Comparative Genomics and Association Analysis Identifies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educated Youth Should Go to the Rural Areas: a Tale of Education, Employment and Social Values*

Educated Youth Should Go to the Rural Areas: A Tale of Education, Employment and Social Values* Yang You† Harvard University This draft: July 2018 Abstract I use a quasi-random urban-dweller allocation in rural areas during Mao’s Mass Rustication Movement to identify human capital externalities in education, employment, and social values. First, rural residents acquired an additional 0.1-0.2 years of education from a 1% increase in the density of sent-down youth measured by the number of sent-down youth in 1969 over the population size in 1982. Second, as economic outcomes, people educated during the rustication period suffered from less non-agricultural employment in 1990. Conversely, in 2000, they enjoyed increased hiring in all non-agricultural occupations and lower unemployment. Third, sent-down youth changed the social values of rural residents who reported higher levels of trust, enhanced subjective well-being, altered trust from traditional Chinese medicine to Western medicine, and shifted job attitudes from objective cognitive assessments to affective job satisfaction. To explore the mechanism, I document that sent-down youth served as rural teachers with two new county-level datasets. Keywords: Human Capital Externality, Sent-down Youth, Rural Educational Development, Employment Dynamics, Social Values, Culture JEL: A13, N95, O15, I31, I25, I26 * This paper was previously titled and circulated, “Does living near urban dwellers make you smarter” in 2017 and “The golden era of Chinese rural education: evidence from Mao’s Mass Rustication Movement 1968-1980” in 2015. I am grateful to Richard Freeman, Edward Glaeser, Claudia Goldin, Wei Huang, Lawrence Katz, Lingsheng Meng, Nathan Nunn, Min Ouyang, Andrei Shleifer, and participants at the Harvard Economic History Lunch Seminar, Harvard Development Economics Lunch Seminar, and Harvard China Economy Seminar, for their helpful comments. -

Research on Employment Difficulties and the Reasons of Typical

2017 3rd International Conference on Education and Social Development (ICESD 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-444-8 Research on Employment Difficulties and the Reasons of Typical Resource-Exhausted Cities in Heilongjiang Province during the Economic Transition Wei-Wei KONG1,a,* 1School of Public Finance and Administration, Harbin University of Commerce, Harbin, China [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: Typical Resource-Exhausted Cities, Economic Transition, Employment. Abstract. The highly correlation between the development and resources incurs the serious problems of employment during the economic transition, such as greater re-employment population, lower elasticity of employment, greater unemployed workers in coal industry. These problems not only hinder the social stability, but also slow the economic transition and industries updating process. We hope to push forward the economic transition of resource-based cities and therefore solve the employment problems through the following measures: developing specific modern agriculture and modern service industry, encouraging and supporting entrepreneurships, implementing re-employment trainings, strengthening the public services systems for SMEs etc. Background According to the latest statistics from the State Council for 2013, there exists 239 resource-based cities in China, including 31 growing resource-based cities, 141 mature, and 67 exhausted. In the process of economic reform, resource-based cities face a series of development challenges. In December 2007, the State Council issued the Opinions on Promoting the Sustainable Development of Resource-Based Cities. The National Development and Reform Commission identified 44 resource-exhausted cities from March 2008 to March 2009, supporting them with capital, financial policy and financial transfer payment funds. In the year of 2011, the National Twelfth Five-Year Plan proposed to promote the transformation and development of resource-exhausted area. -

![Review Statement of World Biosphere Reserve [ July 2013 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2831/review-statement-of-world-biosphere-reserve-july-2013-72831.webp)

Review Statement of World Biosphere Reserve [ July 2013 ]

Review Statement of World Biosphere Reserve [ July 2013 ] Prefeace According to the Resolution 28 C/2.4 on Statutory Framework of MAB (Man and Biosphere) Program passed on the 28th session of the UNESCO General Conference, Article 4 has been clearly identified as the criteria which shall be followed by biosphere reserves. In addition, it is stipulated in Article 9 that a Decennium Review shall be conducted on the world biosphere reserve every a decade, this Review shall be based on the report prepared by the relevant authority; the Review result shall be submitted to the relevant national secretariat. The related text of Statutory Framework is attached in Annex 3. This Review Statement will be helpful for each country preparing national reports and update data as stipulated in Article 9, and the secretariat timely accessing to data associated with the biosphere reserve. This Statement shall contribute to the inspection of MAB ICC on the biosphere reserve, and judge whether it can meet all criteria mentioned in Article 9 of the Legal Framework, especially three major functions. It shall be noted that is required to specify how the biosphere reserve achieves the various criteria in the last part of the Statement (Criteria and Progress). The information from Decennium Review will be used by UNESCO for the following purposes: (a) Inspection of the relevant autorities of International Advisory Committee and MAB ICC on the biosphere reserve; and (b) the world's information system, especially the UNESCO's MAB network and publications, so as to promote communication among people concerned the world biosphere reserve and influence each other. -

