Bow River Basin State of the Watershed Summary 2010 Bow River Basin Council Calgary Water Centre Mail Code #333 P.O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Trip Guide Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges

1 Field Trip Guide Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges, Foothills, and Great Plains Canadian Society of Soil Science Annual Meeting, Banff, Alberta May 2014 Field trip leaders: Dan Pennock (U. of Saskatchewan) and Paul Sanborn (U. Northern British Columbia) Field Guide Compiled by: Dan and Lea Pennock This Guidebook could be referenced as: Pennock D. and L. Pennock. 2014. Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges, Foothills, and Great Plains. Field Trip Guide. Canadian Society of Soil Science Annual Meeting, Banff, Alberta May 2014. 18 p. 2 3 Banff Park In the fall of 1883, three Canadian Pacific Railway construction workers stumbled across a cave containing hot springs on the eastern slopes of Alberta's Rocky Mountains. From that humble beginning was born Banff National Park, Canada's first national park and the world's third. Spanning 6,641 square kilometres (2,564 square miles) of valleys, mountains, glaciers, forests, meadows and rivers, Banff National Park is one of the world's premier destination spots. In Banff’s early years, The Canadian Pacific Railway built the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise, and attracted tourists through extensive advertising. In the early 20th century, roads were built in Banff, at times by war internees, and through Great Depression-era public works projects. Since the 1960s, park accommodations have been open all year, with annual tourism visits to Banff increasing to over 5 million in the 1990s. Millions more pass through the park on the Trans-Canada Highway. As Banff is one of the world's most visited national parks, the health of its ecosystem has been threatened. -

![New York State Petroleum Business Tax Druwbcamcw^]B M]Q >WPR]Brb](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3637/new-york-state-petroleum-business-tax-druwbcamcw-b-m-q-wpr-brb-113637.webp)

New York State Petroleum Business Tax Druwbcamcw^]B M]Q >WPR]Brb

Publication 532 New York State Petroleum Business Tax DRUWbcaMcW^]bM]Q>WPR]bRb NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TAXATION AND FINANCE PETROLEUM BUSINESS TAX - PUBLICATION 532 PAGE NO. 1 ISSUE DATE 08/09/2021 REGISTRATIONS CANCELLED AND SURRENDERED 02/2021 THRU 08/2021 ALL ASSERTIONS OF RE-INSTATEMENTS OF ANY REGISTRATIONS WHICH HAVE BEEN LISTED AS CANCELLED OR SURRENDERED MUST BE VERIFIED WITH THE TAX DEPARTMENT. ACCORDINGLY, IF ANY DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED TO YOU INDICATING THAT A REGISTRATION HAS BEEN RE-INSTATED, YOU SHOULD CONTACT THE DEPARTMENT'S REGISTRATION AND BOND UNIT AT (518) 591-3089 TO VERIFY THE AUTHENTICITY OF SUCH DOCUMENT. CANCEL COMMERCIAL AVIATION FUEL BUSINESS = A KERO-JET DISTRIBUTOR ONLY = K RETAILER NON-HIGHWAY DIESEL ONLY = R GRID: DIESEL FUEL DISTRIBUTOR = D RESIDUAL PRODUCTS BUSINESS = L TERMINAL OPERATOR = T DIRECT PAY PERMIT - DYED DIESEL = F MOTOR FUEL DISTRIBUTOR = M UTILITIES = U AVIATION GAS RETAIL = G NATURAL GAS = N MCTD MOTOR FUEL WHOLESALERS = W IMPORTING TRANSPORTER = I LIQUID PROPANE = P CANCELLED CANCELLED SURRENDER SURRENDER LEGAL NAME D/B/A NAME CITY ST EIN/TAX ID DATE GRID 37TH AVENUE TRUCKING INC. CORONA NY 113625758 07/15/2021 R ALCUS FUEL OIL, INC. MORICHES NY 113083439 07/15/2021 R ALPINE FUEL INC. EAST ISLIP NY 113180819 07/15/2021 R AMIGOS OIL COMPANY, INC. GREENLAWN NY 274467335 07/15/2021 R ATTIS ETHANOL FULTON, LLC ALPHARETTA GA 832710677 07/26/2021 M T BLY ENERGY SERVICE LLC PETERSBURG NY 811464155 02/21/2021 R BUTTON OIL COMPANY INC MOUNTAIN TOP PA 231654350 02/26/2021 D CRANER OIL COMPANY, INC. -

