Australia (1988)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategy-To-Win-An-Election-Lessons

WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 i The Institute of International Studies (IIS), Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is a research institution focused on the study on phenomenon in international relations, whether on theoretical or practical level. The study is based on the researches oriented to problem solving, with innovative and collaborative organization, by involving researcher resources with reliable capacity and tight society social network. As its commitments toward just, peace and civility values through actions, reflections and emancipations. In order to design a more specific and on target activity, The Institute developed four core research clusters on Globalization and Cities Development, Peace Building and Radical Violence, Humanitarian Action and Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. This institute also encourages a holistic study which is based on contempo- rary internationalSTRATEGY relations study scope TO and WIN approach. AN ELECTION: ii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 By Dafri Agussalim INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA iii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 Penulis: Dafri Agussalim Copyright© 2011, Dafri Agussalim Cover diolah dari: www.biogenidec.com dan http:www.foto.detik.com Diterbitkan oleh Institute of International Studies Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Gadjah Mada Cetakan I: 2011 x + 244 hlm; 14 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978-602-99702-7-2 Fisipol UGM Gedung Bulaksumur Sayap Utara Lt. 1 Jl. Sosio-Justisia, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281 Telp: 0274 563362 ext 115 Fax.0274 563362 ext.116 Website: http://www.iis-ugm.org E-mail: [email protected] iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revised version of my Master of Arts (MA) thesis, which was written between 1994-1995 in the Australian National University, Canberra Australia. -

JOSEPH MAX BERINSON B1932

THE LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA J S BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY Oral History Collection & THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENTARY ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Transcript of an interview with JOSEPH MAX BERINSON b1932 Access Research: Restricted until 1 January 2005 Publication: Restricted until 1 January 2005 Reference number 0H3102 Date of Interview 14 July 1993-7 July 1994 Interviewer Erica Harvey Duration 12 x 60 minute tapes Copyright Library Board of Western Australia The Library Board of WA 3 1111 02235314 6 INTRODUCTION This is an interview with Joseph (Joe) Berinson for the Battye Library and the Parliamentary Oral History Project. Joe Berinson was born to Sam Berinson and Rebecca Finklestein on 7 January 1932 in Highgate, Western Australia. He was educated at Highgate Primary School and Perth Modern School before gaining a Diploma of Pharmacy from the University of Western Australia in 1953. Later in life Mr Berinson undertook legal studies and was admitted to the WA Bar. He married Jeanette Bekhor in September 1958 and the couple have one son and three daughters Joining the ALP in 1953, Mr Berinson was an MHR in the Commonwealth Parliament from October 1969 to December 1975, where his service included Minister for the Environment from July to November 1975. In May 1980 he became an MLC in the Western Australian Parliament, where he remained until May 1989. Mr Berinson undertook many roles during his time in State Parliament, including serving as Attorney General from September 1981 to April 1983. The interview covers Mr Berinson's early family life and schooling, the migration of family members to Western Australia, and the influence and assistance of the Jewish community. -

Performing Arts Advocacy in Australia

Performing arts advocacy in Australia John Daley About the author A discussion paper commissioned by the Australian John Daley is one of Australia’s leading policy thinkers. He was Chief Executive Major Performing Arts Group of the Grattan Institute for its rst 11 years, and led it to become the leading This discussion paper was commissioned by the Australian Major Performing domestic policy think tank in Australia, publishing extensively on government Arts Group as its last substantial project. The members of AMPAG were given priorities, institutional reform, budget policy, and tax reform. the opportunity to comment on a draft of the discussion paper, but the author is responsible for its contents, and all remaining errors or omissions. He has 30 years’ experience spanning academic, government and corporate roles at the University of Melbourne, the University of Oxford, the Victorian This discussion paper was written by John Daley in his personal capacity. Bel Department of Premier and Cabinet, consulting rm McKinsey and Co, and Matthews and Bethwyn Serow provided research assistance for some aspects of ANZ Bank. the discussion paper. John is currently the Chair of the Australian National Academy of Music, which The author thanks for their extremely helpful contributions numerous members is one of the Arts8 performance training and education institutions that receive of Australia’s arts and culture community, in organisations, peak bodies, funds from the Commonwealth government. He is also a Director of the Myer government agencies, universities, and their personal capacity. Foundation. Previously, he was the Deputy Chair of the Malthouse Theatre, Deputy Chair of the Next Wave Festival, and the Chair of the Strategy and The paper is based on information available in April 2021. -

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-Funded Flights Taken by Former Mps and Their Widows Between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed in Descending Order by Number of Flights Taken

