Evolution, Politics and Law Bailey Kuklin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociobiology in Turmoil Again

GENERAL ARTICLES Sociobiology in turmoil again Raghavendra Gadagkar Altruism is defined as any behaviour that lowers the Darwinian fitness of the actor while increasing that of the recipient. Such altruism (especially in the form of lifetime sterility exhibited by sterile workers in eusocial insects such as ants, bees, wasps and termites) has long been considered a major difficulty for the theory of natural selection. In the 1960s W. D. Hamilton potentially solved this problem by defining a new measure of fitness that he called inclusive fitness, which also included the effect of an individual’s action on the fitness of genetic relatives. This has come to be known as inclusive fitness theory, Hamilton’s rule or kin selection. E. O. Wilson almost single-handedly popularized this new approach in the 1970s and thus helped create a large body of new empirical research and a large community of behavioural ecologists and kin selectionists. Adding thrill and drama to our otherwise sombre lives, Wilson is now leading a frontal attack on Hamilton’s approach, claiming that the inclusive fitness theory is not as mathematically general as the standard natural selection theory, has led to no additional biological insights and should therefore be aban- doned. The world cannot but sit up and take notice. Keywords: Altruism, eusociality, Hamilton’s rule, inclusive fitness theory, kin selection, sociobiology. THE science of sociobiology is in turmoil again and this Altruism and eusociality time on theoretical grounds. And yes, E. O. Wilson (of Harvard University) is at the epicentre of it; but, believe Among the various kinds of social interactions seen it or not, this time around he is leading the attack and his commonly in group-living species, the most paradoxical followers (erstwhile?) are at the receiving end. -

Interpreting the History of Evolutionary Biology Through a Kuhnian Prism: Sense Or Nonsense?

Interpreting the History of Evolutionary Biology through a Kuhnian Prism: Sense or Nonsense? Koen B. Tanghe Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Lieven Pauwels Department of Criminology, Criminal Law and Social Law, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Alexis De Tiège Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Johan Braeckman Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Traditionally, Thomas S. Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) is largely identified with his analysis of the structure of scientific revo- lutions. Here, we contribute to a minority tradition in the Kuhn literature by interpreting the history of evolutionary biology through the prism of the entire historical developmental model of sciences that he elaborates in The Structure. This research not only reveals a certain match between this model and the history of evolutionary biology but, more importantly, also sheds new light on several episodes in that history, and particularly on the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), the construction of the modern evolutionary synthesis, the chronic discontent with it, and the latest expression of that discon- tent, called the extended evolutionary synthesis. Lastly, we also explain why this kind of analysis hasn’t been done before. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive review, as well as the editor Alex Levine. Perspectives on Science 2021, vol. 29, no. 1 © 2021 by The Massachusetts Institute of Technology https://doi.org/10.1162/posc_a_00359 1 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/posc_a_00359 by guest on 30 September 2021 2 Evolutionary Biology through a Kuhnian Prism 1. -

Natural Necessity Natural Selection

NATURAL SELECTION NATURAL NECESSITY See Laws of Nature NATURAL SELECTION In modern evolutionary biology, a set of objects is Adaptationism said to experience a selection process precisely when At the close of his introduction to those objects vary in/itness (see Fitness). For exam On the Origin oj' ple, if zebras that run fast are fitter than zehras that Species, Darwin [1859] 1964, 6 says that natural selection is "the main but not the exclusive" cause run slow (perhaps because faster zebras are better ofevolution. In reaction to misinterpretations ofhis able to avoid lion predation), a selection process is theory, Darwin felt compelled to reemphasize, in the set in motion. If the trait that exhibits variation hook's last edition, that there was more to evolution in fit~ess is heritable-meaning, in our example, that faster parents tend to have faster offspring than natural selection. It remains a matter of con troversy in evolutionary biology how important and slower parents tend to have slower offspring then the selection process is apt to chancre trait natural selection has been in the history of life. frequencies in the population, leading fitte';. traits This is the poinl of biological substance that pres to increase in frequency and less fit traits to decline ently divides adaptationists and anti-adaptationists. The debate over adaptationism also has a separate (Lewontin 1970). This change is the one that selec tion is "apt" to engender, rather than the one that methodological dimension, with critics insisting that adaptive hypotheses be tested more rigorously must occur, because evolutionary theory describes <Gould and Lewontin 1979; Sober 1993). -

