Carte Italiane, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pages 4 Rotella, Lot 51 Pagine

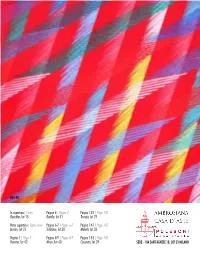

LOT 42 In copertina | Cover Pagine 4 | Pages 4 Pagina 133 | Page 133 Baechler, lot 15 Rotella, lot 51 Turcato, lot 29 Retro copertina | Back cover Pagine 6-7 | Pages 6-7 Pagina 142 | Page 142 Arman, lot 25 Schifano, lot 30 Melotti, lot 33 Pagina 1 | Page 1 Pagine 8-9 | Pages 8-9 Pagina 143 | Page 143 Dorazio, lot 42 Music, lot 60 Cassinari, lot 39 SEDE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18, 20123 MILANO ASTA ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 – presso LA POSTERIA 23 OTTOBRE - 4 NOVEMBRE, MILANO VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 0 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00 – ESCLUSO FESTIVI E 29 OTTOBRE) PREVIO APPUNTAMENTO 7-8-9 NOVEMBRE, MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00) UNICA SESSIONE MARTEDÌ 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 16.00 LOTTI 1 - 243 PRESENTAZIONE TELEVISIVA TOP LOTS Lunedì 2/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Martedì 3/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Giovedì 5/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Venerdì 6/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre OFFERTE SCRITTE FINO A LUNEDÌ 9 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 15.00 FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] È possibile partecipare in diretta on-line inscrivendosi (almeno 24 ore prima) sul nostro sito www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CONSULTAZIONE CATALOGO E MODULISTICA www.ambrosianacasadaste.com da venerdì 23 ottobre 2020 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. +39 0289459708 - FAX +39 0240703717 www.ambrosianacasadaste.com • [email protected] LOT 51 338 1226703 5 MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART -

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

Carla Accardi Biography

SPERONE WESTWATER 257 Bowery New York 10002 T + 1 212 999 7337 F + 1 212 999 7338 www.speronewestwater.com Carla Accardi Biography 1924 Born Trapani, Sicily 2014 Died Rome, Italy One Person Exhibitions: 1950 “Carla Accardi. 15 Tempere,” Galleria Age d’Or, Rome, 16 November – 1 December 1951 “Accardi e Sanfilippo,” Libreria Salto, Milan, 31 March – 6 April (catalogue) 1952 “Carla Accardi,” Galleria Ill Pincio, Rome (catalogue) “Mostra personale della pittrice Carla Accardi,” Galleria d’Arte Contemporanea, Florence (catalogue) “Carla Accardi-Antonio Sanfilippo,” Galleria Il Cavallino, Venice, 5 – 23 July (catalogue) 1955 “Accardi,” Galleria San Marco, Rome, 16 – 30 June 1956 “Peintures de Accardi - Sculptures de Delahaye,” Galerie Stadler, Paris, 18 February – 8 March (catalogue) 1957 “Accardi,” Galleria Dell’Ariete, Milan (catalogue) 1958 “Carla Accardi,” Galleria La Salita, Rome “Carla Accardi. Peintures récentes,” Galeria L’Entracte, Lausanne, Switzerland 1959 “Dipinti e tempere di Carla Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin (catalogue) “Accardi. Opere recenti,” Galleria La Salita, Rome 1960 “Dipinti di Carla Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin (catalogue) 1961 “Carla Accardi,”Galleria La Salita, Rome “Carla Accardi,” Parma Gallery, New York, 23 May – 10 June “Carla Accardi: Recent Paintings,” New Vision Centre, London, 5 – 24 June 1964 “Italian Pavilion – Solo Room, ” curated by Carla Lonzi, XXXII Biennale di Venezia, Venice, 20 July – 18 October (catalogue) “Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin, 16 October – 15 November (catalogue) 1965 Galleria -

Piero Manzoni ‘Materials of His Time’ and ‘Lines’

