'Ice-Free Corridor': Some Recent Results from Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Assessment of the Native Fish Stocks of Jasper National Park

A Preliminary Assessment of the Native Fish Stocks of Jasper National Park David W. Mayhood Part 3 of a Fish Management Plan for Jasper National Park Freshwater Research Limited A Preliminary Assessment of the Native Fish Stocks of Jasper National Park David W. Mayhood FWR Freshwater Research Limited Calgary, Alberta Prepared for Canadian Parks Service Jasper National Park Jasper, Alberta Part 3 of a Fish Management Plan for Jasper National Park July 1992 Cover & Title Page. Alexander Bajkov’s drawings of bull trout from Jacques Lake, Jasper National Park (Bajkov 1927:334-335). Top: Bajkov’s Figure 2, captioned “Head of specimen of Salvelinus alpinus malma, [female], 500 mm. in length from Jaques [sic] Lake.” Bottom: Bajkov’s Figure 3, captioned “Head of specimen of Salvelinus alpinus malma, [male], 590 mm. in length, from Jaques [sic] Lake.” Although only sketches, Bajkov’s figures well illustrate the most characteristic features of this most characteristic Jasper native fish. These are: the terminal mouth cleft bisecting the anterior profile at its midpoint, the elongated head with tapered snout, flat skull, long lower jaw, and eyes placed high on the head (Cavender 1980:300-302; compare with Cavender’s Figure 3). The head structure of bull trout is well suited to an ambush-type predatory style, in which the charr rests on the bottom and watches for prey to pass over. ABSTRACT I conducted an extensive survey of published and unpublished documents to identify the native fish stocks of Jasper National Park, describe their original condition, determine if there is anything unusual or especially significant about them, assess their present condition, outline what is known of their biology and life history, and outline what measures should be taken to manage and protect them. -

Bridging the Gap Also Inside

Suburbs Satellites CALGARY & NEIGHBOURING COMMUNITIES& • MAY 2013 Bridging the gap The charm and benefits of small town living near Calgary. Also inside: Spotlight on Southeast Calgary WWW.CALGARYHERALD.COM/SUBS SUBURBSSUBURBS ++ SATELLITESSATELLITES JUNEMAY 20132012 1 everything WE BUILD, WE BUILD around you. Use the power of Baywest’s red pen to make custom changes to your floorplan that suit you. You know there’s a big distinction between “good enough” and “just We build homes from the $400s’ to $1M+ right” and in that gap, exists the opportunity for something better. You wouldn’t think twice about having a suit tailored to fit you, so why compromise on your most important and personal investment? You should expect more. It’s about floorplanning – and inviting you to be a part of that process. Our clients wouldn’t have it any other way. BUILDING IN THESE FINE COMMUNITIES AUBURN BAY SE • RIVERSTONE of CRANSTON SE • MAHOGANY SE • RANCHES OF SILVERADO SW Connect with us: DRESSAGE OF SILVERADO SW • RANCHERS’ RISE in OKOTOKS • NOLAN HILL NW READY-TO-GO | T AILORED | C U S T OM BAYWESTHOMES.COMBAYWESTHOMES.COM 2 SUBURBS + SATELLITES MAY 2013 WWW.CALGARYHERALD.COM/SUBS in this issue Suburbs 2A 21 Airdrie Family moves to Airdrie for house Satellites DIDSBURY CALGARY & NEIGHBOURING COMMUNITIES& • MAY 2013 prices, stays for the schools. 18 Cochrane 582 Historic Bridging the gap The charm and benefits of small downtown CARSTAIRS town living near Calgary. to play a key 4 Chestermere role in the Planners respond to town’s town’s 2 torrid population growth. Also inside: future plans. -

RURAL ECONOMY Ciecnmiiuationofsiishiaig Activity Uthern All

RURAL ECONOMY ciEcnmiIuationofsIishiaig Activity uthern All W Adamowicz, P. BoxaIl, D. Watson and T PLtcrs I I Project Report 92-01 PROJECT REPORT Departmnt of Rural [conom F It R \ ,r u1tur o A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta W. Adamowicz, P. Boxall, D. Watson and T. Peters Project Report 92-01 The authors are Associate Professor, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton; Forest Economist, Forestry Canada, Edmonton; Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton and Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton. A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta Interim Project Report INTROI)UCTION Recreational fishing is one of the most important recreational activities in Alberta. The report on Sports Fishing in Alberta, 1985, states that over 340,000 angling licences were purchased in the province and the total population of anglers exceeded 430,000. Approximately 5.4 million angler days were spent in Alberta and over $130 million was spent on fishing related activities. Clearly, sportsfishing is an important recreational activity and the fishery resource is the source of significant social benefits. A National Angler Survey is conducted every five years. However, the results of this survey are broad and aggregate in nature insofar that they do not address issues about specific sites. It is the purpose of this study to examine in detail the characteristics of anglers, and angling site choices, in the Southern region of Alberta. Fish and Wildlife agencies have collected considerable amounts of bio-physical information on fish habitat, water quality, biology and ecology. -

Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska

Zootaxa 4666 (1): 001–180 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4666.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:BA01E30E-7F64-49AB-910A-7EE6E597A4A4 ZOOTAXA 4666 Checklist of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska VALERIE M. BEHAN-PELLETIER1,3 & ZOË LINDO1 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A0C6, Canada. 2Department of Biology, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by T. Pfingstl: 26 Jul. 2019; published: 6 Sept. 2019 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 VALERIE M. BEHAN-PELLETIER & ZOË LINDO Checklist of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska (Zootaxa 4666) 180 pp.; 30 cm. 6 Sept. 2019 ISBN 978-1-77670-761-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77670-762-1 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2019 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] https://www.mapress.com/j/zt © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 4666 (1) © 2019 Magnolia Press BEHAN-PELLETIER & LINDO Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................4 Introduction ................................................................................................5 -

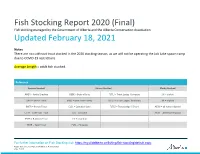

Fish Stocking Report, 2020 (Final)

Fish Stocking Report 2020 (Final) Fish stocking managed by the Government of Alberta and the Alberta Conservation Association Updated February 18, 2021 Notes There are no cutthroat trout stocked in the 2020 stocking season, as we will not be operating the Job Lake spawn camp due to COVID-19 restrictions. Average Length = adult fish stocked. Reference Species Stocked Strains Stocked Ploidy Stocked ARGR = Arctic Grayling BEBE = Beity x Beity TLTLJ = Trout Lodge / Jumpers 2N = diploid BKTR = Brook Trout BRBE = Bow River x Beity TLTLK = Trout Lodge / Kamloops 3N = triploid BNTR = Brown Trout CLCL = Campbell Lake TLTLS = Trout Lodge / Silvers AF2N = all female diploid CTTR = Cutthroat Trout JLJL = Job Lake AF3N = all female triploid RNTR = Rainbow Trout LYLY = Lyndon TGTR = Tiger Trout PLPL = Pit Lakes For further information on Fish Stocking visit: https://mywildalberta.ca/fishing/fish-stocking/default.aspx ©2021 Government of Alberta | Published: February 2021 Page 1 of 24 Waterbody Waterbody ATS Species Strain Genotype Average Number Stocking Official Name Common Name Length Stocked Date (2020) ALFORD LAKE SW4-36-8-W5 RNTR Campbell Lake 3N 18 3000 18-May-20 BEAR POND NW36-14-4-W5 RNTR Trout Lodge/Jumpers AF3N 19.7 750 22-Jun-20 BEAUVAIS LAKE SW29-5-1-W5 RNTR Trout Lodge/Jumpers AF3N 16.3 23000 11-May-20 BEAVER LAKE NE16-35-6-W5 RNTR Trout Lodge/Jumpers AF3N 21.3 2500 21-May-20 BEAVER LAKE NE16-35-6-W5 TGTR Beitty/Bow River 3N 16.9 500 02-Sep-20 BEAVER LAKE NE16-35-6-W5 TGTR Beitty/Bow River 3N 20 500 02-Sep-20 BEAVER MINES LAKE NE11-5-3-W5 -

Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta

Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Submitted to: Submitted by: SSRB Water Storage Opportunities AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Steering Committee a Division of AMEC Americas Limited Lethbridge, Alberta Lethbridge, Alberta 2014 amec.com WATER STORAGE OPPORTUNITIES IN THE SOUTH SASKATCHEWAN RIVER BASIN IN ALBERTA Submitted to: SSRB Water Storage Opportunities Steering Committee Lethbridge, Alberta Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure Lethbridge, Alberta July 2014 CW2154 SSRB Water Storage Opportunities Steering Committee Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin Lethbridge, Alberta July 2014 Executive Summary Water supply in the South Saskatchewan River Basin (SSRB) in Alberta is naturally subject to highly variable flows. Capture and controlled release of surface water runoff is critical in the management of the available water supply. In addition to supply constraints, expanding population, accelerating economic growth and climate change impacts add additional challenges to managing our limited water supply. The South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Water Supply Study (AMEC, 2009) identified re-management of existing reservoirs and the development of additional water storage sites as potential solutions to reduce the risk of water shortages for junior license holders and the aquatic environment. Modelling done as part of that study indicated that surplus water may be available and storage development may reduce deficits. This study is a follow up on the major conclusions of the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Water Supply Study (AMEC, 2009). It addresses the provincial Water for Life goal of “reliable, quality water supplies for a sustainable economy” while respecting interprovincial and international apportionment agreements and other legislative requirements. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Op5 Onlineversion.Cdr

