What He Has Seen and the People He Has Met in the Course of the Last Forty Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategy and Geopolitics of Sea Power Throughout History

Baltic Security & Defence Review Volume 11, Issue 2, 2009 Strategy and Geopolitics of Sea Power throughout History By Ilias Iliopoulos PhD, Professor at the Hellenic Staff College The great master of naval strategy and geopolitics Rear-Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan famously stated: “Control of the sea by maritime commerce and naval supremacy means predominant influence in the world … (and) is the chief among the merely material elements in the power and prosperity of nations.”1 Some three centuries before Mahan, H. M.’s Servant Sir Walter Raleigh held that “he that commands the sea, commands the trade, and he that is lord of the trade of the world is lord of the wealth of the world.”2 Accordingly, it may be said that even the final collapse of the essentially un-maritime and land-bound Soviet empire at the end of the long 20th century was simply the latest illustration of the strategic advantages of sea power. Like most realist strategists Mahan believed that international politics was mainly a struggle over who gets what, when and how. The struggle could be about territory, resources, political influence, economic advantage or normative interests (values). The contestants were the leaders of traditional nation-states; military and naval forces were their chief instrument of policy. Obviously, sea power is about naval forces – and coastguards, marine or civil-maritime industries and, where relevant, the contribution of land and air forces. Still, it is more than that; it is about geography, geopolitics, geo- strategy, geo-economics and geo-culture; it is about the sea-based capacity of a state to determine or influence events, currents and developments both at sea and on land. -

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan's Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/32d241sf Author Perelman, Elisheva Avital Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Professor John Lesch Professor Alan Tansman Fall 2011 © Copyright by Elisheva Avital Perelman 2011 All Rights Reserved Abstract The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Tuberculosis existed in Japan long before the arrival of the first medical missionaries, and it would survive them all. Still, the epidemic during the period from 1890 until the 1920s proved salient because of the questions it answered. This dissertation analyzes how, through the actions of the government, scientists, foreign evangelical leaders, and the tubercular themselves, a nation defined itself and its obligations to its subjects, and how foreign evangelical organizations, including the Young Men’s Christian Association (the Y.M.C.A.) and The Salvation Army, sought to utilize, as much as to assist, those in their care. -

Joseph Heco and the Origin of Japanese Journalism*

Journalism and Mass Communication, Mar.-Apr. 2020, Vol. 10, No. 2, 89-101 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2020.02.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Joseph Heco and the Origin of Japanese Journalism* WANG Hai, YU Qian, LIANG Wei-ping Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China Joseph Heco, with the original Japanese name of Hamada Hikozo, played an active role in the diplomatic, economic, trade, and cultural interactions between the United States and Japan in the 1850s and 1860s. Being rescued from a shipwreck by an American freighter and taken to San Francisco in the 1850s, Heco had the chance to experience the advanced industrial civilization. After returning to Japan, he followed the example of the U.S. newspapers to start the first Japanese newspaper Kaigai Shimbun (Overseas News), introducing Western ideas into Japan and enabling Japanese people under the rule of the Edo bakufu/shogunate to learn about the great changes taking place outside the island. In the light of the historical background of the United States forcing Japan to open up, this paper expounds on Joseph Heco’s life experience and Kaigai Shimbun, the newspaper he founded, aiming to explain how Heco, as the “father of Japanese journalism”, promoted the development of Japanese newspaper industry. Keywords: Joseph Heco (Hamada Hikozo), Kaigai Shimbun, origin of Japanese journalism Early Japanese newspapers originated from the “kawaraban” (瓦版) at the beginning of the 17th century. In 1615, this embryonic form of newspapers first appeared in the streets of Osaka. This single-sided leaflet-like thing was printed irregularly and was made by printing on paper with tiles which was carved with pictures and words and then fired and shaped. -