Optimization Path of the Freight Channel of Heilongjiang Province

2017 3rd International Conference on Education and Social Development (ICESD 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-444-8 Optimization Path of the Freight Channel of Heilongjiang Province to Russia 1,a,* 2,b Jin-Ping ZHANG , Jia-Yi YUAN 1Harbin University of Commerce, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China 2International Department of Harbin No.9 High School, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China [email protected], [email protected] * Corresponding author Keywords: Heilongjiang Province, Russia, Freight Channel, Optimization Path. Abstract. Heilongjiang Province becomes the most important province for China's import and export trade to Russia due to its unique geographical advantages and strong complementary between industry and product structure. However, the existing problems in the trade freight channel layout and traffic capacity restrict the bilateral trade scale expansion and trade efficiency improvement. Therefore, the government should engage in rational distribution of cross-border trade channel, strengthen infrastructure construction in the border port cities and node cities, and improve the software support and the quality of service on the basis of full communication and coordination with the relevant Russian government, which may contribute to upgrade bilateral economic and trade cooperation. Introduction Heilongjiang Province is irreplaceable in China's trade with Russia because of its geographical advantages, a long history of economic and trade cooperation, and complementary in industry and product structures. Its total value of import and export trade to Russia account for more than 2/3 of the whole provinces and nearly 1/4 of that of China. After years of efforts, there exist both improvement in channel infrastructure, layout and docking and problems in channel size, functional positioning and layout, as well as important node construction which do not match with cross-border freight development. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Spatiotemporal Changes of Reference Evapotranspiration in the Highest-Latitude Region of China

Article Spatiotemporal Changes of Reference Evapotranspiration in the Highest-Latitude Region of China Peng Qi 1,2, Guangxin Zhang 1,*, Y. Jun Xu 3, Yanfeng Wu 1,2 and Zongting Gao 4 1 Key Laboratory of Wetland Ecology and Environment, Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 4888, Shengbei Street, Changchun 130102, China; [email protected] (P.Q.); [email protected] (Y.W.) 2 University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 School of Renewable Natural Resources, Louisiana State University Agricultural Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA; [email protected] 4 Institute of Meteorological Sciences of Jilin Province, and Laboratory of Research for Middle-High Latitude Circulation and East Asian Monsoon, and Jilin Province Key Laboratory for Changbai Mountain Meteorology and Climate Change, Changchun 130062, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-431-8554-2210; Fax: +86-431-8554-2298 Received: 2 June 2017; Accepted: 4 July 2017; Published: 5 July 2017 Abstract: Reference evapotranspiration (ET0) is often used to make management decisions for crop irrigation scheduling and production. In this study, the spatial and temporal trends of ET0 in China’s most northern province as well as the country’s largest agricultural region were analyzed for the period from 1964 to 2013. ET0 was calculated with the Penman-Monteith of Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations irrigation and drainage paper NO.56 (FAO-56) using climatic data collected from 27 stations. Inverse distance weighting (IDW) was used for the spatial interpolation of the estimated ET0. A Modified Mann–Kendall test (MMK) was applied to test the spatiotemporal trends of ET0, while Pearson’s correlation coefficient and cross-wavelet analysis were employed to assess the factors affecting the spatiotemporal variability at different elevations. -

December 1998

JANUARY - DECEMBER 1998 SOURCE OF REPORT DATE PLACE NAME ALLEGED DS EX 2y OTHER INFORMATION CRIME Hubei Daily (?) 16/02/98 04/01/98 Xiangfan C Si Liyong (34 yrs) E 1 Sentenced to death by the Xiangfan City Hubei P Intermediate People’s Court for the embezzlement of 1,700,00 Yuan (US$20,481,9). Yunnan Police news 06/01/98 Chongqing M Zhang Weijin M 1 1 Sentenced by Chongqing No. 1 Intermediate 31/03/98 People’s Court. It was reported that Zhang Sichuan Legal News Weijin murdered his wife’s lover and one of 08/05/98 the lover’s relatives. Shenzhen Legal Daily 07/01/98 Taizhou C Zhang Yu (25 yrs, teacher) M 1 Zhang Yu was convicted of the murder of his 01/01/99 Zhejiang P girlfriend by the Taizhou City Intermediate People’s Court. It was reported that he had planned to kill both himself and his girlfriend but that the police had intervened before he could kill himself. Law Periodical 19/03/98 07/01/98 Harbin C Jing Anyi (52 yrs, retired F 1 He was reported to have defrauded some 2600 Liaoshen Evening News or 08/01/98 Heilongjiang P teacher) people out of 39 million Yuan 16/03/98 (US$4,698,795), in that he loaned money at Police Weekend News high rates of interest (20%-60% per annum). 09/07/98 Southern Daily 09/01/98 08/01/98 Puning C Shen Guangyu D, G 1 1 Convicted of the murder of three children - Guangdong P Lin Leshan (f) M 1 1 reported to have put rat poison in sugar and 8 unnamed Us 8 8 oatmeal and fed it to the three children of a man with whom she had a property dispute. -