Bridging the Gap Also Inside

Suburbs Satellites CALGARY & NEIGHBOURING COMMUNITIES& • MAY 2013 Bridging the gap The charm and benefits of small town living near Calgary. Also inside: Spotlight on Southeast Calgary WWW.CALGARYHERALD.COM/SUBS SUBURBSSUBURBS ++ SATELLITESSATELLITES JUNEMAY 20132012 1 everything WE BUILD, WE BUILD around you. Use the power of Baywest’s red pen to make custom changes to your floorplan that suit you. You know there’s a big distinction between “good enough” and “just We build homes from the $400s’ to $1M+ right” and in that gap, exists the opportunity for something better. You wouldn’t think twice about having a suit tailored to fit you, so why compromise on your most important and personal investment? You should expect more. It’s about floorplanning – and inviting you to be a part of that process. Our clients wouldn’t have it any other way. BUILDING IN THESE FINE COMMUNITIES AUBURN BAY SE • RIVERSTONE of CRANSTON SE • MAHOGANY SE • RANCHES OF SILVERADO SW Connect with us: DRESSAGE OF SILVERADO SW • RANCHERS’ RISE in OKOTOKS • NOLAN HILL NW READY-TO-GO | T AILORED | C U S T OM BAYWESTHOMES.COMBAYWESTHOMES.COM 2 SUBURBS + SATELLITES MAY 2013 WWW.CALGARYHERALD.COM/SUBS in this issue Suburbs 2A 21 Airdrie Family moves to Airdrie for house Satellites DIDSBURY CALGARY & NEIGHBOURING COMMUNITIES& • MAY 2013 prices, stays for the schools. 18 Cochrane 582 Historic Bridging the gap The charm and benefits of small downtown CARSTAIRS town living near Calgary. to play a key 4 Chestermere role in the Planners respond to town’s town’s 2 torrid population growth. Also inside: future plans. -

Experience the Icefields Parkway in Winter

EXPLORE! LOOKING FOR ADVENTURE? MORE INFORMATION Winter transforms the Icefields Parkway, one of the world’s most scenic drives. Ancient glaciers glow JASPER INFORMATION CENTRE: 780-852-6176 winter white under blankets of fresh snow. Quiet descends, broken only by far off sounds of ice crevasses growling as LAKE LOUISE VISITOR CENTRE: 403-522-3833 they grow. Snow-covered trails entice drivers to pull over, don snowshoes and break trail below some of the highest VALLEY OF THE FIVE LAKES MODERATE – SNOWSHOES BANFF VISITOR CENTRE: 403-762-1550 mountains in the Canadian Rockies. EXPERIENCE THE 4.5 km loop/2 hrs; 66 m elevation gain/loss pc.gc.ca/jasper Trailhead: 9 km south of Jasper, 224 km north of pc.gc.ca/banff Lake Louise ICEFIELDS LOOKING FOR A QUICK AND WANT TO STRETCH Five small, picturesque lakes in a sunny valley are CHECK THE ROAD CONDITIONS AND THE WEATHER Athabasca Glacier PARKWAY SCENIC STOP? YOUR LEGS? the highlights of this outing, a local family favourite. FORECAST BEFORE YOU LEAVE TOWN: TANGLE FALLS NIGEL PASS ROAD CONDITIONS: Call 511 • alberta511.ca IN WINTER WANT TO STRAP ON MODERATE – SNOWSHOES OR BACKCOUNTRY SKIS Trailhead: 96 km south of Jasper, 137 km north of ATHABASCA FALLS WEATHER FORECAST 14 km/5-6 hrs return; 385 m elevation gain Lake Louise EASY – WEAR STURDY BOOTS SNOWSHOES OR SKIS? Banff 403-762-2088 • Jasper 780-852-3185 This beautiful, cascading icefall right beside the road 1 km/30 mins return; no elevation gain/loss Trailhead: 116 km south of Jasper, 117 km north of weather.gc.ca • Visit an information centre Trailhead: 30 km south of Jasper, 203 km north of makes for a great photo stop. -

Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas

A NATURE ALBERTA CHECKLIST IMPORTANT AND BIRD BIODIVERSITY AREAS IMPORTANT BIRD OF ALBERTA AND BIODIVERSITY AREAS OF ALBERTA NATURE ALBERTA NATURE Use this Checklist as your guide to explore and discover the fascinating natural history and biodiversity of our province. naturealberta.ca A COMMUNITY CONNECTED BY A LOVE OF NATURE The year was 1970. Six nature clubs came together to form the Federation of Alberta Naturalists. More than four decades later, and now known as Nature Alberta, we are grateful for the clubs, the people and the history that has enabled this organization to become the voice for the greater appreciation and conservation of Alberta’s natural environment. We strive to connect Albertans with the natural world that exists all around us. By encouraging Albertans to learn more about and understand natural history and ecological processes, we help ensure that Alberta’s natural heritage and its biodiversity is widely enjoyed, deeply appreciated and thoroughly protected. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Nature Alberta gratefully acknowledges the many individuals and organizations who have contributed to this project. Special thanks to Rob Worona and Margot Hervieux for contributing their time and expertise to reviewing and editing this publication. Thank you also to all of the volunteer IBA Caretakers, past, present and future, who commit to monitoring and stewarding these important natural areas. This project would also not have been possible without the generous support of our partners, including TD Friends of the Environment and Alberta Conservation Association. Cover photo: Yellow-rumped Warbler, D. Godkin Copyright ©2019 Nature Alberta. All rights reserved. SOURCES Information contained within this Checklist has been compiled from the following and other sources as annotated within the publication: BirdLife IBA Important Bird Area Alberta Guide booklet ©2014 Nature Alberta Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas in Canada https://www.ibacanada.org/ Bird Life International website and Data Zone http://www.birdlife.org/ Blue-winged Teal Photo: G. -

2015 Municipal Codes

2015 Municipal Codes Updated December 11, 2015 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2015 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: 0356 - The Town of Chestermere became the City of Chestermere (effective January 1, 2015). NAME CHANGES: 0356 - The City of Chestermere (effective January 1, 2015) from Town of Chestermere. 0506 - Big Lakes County (effective March 6, 2015) from Municipal District of Big Lakes. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0221 – The Village of Minburn dissolved and became part the County of Minburn (effective July 1, 2015). CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0522 Metis Settlements General Council 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (391) 09 Specialized Municipalities (5) 20 Services Commissions (71) 06 Municipal Districts (64) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (107) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (92) 50 Local Government Associations (21) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (5) 08 Special Areas (3) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) December 11, 2015 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. -

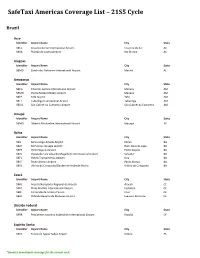

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

Banff to Jasper.Cdr

r r r e e e v v v Lake Louise i i Finish i R R R Ski Area Day 1, Banff to Lake Louise e e e n n Lake Louise n o o o t t 1 t s s s 0 km -Cascade Ponds. Turn LEFT out of the parking area and head Hostel e p i 1 P toward the Hwy 1 interchange. L. Louise Bonnet Ski Area Lipalian Glacier 1a 0.4 -@ the interchange, take the rightside exit ramp onto Hwy 1 Lake Mtn To WEST toward Lake Louise. Louise Castle ke Protection Junction 4.6 -Mt. Norquay interchange, continue on Hwy 1. La e 1A uis Mtn Post Lo 10.1 -Take the exit for Hwy 1A, the Bow Valley Parkway. This is Hotel Sampson 4 Way Lake Louise Finish Mall Stop a quiter road. Campgd 1&2 Lake B 20.9 -Legend has it that the white spruce tree in the middle of the o Louise w road was saved from road construction by the Banff Park 1 R Hostel iv er superintendent in the 1930's. Block Lake 21.1 -Sawback Picnic Area. B C Mtn ow a Louise m p 22.9 -Road splits to go around the toe of the Hillsdale Slide. Chateau g ro Village Lake u n 28.2 -Johnston Canyon on the right. V al Louise d le y 1 29.3 -Moose Meadows. (You seldom see moose here anymore). Mnt Temple 31.5 -This open meadow is the site of a former boom town, Silver Pinnacle Pa rk City. -