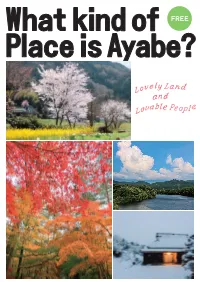

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

Wars Between the Danes and Germans, for the Possession Of

DD 491 •S68 K7 Copy 1 WARS BETWKEX THE DANES AND GERMANS. »OR TllR POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. BV t>K()F. ADOLPHUS L. KOEPPEN FROM THE "AMERICAN REVIEW" FOR NOVEMBER, U48. — ; WAKS BETWEEN THE DANES AND GERMANS, ^^^^ ' Ay o FOR THE POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. > XV / PART FIRST. li>t^^/ On feint d'ignorer que le Slesvig est une ancienne partie integTante de la Monarchie Danoise dont I'union indissoluble avec la couronne de Danemarc est consacree par les garanties solennelles des grandes Puissances de I'Eui'ope, et ou la langue et la nationalite Danoises existent depuis les temps les et entier, J)lus recules. On voudrait se cacher a soi-meme au monde qu'une grande partie de la popu- ation du Slesvig reste attacliee, avec une fidelite incbranlable, aux liens fondamentaux unissant le pays avec le Danemarc, et que cette population a constamment proteste de la maniere la plus ener- gique centre une incorporation dans la confederation Germanique, incorporation qu'on pretend medier moyennant une armee de ciuquante mille hommes ! Semi-official article. The political question with regard to the ic nation blind to the evidences of history, relations of the duchies of Schleswig and faith, and justice. Holstein to the kingdom of Denmark,which The Dano-Germanic contest is still at the present time has excited so great a going on : Denmark cannot yield ; she has movement in the North, and called the already lost so much that she cannot submit Scandinavian nations to arms in self-defence to any more losses for the future. The issue against Germanic aggression, is not one of a of this contest is of vital importance to her recent date. -

Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D

issn 0304-1042 Japanese Journal of Religious Studies volume 47, no. 1 2020 articles 1 Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D. McMullen 11 Buddhist Temple Networks in Medieval Japan Daigoji, Mt. Kōya, and the Miwa Lineage Anna Andreeva 43 The Mountain as Mandala Kūkai’s Founding of Mt. Kōya Ethan Bushelle 85 The Doctrinal Origins of Embryology in the Shingon School Kameyama Takahiko 103 “Deviant Teachings” The Tachikawa Lineage as a Moving Concept in Japanese Buddhism Gaétan Rappo 135 Nenbutsu Orthodoxies in Medieval Japan Aaron P. Proffitt 161 The Making of an Esoteric Deity Sannō Discourse in the Keiran shūyōshū Yeonjoo Park reviews 177 Gaétan Rappo, Rhétoriques de l’hérésie dans le Japon médiéval et moderne. Le moine Monkan (1278–1357) et sa réputation posthume Steven Trenson 183 Anna Andreeva, Assembling Shinto: Buddhist Approaches to Kami Worship in Medieval Japan Or Porath 187 Contributors Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 47/1: 1–10 © 2020 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture dx.doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.47.1.2020.1-10 Matthew D. McMullen Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan he term “esoteric Buddhism” (mikkyō 密教) tends to invoke images often considered obscene to a modern audience. Such popular impres- sions may include artworks insinuating copulation between wrathful Tdeities that portend to convey a profound and hidden meaning, or mysterious rites involving sexual symbolism and the summoning of otherworldly powers to execute acts of violence on behalf of a patron. Similar to tantric Buddhism elsewhere in Asia, many of the popular representations of such imagery can be dismissed as modern interpretations and constructs (White 2000, 4–5; Wede- meyer 2013, 18–36). -

Round the World by Andrew Carnegie</H1>

Round the World by Andrew Carnegie Round the World by Andrew Carnegie Produced by Paul Wenker, Kurt Hockenbury and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. ROUND THE WORLD BY ANDREW CARNEGIE PREFACE It seems almost unnecessary to say that "Round the World," like "An American Four-in-Hand in Britain," was originally printed for private circulation. My publishers having asked permission to give it to the public, I have been induced to undertake the slight revision, and to make some additions necessary to fit the original for general circulation, not so much by the favorable reception accorded to the "Four-in-Hand" in England as well as in America, nor even by the flattering words of the critics who have dealt so kindly with it, but chiefly because of many valued letters which page 1 / 342 entire strangers have been so extremely good as to take the trouble to write to me, and which indeed are still coming almost daily. Some of these are from invalids who thank me for making the days during which they read the book pass more brightly than before. Can any knowledge be sweeter to one than this? These letters are precious to me, and it is their writers who are mainly responsible for this second volume, especially since some who have thus written have asked where it could be obtained and I have no copies to send to them, which it would have given me a rare pleasure to be able to do. I hope they will like it as they did the other. Some friends consider it better; others prefer the "Four-in-Hand." I think them different. -

Estate Landscapes in Northern Europe: an Introduction

J Estate Landscapes in northern Europe an introduction By Jonathan Finch and Kristine Dyrmann This volume represents the first transnational exploration of the estate Harewood House, West Yorkshire, landscape in northern Europe. It brings together experts from six coun- UK Harewood House was built between tries to explore the character, role and significance of the estate over five /012 and /00/ for Edwin Lascelles, whose family made their fortune in the West hundred years during which the modern landscape took shape. They do Indies. The parkland was laid out over so from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds, to provide the first critical the same period by Lancelot ‘Capability’ study of the estate as a distinct cultural landscape. The northern European Brown and epitomizes the late-eighteenth countries discussed in this volume – Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, century taste for a more informal natural- the Netherlands and Britain – have a fascinating and deep shared history istic landscape. Small enclosed fields from of cultural, economic and social exchange and dialogue. Whilst not always the seventeenth century were replaced by a family at peace, they can lay claim to having forged many key aspects of parkland that could be grazed, just as it is the modern world, including commercial capitalism and industrialization today, although some hedgerow trees were retained to add interest within the park, from an overwhelmingly rural base in the early modern period. United such as those in the foreground. By the around the North Sea, the region was a gateway to the east through the early-nineteenth century all arable culti- Baltic Sea, and across the Atlantic to the New World in the west. -