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-funded flights taken by former MPs and their widows between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed in descending order by number of flights taken NAME PARTY No OF COST $ FREQUENT FLYER $ SAVED LAST YEAR IN No OF YEARS IN FLIGHTS FLIGHTS PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT Ian Sinclair Nat, NSW 701 $214,545.36* 1998 25 Margaret Reynolds ALP, Qld 427 $142,863.08 2 $1,137.22 1999 17 Gordon Bilney ALP, SA 362 $155,910.85 1996 13 Barry Jones ALP, Vic 361 $148,430.11 1998 21 Graeme Campbell ALP/Ind, WA 350 $132,387.40 1998 19 Noel Hicks Nat, NSW 336 $99,668.10 1998 19 Dr Michael Wooldridge Lib, Vic 326 $144,661.03 2001 15 Fr Michael Tate ALP, Tas 309 $100,084.02 11 $6,211.37 1993 15 Frederick M Chaney Lib, WA 303 $195,450.75 19 $16,343.46 1993 20 Tim Fischer Nat, NSW 289 $99,791.53 3 $1,485.57 2001 17 John Dawkins ALP, WA 271 $142,051.64 1994 20 Wallace Fife Lib, NSW 269 $72,215.48 1993 18 Michael Townley Lib/Ind, Tas 264 $91,397.09 1987 17 John Moore Lib, Qld 253 $131,099.83 2001 26 Al Grassby ALP, NSW 243 $53,438.41 1974 5 Alan Griffiths ALP, Vic 243 $127,487.54 1996 13 Peter Rae Lib, Tas 240 $70,909.11 1986 18 Daniel Thomas McVeigh Nat, Qld 221 $96,165.02 1988 16 Neil Brown Lib, Vic 214 $99,159.59 1991 17 Jocelyn Newman Lib, Tas 214 $67,255.15 2002 16 Chris Schacht ALP, SA 214 $91,199.03 2002 15 Neal Blewett ALP, SA 213 $92,770.32 1994 17 Sue West ALP, NSW 213 $52,870.18 2002 16 Bruce Lloyd Nat, Vic 207 $82,158.02 7 $2,320.21 1996 25 Doug Anthony Nat, NSW 204 $62,020.38 1984 27 Maxwell Burr Lib, Tas 202 $55,751.17 1993 18 Peter Drummond -

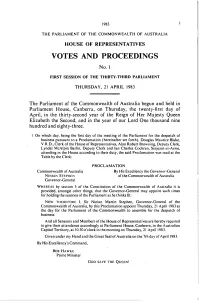

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1983 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT THURSDAY, 21 APRIL 1983 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Thursday, the twenty-first day of April, in the thirty-second year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and eighty-three. I On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Douglas Maurice Blake, V.R.D., Clerk of the House of Representatives, Alan Robert Browning, Deputy Clerk, Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Deputy Clerk and lan Charles Cochran, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION Commonwealth of Australia By His Excellency the Governor-General NINIAN STEPHIEN of the Commonwealth of Australia Governor-General WHEREAS by section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is provided, amongst other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now THEREFORE I, Sir Ninian Martin Stephen, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, by this Proclamation appoint Thursday, 21 April 1983 as the day for the Parliament of the Commonwealth to assemble for the despatch of business: And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, at 10.30 o'clock in the morning on Thursday, 21 April 1983. -

Votes and Proceedings

1969 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE TWENTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 25 NOVEMBER 1969 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the twenty-fifth day of November, in the eighteenth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and sixty-nine. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Alan George Turner, C.B.E., Clerk of the House of Representatives, Norman James Parkes, O.B.E., Deputy Clerk, John Athol Pettifer, Clerk Assistant, and Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION Commonwealth of By His Excellency the Governor-General in and over the Australia to wit Commonwealth of Australia. PAUL HASLUCK Governor-General. WHEREAS by the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is amongst other things provided that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, Sir Paul Meernaa Caedwalla Hasluck, the Governor-General aforesaid, in the exercise of the power conferred by the Constitution, do by this my Proclama- tion appoint Tuesday, the twenty-fifth day of November, One thousand nine hundred and sixty-nine, as the day for the Parliament to assemble and be holden for the despatch of divers urgent and important affairs: and all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly in the building known as Parliament House, Canberra, at the hour of eleven o'clock in the morning on the twenty-fifth day of November, One thousand nine hundred and sixty-nine. -

