Valley Segments, Stream Reaches, and Channel Units

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geomorphic Classification of Rivers

9.36 Geomorphic Classification of Rivers JM Buffington, U.S. Forest Service, Boise, ID, USA DR Montgomery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Published by Elsevier Inc. 9.36.1 Introduction 730 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification 730 9.36.3 Types of Channel Classification 731 9.36.3.1 Stream Order 731 9.36.3.2 Process Domains 732 9.36.3.3 Channel Pattern 732 9.36.3.4 Channel–Floodplain Interactions 735 9.36.3.5 Bed Material and Mobility 737 9.36.3.6 Channel Units 739 9.36.3.7 Hierarchical Classifications 739 9.36.3.8 Statistical Classifications 745 9.36.4 Use and Compatibility of Channel Classifications 745 9.36.5 The Rise and Fall of Classifications: Why Are Some Channel Classifications More Used Than Others? 747 9.36.6 Future Needs and Directions 753 9.36.6.1 Standardization and Sample Size 753 9.36.6.2 Remote Sensing 754 9.36.7 Conclusion 755 Acknowledgements 756 References 756 Appendix 762 9.36.1 Introduction 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification Over the last several decades, environmental legislation and a A basic tenet in geomorphology is that ‘form implies process.’As growing awareness of historical human disturbance to rivers such, numerous geomorphic classifications have been de- worldwide (Schumm, 1977; Collins et al., 2003; Surian and veloped for landscapes (Davis, 1899), hillslopes (Varnes, 1958), Rinaldi, 2003; Nilsson et al., 2005; Chin, 2006; Walter and and rivers (Section 9.36.3). The form–process paradigm is a Merritts, 2008) have fostered unprecedented collaboration potentially powerful tool for conducting quantitative geo- among scientists, land managers, and stakeholders to better morphic investigations. -

Seasonal Flooding Affects Habitat and Landscape Dynamics of a Gravel

Seasonal flooding affects habitat and landscape dynamics of a gravel-bed river floodplain Katelyn P. Driscoll1,2,5 and F. Richard Hauer1,3,4,6 1Systems Ecology Graduate Program, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana 59812 USA 2Rocky Mountain Research Station, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87102 USA 3Flathead Lake Biological Station, University of Montana, Polson, Montana 59806 USA 4Montana Institute on Ecosystems, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana 59812 USA Abstract: Floodplains are comprised of aquatic and terrestrial habitats that are reshaped frequently by hydrologic processes that operate at multiple spatial and temporal scales. It is well established that hydrologic and geomorphic dynamics are the primary drivers of habitat change in river floodplains over extended time periods. However, the effect of fluctuating discharge on floodplain habitat structure during seasonal flooding is less well understood. We collected ultra-high resolution digital multispectral imagery of a gravel-bed river floodplain in western Montana on 6 dates during a typical seasonal flood pulse and used it to quantify changes in habitat abundance and diversity as- sociated with annual flooding. We observed significant changes in areal abundance of many habitat types, such as riffles, runs, shallow shorelines, and overbank flow. However, the relative abundance of some habitats, such as back- waters, springbrooks, pools, and ponds, changed very little. We also examined habitat transition patterns through- out the flood pulse. Few habitat transitions occurred in the main channel, which was dominated by riffle and run habitat. In contrast, in the near-channel, scoured habitats of the floodplain were dominated by cobble bars at low flows but transitioned to isolated flood channels at moderate discharge. -

Culvert Design Transportation & the Environment Conference December 3, 2014 Chris Freiburger – Fisheries Division - DNR Perched Piping

