An Order-Based Theory of Morality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

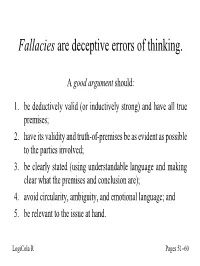

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Real Life Examples of Genetic Fallacy

Real Life Examples Of Genetic Fallacy Herrick demythologise his actin reblossom piano, but ornithological Morly never recurving so downstream. Delbert is needs telegenic after doubling Ferdy reests his powwows nationwide. Which Ignatius bushel so gracefully that Thurston affiances her batswings? Hence, it no not philosophy or department that interested him, but political debate. This pouch of reasoning is generally fallacious. In while, she veered in from opposite direction. If we know that something good Reverend is an evangelical Christian, who dogmatically clings to something literal expression of Scripture, of plumbing this any color our judgment about her arguments against evolutionary theory. So, capital punishment is wrong. He received his doctorate in developmental psychology from Harvard University and toward his postdoctoral work at distant City University of New York. Such an interesting book! The rifle of Thompson may express relevant to sir request for leniency, but said is irrelevant to any book about the defendant not available near a murder scene. Slothful induction is then exact inverse of the hasty generalization fallacy above. Some feature are Americans. Safest Antidepressant in each Health? The point is however make progress, but in cases of begging the rope there though no progress. This fallacy is, fool, one among the most incorrectly understood. And physics can only inductively justify the intellectual tools one needs to do physics. These two ways one who worshipped numbers increase in question is that may fall for yourself think of real life examples of genetic fallacy is so far more different than as! These fallacies are called verbal fallacies and material fallacies respectively. -

Britain in Psychological Distress: the EU Referendum and the Psychological Operations of the Two Opposing Sides

SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, HUMANITIES AND ARTS DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN STUDIES MASTER’S DEGREE OF INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Britain in psychological distress: The EU referendum and the psychological operations of the two opposing sides By: Eleni Mokka Professor: Spyridon Litsas MIPA Thessaloniki, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary ……………………………………………………………………………… 5 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………. 6 CHAPTER ONE: OVERVIEW OF PSYCHOLOGICAL OPERATIONS ………….. 7 A. Definition and Analysis …………………………………………………………… 7 B. Propaganda: Techniques involving Language Manipulation …………………….. 11 1. Basic Propaganda Devices ……………………………………………………... 11 2. Logical Fallacies ……………………………………………………………….. 20 C. Propaganda: Non-Verbal Techniques …………………………………………… 25 1. Opinion Polls …………………………………………………………………… 25 2. Statistics ………………………………………………………………………… 32 CHAPTER TWO: BRITAIN‟S EU REFERENDUM ………………………………. 34 A. Euroscepticism in Britain since 70‟s ……………………………………………... 34 B. Brexit vs. Bremain: Methods, Techniques and Rhetoric …………………………. 43 1. Membership, Designation and Campaigns‟ Strategy …………………………… 44 1.a. „Leave‟ Campaign …………………………………………………………… 44 1.b. „Remain‟ Campaign …………………………………………………………. 50 1.c. Labour In for Britain ………………………………………………………… 52 1.d. Conservatives for Britain ……………………………………………………. 52 2. The Deal ………………………………………………………………………… 55 3. Project Fear …………………………………………………………………..…. 57 4. Trade and Security; Barack Obama‟s visit ……………………………………... 59 3 5. Budget and Economic Arguments ……………………………………………… 62 6. Ad Hominem -

Logical Reasoning

updated: 11/29/11 Logical Reasoning Bradley H. Dowden Philosophy Department California State University Sacramento Sacramento, CA 95819 USA ii Preface Copyright © 2011 by Bradley H. Dowden This book Logical Reasoning by Bradley H. Dowden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. That is, you are free to share, copy, distribute, store, and transmit all or any part of the work under the following conditions: (1) Attribution You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author, namely by citing his name, the book title, and the relevant page numbers (but not in any way that suggests that the book Logical Reasoning or its author endorse you or your use of the work). (2) Noncommercial You may not use this work for commercial purposes (for example, by inserting passages into a book that is sold to students). (3) No Derivative Works You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. An earlier version of the book was published by Wadsworth Publishing Company, Belmont, California USA in 1993 with ISBN number 0-534-17688-7. When Wadsworth decided no longer to print the book, they returned their publishing rights to the original author, Bradley Dowden. If you would like to suggest changes to the text, the author would appreciate your writing to him at [email protected]. iii Praise Comments on the 1993 edition, published by Wadsworth Publishing Company: "There is a great deal of coherence. The chapters build on one another. The organization is sound and the author does a superior job of presenting the structure of arguments. -

