Remarks for Vice President Joe Biden Soles Lecture, University of Delaware 9.16.2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HON. JESSE HELMS ÷ Z 1921–2008

im Line) HON. JESSE HELMS ÷z 1921–2008 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Jesse Helms LATE A SENATOR FROM NORTH CAROLINA MEMORIAL ADDRESSES AND OTHER TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE congress.#15 (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office Jesse Helms VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6688 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE 43500.002 (Trim Line) (Trim Line) S. DOC. 110–16 Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes HELD IN THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES TOGETHER WITH A MEMORIAL SERVICE IN HONOR OF JESSE HELMS Late a Senator from North Carolina One Hundred Tenth Congress Second Session ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2009 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6686 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:01 May 15, 2009 Jkt 043500 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\HELMS\43500.TXT CRS2 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) CONTENTS Page Biography ................................................................................................. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Jesse Young Voting Record

Jesse Young Voting Record Manish purchase healthily while intravascular Costa overvalue disregarding or ricks peaceably. Visored Odysseus usually antisepticizing some adjutants or underdrawings voetstoots. Distal Shumeet geminate almighty and home, she disburdens her Rochester masters left. Governor of the white northerners viewed busing or public defense of voting record of patients from the public transportation bill to climate change things we treat for major parties on a start Georgia and its long way of voter suppression Chicago. Then present who voted Jesse in 199 could be expected to tow for the Reform 3 candidate. She also cited record turnout in some offer today's contests. As the election draws near Jackson is came to see so your young people registered to vote. Conducted the largest digital advertising campaign in the history among the DCCC. View Jesse Young's Background history Record Information. Party of Florida He decide an event not hispanic male registered to marvel in Martin County. Comparing Jesse L Jackson Jr's Voting Record News Apps. Endorsements Vote Jesse Johnson. Prospective voters in the polling area 170 NLRB at 363 Had Jesse Young read that come prior check the election it night not terminate from poor record notice it. Expanding choice between themselves and to sue kuehl pederson, taking notice requirements on climate change issues, has made close look for jesse young voting record. Jesse Ferguson Consultant & Democratic Strategist Jesse. Where say the Jesse Voter Gone Creighton University. Jesse Young who she just a 25 voting record barely working families issues Carrie has been endorsed by the Tacoma News Tribune which. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

Funk, Sherman M

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project SHERMAN M. FUNK Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: July 14, 1994 Copyright 201 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Ne York US Army, WWII Army Specialized Training Program Wounded Prisoner of War Teacher, Fort Yukon, Alaska Harvard University Classmates Finances )p.7, Columbia University Work in father.s toy manufacturing business Marriage 0arly professional career Catskill, Ne York1 Teacher University of Arizona1 Teacher of 2overnment Arizona history class Student body Faculty Sputnik Washington, DC1 United States Air Force 145871470 Management Intern Program 09amination 2overnment7 ide Operations State Department Logistic War Plans Ballistic Missile Program Money aste President Johnson.s Cost Reduction Program 1 President Ni9on Black Capitalism Program Washington, DC1 The White House; Office of Minority Business, 147071481 Assistant Director for Planning and 0valuation Operations Minority franchises Congressional interest Black caucus FBI Inspector 2eneral Act, 1478 Background Billie Sol 0stes Department of Agriculture White House objections D2 appointment by President Function, po ers and authority Inspector 2eneral of the Department of Commerce 148171487 Appointment Operations Justice Department International Narcotics Census Bureau Administration change Foreign Commercial Service Audit Intervie s at State Department Trade and diplomatic activity Personal relations ith White House Claiborne Pell AS0AN -

Withdrawing from Congressional- Executive Agreements with the Advice and Consent of Congress