The Franklin River Debate 1983 1 Program Outline

Historic Parliamentary Role-play THE FRANKLIN RIVER A ready to use classroom resource for years 5–8 DEBATE 1983 Contents Program outline . 2. Program notes . 3–4. The debate . .5–20 Teacher background notes . 21–24. Resource list . 25 Website moad .gov .au THE FRANKLIN RIVER DEBATE 1983 1 Program outline The Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House traces democracy from its earliest origins and captivates visitors’ imagination through the stories of ordinary people using their voice to achieve extraordinary things . Old Parliament House, the home of the Australian Parliament from 1927 to 1988, has witnessed some of the most triumphant and turbulent events in Australia’s history . The culmination of one such event was the introduction of a federal bill in 1983 to stop the construction of a dam that would impact on the Franklin River . The Bill was listed as The World Heritage Properties Conservation Bill 1983 (Cwlth) . It was tabled by the newly elected Federal Labor Government in the House of Representatives . The debates were passionate . The Bill passed in the House of Representatives and the Senate . This Bill stopped the construction of a dam in a world heritage area . It established that the Federal Parliament had the power to overrule the States to conserve world heritage places . This debate explores State and Federal powers and the issue of world heritage places . The classroom program can be used as an introduction or conclusion to a unit on Federal Parliament or the environment . The program is flexible in application—it can be used as a one-off activity or extended to be a unit of work . -

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-Funded Flights Taken by Former Mps and Their Widows Between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed by Total Cost of All Flights Taken

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-funded flights taken by former MPs and their widows between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed by total cost of all flights taken NAME PARTY No OF COST $ FREQUENT FLYER $ SAVED LAST YEAR IN No OF YEARS IN FLIGHTS FLIGHTS PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT Ian Sinclair Nat, NSW 701 $214,545.36* 1998 25 Frederick M Chaney Lib, WA 303 $195,450.75 19 $16,343.46 1993 20 Gordon Bilney ALP, SA 362 $155,910.85 1996 13 Barry Jones ALP, Vic 361 $148,430.11 1998 21 Dr Michael Wooldridge Lib, Vic 326 $144,661.03 2001 15 Margaret Reynolds ALP, Qld 427 $142,863.08 2 $1,137.22 1999 17 John Dawkins ALP, WA 271 $142,051.64 1994 20 Graeme Campbell ALP/Ind, WA 350 $132,387.40 1998 19 John Moore Lib, Qld 253 $131,099.83 2001 26 Alan Griffiths ALP, Vic 243 $127,487.54 1996 13 Fr Michael Tate ALP, Tas 309 $100,084.02 11 $6,211.37 1993 15 Tim Fischer Nat, NSW 289 $99,791.53 3 $1,485.57 2001 17 Noel Hicks Nat, NSW 336 $99,668.10 1998 19 Neil Brown Lib, Vic 214 $99,159.59 1991 17 Janice Crosio ALP, NSW 154 $98,488.80 2004 15 Daniel Thomas McVeigh Nat, Qld 221 $96,165.02 1988 16 Martyn Evans ALP, SA 152 $92,770.46 2004 11 Neal Blewett ALP, SA 213 $92,770.32 1994 17 Michael Townley Lib/Ind, Tas 264 $91,397.09 1987 17 Chris Schacht ALP, SA 214 $91,199.03 2002 15 Peter Drummond Lib, WA 198 $87,367.77 1987 16 Ian Wilson Lib, SA 188 $82,246.06 6 $1,889.62 1993 24 Percival Clarence Millar Nat, Qld 158 $82,176.83 1990 16 Bruce Lloyd Nat, Vic 207 $82,158.02 7 $2,320.21 1996 25 Prof Brian Howe ALP, Vic 180 $80,996.25 1996 19 Nick Bolkus ALP, SA 147 $77,803.41 -

Scientific Advice, Traditional Practices and the Politics of Health-Care the Australian Debate Over Public Funding of Non-Therapeutic Circumcision, 1985

Scientific Advice, Traditional Practices and the Politics of Health-Care The Australian Debate over Public Funding of Non-Therapeutic Circumcision, 1985 Robert Darby ustralia is unusual among comparable developed nations in providing automatic coverage for non-therapeutic circumcision of male infants and Aboys through a nationally funded health insurance system. This is despite at least one attempt to drop circumcision from the schedule of benefits payable under the scheme (now known as Medicare), and it is surprising given that relevant health authorities have repeatedly stated (1971, 1983, 1996, 2002, 2004 and 2010) that ‘routine’ circumcision has no valid medical indication and should not generally be performed. Since public hospitals in most states do not provide the surgery, it has become the province of private hospitals, general practitioners and, in recent years, specialist clinics, whose activities are subsidised through Medicare. Australian practice is thus very different from that in comparable countries. In New Zealand the government health service has never funded circumcision; and in Canada it is funded only in the province of Manitoba.1 Even in the United States, where policy on Medicaid coverage is also the responsibility of the states, 17 out of the 50 have dropped circumcision from the list of free procedures, and more are likely to do so as fiscal constraints intensify.2 The British National Health Service has traditionally not covered non-therapeutic circumcision, though in recent times has come under pressure from Muslim and some African immigrant groups, who argue that publicly funded circumcision of their male children is essential to pre- vent parents from resorting to the services of incompetent operators. -