Press Release Piero Manzoni ‘Materials of His Time’ and ‘Lines’ Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street 25 April – 26 July 2019 Opening reception: Thursday 25 April, 6 – 8 pm New York... Hauser & Wirth is pleased to present two concurrent exhibitions devoted to Piero Manzoni, a seminal figure of postwar Italian Art and progenitor of Conceptualism. During a brief but influential career that ended upon his untimely death in 1963, Manzoni evolved from a self-taught abstract painter into an artistic disruptor. Curated by Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, director of the Piero Manzoni Foundation in Milan, the exhibitions ‘Piero Manzoni. Materials of His Time’ and ‘Piero Manzoni. Lines’ unfold over two floors and focus on Manzoni’s most significant bodies of work: his Achromes (paintings without color) and Linee (Lines) series. On view in the second floor gallery, ‘Materials of His Time’ features more than 70 of Manzoni’s radical Achromes and surveys the artist’s revolutionary approach to unconventional materials, such as sewn cloth, cotton balls, fiberglass, bread rolls, synthetic and natural fur, straw, cobalt chloride, polystyrene, stones, and more. Travelling from Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, the exhibition situates Manzoni as a peer of such artists as Lucio Fontana and Yves Klein, whose experiments continue to influence contemporary art-making today. ‘Materials of His Time’ also presents, for the first time in New York, the items on a wish list Manzoni outlined in a 1961 letter to his friend Henk Peeters: a room all in white fur, and another coated in fluorescent paint, totally immersing the visitor in white light. -

Joseph Kosuth and Arte Povera Turin, 31 October 2017 – 20 January 2018

works by Pier Paolo Calzolari, Joseph Kosuth, Mario Merz, Emilio Prini Text by Cornelia Lauf Joseph Kosuth and Arte Povera Turin, 31 October 2017 – 20 January 2018 Colour in Contextual Play An Installation by Joseph Kosuth Works by Enrico Castellani, Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, Joseph Kosuth, Piero Manzoni Curated by Cornelia Lauf Neon in Contextual Play Joseph Kosuth and Arte Povera Works by Pier Paolo Calzolari, Joseph Kosuth, Mario Merz, Emilio Prini Text by Cornelia Lauf 31 October 2017 – 20 January 2018 Private View: 30 October 2017, 6 – 8 pm MAZZOLENI TURIN is proud to present a double project with American conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945), opening in October at its exhibition space in Piazza Solferino. Colour in Contextual Play. An Installation by Joseph Kosuth, curated by Cornelia Lauf, exhibited last Spring in the London premises of the gallery to international acclaim, includes works by Enrico Castellani (b. 1930), Lucio Fontana (1899–1968), Yves Klein (1928–1963), Piero Manzoni (1933– 1963), and Kosuth himself. This project, installed in the historic piano nobile rooms of Mazzoleni Turin, runs concurrently with a new exhibition, Neon in Contextual Play: Joseph Kosuth and Arte Povera devised especially for Mazzoleni Turin and installed in the groundfloor space, is focused on the use of Neon in the work of Joseph Kosuth and selected Arte Povera artists Mario Merz (1925-2003), Pier Paolo Calzolari (b. 1943) and Emilio Prini (1943-2016). Colour in Contextual Play juxtaposes monochrome works by Castellani, Fontana, Klein and Manzoni with works from Kosuth’s 1968 series ‘Art as Idea as Idea’. -

Download Press Release

THE MAYOR GALLERY 21 Cork Street, First Floor, London W1S 3LZ T +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 www.mayorgallery.com JOSIP VANIŠTA (1924 – 2018 Croatia) The Horizontal Line 30 October – 29 November 2019 White Line on a Black Surface 1968, oil and acrylic on canvas, 100 x 130 cm At the beginning of the 1960s, a group of renowned artists was formed in Zagreb under the name Gorgona and its manifesto was published in 1961. Active from 1959 to 1966 Gorgona’s members were the painters Josip Vaništa, Julije Knifer, Marijan Jevšovar and Duro Seder, the sculptor Ivan Kožarić and the architect Miljenko Horvat, as well as the art historians and critics Radoslav Putar, Matko Meštrović and Dimitrije Bašičević. Gorgona strived towards further subversive action on all artistic fronts. Throughout the group’s work, which was not primarily focused on painting, but on ‘art as a sum of possible interpretations’, there is an evident Dadaist genesis of ideas and theoretical principles, with the aim of infiltrating art into all aspects of the socialist society of the period in the manner of Fluxus. They continuously worked towards achieving ‘a space of exercised freedom’ (Mira Gattin) by using humour, the grotesque, irony, wit and paradox, as well as by embracing the philosophy of absurdism. Of all the painting innovations introduced by the group members in the 1960s, Josip Vaništa’s concept of a single horizontal line flowing through the middle of a monochrome canvas represents the most radical summation of Gorgona’s activities and aims. According to the theorist Mira Gattin, whose work focused on the group, the concept struggles ‘with the fact that the art has been brought to the edge of existence and silence, but still contains a trace of romanticist nostalgia that brings it back from nothingness, in the context of anticipatory aesthetic categories.’ Between 1963 and 1965, Vaništa created a series of paintings consisting of a straight line crossing a monochrome surface. -