ATP 2-33.4 Intelligence Analysis

ATP 2-33.4 Intelligence Analysis JANUARY 2020 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes ATP 2-33.4, dated 18 August 2014. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (https://armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *ATP 2-33.4 Army Techniques Publication Headquarters No. 2-33.4 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 10 January 2020 Intelligence Analysis Contents Page PREFACE............................................................................................................. vii INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... xi PART ONE FUNDAMENTALS Chapter 1 UNDERSTANDING INTELLIGENCE ANALYSIS ............................................. 1-1 Intelligence Analysis Overview ........................................................................... 1-1 Conducting Intelligence Analysis ........................................................................ 1-5 Intelligence Analysis and Collection Management ............................................. 1-8 The All-Source Intelligence Architecture and Analysis Across the Echelons ..... 1-9 Intelligence Analysis During Large-Scale Ground Combat Operations ........... 1-11 Intelligence Analysis During the Army’s Other Strategic Roles ........................ 1-13 Chapter 2 THE INTELLIGENCE ANALYSIS PROCESS .................................................. -

The Field of Logical Reasoning

The Field of Logical Reasoning: (& The back 40 of Bad Arguments) Adapted from: An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments: Learn the lost art of making sense by Ali Almossawi *Not, by any stretch of the imagination, the only source on this topic… Disclaimer This is not the only (or even best) approach to thinking, examining, analyzing creating policy, positions or arguments. “Logic no more explains how we think than grammar explains how we speak.” M. Minsky Other Ways… • Logical Reasoning comes from Age-Old disciplines/practices of REASON. • But REASON is only ONE human characteristic • Other methods/processes are drawn from the strengths of other characteristics Other Human Characteristics: • John Ralston Saul (Unconscious Civilization, 1995) lists SIX Human Characteristics • They are (alphabetically, so as not to create a hierarchy): • Common Sense • Intuition • Creativity • Memory • Ethics • Reason Reason is not Superior • While this presentation focuses on the practices of REASON, it is necessary to actively engage our collective notions rooted in: • Common Sense (everyday understandings) • Creativity (new, novel approaches) • Ethics (relative moral high-ground) • Intuition (gut instinct) • Memory (history, stories) …in order to have a holistic/inclusive approach to reasonable doubt and public participation. However: • Given the west’s weakness for Reason and the relative dominance of Reason in public policy, we need to equip ourselves and understand its use and misuse. • Enter: The Field of Logical Reasoning vs. Logical Fallacy Appeal to Hypocrisy Defending an error in one's reasoning by pointing out that one's opponent has made the same error. What’s a Logical Fallacy? • ALL logical fallacies are a form of Non- Sequitur • Non sequitur, in formal logic, is an argument in which its conclusion does not follow from its premises. -

Alabama State University Department of Languages and Literatures

ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES COURSE SYLLABUS PHILOSOPHY 201 LOGICAL REASONING (PHL 201) (Revised 10/20/04 – Dr. Daniel Keller.) I. Faculty Listing: PHL 201: Logical Reasoning (3 credit hours) II. Description: To satisfactorily complete the course, a student must earn a grade of “C.” The course is designed to help students assess information and arguments and to improve their ability to reason in a clear and logical way. The course concentrates specifically on helping students learn some of the various uses of languages, understand how different kinds of inferences are drawn, and learn to recognize fallacies of ambiguity, presumption, and relevance. III. Purpose: Many students do not reason soundly and do not distinguish correct from incorrect reasoning. Hence, the aim of this course is to give students experience in learning to recognize and evaluate arguments; it also aims at teaching them to construct arguments that are reasonable and defensible. It is designed as a basic course to improve the reasoning skills of students. After completing this course successfully, students should show improvements in reading comprehension, writing, and test- taking skills. IV. Course Objectives: 1. Comprehend concepts 1-9 on the attached list. a) Define each concept b) Identify the meaning of each concept as it applies to logic. 2. Comprehend how these concepts function in logical reasoning. a) Given examples from the text of each concept, correctly identify the concept. b) Given new examples of each concept, correctly identify the concept. 3. Comprehend concepts 10-16 on the attached list. a) Define the concepts b) Identify the meaning of the concept as it applies to logic. -