Studia Podlaskie T 16

STUDIA PODLASKIE tom XIX BIAŁYSTOK 2011 KRYSTYna SzeLągowska Białystok O tym, Jak pani Lykke Z Chłopami i krÓlem woJowała, CZyli o kobieCie interesu W XVI-wieCZneJ Danii–NorweGii „(-) i wreszcie wygłosiła – całkowicie nieprawdziwą – uwagę, która w uszach króla Chrystiana musiała zabrzmieć szczególnie irytująco, uwagę bliską polskie- mu liberum veto, która w każdym państwie, opartym na monarchicznej zasadzie musiała wydać się zagrożeniem dla porządku społecznego: stwierdziła bowiem, że «nie wiem, ani nie słyszałam, by cała szlachta zebrała się i zatwierdziła ten reces; a to należy się szlachcie wedle jej wolności i przysięgi, jaką jej [król] złożył»”1. Tak pod koniec XIX w. o rozprawie, która odbyła się w 1556 r. przed sądem duńskiego króla Chrystiana III pisał duński historyk Gustaw Bang. Osobą, która wypowie- działa przytoczone słowa, powołując się na szlacheckie wolności, słowa, które Bangowi skojarzyły się z systemem panującej w Rzeczypospolitej demokracji szla- checkiej, była Sophie Lykke, duńska szlachcianka, która, jak twierdzą biografowie, okazała się kłopotliwą poddaną dwóch kolejnych duńskich władców w 2. połowie XVI w., zarówno kiedy mieszkała w Danii, jak i Norwegii. O pani Lykke pisali w różnych opracowaniach duńscy i norwescy biografo- wie. W pierwszym, pochodzącym z końca XIX w., wydaniu duńskiego słownika biograficznego pod redakcją Carla Frederika Bricki, autorem jej biogramu był Anders Thiset2, we współczesnym, trzecim wydaniu – napisała go Astrid Friis3. 1 G. Bang, Fru Sophie Lykke, en Adelsdame i det 16. Aarhundrede, „Museum. Tidsskrift for Historie og Geografi”, R. 1894, t. 2, Kjøbenhavn. 2 A. Thiset, Sophie Lykke, [biogram w:] Dansk Biografisk Lexikon, red. C. F. Bricka, t. 10, Kjøbenhavn 1896, s. 523-525. -

The Giraffe in History and Art

The Giraffe in History and Art BY BERTHOLD LAUFER Curator of Anthropology 9 Plates in Photogravure, 23 Text-figures, and 1 Vignette Anthropology Leaflet 27 FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CHICAGO 1928 The Anthropological Leaflets of Field Museum are designed to give brief, non-technical accounts of some of the more interesting beliefs, habits and customs of the races whose life is illustrated in the Museum's exhibits. LIST OF ANTHROPOLOGICAL LEAFLETS ISSUED TO DATE 1. The Chinese Gateway (Laufer) . ... $.10 2. The Philippine Forge Group (Cole) 10 3. The Japanese Collections (Gunsaulus) 25 4. New Guinea Masks (Lewis) 25 5. The Thunder Ceremony of the Pawnee (Linton) . .25 6. The Sacrifice to the Morning Star by the Skidi Pawnee (Linton) 10 7. Purification of the Sacred Bundles, a Ceremony of the Pawnee (Linton) 10 8. Annual Ceremony of the Pawnee Medicine Men (Linton) 10 9. The Use of Sago in New Guinea (Lewis) 10 10. Use of Human Skulls and Bones in Tibet (Laufer) .10 11. The Japanese New Year's Festival, Games and Pastimes (Gunsaulus) 25 12. Japanese Costume (Gunsaulus) 25 13. Gods and Heroes of Japan (Gunsaulus) 25 14. Japanese Temples and Houses (Gunsaulus) . .25 15. Use of Tobacco among North American Indians (Linton) 25 16. Use of Tobacco in Mexico and South America (Mason) 25 17. Use of Tobacco in New Guinea (Lewis) 10 18. Tobacco and Its Use in Asia (Laufer) 25 19. Introduction of Tobacco into Europe (Laufer) . .25 20. The Japanese Sword and Its Decoration . (Gunsaulus) 25 in . 21. Ivory China (Laufer) , 75 22.