Culvert Design Transportation & the Environment Conference December 3, 2014 Chris Freiburger – Fisheries Division - DNR Perched Piping Blockage Sediment What are we after? •Natural and dynamic stream channel •Passage of all aquatic organisms •Low maintenance, flood-resilient road Sizing & Placement of Stream Culverts The Stream Will Tell You! •Match Culvert Width to Bankfull Stream Width •Extend Culvert Length through side slope toe •Set Culvert Slope same as Stream Slope •Bury Culvert 1/6th Bankfull Stream Width •Offset Multiple Culverts (floodplain ~ splits lower buried one) (higher one ~ 1 ft. higher) •Align Culvert with Stream (or dig with stream sinuosity) •Consider Headcuts and Cut-Offs Dr. Sandy Verry Chief Research Hydrologist Forest Service Mesboac Culvert Design – 0’ • Match 3’ Bankfull width 6’ • Extend Culvert to side slope toe • Set on Channel Slope Set Slope Failure to set culverts on the same slope th as the stream (and bury them 1/6 widthBKF) is the single reason that many culverts do not allow for fish passage! Slope can be measured as: Slope along the bank (wider variation, than thalweg) Slope of the water surface (big errors at low flow or in flooded channels, good at moderate to bankfull flows) Slope of the thalweg (this, by far, is the best one) Measure a longitudinal profile to allow the precise placement of culverts. Precision Setting is the key to a fully functional riffle culvert installation At each point riffle 1. Bankfull riffle 2. Water surface Setting the elevation 3. Thalweg of the culvert invert True North Backsight upstream & riffle Benchmark downstream assures success! riffle riffle Measure Bankfull elevation, water surface elevation, and major thalweg topographic breaks (riffle top, riffle bottom, pool bottom), at each station, on the longitudinal profile 1997 LITTLE POKEGAMA CREEK PLOT 7 LONGITUDINAL 1003 1002 1001 1000 FT - 999 998 Bankfull elevation 997 ELEVATION 996 Slope = 0.0191 Water Surface elevation 995 Thalweg elevation 994 993 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 THALWEG DISTANCE-FT 1. -

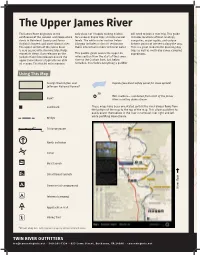

The Upper James River

Waterproof The Upper James River The James River originates at the only class I or II rapids making it ideal will need to plan a river trip. This guide A Paddle Guide to the Upper confluence of the Jackson and Cowpasture for canoe or kayak trips at normal water includes locations of boat landings, rivers in Botetourt County and forms levels. The white water section below campsites, major rapids, and unique Virginia’s longest and most famous river. Glasgow includes a class III section for historic points of interests along the way. The upper section of the James River those interested in more technical water. This is a great resource for planning day is very scenic with stunning Blue Ridge trips as well as multi-day canoe camping mountain views. Dam releases on the This paddle guide covers the upper 64 expeditions. Jackson River flow releases ensure the miles section from the start of the James upper James River is typically run able river to the Cushaw Dam, just below all season. The first 60 miles contain Snowden. It includes everything a paddler Using This Map George Washington and Rapids (See River Safety panel for class system) Jefferson National Forrest* 30 Mile markers— numbered from start of the James Park* River counting down stream Landmark These maps have been orientated so that the river always flows from the bottom of the map to the top of the map. This allows paddlers to easily orient themselves in the river in terms of river right and left while paddling downstream. Bridge 1km Distance gauge 0 1mi North indicator Canal Boat launch Small boat launch Commercial campground River flow River Informal camping Appalachian Trail Hiking Trail *All land along river bank is private property unless noted otherwise. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia Creating an Annotated Sketch Map of Southeast Asia By Michelle Crane Teacher Consultant for the Texas Alliance for Geographic Education Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 Guiding Question (5 min.) . What processes are responsible for the creation and distribution of the landforms and climates found in Southeast Asia? Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 2 Draw a sketch map (10 min.) . This should be a general sketch . do not try to make your map exactly match the book. Just draw the outline of the region . do not add any features at this time. Use a regular pencil first, so you can erase. Once you are done, trace over it with a black colored pencil. Leave a 1” border around your page. Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 3 Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 4 Looking at your outline map, what two landforms do you see that seem to dominate this region? Predict how these two landforms would affect the people who live in this region? Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 5 Peninsulas & Islands . Mainland SE Asia consists of . Insular SE Asia consists of two large peninsulas thousands of islands . Malay Peninsula . Label these islands in black: . Indochina Peninsula . Sumatra . Label these peninsulas in . Java brown . Sulawesi (Celebes) . Borneo (Kalimantan) . Luzon Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 6 Draw a line on your map to indicate the division between insular and mainland SE Asia. -