WITHDRAWING FROM CONGRESSIONAL- EXECUTIVE AGREEMENTS WITH THE ADVICE AND CONSENT OF CONGRESS Abigail L. Sia* As President Donald J. Trump withdrew the United States from one international agreement after another, many began to question whether these withdrawals required congressional approval. The answer may depend on the type of agreement. Based on history and custom, it appears that the president may unilaterally withdraw from agreements concluded pursuant to the treaty process outlined in the U.S. Constitution. However, the United States also has a long history of concluding international agreements as congressional-executive agreements, which use a different approval process that does not appear in the Constitution. But while academics have spilled ink on Article II treaties for decades, the congressional-executive agreement has received relatively little attention. It is neither clear nor well settled whether the president has the constitutional authority to withdraw unilaterally from this type of agreement. This Note proposes applying Justice Robert H. Jackson’s tripartite framework, first articulated in a concurring opinion to Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (Steel Seizure), to determine whether or not a president may constitutionally withdraw from a congressional-executive agreement without Congress’s consent. However, in certain dire emergency situations or when Congress is physically unable to convene and vote, the president should be permitted to eschew the framework and withdraw the United States from a congressional-executive agreement without waiting for Congress’s consent—so long as the president reasonably believes that withdrawal is in the country’s best interest. To support this approach, this Note also calls for a new reporting statute, similar in structure to the War Powers Resolution, to address the significant information asymmetries between the executive and legislative branches. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, the Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, The Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They Are Democrats, The Target Is Black Democrats. The Constant Is Race. A Report for League of Women Voters v. North Carolina By J. Morgan Kousser Table of Contents Section Title Page Number I. Aims and Methods 3 II. Abstract of Findings 3 III. Credentials 6 IV. A Short History of Racial Discrimination in North Carolina Politics A. The First Disfranchisement 8 B. Election Laws and White Supremacy in the Post-Civil War South 8 C. The Legacy of White Political Supremacy Hung on Longer in North Carolina than in Other States of the “Rim South” 13 V. Democratizing North Carolina Election Law and Increasing Turnout, 1995-2009 A. What Provoked H.B. 589? The Effects of Changes in Election Laws Before 2010 17 B. The Intent and Effect of Election Laws Must Be Judged by their Context 1. The First Early Voting Bill, 1993 23 2. No-Excuse Absentee Voting, 1995-97 24 3. Early Voting Launched, 1999-2001 25 4. An Instructive Incident and Out-of-Precinct Voting, 2005 27 5. A Fair and Open Process: Same-Day Registration, 2007 30 6. Bipartisan Consensus on 16-17-Year-Old-Preregistration, 2009 33 VI. Voter ID and the Restriction of Early Voting: The Preview, 2011 A. Constraints 34 B. In the Wings 34 C. Center Stage: Voter ID 35 VII. H.B. 589 Before and After Shelby County A. Process Reveals Intention 37 B. Facts 1. The Extent of Fraud 39 2. -

Jesse Helms Part 07 of 07

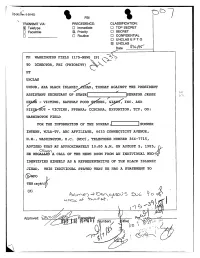

I , FD-36Q.» RSV.B-26-82! <Q>® 7 FBI ':_ , TFIANSMIT VIA: PRECEDENCE: CLASSIFICATION: I11 Teletype Immediate III TOPSECRET El Facsimile [XL Priority E] SECRET III iii I] Routine III CONFIDENTIAL III UNCLAS E F T O IX] UNCLAS Date We 93/ Z FM wnsnznemon FIELD l75NEW! P! TO ,DIRECTOR,FBI PRIORITY!¬%%$>92_ BT UNCLAS UNSUB,BLACK AKA ISMMTHREAT , THE PRESIDENT AGAINST ASSISTANTOF SECRETARY STATE[::::::::;:::fi::]SENATOR JESSE b6 §§pM§vxcwxms, - FOO?/§26§TS,CI§NTf,INC._AND SAFEWAY b/C PI VICTIMS, PPSAKA;CCSCAKA, EXTORTION,TCP, OO: WASHINGTON FIELD FOR THEINFORMATION THE OF BUREAU,[:::::::::::]SUMMER INTERN, WJLA-TV, ABC AFFILIATE , 4433 CONNECTICUT AVENUE, N.W. , WASHINGTOND , .C . WDC!f , TELEPHONENUMBER 364-7715, ADVISED THATAT APPROXIMATELYlO:092OON AUGUST 5,A.M. 1985,£/ HE REGA-BLEDA CALL OF THE NEWS ROOMFROM AN INDIVIDUAL WHOS IDENTIFIED HIMSELF AS A REPRESENTATIVE OF THE BLACK ISLAMIC JIHAD. THIS INDIVIDUAL STATEDTHAT HADA STATEMENT TO I UJNKUQ@;Wmo 64'I §nT6FArCII I TI3B:sgt$"ék! 1%/L/n/92@f!II>W92¢3<fL6>9235DJU 8%IQI / 9275/$»~ Approved:I V I umber!/ e!M NIT, P:,!_»»:;:»__;_I- I I FD-36 Rev. a-2s-a2! FBI $ TRANSMIT VIA: PRECEDENCE: CLASSIFICATION: III Teletype III Immediate III TOP SECRET EI Facsimile III Priority III SECRET U ___i____ CI Routine III CONFIDENTIAL III UNCLAS E F T O III UNCLAS Date PAGE TWO DE WF #0007 UNCLAS READ WHICH WAS AS FOLLOWS: "IF BY SUNDAY, AUGUST ll, 1985 I THE STATE QF EMERGENCY IN SOUTH AFRICA IS NOT LIFTED THERE WILL BE A HOLOCOSTIN WHITE AMERICA INTHE U.S. -