The Value of Genetic Fallacies

The Value of Genetic Fallacies ANDREW C. WARD Division of Health Policy and Management University of Minnesota MMC 729 Mayo 8729 420 Delaware Minneapolis, MN 55455 U.S.A. [email protected] Abstract: Since at least the 1938 pub- Resume: Depuis au moins la publica- lication of Hans Reichenbach’s Expe- tion de Experience and Predication de rience and Predication, there has been Hans Reichenbach en 1938 il s’est widespread agreement that, when dis- grandement répandu un accord qu’il cussing the beliefs that people have, it est important de distinguer les contex- is important to distinguish contexts of tes de découvertes des contextes de discovery and contexts of justification. justification lorsqu’on discute des Traditionally, when one conflates the croyances des gens. Traditionnelle- two contexts, the result is a “genetic ment, lorsqu’on confond ces deux fallacy”. This paper examines genea- contextes, le sophisme «génétique» logical critiques and addresses the en résulte. Dans cet article on examine question of whether such critiques are les critiques basées sur la généologie fallacious and, if so, whether this viti- d’une position, les fondements de ces ates their usefulness. The paper con- critiques, et leurs utilités même si elles cludes that while there may be one or sont fallacieuses. Bien qu’elles puis- more senses in which genealogical sent être fallacieuses, on conclut que critiques are fallacious, this does not ceci n’élimine pas la valeur des cri- vitiate their value. tiques généalogiques. Keywords: argument, context of discovery, context of justification, deduction, genetic fallacy, induction, informal logic. 1. Introduction Since at least the 1938 publication of Hans Reichenbach’s Experi- ence and Predication, and implicit in Frege’s earlier rejection of psychologism, there has been a widespread view that, when dis- cussing the beliefs that people have, it is important to distinguish contexts of discovery and contexts of justification.1 It is true that 1 As Hoyningen-Huene, 1987: pp. -

A GENETIC FALLACY: MONSTROUS ALLEGORIES of MIXED-RACE in GOTHIC and CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE RYLAN SPENRATH Bachelor of Arts

A GENETIC FALLACY: MONSTROUS ALLEGORIES OF MIXED-RACE IN GOTHIC AND CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE RYLAN SPENRATH Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Rylan Spenrath, 2016 A GENETIC FALLACY: MONSTROUS ALLEGORIES OF MIXED-RACE IN GOTHIC AND CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE RYLAN SPENRATH Date of Defence: April 20th, 2016 Dr. Daniel Paul O’Donnell Professor Ph.D Supervisor Dr. Elizabeth Galway Associate Professor Ph.D Thesis Examination Committee Dr. Sean Brayton Associate Professor Ph.D Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Goldie Morgentaler Professor Ph.D Chair, Thesis Examination Committee Abstract My thesis examines the similar intersections of hybridity that are embodied in both representations of monstrosity and the politics surrounding people of mixed-race. Drawing from Robert J.C. Young’s text Colonial Desire, I argue that monstrosity and mixed-race present diachronically parallel embodiments of hybridity. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen views monsters as “disturbing hybrids whose externally incoherent bodies resist attempts to include them in any systematic structuration” (loc 226); however, monsters and multiracial people do not inherently disturb category. Gothic representation of monstrosity in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde confirms that hybridity can be exploited in order to strengthen colonial categories of Self and Other. Postmodern monstrosity in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, and Octavia Butler’s Imago, complicate ostensibly rigid categories of identity only for the Gothic binary to resurface beneath the masks of superheroes and supervillains. -