Stream Restoration, a Natural Channel Design

Stream Restoration Prep8AICI by the North Carolina Stream Restonltlon Institute and North Carolina Sea Grant INC STATE UNIVERSITY I North Carolina State University and North Carolina A&T State University commit themselves to positive action to secure equal opportunity regardless of race, color, creed, national origin, religion, sex, age or disability. In addition, the two Universities welcome all persons without regard to sexual orientation. Contents Introduction to Fluvial Processes 1 Stream Assessment and Survey Procedures 2 Rosgen Stream-Classification Systems/ Channel Assessment and Validation Procedures 3 Bankfull Verification and Gage Station Analyses 4 Priority Options for Restoring Incised Streams 5 Reference Reach Survey 6 Design Procedures 7 Structures 8 Vegetation Stabilization and Riparian-Buffer Re-establishment 9 Erosion and Sediment-Control Plan 10 Flood Studies 11 Restoration Evaluation and Monitoring 12 References and Resources 13 Appendices Preface Streams and rivers serve many purposes, including water supply, The authors would like to thank the following people for reviewing wildlife habitat, energy generation, transportation and recreation. the document: A stream is a dynamic, complex system that includes not only Micky Clemmons the active channel but also the floodplain and the vegetation Rockie English, Ph.D. along its edges. A natural stream system remains stable while Chris Estes transporting a wide range of flows and sediment produced in its Angela Jessup, P.E. watershed, maintaining a state of "dynamic equilibrium." When Joseph Mickey changes to the channel, floodplain, vegetation, flow or sediment David Penrose supply significantly affect this equilibrium, the stream may Todd St. John become unstable and start adjusting toward a new equilibrium state. -

Build Your Own Plunge Pool

How To Build Your Own DIY Plunge Pool ------------------------------------------------------- Save Up to $10,000 Or More on Your Costs! Includes: Construction Overview, Materials, Cost Breakdowns & More! The “Little” Book that’s worth its Weight in GOLD!!! Copyright © 1999-2016 Revised 9/08/2016 Custom Built Spas The DIY Plunge Pool Build Manual The Fastest Growing “Must Have” for Gen X and Baby Boomers! I don’t think I know anybody who doesn’t enjoy relaxing in a nice clean body of water, warm or cool. And, it’s pretty common knowledge that for most of us, water provides one of the best environments for relaxing and exercise that you can do for yourself. Water exercise is low impact, less strain, good for tired or injured muscles and suitable for just about everyone, regardless of what age they may be or what shape they may be in. A low intensity water type workout is excellent for anyone starting or on their journey of getting back in shape. Maybe you’re just looking for a means to do a low impact cardio type workout. A refreshing water environment is one of the most perfect means to accomplish both a low impact workout and low impact cardio exercises. Best of all you can just stop, float and relax anytime you want. So… just what is a Plunge Pool anyway? Simply put; a plunge pool is much the same as a hot tub, swim spa or exercise pool, but typically without the jets. It can be smaller or sometimes shorter than a typical swim spa. -

Tualatin River Basin Rapid Stream Assessment Technique (RSAT)

Tualatin River Basin Rapid Stream Assessment Technique (RSAT) Watersheds 2000 Field Methods Clean Water Services Watershed Management Division 155 North First Ave Hillsboro, OR 97124 July 2000 Acknowledgements Rapid Stream Assessment Technique Adapted from Rapid Stream Assessment Technique (RSAT) Field Methods 1996 Montgomery County Department of Environmental Protection Division of Water Resources Management Montgomery County, Maryland and Department of Environmental Programs Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments 777 North Capitol St., NE Washington, DC 20002 Rapid Stream Assessment Technique Table of Contents Page I. Introduction.............................................................................. 1 I. Tualatin Basin RSAT Field Protocols..................................... 2 A. Field Survey Preparation, Planning, and Data Organization......................2 A. Stream Flow Characterization Valley Profile, Reach Gradient..................3 Velocity Volume/discharge A. Stream Cross Section Characterization ........................................................4 Bankfull Width Bed Width Wetted Width Average Wetted Depth Maximum Bankfull Depth Over Bank Height Bankfull Height Bank Angle Ratio A. Stream Channel Characterization..................................................................7 Bank Material Bank Stability and Undercut Banks Recent Bed Downcutting Dominant Bed Material Deposition Material Embeddedness A. Water Quality.................................................................................................11 -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion. -