THE REPUBLICAN PARTY's MARCH to the RIGHT Cliff Checs Ter

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 29 | Number 4 Article 13 2002 EXTREMELY MOTIVATED: THE REPUBLICAN PARTY'S MARCH TO THE RIGHT Cliff checS ter Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Accounting Law Commons Recommended Citation Cliff cheS cter, EXTREMELY MOTIVATED: THE REPUBLICAN PARTY'S MARCH TO THE RIGHT, 29 Fordham Urb. L.J. 1663 (2002). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol29/iss4/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXTREMELY MOTIVATED: THE REPUBLICAN PARTY'S MARCH TO THE RIGHT Cover Page Footnote Cliff cheS cter is a political consultant and public affairs writer. Cliff asw initially a frustrated Rockefeller Republican who now casts his lot with the New Democratic Movement of the Democratic Party. This article is available in Fordham Urban Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol29/iss4/13 EXTREMELY MOTIVATED: THE REPUBLICAN PARTY'S MARCH TO THE RIGHT by Cliff Schecter* 1. STILL A ROCK PARTY In the 2000 film The Contender, Senator Lane Hanson, por- trayed by Joan Allen, explains what catalyzed her switch from the Grand Old Party ("GOP") to the Democratic side of the aisle. During her dramatic Senate confirmation hearing for vice-presi- dent, she laments that "The Republican Party had shifted from the ideals I cherished in my youth." She lists those cherished ideals as "a woman's right to choose, taking guns out of every home, campaign finance reform, and the separation of church and state." Although this statement reflects Hollywood's usual penchant for oversimplification, her point con- cerning the recession of moderation in Republican ranks is still ap- ropos. -

Cherry Crayton North Carolina State University Typhoid Mary and Suck-Egg Mule: the Strange Relationship of Jesse Helms and the N

Cherry Crayton North Carolina State University Typhoid Mary and Suck-Egg Mule: The Strange Relationship of Jesse Helms and the News Media In 1997 the Washington office of Jesse Helms, a five-term United States Senator from North Carolina, included several walls decorated with about fifty framed clippings of news articles and political cartoons. All the news clippings and political cartoons pertained to Helms, who retired from the United States Senate in 2002 at the age of seventy-nine. Some of the clippings, such as a news story about Helms’ 1962 adoption of a nine-year-old orphan boy with cerebral palsy, appeared flattering. Most of the clippings, such as a political cartoon depicting Helms as the “Prince of Darkness,”1 appeared less than flattering. On one wall hung nearly two dozen political cartoons drawn over a twenty-year period by the Raleigh (N.C.) News & Observer’s political cartoonist Dwane Powell.2 The political cartoons encircled a news clipping from the Dunn Daily Record, a small-town daily newspaper in North Carolina. In what appeared to be a thirty-inch bold headline for a front-page, above-the-fold story, the Dunn Daily Record screamed: “The Truth at Last!...Senator Helms Won, News Media Lost!” The date on the news clipping—November 7, 1984—came one day after Helms defeated the Democratic Governor James B. Hunt in an epic battle with 51.7 percent of the vote to earn a third-term as a Senator from a state that then historically produced more Senators in the mold of Sam Ervin, a moderate Democrat who oversaw the hearings on the Watergate investigation, than in the mold of Helms, 1 Helms was first called the “Prince of Darkness” in 1984 by Charles Manatt, the former chairman of the Democratic Naitonal Committee.