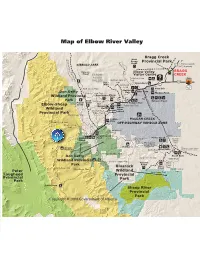

Map of Elbow River Valley

Map of Elbow River Valley ( Bragg Creek T r P a West v o e T l Bragg w Provincial Park n o o d m Creek t to Trans-Canada r e 22 e SIBBALD AREA c S r o n (#1) Highway f o m a w m c e e T n d rail e Trail BRAGG d Canyon Elbow Valley i n Creek w ELBOW Visitor Centre CREEK e t (road) w e a RIVER 758 t Fullerton Loop h e r Sulphur Springs ) VALLEY Trail Ing's Trail 22 Gooseberry 66 Mine Diamond T 40 Loop Ford Creek Trail Allen Bill Station Don Getty Flats River Cove Prairie Creek Trail McLean Pond Powderface Elbow Groups Wildland Provincial Falls Year Winter Round Gate M Gate Winter c Park Trail Gate Groups L McLean Creek Prairie Link e a Prairie Creek Paddy's Flat n Trail C Creek r Elbow-Sheep Winter Gate e Riverview Trail e Beaver k Elbow R Flat o Wildland River a Powderface BeaverLaunch d Provincial Park Ridge Trail 66 Lodge Ford Creek Trail d a o Cobble McLEAN CREEK R Flats s l Nihahi Creek Trail l a F OFF-HIGHWAY VEHICLE ZONE Nihahi Ridge ow lb N TTrail E Wildhorse Trail Winter Forgetmenot Gate Pond Fisher Creek Little Hog's Back Curley Elbow Trail Sands Threepoint Trail Creek Trail Wildhorse to Mount Groups Millarville, Turner Valley, Romulus North ForkMesa Butte Black Diamond, Calgary Winter Trail Gate Threepoint Mtn. Trail 549 Don Getty North Fork Gorge Creek Trail Big 9999 Trail Wildland Provincial Elbow Volcano Ridge Trail Volcano Ware Park Ridge Creek Bluerock Ware Little Elbow Trail Creek Trail Big Elbow Trail Wildland Death Valley Peter Link Creek Trail Trail Lougheed Provincial Provincial Park Park Tombstone Sheep River Provincial Park Copyright © 2008 Government of Alberta. -

Foothills Regional Water and Wastewater Collaborative (Frwwc)

Final Report for: FOOTHILLS REGIONAL WATER AND WASTEWATER COLLABORATIVE (FRWWC) REGIONAL WASTEWATER TREATMENT FEASIBILITY STUDY Date: July 11, 2016 2210-047-00 Proud of Our Past… Building the Future www.mpe.ca Suite 320, 6715 –8 Street NE Calgary, AB T2E 7H7 Phone: 403-250-1362 1-800-351-0929 Fax: 403-250-1518 Foothills Regional Water and Wastewater Collaborative July 11, 2016 c/o Town of Okotoks Municipal Center File: N:\2210\047-00\L02-1.0 5 Elizabeth Street Okotoks, AB T1S 1K1 Attention: Matt Rockley, FRWWC Co-Chair Suzanne Oel, FRWWC Co-Chair Dear Mr. Rockley and Ms. Oel: Re: Regional Wastewater Feasibility Study Final Report We are pleased to submit a final copy of the “Regional Wastewater Feasibility Study” Final Report as requested by the Foothills Regional Water and Wastewater Collaborative (FRWWC). This study is completed in conjunction with Urban Systems Ltd. to provide the FRWWC with an assessment of viable sub-regional alternatives that were beyond that considered in the higher level Calgary Regional Partnership (CRP) work for the South Region. Please contact the undersigned with any questions that you may have. Yours truly, MPE ENGINEERING LTD. Sarah Fratpietro, P.Eng. Project Manager SF/pm Enclosure FRWWC Regional Wastewater Treatment Feasibility Study CORPORATE AUTHORIZATION This report has been prepared by MPE Engineering Ltd. and Urban Systems Ltd. under authorization of Foothills Regional Water and Wastewater Collaborative. The material in this report represents the best judgment of MPE Engineering Ltd. and Urban Systems Ltd. given the available information. Any use that a third party makes of this report, or reliance on or decisions made based upon it is the responsibility of the third party. -

RURAL ECONOMY Ciecnmiiuationofsiishiaig Activity Uthern All

RURAL ECONOMY ciEcnmiIuationofsIishiaig Activity uthern All W Adamowicz, P. BoxaIl, D. Watson and T PLtcrs I I Project Report 92-01 PROJECT REPORT Departmnt of Rural [conom F It R \ ,r u1tur o A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta W. Adamowicz, P. Boxall, D. Watson and T. Peters Project Report 92-01 The authors are Associate Professor, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton; Forest Economist, Forestry Canada, Edmonton; Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton and Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton. A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta Interim Project Report INTROI)UCTION Recreational fishing is one of the most important recreational activities in Alberta. The report on Sports Fishing in Alberta, 1985, states that over 340,000 angling licences were purchased in the province and the total population of anglers exceeded 430,000. Approximately 5.4 million angler days were spent in Alberta and over $130 million was spent on fishing related activities. Clearly, sportsfishing is an important recreational activity and the fishery resource is the source of significant social benefits. A National Angler Survey is conducted every five years. However, the results of this survey are broad and aggregate in nature insofar that they do not address issues about specific sites. It is the purpose of this study to examine in detail the characteristics of anglers, and angling site choices, in the Southern region of Alberta. Fish and Wildlife agencies have collected considerable amounts of bio-physical information on fish habitat, water quality, biology and ecology.