Evolution and Ethics 2

It is still disputed, however, why moral behavior extends beyond a close circle of kin and reciprocal relationships: e.g., most people think stealing from anyone is wrong, not just stealing from family and friends. For moral behavior to evolve as we understand it today, there likely had to be selective pressures that pushed people to disregard their own 1000wordphilosophy.com/2018/10/11/evolution- interests in favor of their group’s interest.[3] Exactly and-ethics/ how morality extended beyond this close circle is debated, with many theories under consideration.[4] Evolution and Ethics 2. What Should We Do? Author: Michael Klenk Suppose our ability to understand and apply moral Category: Ethics, Philosophy of Science rules, as typically understood, can be explained by Word Count: 999 natural selection. Does evolution explain which rules We often follow what are considered basic moral we should follow?[5] rules: don’t steal, don’t lie, help others when we can. Some answer, “yes!” “Greed captures the essence of But why do we follow these rules, or any rules the evolutionary spirit,” says the fictional character understood as “moral rules”? Does evolution explain Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street: “Greed why? If so, does evolution have implications for … is good. Greed is right.”[6] which rules we should follow, and whether we genuinely know this? Gekko’s claims about what is good and right and what we ought to be comes from what he thinks we This essay explores the relations between evolution naturally are: we are greedy, so we ought to be and morality, including evolution’s potential greedy. -

Revisiting the Eclipse of Darwinism

Journal of the History of Biology (2005) 38: 19–32 Ó Springer 2005 DOI: 10.1007/s10739-004-6507-0 Revisiting the Eclipse of Darwinism PETER J. BOWLER School of Anthropological Studies Queen’s University Belfast BT7 1NN Northern Ireland UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The article sums up a number of points made by the author concerning the response to Darwinism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and repeats the claim that a proper understanding of the theory’s impact must take account of the extent to which what are now regarded as the key aspects of Darwin’s thinking were evaded by his immediate followers. Potential challenges to this position are described and responded to. Keywords: anti-Darwinism, Darwinism, eclipse of Darwinism Having written books with titles such as The Eclipse of Darwinism and The Non-Darwinian Revolution, I could hardly resist the offer to produce an overview of my current thinking on the status of the Darwinian revolution. My ideas have certainly developed over the years, but in a reasonably consistent manner. Each book has, in a sense, created the question that had to be answered in the next. The initial purpose was only to document the temporary explosion of interest in non-Darwinian ideas of evolutionism in the late nineteenth century. But once it became apparent that even some ostensible supporters of Darwinism adopted positions that would never be included under that name today, it be- came necessary to rethink the relationship between early and modern Darwinism, and to reassess why Darwin’s work was taken so seriously when it was first published. -

The Strange Survival and Apparent Resurgence of Sociobiology

This is a repository copy of The strange survival and apparent resurgence of sociobiology. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118157/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Dennis, A. orcid.org/0000-0003-4625-1123 (2018) The strange survival and apparent resurgence of sociobiology. History of the Human Sciences, 31 (1). pp. 19-35. ISSN 0952- 6951 https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695117735966 Dennis A. The strange survival and apparent resurgence of sociobiology. History of the Human Sciences. 2018;31(1):19-35. Copyright © 2017 The Author(s). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695117735966. Article available under the terms of the CC- BY-NC-ND licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The strange survival and apparent resurgence of sociobiology Abstract A recent dispute between Richard Dawkins and Edward O. Wilson concerning fundamental concepts in sociobiology is examined. -

Evolution, Politics and Law

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 38 Number 4 Summer 2004 pp.1129-1248 Summer 2004 Evolution, Politics and Law Bailey Kuklin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bailey Kuklin, Evolution, Politics and Law, 38 Val. U. L. Rev. 1129 (2004). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol38/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Kuklin: Evolution, Politics and Law VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 38 SUMMER 2004 NUMBER 4 Article EVOLUTION, POLITICS AND LAW Bailey Kuklin* I. Introduction ............................................... 1129 II. Evolutionary Theory ................................. 1134 III. The Normative Implications of Biological Dispositions ......................... 1140 A . Fact and Value .................................... 1141 B. Biological Determinism ..................... 1163 C. Future Fitness ..................................... 1183 D. Cultural N orm s .................................. 1188 IV. The Politics of Sociobiology ..................... 1196 A. Political Orientations ......................... 1205 B. Political Tactics ................................... 1232 V . C onclusion ................................................. 1248 I. INTRODUCTION -

Sociobiology and the Origins of Ethics

SOCIOBIOLOGY AND THE ORIGINS OF ETHICS JULIO MUÑOZ-RUBIO ABSTRACT. According to sociobiology, ethics is an offspring of natural selection and totally explicable through biology. According to this discipline, any indi- vidual has reproduction as its supreme life objective, and thus ethical principles are directly originated from such objective. This criterion subordinates choice to “natural” duties and eradicates the power of human free will to generate values. Sociobiology falls into the natural fallacy as it assumes that a moral “duty” derived from a particular behavior is justified by the same existence of such behavior. This paper sustains that humans are qualitative different from the rest of animals since they exist in spheres afar from strict biological ones; sociobiology subjugates human freedom to the necessity realm and build up an ideological discourse. KEY WORDS. Ethics, evolutionary theory, ideology, naturalist fallacy, sociobi- ology, survival, liberty, necessity, dearth, free will. INTRODUCTION Sociobiological theory deals with animal species that are “social”, that is, they form groups, develop a certain division of labor, and cooperate in order to survive in the struggle for existence. For this reason, these species appear from the start as if they were endowed with moral attributes. “Social” animals possess qualities comparable to human beings not only insofar they are born and die, develop, reproduce, become ill, nor since they relate to other beings of the same and even of other species, but because, as they perform all these various functions in their peculiar ways, they exhibit emotional and behavioral patterns curiously akin to those of human beings. One of the main sources of sociobiology is Darwinist theory which, upon refuting creationism and affirming the principle of continuity in the evolution of species, denies the existence of overall qualitative differences between human beings and higher animals (Darwin 1981, Part I, p. -