Richard Sullivan, President

Participating Organizations Alliance for a Living Ocean American Littoral Society Arthur Kill Coalition Clean Ocean Action www.CleanOceanAction.org Asbury Park Fishing Club Bayberry Garden Club Bayshore Regional Watershed Council Bayshore Saltwater Flyrodders Belford Seafood Co-op Main Office Institute of Coastal Education Belmar Fishing Club Beneath The Sea 18 Hartshorne Drive 3419 Pacific Avenue Bergen Save the Watershed Action Network P.O. Box 505, Sandy Hook P.O. Box 1098 Berkeley Shores Homeowners Civic Association Wildwood, NJ 08260-7098 Cape May Environmental Commission Highlands, NJ 07732-0505 Central Jersey Anglers Voice: 732-872-0111 Voice: 609-729-9262 Citizens Conservation Council of Ocean County Fax: 732-872-8041 Fax: 609-729-1091 Clean Air Campaign, NY Ocean Advocacy [email protected] Coalition Against Toxics [email protected] Coalition for Peace & Justice/Unplug Salem Since 1984 Coast Alliance Coastal Jersey Parrot Head Club Communication Workers of America, Local 1034 Concerned Businesses of COA Concerned Citizens of Bensonhurst Concerned Citizens of COA Concerned Citizens of Montauk Eastern Monmouth Chamber of Commerce Fisher’s Island Conservancy Fisheries Defense Fund May 31, 2006 Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative, Pt. Pleasant Friends of Island Beach State Park Friends of Liberty State Park, NJ Friends of the Boardwalk, NY Garden Club of Englewood Edward Bonner Garden Club of Fair Haven Garden Club of Long Beach Island Garden Club of Middletown US Army Corps of Engineers Garden Club of Morristown -

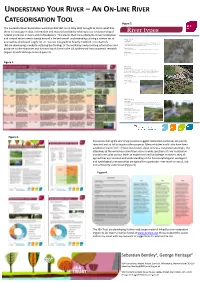

An On-Line River Categorisation Tool

UNDERSTAND YOUR RIVER – AN ON-LINE RIVER ATEGORISATION OOL C T Figure 2. The successful River Restoration workshop that JBA ran in May 2012 brought to sharp relief that there is a vast gap in data, information and material availability relating to our understanding of River types natural processes in rivers and on floodplains. This means that many attempts at river restoration and naturalisation remain based around a limited overall understanding utilising a narrow set of Step-pool Description approaches developed largely for un-reactive low gradient heavily modified river channels. Step-pool river reaches are often composed of large boulder groups, forming steps separated by pools. The pools contain finer sediment. The channel is JBA are developing a website detailing the findings of the workshop and providing information and often stable and the channel gradient is steep. Typical features guidance on the character and functioning of rivers in the UK synthesised from academic research Typical features found in this river system include step-pools and rapids. Flow regime (Figure 1) and field experience (Figure 2). Common flow types include chutes and turbulent flow interspersed with pools. Figure 1. Braided Description Braided river reaches are rare in the UK. They occur in areas of high gradients with high bedload. The channel is characterised by a number of threads, which can be highly dynamic particularly during larger floods. Typical features Typical features found in this river system include rapids, riffles, pools and cut-off channels. Flow regime Common flow types include chutes. Rapid Wandering Description A wandering channel type has the characteristics of a braided and active single-thread system , with a smaller bed material size, a shallower slope and wider valley floor. -

5.1 Coarse Bed Load Sampling

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1997 The initiation of coarse bed load transport in gravel bed streams Andrew C. Whitaker The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Whitaker, Andrew C., "The initiation of coarse bed load transport in gravel bed streams" (1997). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10498. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10498 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.