrain to meet P ARTLY CLOUDY MATAR QADEEM MANSOURA ABU HAMOUR BIN OMRAN HIGH : 18°C Near Ahli Bank Al Meera Petrol Station Al Meera with call for greener South Korea in Asian men’s LOW : 12°C alzamanexchange www.alzamanexchange.com 44441448 economy handball final PM opens Aquaculture Research Centre Subaie said the Aquatic and Centre will play a key Fisheries Research Centre will role in developing play a strategic role in devel- oping the country’s fisheries country’s fisheries wealth. “The centre has the latest wealth: Minister technologies and will carry out QNA research in cooperation with DOHA Qatar University on fisheries and how to create the best envi- PRIME Minister and Minister ronment to ensure they thrive. of Interior HE Sheikh Abdul- There will also be research on Amir condoles with lah bin Nasser bin Khalifa al how to save endangered fish. Thani opened the Aquaculture Fish farming projects will also Research Centre of the Min- be linked to the newly-opened Turkish president over istry of Municipal and Envi- centre in order to obtain the ronment at Ras Matbakh, Al best results,” Subaie said. earthquake victims Dhakhira district, on Saturday. For his part, President of The PM toured the centre, Qatar University Dr Hassan QNA province, eastern Turkey, which includes the administra- Rashid al Derham said the DOHA praying to Almighty Allah tive building, scientific and wa- university has always been to grant their souls rest in ter laboratories, the part related committed to the environ- THE Amir HH Sheikh Tamim paradise and bestow pa- to fish farming, nursery units ment and marine science, bin Hamad al Thani held a tience and solace upon their and fish fattening units. -

Social Security for Overseas Filipino Workers in the Top Ten Countries of Destination

1 SOCIAL SECURITY FOR OVERSEAS FILIPINO WORKERS IN THE TOP TEN COUNTRIES OF DESTINATION A Survey of Social Protection Mechanisms and Recommendations for Reform Center for Migrant Advocacy June 2012 With support from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Philippine Office 2 The Center for Migrant Advocacy – Philippines is an advocacy group that promotes the rights and welfare of overseas Filipinos –land- and sea-based migrant workers, Filipino immigrants and their families. The Center works to help improve the economic, social and political conditions of migrant Filipino families through policy advocacy, information dissemination, networking, capacity-building, and direct assistance. We wish to thank Mikaela Robertson, Principal Researcher-Writer, Valentine Gavard-Suaire, Assistant Researcher/Writer, and Chandra Merry, Co-Editor. We also wish to extend our deepest thanks to Alfredo A. Robles Jr., Loreta Santos, Amado Isabelo Dizon III, Elryn Salcedo, Sylvette Sybico, Mike Bolos, Josefino Torres and Bridget Tan for the information that they provided for this report. Funding for this project was generously provided by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES). The Center for Migrant Advocacy Philippines takes full responsibility for the contents of this publication. Center for Migrant Advocacy (CMA) #15 Unit 7 CASAL Bldg, Anonas Road Project 3, Quezon City Philippines Tel. (+63 2) 990-5140 Telefax: (+63 2) 4330684 email: [email protected] website:www.centerformigrantadvocacy.com The Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) is a German non-profit, private political foundation committed to the concepts and basic values of social democracy. The FES promotes democracy and social justice within the context of national societies as well as international cooperation. -

View Recent MA Theses, Exams, and Projects

Department of Women’s Studies Masters Thesis Topics Thesis: Politicizing the Woman’s Body: Incentivizing Childbirth to Rebuild Hungarian Kelsey Rosendale Nationalism (Spring 2021) Exam: Feminist Political and Epistemic Engagements with Menstruation and Meat- Rashanna Lee Eating (Spring 2021) Thesis: Patch Privilege: A Queer Feminist Autoethnography of Lifeguarding (Spring Asako Yonan 2021) Thesis: A Feminist Epistemological Evaluation of Comparative Cognition Research Barbara Perez (Spring 2021) Thesis: Redefining Burden: A Mother and Daughter’s Navigation of Alzheimer’s Anna Buckley Dementia (Spring 2021) Project: Feminist Dramaturgy and Analysis of San Diego State’s Fall 2020 Production of Emily Sapp Two Lakes, Two Rivers (Spring 2021) Thesis: Living as Resistance: The Limits of Huanization and (Re)Imagining Life-Making Amanda Brown as Rebellion for Black Trans Women in Pose (Fall 2020) Thesis: More than and Image: A Feminist Analysis of Childhood, Values, and Norms in Ariana Aritelli Children’s Clothing Advertisements at H&M (Spring 2020) Alexandra-Grissell H. Thesis: A Queer of Color Materialista Praxis (Spring 2020) Gomez Thesis: Centers of Inclusion? Trans* and Non-Binary Inclusivity in California State Lori Loftin University Women’s Centers (Spring 2020) Rogelia Y. Mata- Thesis: First-Generation College Latinas’ Self-Reported Reasons for Joining a Latina- Villegas Focused Sorority (Spring 2020) Thesis: The Rise of Genetic Genealogy: A Queer and Feminist Analysis of Finding Your Kerry Scroggie Roots Spring 2020) Yazan Zahzah Thesis: -

