Tracing Aspects of the Greek Crisis in Athens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION Tel.: 2103202049, Fax: 2103226371

LIST OF BANK BRANCHES (BY HEBIC) 30/06/2015 BANK OF GREECE HEBIC BRANCH NAME AREA ADDRESS TELEPHONE NUMBER / FAX 0100001 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARIAT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202049, fax: 2103226371 0100002 HEAD OFFICE TENDER AND ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS PROCUREMENT SECTION tel.: 2103203473, fax: 2103231691 0100003 HEAD OFFICE HUMAN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS RESOURCES SECTION tel.: 2103202090, fax: 2103203961 0100004 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202198, fax: 2103236954 0100005 HEAD OFFICE PAYROLL ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202096, fax: 2103236930 0100007 HEAD OFFICE SECURITY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202101, fax: 210 3204059 0100008 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION A tel.: 2103205154, fax: …… 0100009 HEAD OFFICE BOOK ENTRY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202620, fax: 2103235747 0100010 HEAD OFFICE ARCHIVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202206, fax: 2103203950 0100012 HEAD OFFICE RESERVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT BACK UP SECTION tel.: 2103203766, fax: 2103220140 0100013 HEAD OFFICE FOREIGN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS SECTION tel.: 2103202895, fax: 2103236746 0100014 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION B tel.: 2103205041, fax: …… 0100015 HEAD OFFICE PAYMENT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS SYSTEMS OVERSIGHT SECTION tel.: 2103205073, fax: …… 0100016 HEAD OFFICE ESCB PROJECTS CHALANDRI 341, Mesogeion Ave., 152 31 CHALANDRI AUDIT SECTION tel.: 2106799743, fax: 2106799713 0100017 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENTARY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece

CHAPTER 10 Commoning Over a Cup of Coffee: The Case of Kafeneio, a Co-op Cafe at Plato’s Academy Chrysostomos Galanos The story of Kafeneio Kafeneio, a co-op cafe at Plato’s Academy in Athens, was founded on the 1st of May 2010. The opening day was combined with an open, self-organised gather- ing that emphasised the need to reclaim open public spaces for the people. It is important to note that every turning point in the life of Kafeneio was somehow linked to a large gathering. Indeed, the very start of the initiative, in September 2009, took the form of an alternative festival which we named ‘Point Defect’. In order to understand the choice of ‘Point Defect’ as the name for the launch party, one need only look at the press release we made at the time: ‘When we have a perfect crystal, all atoms are positioned exactly at the points they should be, for the crystal to be intact; in the molecular structure of this crystal everything seems aligned. It can be, however, that one of the atoms is not at place or missing, or another type of atom is at its place. In that case we say that the crystal has a ‘point defect’, a point where its struc- ture is not perfect, a point from which the crystal could start collapsing’. How to cite this book chapter: Galanos, C. 2020. Commoning Over a Cup of Coffee: The Case of Kafeneio, a Co-op Cafe at Plato’s Academy. In Lekakis, S. (ed.) Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece. -

Athens Strikes & Protests Survival Guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the Crisis Day Trip Delphi, the Navel of the World Ski Around Athens Yes You Can!

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps ATHENS Strikes & Protests Survival guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the crisis Day trip Delphi, the Navel of the world Ski around Athens Yes you can! N°21 - €2 inyourpocket.com CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents The Basics Facts, habits, attitudes 6 History A few thousand years in two pages 10 Districts of Athens Be seen in the right places 12 Budget Athens What crisis? 14 Strikes & Protests A survival guide 15 Day trip Antique shop Spend a day at the Navel of the world 16 Dining & Nightlife Ski time Restaurants Best resorts around Athens 17 How to avoid eating like a ‘tourist’ 23 Cafés Where to stay Join the ‘frappé’ nation 28 5* or hostels, the best is here for you 18 Nightlife One of the main reasons you’re here! 30 Gay Athens 34 Sightseeing Monuments and Archaeological Sites 36 Acropolis Museum 40 Museums 42 Historic Buildings 46 Getting Around Airplanes, boats and trains 49 Shopping 53 Directory 56 Maps & Index Metro map 59 City map 60 Index 66 A pleasant but rare Athenian view athens.inyourpocket.com Winter 2011 - 2012 4 FOREWORD ARRIVING IN ATHENS he financial avalanche that started two years ago Tfrom Greece and has now spread all over Europe, Europe In Your Pocket has left the country and its citizens on their knees. The population has already gone through the stages of denial and anger and is slowly coming to terms with the idea that their life is never going to be the same again. -