A Dissident Liberal

A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME PETER BAUME Edited by John Wanna and Marija Taflaga A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Baume, Peter, 1935– author. Title: A dissident liberal : the political writings of Peter Baume / Peter Baume ; edited by Marija Taflaga, John Wanna. ISBN: 9781925022544 (paperback) 9781925022551 (ebook) Subjects: Liberal Party of Australia. Politicians--Australia--Biography. Australia--Politics and government--1972–1975. Australia--Politics and government--1976–1990. Other Creators/Contributors: Taflaga, Marija, editor. Wanna, John, editor. Dewey Number: 324.294 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press CONTENTS Foreword . vii Introduction: A Dissident Liberal—A Principled Political Career . xiii 1 . My Dilemma: From Medicine to the Senate . 1 2 . Autumn 1975 . 17 3 . Moving Towards Crisis: The Bleak Winter of 1975 . 25 4 . Budget 1975 . 37 5 . Prelude to Crisis . 43 6 . The Crisis Deepens: October 1975 . 49 7 . Early November 1975 . 63 8 . Remembrance Day . 71 9 . The Election Campaign . 79 10 . Looking Back at the Dismissal . 91 SPEECHES & OTHER PRESENTATIONS Part 1: Personal Philosophies Liberal Beliefs and Civil Liberties (1986) . -

Prime Ministers at the Australian National University: an Archival Guide

PRIME MINISTERS AT THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY An Archival Guide PRIME MINISTERS AT THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY An Archival Guide Michael Piggott & Maggie Shapley Published by ANU eView The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://eview.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Piggott, Michael, 1948- Title: Prime ministers at the Australian National University : an archival guide / Michael Piggott & Maggie Shapley. ISBN: 9780980728446 (pbk.) 9780980728453 (pdf) Subjects: Australian National University. Noel Butlin Archives Centre. Prime ministers--Australia--Archives. Australia--Politics and government--Archival resources. Other Authors/Contributors: Shapley, Maggie. Dewey Number: 994.04092 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Book design and layout by Teresa Prowse, www.madebyfruitcup.com Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU eView Research for this publication was supported by the Australian Government under an Australian Prime Ministers Centre Fellowship, an initiative of the Museum of Australian Democracy Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix 1. Prime Ministers and the ANU 1 Earliest links 2 The war and its aftermath 4 Students, staff, and other connections 8 The collection connection – official documents 12 The collection connection – Butlin 13 2. Prime Ministers in the archival landscape 17 Papers of or about prime ministers 17 Prime ministers without papers 19 What’s relevant? 20 Personal papers of prime ministers 21 Archives about prime ministers 22 Prime ministerial libraries 23 The prime ministers’ portal 24 The Australian Prime Ministers Centre 26 The ANU collection 26 3. -

Federal Labor in Opposition

In the Wilderness: Federal Labor in Opposition Author Lavelle, Ashley Published 2004 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Politics and Public Policy DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1005 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366181 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au IN THE WILDERNESS: FEDERAL LABOR IN OPPOSITION Ashley Lavelle BComm (Hons) (Griffith University) Presented to the Faculty of International Business and Politics Griffith University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2003 Abstract This thesis is a study of the federal Australian Labor Party (ALP) in Opposition. It seeks to identify the various factors that shape the political direction of the party when it is out of office by examining three important periods of Labor Opposition. It is argued in the first period (1967-72) that the main factor in the party’s move to the left was the radicalisation that occurred in Australian (and global) politics. Labor in Opposition is potentially more subject to influence by extra-parliamentary forces such as trade unions and social movements. This was true for this period in the case of the reinvigorated trade union movement and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement, whose policy impacts on the ALP under Gough Whitlam are examined in detail. While every one of the party’s policies cannot be attributed to the tumult of the period, it is argued that Labor’s Program embodied the mood for social change. The second period (1975-83) records a much different experience.