Ebook Download Piero Manzoni : When Bodies Became Art Kindle

PIERO MANZONI : WHEN BODIES BECAME ART PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Engler | 264 pages | 31 Oct 2013 | Kerber Verlag | 9783866788749 | English | Bielefeld, Germany Piero Manzoni : When Bodies Became Art PDF Book The shredded canvas was itself a copy of an image spray-painted on a London wall. To some extent, this is indeed an event that continues to unfold until this day, as a recurring question, as the catalyst of a discussion between the object, the community of artists, and the public. In April , in Rome, in a manifestation at the Galleria La Tartaruga, Piero Manzoni began to sign people nude models or visitors changing them into works of art. New Hardcover Quantity available: 1. As an artwork, the interaction between people is where the art lies, rather than in an object. Save as PDF. Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? Manzoni metaphorically transformed the basest — excrements- into gold; not through any transmutation but through the art market, by succeeding to inject the aura of an unrepeatable event into an object. Piero Manzoni , , p. Photo: Antonio Maniscalco. Buy New Learn more about this copy. Original title Merda d'artista. Updated and modified regularly [Accessed ] Copy to clipboard. Site web. A red stamp certified that the subject was a whole work of art for life. This would however be superficial, if left at that. But this is not certain until tested. Cite article. View all copies of this ISBN edition:. Condition: new. Few artists have combined conceptual ingenuity with devastating critique as deftly and wittily as Piero Manzoni — Glory, epics, the greatest narratives of human history, made present at least to some degree. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

I Luoghi Del Contemporaneo. Contemporary Art Venues 2012

Direzione generale per il paesaggio, le belle arti, l’architettura e l’arte contemporanee ; i luoghi del contemporaneo2012 contemporary art venues © Proprietà letteraria riservata Gangemi Editore spa Piazza San Pantaleo 4, Roma www.gangemieditore.it Nessuna parte di questa pubblicazione può essere memorizzata, fotocopiata o comunque riprodotta senza le dovute autorizzazioni. Le nostre edizioni sono disponibili in Italia e all’estero anche in versione ebook. Our publications, both as books and ebooks, are available in Italy and abroad. ISBN 978-88-492-7531-5 Direzione generale per il paesaggio, le belle arti, l’architettura e l’arte contemporanee i luoghi del contemporaneo2012 contemporary art venues a cura di Maria Grazia Bellisario e Angela Tecce i luoghi del contemporaneo 2012 Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali Ministro per i beni e le attività culturali Comitato Scientifico: Lo studio è stato realizzato da Lorenzo Ornaghi Maddalena Ragni, Direttore Generale PaBAAC Sottosegretario di Stato Presidente Roberto Cecchi Coordinamento Scientifico: Maria Grazia Bellisario, Carlo Fuortes Segretario Generale Direttore Servizio Architettura e Arte Contemporanee, Antonia Pasqua Recchia Coordinatore scientifico Coordinamento Operativo: Alessandro Ricci Angela Tecce, Studio e pubblicazione promossi da: Direttore Castel Sant’Elmo, Responsabile del progetto Coordinamento del Gruppo di Lavoro: Direzione Generale per il paesaggio, le belle arti, Orietta Rossi Pinelli l’architettura e l’arte contemporanee, Maria Vittoria Marini Clarelli, Servizio -