View Fact Sheet

WELCOME In the heart of the city, Wyndham Athens Residence oers luxury accommodation and great connectivity. The brand-new accommodations are indeed an extension of the elegant Wyndham Grand Athens and will fasci- nate you with their discreet lavishness and exceptional comfort. L OCATION The Wyndham Athens Residence is conveniently located in the commercial and business district of the city right next to metro station. It oers the ideal starting point to explore some of the major archaeological sites of Athens, the most important museums and significant landmarks within min- utes. Acropolis & Acropolis museum are within 15 to 20 min- utes walking distance from the hotel and the airport is just a 40’ minutes’ drive. SIGHTS • Acropolis & Acropolis Museum 1.53 km • Karytsi & St. Eirini squares with famous nightlife 1.5 km • National Archaeological Museum 1.05 km • Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre 5.6 km • Benaki Museum 2 km • Athens Riviera, the coastal area of Attica 10 km • Cycladic art museum 2.5 km • Monastiraki & Flea Market 1 km FACILITIES • Plaka the historical neighborhood of Athens 3 km • Thisseio for nightlife 1.3 km • 89 rooms & suites • Temple of Olympian Zeus 2 km • Gym • Varvakeios agora – the central market of Athens 1km • Roof Top Bar Restaurant • Ermou Shopping Street 1.53 km • Spa (at the neighboring Wyndham Grand Athens) • National Garden 1.8 km • Car parking on site (at the neighboring Wyndham Grand Athens) SERVICES • 24 hours Reception • Doctor on call* • Concierge Service • Private parking* • 24 hours Room -

Hotel Athens Imperial

2-6 M. Alexandrou, Karaiskaki str., 104 37, Athens Metro Station Metaxourgeio Tel.: +30 210 52 01 600, Fax: +30 210 52 25 524 • e-mail: [email protected] www.classicalhotels.com Classical Athens Imperial Rooms & Amenities Distinctive and welcoming, the Classical rectly to Karaiskaki Square. area in open plan style. Elegantly deco- Athens Imperial is one of the city’s most rated, and with marble bathroom with stylish and vibrant hotels. Its monumen- GUEST ROOMS & SUITES separate shower cabin and exclusive tal facade ushers guests into a tastefully The Classical Athens Imperial has a to- luxury guest amenities. All Junior Suites furnished and arty interior that combines tal of 261 rooms including 25 suites. All offer King Beds. contemporary decoration with timeless guestrooms are equipped with individu- elegance. Its state-of-art business facili- ally controlled air-conditioning, work- Corner Junior Suites: ties can transform guest rooms into an ing desk, refrigerated private maxi-bar, office and host conferences and meet- in room safe, satellite TV with 24-hour ings for up to 1,400 people, while the 7th movie channel, coffee making facilities, floor has been tailored to the needs of direct dial telephone, High-Speed Inter- discerning business executives. Over- net Access and voicemail. The marbled look the city from the roof garden, facing bathrooms accompanied by lavish vani- the Parthenon and enjoying a cocktail by ties and makeup/shaving mirror; most the pool. have separate shower cabin and feature fine personal-care items, hair dryers, slippers and terry bathrobes. Additional- Located on building’s corner on all ly, all suites and deluxe rooms on the 7th floors, and with approximately 50 square floor are equipped with iron, iron-board meters of space they consist of a spa- and coffee-machine. -

Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece

Stelios Lekakis Stelios Lekakis Edited by Edited by CulturalCultural heritageheritage waswas inventedinvented inin thethe realmrealm ofof nation-states,nation-states, andand fromfrom EditedEdited byby anan earlyearly pointpoint itit waswas consideredconsidered aa publicpublic good,good, stewardedstewarded toto narratenarrate thethe SteliosStelios LekakisLekakis historichistoric deedsdeeds ofof thethe ancestors,ancestors, onon behalfbehalf ofof theirtheir descendants.descendants. NowaNowa-- days,days, asas thethe neoliberalneoliberal rhetoricrhetoric wouldwould havehave it,it, itit isis forfor thethe benefitbenefit ofof thesethese tax-payingtax-paying citizenscitizens thatthat privatisationprivatisation logiclogic thrivesthrives inin thethe heritageheritage sector,sector, toto covercover theirtheir needsneeds inin thethe namename ofof socialsocial responsibilityresponsibility andand otherother truntrun-- catedcated viewsviews ofof thethe welfarewelfare state.state. WeWe areare nownow atat aa criticalcritical stage,stage, wherewhere thisthis doubledouble enclosureenclosure ofof thethe pastpast endangersendangers monuments,monuments, thinsthins outout theirtheir socialsocial significancesignificance andand manipulatesmanipulates theirtheir valuesvalues inin favourfavour ofof economisticeconomistic horizons.horizons. Conversations on the Case of Greece Conversations on the Case of Greece Cultural Heritage in the Realm of Commons: Cultural Heritage in the Realm of Commons: ThisThis volumevolume examinesexamines whetherwhether wewe cancan placeplace -