The Impact of Continuous Driving Time and Rest Time on Commercial Drivers' Driving Performance and Recovery

Journal of Safety Research 50 (2014) 11–15 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Safety Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsr The impact of continuous driving time and rest time on commercial drivers' driving performance and recovery Lianzhen Wang a,⁎,YulongPeib a School of Transportation Science and Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150090, China b Traffic College, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China article info abstract Article history: Problem: This real road driving study was conducted to investigate the effects of driving time and rest time on the Received 16 March 2013 driving performance and recovery of commercial coach drivers. Methods: Thirty-three commercial coach drivers Received in revised form 11 January 2014 participated in the study, and were divided into three groups according to driving time: (a) 2 h, (b) 3 h, and (c) 4 Accepted 15 January 2014 h. The Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS) was used to assess the subjective fatigue level of the drivers. One-way Available online 28 January 2014 ANOVA was employed to analyze the variation in driving performance. Results: The statistical analysis revealed that driving time had a significant effect on the subjective fatigue and driving performance measures among Keywords: the three groups. After 2 h of driving, both the subjective fatigue and driving performance measures began to de- Fatigue driving fi Driving performance teriorate. After 4 h of driving, all of the driving performance indicators changed signi cantly except for depth per- Commercial coach drivers ception. A certain amount of rest time eliminated the negative effects of fatigue. A 15-minute rest allowed drivers Driving time to recover from a two-hour driving task. -

Download From

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8 th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9 th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY . DD MM YY Name: Shoubin Cui Institution: Bureau of Heilongjiang Qixing River National Nature Reserve Address: 5 Yongfa Road, Baoqing County 155600, Designation date Site Reference Number Heilongjiang Province, China Tel: +86-(0)469-5417409 Fax: +86-(0)469-5200003 E-mail:[email protected] 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: August 25, 2011 3. -

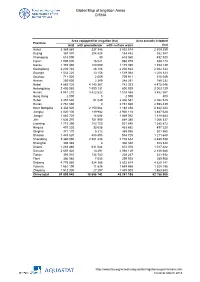

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Heilongjiang Road Development II Project (Yichun-Nenjiang)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: TA 7117 – PRC October 2009 People’s Republic of China: Heilongjiang Road Development II Project (Yichun-Nenjiang) FINAL REPORT (Volume II of IV) Submitted by: H & J, INC. Beijing International Center, Tower 3, Suite 1707, Beijing 100026 US Headquarters: 6265 Sheridan Drive, Suite 212, Buffalo, NY 14221 In association with WINLOT No 11 An Wai Avenue, Huafu Garden B-503, Beijing 100011 This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. All views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Asian Development Bank Heilongjiang Road Development II (TA 7117 – PRC) Final Report Supplementary Appendix A Financial Analysis and Projections_SF1 S App A - 1 Heilongjiang Road Development II (TA 7117 – PRC) Final Report SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX SF1 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS AND PROJECTIONS A. Introduction 1. Financial projections and analysis have been prepared in accordance with the 2005 edition of the Guidelines for the Financial Governance and Management of Investment Projects Financed by the Asian Development Bank. The Guidelines cover both revenue earning and non revenue earning projects. Project roads include expressways, Class I and Class II roads. All will be built by the Heilongjiang Provincial Communications Department (HPCD). When the project started it was assumed that all project roads would be revenue earning. It was then discovered that national guidance was that Class 2 roads should be toll free. The ADB agreed that the DFR should concentrate on the revenue earning Expressway and Class I roads, 2. -

Strategic Priorities of Cooperation Between Heilongjiang Province and Russia L

R-ECONOMY, 2019, 5(1), 13–18 doi: 10.15826/recon.2019.5.1.002 Original Paper doi 10.15826/recon.2019.5.1.002 Strategic priorities of cooperation between Heilongjiang province and Russia L. Song Institute of Northeast Asian Studies, Heilongjiang Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, Harbin, China; e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS During the five-year period of implementation of the Belt and Road Initia- Belt and Road Initiative; tive, Heilongjiang Province, which is one of the nine Chinese border provinc- Heilongjiang Province; Eastern es, has actively responded to the national development policy and achieved Silk Road Belt; Longjiang Silk some impressive results in its strategic cooperation with the Russian Far Road Belt; strategic planning; East. The article characterizes the current state of Heilongjiang Province’s re- cooperation lationship with Russia and describes its strategic plans for findings new paths of cooperation as a result of the province’s integration into the Belt and Road ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Initiative and participation in China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor Heilongjiang Province, the special construction. The key projects crucial for the province’s development are the subject of the 12th Fourth Plenary Eastern Land-Sea Silk Road Economic Belt (hereinafter referred to as the Session of “Research on the Eastern Silk Road Belt) and the Heilongjiang Land-Sea Silk Road Economic Construction of New Pattern Belt (hereinafter referred to as Longjiang Silk Road Belt). Both projects are of All-dimensional Opening up aimed at increasing the interconnectedness between regions and countries, in Heilongjiang Province”, promoting international trade and fostering understanding and tolerance.