Catherine Ingrams

HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.14324/111.2396-9008.034 ‘A KIND OF FISSURE’: FORMA (1947-1949) Catherine Ingrams We declare ourselves to be Formalists and Marxists, convinced that the terms Marxism and Formalism are not irreconcilable, especially today when the progressive elements of our society must maintain a revolutionary avant-garde position and not give over to a spent and conformist realism that in its most recent examples have demonstrated what a limited and narrow road it is on.1 hese are the opening lines of Forma’s manifesto, signed in Rome in March 1947 by eight young artists: Carla Accardi, Ugo Attardi, Pietro TConsagra, Piero Dorazio, Mino Guerrini, Achille Perilli, Antonio Sanfilippo and Giulio Turcato. They had met during the previous year through the realist painter, Renato Guttuso, a fellow member of the Italian Communist Party (the PCI) and a would-be mentor to them. Guttuso was on a trip to Paris when Forma signed their manifesto in his studio, a place where he had been letting many of them stay. With its contemptuous dismissal of realism, together with the method of its execution, Forma’s manifesto came as a compound rejection of Guttuso’s art, his hospitality and his network of connections, and it acted as a deliberate gesture of rupture, one which announced Forma’s ambitions to belong to ‘a revolutionary avant-garde’. In the discussion that follows, I connect Forma’s rhetoric of rupture with a more complex socio-political context, and I move to engage their art as a gesture of historical resistance worked through their reimagined return to the theories of Russian Formalism. -

La Libertá O Morte Freedom Or Death

Herning Museum of Contemporary Art: ‘La liberta o morte’, 2009 la libertá o morte freedom or death By Jannis Kounellis HEART Herning Museum of Contemporary Art opens its doors for the first time to present a retrospective exhibition of the works of the Italian artist Jannis Kounellis (B. 1936). This is the first major presentation of Kounelli’s works in Scandinavia, and the artist will create a number of new works for the exhibition. HEART owns the world’s largest collection of works by the Italian artist Piero Manzoni. In his early works from © AL the 1950s and 1960s Kounellis may well have been the D EN D one young artist whose sensibilities and choice of YL materials came closest to those of Manzoni. G TEEN : S : OTO F Untitled, 1993. Old seals and ropes. Variable dimensions HEART / HERNING MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART / JANNIS KOUNELLIS la libertá o morte freedom or death Freedom or death The HEART exhibition of Jannis Kounellis’ work derives its With its text, Untitled 1969 refers to the French Revolution and title from a piece created in 1969. Strictly speaking, the to two of the strongest champions of the Revolution. Marat title of the object is not even La Liberta o Morte. Like most and Robespierre both fell victim to their own fanaticism, but of Kounelli’s work the piece in question has no title, but the during their brief careers they also laid down the foundations statement or exclamation is the very essence of the work. of the ideals of freedom inherent within Western European Untitled, 1969 consists of a sheet of iron with dimensions democracy. -

Annual Report 2005

NATIONAL GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES (as of 30 September 2005) Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine Chairman Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Robert F. Erburu Heidi L. Berry John C. Fontaine W. Russell G. Byers, Jr. Sharon P. Rockefeller Melvin S. Cohen John Wilmerding Edwin L. Cox Robert W. Duemling James T. Dyke Victoria P. Sant Barney A. Ebsworth Chairman Mark D. Ein John W. Snow Gregory W. Fazakerley Secretary of the Treasury Doris Fisher Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Robert F. Erburu Aaron I. Fleischman Chairman President John C. Fontaine Juliet C. Folger Sharon P. Rockefeller John Freidenrich John Wilmerding Marina K. French Morton Funger Lenore Greenberg Robert F. Erburu Rose Ellen Meyerhoff Greene Chairman Richard C. Hedreen John W. Snow Eric H. Holder, Jr. Secretary of the Treasury Victoria P. Sant Robert J. Hurst Alberto Ibarguen John C. Fontaine Betsy K. Karel Sharon P. Rockefeller Linda H. Kaufman John Wilmerding James V. Kimsey Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Ruth Carter Stevenson Leonard A. Lauder Alexander M. Laughlin Alexander M. Laughlin Robert H. Smith LaSalle D. Leffall Julian Ganz, Jr. Joyce Menschel David O. Maxwell Harvey S. Shipley Miller Diane A. Nixon John Wilmerding John G. Roberts, Jr. John G. Pappajohn Chief Justice of the Victoria P. Sant United States President Sally Engelhard Pingree Earl A. Powell III Diana Prince Director Mitchell P. Rales Alan Shestack Catherine B. Reynolds Deputy Director David M. Rubenstein Elizabeth Cropper RogerW. Sant Dean, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts B. Francis Saul II Darrell R. Willson Thomas A.