Planning Development of Kerameikos up to 35 International Competition 1 Historical and Urban Planning Development of Kerameikos

INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION FOR ARCHITECTS UP TO STUDENT HOUSING 35 HISTORICAL AND URBAN PLANNING DEVELOPMENT OF KERAMEIKOS UP TO 35 INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION 1 HISTORICAL AND URBAN PLANNING DEVELOPMENT OF KERAMEIKOS CONTENTS EARLY ANTIQUITY ......................................................................................................................... p.2-3 CLASSICAL ERA (478-338 BC) .................................................................................................. p.4-5 The municipality of Kerameis POST ANTIQUITY ........................................................................................................................... p.6-7 MIDDLE AGES ................................................................................................................................ p.8-9 RECENT YEARS ........................................................................................................................ p.10-22 A. From the establishment of Athens as capital city of the neo-Greek state until the end of 19th century. I. The first maps of Athens and the urban planning development II. The district of Metaxourgeion • Inclusion of the area in the plan of Kleanthis-Schaubert • The effect of the proposition of Klenze regarding the construction of the palace in Kerameikos • Consequences of the transfer of the palace to Syntagma square • The silk mill factory and the industrialization of the area • The crystallization of the mixed suburban character of the district B. 20th century I. The reformation projects -

Freedom of Assembly at Risk and Unlawful Use of Force in the Era of Covid-19

GREECE: FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY AT RISK AND UNLAWFUL USE OF FORCE IN THE ERA OF COVID-19 Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Cover photo: Police stands guard in front of the Greeek parliament on the sidelines of a demonstration Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons to support ailing Greek far-left hitman Dimitris Koufodinas in Athens on March 2, 2021. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © LOUISA GOULIAMAKI/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: EUR 25/4399/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 2. INTRODUCTION 6 3. METHODOLOGY 7 4. LAW AND GUIDELINES REGULATING DEMONSTRATIONS BREACH INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS 8 4.1 DISPERSAL OF ASSEMBLIES 9 4.1.1 MANDATORY NOTIFICATION REQUIREMENTS 10 4.1.2 REGULATION OF SPONTANEOUS ASSEMBLIES 10 4.1.3 USE OF FORCE IN THE DISPERSAL OF AN ASSEMBLY 11 4.2 PROHIBITION OF ASSEMBLIES 11 4.2.1 LAW 4703/2020 11 4.2.2 BLANKET BANS ON ASSEMBLIES: A BLATANT VIOLATION OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY 12 4.3 USE OF SURVEILLANCE SYSTEMS 14 4.4 IDENTIFICATION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICIALS 15 5. -

Response of the Government of Greece to the Report of The

CPT/Inf (2002) 32 Response of the Government of Greece to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Greece from 23 September to 5 October 2001 The Government of Greece has requested the publication of the CPT's report on the Committee's visit to Greece in September/October 2001 (see CPT/Inf (2002) 31) and of its response. The response of the Government of Greece is set out in this document. Strasbourg, 20 November 2002 Response of the Government of Greece to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Greece from 23 September to 5 October 2001 - 3 - CONTENTS MINISTRY OF PUBLIC ORDER ……………………………………….. 5 MINISTRY OF JUSTICE ………………………………………………… 39 MINISTRY OF NATIONAL DEFENCE ………………………………… 51 MINISTRY OF MERCHANT MARINE ………………………………… 53 MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND WELFARE ……………………………. 55 - 5 - MINISTRY OF PUBLIC ORDER GREEK POLICE HEADQUARTERS SECURITY AND ORDER BRANCH DIRECTORATE OF ALIENS R E P O R T On the observations drawn up by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment ATHENS SEPTEMBER 2002 - 7 - CONTENTS PAGE A. INTRODUCTION 9 B. RESPONSES ON THE OBSERVATIONS DRAWN UP BY THE COMMITTEE, AS THE SAME ARE INCLUDED IN APPENDIX I TO ITS REPORT 10 1. PHYSICAL ILL-TREATMENT OF DETAINEES 10 i. Legal texts prescribing sanctions to be imposed on law enforcement officers in case of physical abuse of detainees 10 ii. Measures for the elimination of the phenomenon of violence exercised by police officers against citizens 12 iii.Training of Police Officers in relation to human rights 13 Innovations introduced in Police Officers' School 13 Innovations introduced in Police Constables' School 14 Innovations introduced in the school of retraining and refresher training 15 Innovations introduced in the School of National Security 16 iv. -