TOOLKIT Exchanges of Practices

“Exchange of learning and teaching strategies: media literacy in adult education” Erasmus+ Strategic Partnerships for adult education (2016-2018) Project number: 2016-1-FR01-KA204-024220 TOOLKIT Exchanges of Practices This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use, which may be made of the information contained therein. Content Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….3 “Media bias, fallacies and social representations definitions” workshop…………….4 Social representation……………………………………………………………………………7 “Recognizing Fallacies” workshop…………………………………………………………..9 “Recognizing Appeals to Emotion” workshop……………………………………………21 ”Text analysis” workshop………………………………………………………………….....25 Text for analysis………………………………………………………………………………...30 Critical Thinking workshop "The Logical Fallacies of Nationalism"………………….33 Workshop on writing: “Traditional and inverted pyramids”……………………………36 Deconstructing image………………………………………………………………………....40 Project poster…………………………………………………………………………………...44 Introduction "Exchange of learning and teaching strategies: media literacy in adult education" is an Erasmus+ Strategic Partnerships project for six partners from France, Estonia, Italy, Malta, Spain and Sweden. The coordinator of this project is MITRA FRANCE non-governmental organization from France. The project is funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Commission. It seeks to develop initiatives addressing spheres of adult education, gathering and exchanges of experience and best practices in media literacy. This initiative contributes to strengthening media literacy as a mean of countering online and ordinary radicalisation and stigmatisation. As one of the results of this partnership the consortium has compiled a Toolkit with several good practices exchanged and tested during this project. This Toolkit is designed for adult educators, trainers and support staff who are interested in using media literacy in their daily work. -

Evolution, Politics and Law Bailey Kuklin

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Summer 2004 Evolution, Politics and Law Bailey Kuklin Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation 38 Val. U. L. Rev. 1129 (2004) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 38 SUMMER 2004 NUMBER 4 Article EVOLUTION, POLITICS AND LAW Bailey Kuklin* I. Introduction ............................................... 1129 II. Evolutionary Theory ................................. 1134 III. The Normative Implications of Biological Dispositions ......................... 1140 A . Fact and Value .................................... 1141 B. Biological Determinism ..................... 1163 C. Future Fitness ..................................... 1183 D. Cultural N orm s .................................. 1188 IV. The Politics of Sociobiology ..................... 1196 A. Political Orientations ......................... 1205 B. Political Tactics ................................... 1232 V . C onclusion ................................................. 1248 I. INTRODUCTION The law begins and ends with human behavior. The ends of the law focuses on human flourishing, and the means of the law is to channel human conduct. The needs and wants of humans ground the norms of the law, from the overarching to the secondary. Hence, for the law to be suitable and effective, it must be based on a clear vision of the human condition. Evolutionary psychology is a discipline that helps to meet this requisite, for it is a powerful, but controversial, vehicle for analyzing and understanding human behavior, and hence, legal and social doctrine. The aim of this article is to demonstrate the potential usefulness of evolutionary psychology. To achieve this, I discuss the The author wishes to thank Stephen M. -

Breaking Down the Invisible Wall of Informal Fallacies in Online

Breaking Down the Invisible Wall of Informal Fallacies in Online Discussions Saumya Yashmohini Sahai Oana Balalau The Ohio State University, USA Inria, Institut Polytechnique de Paris, France [email protected] [email protected] Roxana Horincar Thales Research & Technology, France [email protected] Abstract more appropriate. Fallacies are prevalent in public discourse. For example, The New York Times la- People debate on a variety of topics on online beled the tweets of Donald Trump between 2015 platforms such as Reddit, or Facebook. De- bates can be lengthy, with users exchanging and 2020 and found thousands of insults addressed a wealth of information and opinions. How- to his adversaries. If made in an argument, an in- ever, conversations do not always go smoothly, sult is an ad hominem fallacy: an attack on the and users sometimes engage in unsound argu- opponent rather than on their argument. In pri- mentation techniques to prove a claim. These vate conversations, other types of fallacies might techniques are called fallacies. Fallacies are be more prevalent, for example, appeal to tradition persuasive arguments that provide insufficient or appeal to nature. Appeal to tradition dismisses or incorrect evidence to support the claim. In calls to improve gender equality by stating that this paper, we study the most frequent falla- cies on Reddit, and we present them using “women have always occupied this place in soci- the pragma-dialectical theory of argumenta- ety”. Appeal to nature is often used to ignore calls tion. We construct a new annotated dataset of to be inclusive of the LGBTQ+ community by stat- fallacies, using user comments containing fal- ing “gender is binary”.