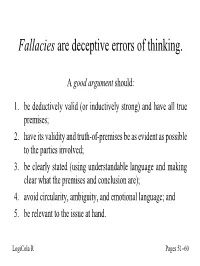

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Science for the People Magazine Vol. 4, No. 5

J NDIDE 4 LETTERS 6 SCIENCE TEACHING: TOWARDS AN ALTERNATIVE 11 UP AGAINST THE NST A 16 OBJECTING TO OBJECTIVITY: A COURSE IN BIOLOGY 22 RESOURCE BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 GRADING: TO EACH ACCORDING TO HER/HIS NEED? 29 ACTION AND REACTION: TEACHING PHYSICS IN CONTEXT 32 COMPUTER COURSE BIBLIOGRAPHY 34 A PRELIMINARY CRITIQUE OF THE PROJECT PHYSICS COURSE 36 HASTEN, JASON, GUARD THE NATION 40 CHAPTER REPORTS 46 LOCAL ADDRESSES 47 NEWS FROM VIETNAM VIA PARIS THAT WE DON'T GET FROM OUR PRESS EDITORIAL PRACTICE Each issue of Science for the People is prepared by a collective, assembled from volunteers by a committee made up of the collectives of the past calendar year. A collective carries out all editorial, production, and distribution functions for one issue. The following is a distillation of the actual practice of the past collectives. Due dates: Articles received by the first week of an odd-numbered month can generally be considered for the maga zine to be issued on the 15th of the next month. Form: One of the ways you can help is to submit double-spaced typewritten manuscripts with ·am ple margins. If you can send six copies, that helps even more. One of the few founding principles of SESPA is'that articles must be signed (a pseudo nym is acceptable). Criteria for acceptance: SESPA Newsletter, predecessor to Science for the People, was pledged to print everything submitted. It is no longer feasible to continue this policy, although the practice thus far has been to print all articles descriptive of SESPA/Science for the People activities. -

Moral Implications of Darwinian Evolution for Human Reference

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2006 Moral Implications of Darwinian Evolution for Human Reference Based in Christian Ethics: a Critical Analysis and Response to the "Moral Individualism" of James Rachels Stephen Bauer Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christianity Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Evolution Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Bauer, Stephen, "Moral Implications of Darwinian Evolution for Human Reference Based in Christian Ethics: a Critical Analysis and Response to the "Moral Individualism" of James Rachels" (2006). Dissertations. 16. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/16 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary MORAL IMPLICATIONS OF DARWINIAN EVOLUTION FOR HUMAN PREFERENCE BASED IN CHRISTIAN ETHICS: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS AND RESPONSE TO THE “MORAL INDIVIDUALISM” OF JAMES RACHELS A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Stephen Bauer November 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3248152 Copyright 2006 by Bauer, Stephen All rights reserved. -

The Ethics of Charles Darwin

teorema Vol. XXVIII/2, 2009, pp. 123-133 [BIBLID 0210-1602 (2009) 28:2; pp. 123-133] ‘The Social Instincts Naturally Lead to the Golden Rule’: The Ethics of Charles Darwin John Mizzoni […] the social instincts […] with the aid of active intellectual powers and the effects of habit, naturally lead to the golden rule, “As ye would that men should do to you, do ye to them likewise;” and this lies at the foundation of morality. [DARWIN, The Descent of Man (1871), p. 71] RESUMEN En The Descent of Man, Darwin discute una gran variedad de problemas éticos de manera exclusiva, dice él, desde la perspectiva de la historia natural. Intentando situar los puntos de vista de Darwin sobre la evolución y la ética dentro de las discusiones contemporáneas sobre filosofía moral reviso, en primer lugar, cómo el enfoque que Darwin hace de la evolución y la ética encaja en la metaética contemporánea, especialmente con cuatro teorías de tales como la del error, el expresi- vismo, el relativismo y el realismo. PALABRAS CLAVE: Darwin, metaética, teoría del error, expresivismo, relativismo moral, realismo moral. ABSTRACT In the The Descent of Man, Darwin discusses a wide variety of ethical issues, exclusively, he says, from the perspective of natural history. As an attempt to situate Darwin’s views on evolution and ethics into contemporary discussions of moral theory, in this paper I first look at how Darwin’s approach to evolution and ethics fits in with contemporary metaethical theory, specifically the four theories of error theory, expressivism, relativism, and realism. KEYWORDS: Darwin, metaethics, error theory, expressivism, moral relativism, moral realism.