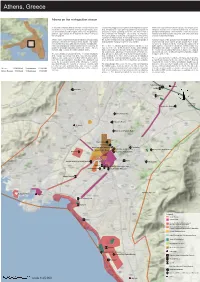

Athens on the Metropolitan Stream

Athens, Greece Athens on the metropolitan stream In the public imaginary Athens has both a famous and an infa- Greece’s housing production system (small fragmented owner- frastructure improvements (Attica highway, new airport, public mous identity. A city immersed in history and philosophy, as lo- ship, self-promotion, loose planning system etc) along with the transport, reconstruction of central squares etc), but also the cus of social and political struggles, famous for its high density, promotion of home ownership (since the 50s) and the role of pretext for wasting many “urban reserves” (urban land or public pollution, ugly buildings and a -depicted as chaotic- metropoli- family networks, has managed - until recently - to respond to infrastructure) and economic resources over other urban and/ tan everyday life. the housing needs of locals and to incorporate the newcomers. or social investments needed. However we might foresee an emerging housing crisis, since Athens is also a well-known tourist destination, though mostly the number of homeless and inadequately housed people is A positive legacy of the Olympics was the proliferation of local visited as a transit to the famous Greek islands. Few visitors soaring and the mortgage market is very unstable. movements and active citizens groups around issues of pub- come to Athens to stay (although this might be changing since lic, open, green spaces and the environmental awareness of it has gained popularity among tourists from the Balkans). Its Greece has a centralized planning system and this is even public opinion, very much needed in an environmentally very peripheral geographical position, but also the intense, not very more so in the case of Athens (given its size and centrality). -

Divercities-City Book-Athens.Pdf

DIVERCITIES Governing Urban Diversity: governing urban diversity Creating Social Cohesion, Social Mobility and Economic Performance in Today’s Hyper-diversified Cities Dealing with Urban Diversity Dealing with Urban Diversity This book is one of the outcomes of the DIVERCITIES project. It focuses on the question of how to create social cohesion, social • mobility and economic performance in today’s hyper-diversified cities. The Case of Athens The Case of Athens The project’s central hypothesis is that urban diversity is an asset; it can inspire creativity, innovation and make cities more liveable. Georgia Alexandri There are fourteen books in this series: Antwerp, Athens, Dimitris Balampanidis Nicos Souliotis Budapest, Copenhagen, Istanbul, Leipzig, London, Milan, Thomas Maloutas Paris, Rotterdam, Tallinn, Toronto, Warsaw and Zurich. George Kandylis This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under www.urbandivercities.eu grant agreement No. 319970. SSH.2012.2.2.2-1; Governance of cohesion and diversity in urban contexts. DIVERCITIES: Dealing with Urban Diversity The Case of Athens Georgia Alexandri Dimitris Balampanidis Nicos Souliotis Thomas Maloutas George Kandylis Governing Urban Diversity: Creating Social Cohesion, Social Mobility and Economic Performance in Today’s Hyper-diversified Cities To be cited as: Alexandri, G., D. Balampanidis, Lead Partner N. Souliotis, T. Maloutas and G. Kandylis (2017). - Utrecht University, The Netherlands DIVERCITIES: Dealing with Urban Diversity – The case of Athens. Athens: EKKE. Consortium Partners - University of Vienna, Austria This report has been put together by the authors, - University of Antwerp, Belgium and revised on the basis of the valuable comments, - Aalborg University, Denmark suggestions, and contributions of all DIVERCITIES - University of Tartu, Estonia partners.