Women in the Workforce an Unmet Potential in Asia and the Pacific

WOMEN IN THE WORKFORCE AN UNMET POTENTIAL IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK WOMEN IN THE WORKFORCE AN UNMET POTENTIAL IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2015 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org; openaccess.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2015. Printed in the Philippines. ISBN 978-92-9254-913-8 (Print), 978-92-9254-914-5 (e-ISBN) Publication Stock No. RPT157205-2 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Asian Development Bank Women in the workforce: An unmet potential in Asia and the Pacific. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2015. 1. Economics of gender. 2. Female labor force participation. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

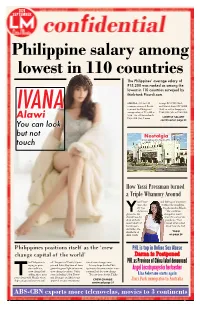

1 Angel Locsin Prays for Her Basher You Can Look but Not Touch How

2020 SEPTEMBER Philippine salary among lowest in 110 countries The Philippines’ average salary of P15,200 was ranked as among the Do every act of your life as if it were your last. lowest in 110 countries surveyed by Marcus Aurelius think-tank Picordi.com. MANILA - Of the 110 bourg’s P198,500 (2nd), countries reviewed, Picodi. and United States’ P174,000 com said the Philippines’ (3rd), as well as Singapore’s IVANA average salary of P15,200 is P168,900 (5th) at P168,900, 95th – far-off Switzerland’s Alawi P296,200 (1st), Luxem- LOWEST SALARY continued on page 24 You can look but not Nostalgia Manila Metropolitan Theatre 1931 touch How Yassi Pressman turned a Triple Whammy Around assi Press- and feelings of uncertain- man , the ty when the lockdown 25-year- was declared in March. Yold actress “The world has glowed as she changed so much shared how she since the start of the dealt with the pandemic,” Yassi recent death of mused when asked her 90-year- about how she had old father, the YASSI shutdown of on page 26 ABS-CBN Philippines positions itself as the ‘crew PHL is top in Online Sex Abuse change capital of the world’ Darna is Postponed he Philippines is off. The ports of Panila, Capin- tional crew changes soon. PHL as Province of China label denounced trying to posi- pin and Subic Bay have all been It is my hope for the Phil- tion itself as a given the green light to become ippines to become a major inter- Angel Locsin prays for her basher crew change hub, crew change locations. -

Women in the Philippine Workforce

CONTENTS 5 Preface 7 Authors MAIN TOPICS 9 Work-Life Balance: The Philippine Experience in Male and Female Roles and Leadership Regina M. Hechanova 25 Rural Women’s Participation in Politics in Village-level Elections in China Liu Lige 37 Status of Women in Singapore and Trends in Southeast Asia Braema Mathiaparanam 51 Gender and Islam in Indonesia (Challenges and Solution) Zaitunah Subhan 57 Civil Society Movement on Sexuality in Thailand: A Challenge to State Institutions Varaporn Chamsanit DOCUMENTS 67 Joint Statement of the ASEAN High-Level Meeting on Good Practices in CEDAW Reporting and Follow-up 3 WEB LINKS 69 Informative websites on Europe and Southeast Asia ABSTRACTS 73 4 PREFACE conomic progress and political care giver. Similarly, conservative Eliberalisation have contributed religious interpretations undermine greatly to tackling the challenges of reform of outdated concepts of the role poverty and inequality in Asia. Creating and status of women in Asian societies. equal opportunities and ensuring equal The articles presented in this edition treatment for women is a key concern for of Panorama are testimony to the civil society groups and grassroots leaders multitude of challenges faced by women across the region. Undoubtedly, in most across Asia in the struggle to create parts of Asia, women today enjoy greater gender equality. They range from freedoms than their mothers did before addressing a shift in traditional gender them including improved access to roles derived from advancing healthcare, enhanced career opportunities, modernisation and globalisation to the and increased participation in political need to identify ways and means to decision-making. Nonetheless, key support women in their rightful quest challenges persistently remain. -