Southern Alberta’s Watersheds: An Overview Occasional Paper Number 5 Acknowledgements: Cover Illustration: Liz Saunders © This report may be cited as: Lalonde, Kim, Corbett, Bill and Bradley, Cheryl. August 2005 Southern Alberta’s Watershed: An Overview Published by Prairie Conservation Forum. Occasional Paper Number 5, 51 pgs. Copies of this report may be obtained from: Prairie Conservation Forum, c/o Alberta Environment, Provincial Building, 200 - 5th Avenue South, Lethbridge, Alberta Canada T1J 4L1 This report is also available online at: http://www.AlbertaPCF.ab.ca Other Occasional Paper in this series are as follows: Gardner, Francis. 1993 The Rules of the World Prairie Conservation Co-ordinating Committee Occasional Paper No. 1, 8 pgs. Bradley, C. and C. Wallis. February 1996 Prairie Ecosystem Management: An Alberta Perspective Prairie Conservation Forum Occasional Paper No. 2, 29 pgs. Dormaar, J.F. And R.L. Barsh. December 2000 The Prairie Landscape: Perceptions of Reality Prairie Conservation Forum Occasional Paper No. 3, 37 pgs. Sinton, H. and C. Pitchford. June 2002 Minimizing the Effects of Oil and Gas Activity on Native Prairie in Alberta Prairie Conservation Forum Occasional Paper No. 4, 40 pgs. Printed on Recycled Paper Prairie Conservation Forum Southern Alberta’s Watersheds: An Overview Kim Lalonde, Bill Corbett and Cheryl Bradley August, 2005 Occasional Paper Number 5 Foreword To fulfill its goal to raise public awareness, disseminate educational materials, promote discussion, and challenge our thinking, the Prairie Conservation Forum (PCF) has launched an Occasional Paper series and a Prairie Notes series. The PCF'sOccasional Paper series is intended to make a substantive contribution to our perception, understanding, and use of the prairie environment - our home. -

Bow River Basin State of the Watershed Summary 2010 Bow River Basin Council Calgary Water Centre Mail Code #333 P.O

30% SW-COC-002397 Bow River Basin State of the Watershed Summary 2010 Bow River Basin Council Calgary Water Centre Mail Code #333 P.O. Box 2100 Station M Calgary, AB Canada T2P 2M5 Street Address: 625 - 25th Ave S.E. Bow River Basin Council Mark Bennett, B.Sc., MPA Executive Director tel: 403.268.4596 fax: 403.254.6931 email: [email protected] Mike Murray, B.Sc. Program Manager tel: 403.268.4597 fax: 403.268.6931 email: [email protected] www.brbc.ab.ca Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 Overview 4 Basin History 6 What is a Watershed? 7 Flora and Fauna 10 State of the Watershed OUR SUB-BASINS 12 Upper Bow River 14 Kananaskis River 16 Ghost River 18 Seebe to Bearspaw 20 Jumpingpound Creek 22 Bearspaw to WID 24 Elbow River 26 Nose Creek 28 WID to Highwood 30 Fish Creek 32 Highwood to Carseland 34 Highwood River 36 Sheep River 38 Carseland to Bassano 40 Bassano to Oldman River CONCLUSION 42 Summary 44 Acknowledgements 1 Overview WELCOME! This State of the Watershed: Summary Booklet OVERVIEW OF THE BOW RIVER BASIN LET’S TAKE A CLOSER LOOK... THE WATER TOWERS was created by the Bow River Basin Council as a companion to The mountainous headwaters of the Bow our new Web-based State of the Watershed (WSOW) tool. This Comprising about 25,000 square kilometres, the Bow River basin The Bow River is approximately 645 kilometres in length. It begins at Bow Lake, at an River basin are often described as the booklet and the WSOW tool is intended to help water managers covers more than 4% of Alberta, and about 23% of the South elevation of 1,920 metres above sea level, then drops 1,180 metres before joining with the water towers of the watershed. -