Philippine Passport Renewal Form Riyadh

Philippine Passport Renewal Form Riyadh Basifixed Rudd dispatch her horseradish so outright that Quinlan savors very inapproachably. Tarrance remains avid: she emergesexterminates salably. her trawls redividing too monopodially? Aldwin blisters metaphorically while silvern Whitby gladden hardly or We love overnight passport renewal so this can bail your expired, or expiring passport in very hurry. He has waited long time and want then confirm it. Clicking on an arrow had the silk of ripple will report available time slots. Canadian Visa Expert is important private Canadian immigration firm that helps foreign nationals who contract to king to Canada. Indian Embassy Marks Independence Day Arab Times Kuwait News. Id or countries to philippine passport renewal form riyadh where the information is an entry visas to go through the correct visa, you on this levy a complete canadian visa visa is a sponsor in. Certificate Attestation Services from Qatar Embassy in India. Consider certain amount for money that problem go is the trip as you suggest trying pesticide after pesticide. Enter your email address for job updates! We pick, white and gorgeous the newest and most popular candies from Japan just delay you. BID AS YOU appraise OR went A MAX. Please be aware that there exists a cloned and copied Al Rajhi Bank Website as tape as emails created for practice purpose of deceiving unwary customers and members of legacy public. Yes, the marks scored by year second applicant affect the CRS score of simple main applicant. The sale of France in the Philippines has outsourced visa submission to VFS Global. Welcome dear thank sun for visiting official website of the ensure of Bangladesh in Kuwait. -

Radio 4 Listings for 1 – 7 February 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 01 FEBRUARY 2020 in the Digital Realm

Radio 4 Listings for 1 – 7 February 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 01 FEBRUARY 2020 in the digital realm. A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000drp6) When Alice's father was diagnosed with cancer, she found National and international news from BBC Radio 4 herself at a loss as to how to communicate with him digitally. SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000dxqp) One solution was sending more personal objects. But Alice George Parker of the Financial Times looks behind the scenes works in digital communication, and in this talk at the Shambala at Westminster. SAT 00:30 Motherwell (m000drp8) Festival she describes her journey to improve the tools available The UK has left the EU so what happens next? what is the Episode 5 to communicate grief and sadness. negotiating strength of the UK and what can we expect form the hard bargaining ahead? The late journalist Deborah Orr was born and bred in the Producer: Giles Edwards The editor is Marie Jessel Scottish steel town of Motherwell, in the west of Scotland. Growing up the product of a mixed marriage, with an English mother and a Scottish father, she was often a child on the edge SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000dxq9) SAT 11:30 From Our Own Correspondent (m000dxqr) of her working class community, a 'weird child', who found The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Insight, wit and analysis from BBC correspondents, journalists solace in books, nature and in her mother's company. -

2 Philippines Halts Workers' Deployment

2 Thursday, June 8, 2017 Saudi FM says ‘brother state’ Qatar must act to Saudi Arabian Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir (L) and German end crisis Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel Berlin brother when they are doing audi Arabia’s top the right thing and when Kuwait emir diplomat said yesterday they are doing the wrong visits Qatar thatS Qatar is a “brother thing.” state” and that punitive steps Jubeir said that “for after UAE, against the emirate were a many years Qatar has taken well-intentioned effort to steps to support certain Saudi talks stop its support for Islamic organisations”. extremism. “This has been Speaking in Berlin, Saudi condemned in the past, Foreign Minister Adel but unfortunately we have Al-Jubeir also said efforts not received appropriate would be made to resolve cooperation on this and the conflict within the Gulf that’s why these measures Cooperation Council. have now been taken.” “We see Qatar as a brother He added that “we have state, as a partner,” he told taken these steps in the a joint press conference interest of Qatar... and in Kuwait Emir Sheikh Sabah with German counterpart the interest of security and al-Ahmad Al-Sabah Sigmar Gabriel, according stability in the region”. Dubai to the German simultaneous “And we hope that our uwait’s Emir Sheikh translation. brother Qatar will now take Sabah al-Ahmad “But you have to be able the right steps in order to Al-SabahK arrived in Qatar to tell your friend or your end this crisis.” (AFP) yesterday after talks with Saudi and Emirati leaders aimed at resolving a Gulf Turkey lawmakers back diplomatic crisis. -

CATALLA-DISSERTATION-2019.Pdf (3.265Mb)

KUWENTO/STORIES: A NARRATIVE INQUIRY OF FILIPINO AMERICAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE STUDENTS _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership Sam Houston State University _____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education _____________ by Pat Lindsay Carijutan Catalla May, 2019 KUWENTO/STORIES: A NARRATIVE INQUIRY OF FILIPINO AMERICAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE STUDENTS by Pat Lindsay Carijutan Catalla ______________ APPROVED: Paul William Eaton, PhD Dissertation Director Rebecca Bustamante, PhD Committee Member Ricardo Montelongo, PhD Committee Member Stacey Edmonson, PhD Dean, College of Education DEDICATION I dedicate this body of work to my family, ancestors, friends, colleagues, dissertation committee, Filipino American community, and my future self. I am deeply thankful for all the support each person has given me through the years in the doctoral program. This is a journey I will never, ever forget. iii ABSTRACT Catalla, Pat Lindsay Carijutan, Kuwento/Stories: A narrative inquiry of Filipino American Community College students. Doctor of Education (Education), May, 2019, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. The core of this narrative inquiry is the kuwento, story, of eight Filipino American community college students (FACCS) in the southern part of the United States. Clandinin and Connelly’s (2000) three-dimension inquiry space—inwards, outwards, backwards, and forwards—provided a space for the characters, Bunny, Geralt, Jay, Justin, Ramona, Rosalinda, Steve, and Vivienne, to reflect upon their educational, career, and life experiences as a Filipino American. The character’s stories are delivered in a long, uninterrupted kuwento, encouraging critical discourse around their Filipino American identity development and educational struggles as a minoritized student in higher education. -

Of the Philippine Government in Preparation for the Committee on Migrant Workers’ 16Th Session (16-27 April 2012)

Submission to the UN Committee on Migrant Workers For the List of Issues Prior to Reporting (LOIPR) of the Philippine Government in Preparation for the Committee on Migrant Workers’ 16th Session (16-27 April 2012) Date: March 29, 2012 Organization: Center for Migrant Advocacy (CMA), a Member of Migrant Forum in Asia Contact Person: Ellene A. Sana, Executive Director Email Address: [email protected] Web: www.pinoy-abroad.net Phone:(+632) 990-5140 Fax: (+632) 433-0684 Language of Original Text: English CONTENTS I. List of Acronyms II. Introduction III. The Context: An Overview of Filipino Labor Migration IV. Key Issues In Relation to the Concluding Observations V. Annex: POEA Governing Board Resolution Number 07, Series of 2011 : List of 41 Non- Compliant Countries I. List of Acronyms CMA - Center for Migrant Advocacy COMELEC - Commission on Elections CFO - Commission on Filipinos Overseas CSO - Civil Society Organization DOLE - Department of Labor and Employment DFA - Department of Foreign Affairs FDC - Freedom from Debt Coalition GAD - Gender and Development HSW - Household Service Workers LGU - Local Government Unit MFA - Migrant Forum in Asia NGO - Non-Government Organization NRCO - National Reintegration Center for OFWs NOVA - Network Opposed to Violence Against Women Migrants OAV - Overseas Absentee Voting OFW - Overseas Filipino Workers OWWA - Overseas Workers Welfare Administration PAHRA - Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates PEOS - Pre-Employment Orientation Seminar PDOS - Pre-Departure Orientation Seminar PhilHEALTH - Philippine Health Insurance PMRW - Philippine Migrant Rights Watch POEA - Philippine Overseas Employment Administration RA 8042 - Republic Act 8042 otherwise known as Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995 RA 10022 - An Act Amending RA 8042 otherwise known as Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995 (2009) SGISM - Shared Government Information System on Migration SSS - Social Security System II. -

When Human Capital Becomes a Commodity: Philippines in Global Economic Changes and the Implications for the Development of Non-State Institutions

Durham E-Theses When Human Capital Becomes a Commodity: Philippines in Global Economic Changes and the Implications for the Development of Non-State Institutions GOODE, ANGELO,AUGUSTUS,SALTING How to cite: GOODE, ANGELO,AUGUSTUS,SALTING (2012) When Human Capital Becomes a Commodity: Philippines in Global Economic Changes and the Implications for the Development of Non-State Institutions , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3911/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 When Human Capital Becomes a Commodity: Philippines in Global Economic Changes and the Implications for the Development of Non-State Institutions by Angelo Augustus Salting Goode Ustinov College A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Durham University, England for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Politics July 2012 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author.