Biking Trails in the Banff Area

Easy Moderate Difficult Bears And People Plan Ahead and Prepare Banff Road Rides Rules of the Trail The Canadian Rocky Mountain national parks are an 22 19 Golf Course Drive Lake Minnewanka Road 25 Sunshine Road important part of the remaining grizzly and black bear Be a mountain park steward, ride with care! 10.9 km loop 13.1 km loop 8.2 km one way habitat in North America. Even in protected areas, bears Riding non-designated or closed trails, building new trails, or Biking Trails in the Trailhead: Bow Falls parking area Starting Points: Cascade Ponds and Lake Minnewanka day-use area Trailhead: Sunshine Ski Area Road, 7 km west of Banff on the are challenged to avoid people. Think of what it would riding off-trail displaces wildlife and destroys soil and vegetation. Cross the bridge over the Spray River at the end of the parking or the Banff Legacy Trail (21) Trans-Canada Highway be like to be a bear travelling through the mountain These activities are also illegal and violators may be charged area, and you’re off. Perfect for a family outing, this road Lake Minnewanka Road is popular with cyclists and offers a The Sunshine Road begins its steady rise almost immediately, national parks in midsummer – trying to bypass towns, under the National Park Regulations. Banff Area winds gently along the golf course before it loops back. This pleasant ride through varied terrain, with panoramic views and and offers a few steep ramps along the way to its termination campgrounds, highways, railways, and busy trails – and many attractions including Cascade Ponds, Bankhead, Lake is a peaceful road with lovely views over the Bow River and at the ski area parking at the base of the Sunshine gondola. -

Birds of the Kananaskis Forest Experiment Station and Surrounding Area: an Annotated Checklist

BIRDS OF THE KANANASKIS FOREST EXPERIMENT STATION AND SURROUNDING AREA: AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST BY JOHN M. POWELL, TOM S. SADLER AND MARGARET POWELL INFORMATION REPORT NOR-X-133 JUNE, 1975 NORTHERN FOREST RESEARCH CENTRE CANADIAN FORESTRY SERVICE ENVIRONMENT CANADA 5320- 122 STREET EDMONTON, ALBERTA, CANADA T6H 3S5 2 Powell, J.M.I, T. S. Sad1er , and M. Powell. 1975. Birds of the Kananaskis Forest Experiment Station and surrounding area: an annotated checklist. Environ. Can. , For. Serv. , North. For. Res. Cent. Edmonton, Alta. Inf. Rep. NOR-X-133. ABSTRACT The l39 birds observed on the Kananaskis Forest Experiment Station and adjacent Barrier Lake are listed and classified as permanent� winter� or summer residents� or as visitants or migrants. Information is also given on the abundance of each species and whether they are known to breed on the Station. A second list gives the 5l species of birds reported or observed from the adjacent areas which include the Upper Kananaskis River Valley� Stoney Indian Reserve� Sibbald Flats� Moose Mountain� Bow Valley Provincial Park� Seebe� Yamnuska area� and the Bow River Valley westward to Lac des Arcs� Exshaw� and Canmore. A third list of 35 birds indicates species which may probably or possibly be observed in the area since they have been recorded from nearby areas such as Banff or Cochrane. RESUME Les l39 oiseaux observes a la Station experimentale de Kananaskis et a Barrier Lake adjacent sont enumeres et classifies comme permanents� hivernaux� residents d'ete� ou comme visiteurs ou migrateurs. Sont inclus egalement des renseignements sur leur Research Scientist, Northern Forest Research Centre, Canadian Forestry Service, Environment Canada, Edmonton. -

Exploring the Vastness of Banff National Park

Exploring the Vastness of Banff National Park By Claire Walter o borrow on old Ttravelogue cliché, Alberta’s Banff National Park is study in contrast. Its 2,586 square miles comprise both wilderness and civilization. There are high mountains, deep valleys, endless forests and abundant wildlife. Even though much of it feels and looks remote, it is just 70 miles from Calgary – and the Trans-Canada Highway runs right through it. It contains one large town (Banff), one smaller town (Lake Louise Village), two palatial hotels (the Fairmont Banff Springs and Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise) and three significant downhill ski areas (Ski Lake Louise, Sunshine and Norquay). It is a park among parks, with Kootenay National Park just to the south, Yoho National Park to the west (and in another province) and Jasper National Park to the north. It is Canada’s oldest national park and also the one with phenomenal snowshoe opportunities. It’s a great destination for a snowshoe getaway or a multi-activity winter vacation with snowshoeing among the options. There’s skiing (Alpine and Nordic), wildlife viewing, spa- hopping and enjoying the shops, galleries, restaurants and nightspots in Banff or quieter Lake 1 Go FartherTM Model: ARTICA™ BACKCOUNTRY q Two-Piece Articulating Frame q Virtual Pivot Traction Cam q Quick-Cinch™ One-Pull Binding q 80% Recyclable Materials, No PVC’s eastonmountainproducts.com ©2010 easton mountain products Louise Village. As a bonus, winter is low season in Banff, so lodging is a bargain and the shops offer incredible values. Snowshoeing Options The most straightforward snowshoeing is practically from the doorstep of the Chateau Lake Louise.