Digital Technologies and Artificial Intelligence's Present And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2021 Schedule of Classes, Rev 5/24/21

Find the most UPDATED LIST OF CLASSES in the online searchable schedule at WLAC.edu 2021 Fall Classes You’re invited to attend Information Sessions about our programs of study…see calendar FALL 2021 CLASSES: GETTING STARTED Online Searchable Schedule How to Get Started: Video Instructions | Written Instructions | Enrollment Workshop Sign Up Other Admissions Information Questions? Email: [email protected] Call: (424) 371-7734 Live Chat Dates to Know Free College Session Period Aug 30 – Dec 19 • Through the College & Career Division, you can 8-Week Sessions: Aug 30 – Oct 24 take free classes that prepare you to succeed in Oct 25 – Dec 19 math, English and other classes (BSICSKL, VOC ED) • Prepare for the GED or improve your English (ESL) • Priority Enrollment Begins ................. May 24 • Earn college credit for your job or internship • Open Enrollment Begins ................... June 18 • Complete job programs that take less than 1 year • How to find your registration date and get job success skills • FINAL EXAMS SCHEDULE................. PAGE 4 Page 1 - rev 5/27/21 WLAC $0 Tuition Promise Program Orientation Workshops West’s LA College Promise (LACP) program provides FREE TUITION to first-time freshmen of any age and income that commit to full-time enrollment. Participants also earn priority registration and support vouchers for transportation, books, or dining at the Wildcat Café. Are you ready to join LACP? Attend this orientation session to: Learn about the LA College Promise program requirements Explore learning and career pathways Review wrap-around services, student support programs, the career connections center, and more! Register at BIT.LY/WLAC-LACP Follow us on Instagram @wlacoutreach or visit bit.ly/wlac-freshmen for more information. -

Downloads.” International Review of Law, Computers and Technology, 15, No

Nova Southeastern University From the SelectedWorks of Pearl Goldman 2008 Legal Education and Technology II: An Annotated Bibliography Pearl Goldman Available at: https://works.bepress.com/pearl_goldman/10/ Legal Education and Technology II: An Annotated Bibliography* Pearl Goldman** The digital revolution in legal education has engendered a large body of scholarship. To help legal educators locate materials that inform and enrich their teaching and writing, Professor Goldman offers an updated annotated bibliography of articles, commentaries, conference papers, essays, books, and book chapters that examine the impact of technology on legal education. Introduction. .416 Acronyms. 417 Bibliography. 418 Specific Technologies. .418 Communications Technology. 418 Information Technology . 419 Instructional Technology. 423 Artificial Intelligence. 423 Electronic Course Materials. .427 Film and Television. 436 Presentation Technology. 438 Simulations and Games. 440 Tutorials (CAI or CAL). 442 Miscellaneous Instructional Technologies. 444 Curriculum. 446 Clinical Legal Education. 446 Doctrinal Courses. 447 Skills Courses and Programs. 453 Distance Education and Distance Learning. .466 Pedagogy . 476 Law Schools. .482 Administrative Considerations. .482 Law Faculty. 483 Law Libraries and Librarians. 487 * © Pearl Goldman, 2008 ** Professor of Law, Nova Southeastern University Shepard Broad Law Center, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The author expresses gratitude to Maxine Scheffler for her interlibrary loan efforts, to Mary Paige Smith and Carol Yecies -

Documents on Display

Annual Report 2011 on Form 20-F Annual Report 2011 on Form 20-F As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 12, 2012 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) or 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Or Í ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2011 Or ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Or ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 1-3334 REED ELSEVIER PLC REED ELSEVIER NV (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) England The Netherlands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) 1-3 Strand, London, WC2N 5JR, England Radarweg 29, 1043 NX, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (Address of principal executive offices) (Address of principal executive offices) Henry Udow Jans van der Woude Company Secretary Company Secretary Reed Elsevier PLC Reed Elsevier NV 1-3 Strand, London, WC2N 5JR, England Radarweg 29, 1043 NX, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 011 44 20 7930 7077 011 31 20 485 2222 [email protected] [email protected] (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address -

Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form 20-F

169724 20-F Cover_v2.qxd 7/3/07 16:00 Page 1 > www.reedelsevier.com Reed Elsevier Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 22, 2007 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) n REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) or 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Or ¥ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2006 Or n TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Or n SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 1-3334 REED ELSEVIER PLC REED ELSEVIER NV (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) England The Netherlands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) 1-3 Strand Radarweg 29 London WC2N 5JR 1043 NX Amsterdam England The Netherlands (Address of principal executive offices) (Address of principal executive offices) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of exchange on which Title of each class registered Reed Elsevier PLC: American Depositary Shares (each representing four Reed Elsevier PLC ordinary shares) New York Stock Exchange Ordinary shares of 12.5p each (the ""Reed Elsevier PLC ordinary shares'') New York Stock Exchange* Reed Elsevier NV: American Depositary Shares (each representing two Reed Elsevier NV ordinary shares) New York Stock Exchange Ordinary shares of 40.06 each (the ""Reed Elsevier NV ordinary shares'') New York Stock Exchange* * Listed, not for trading, but only in connection with the listing of the applicable Registrant's American Depositary Shares issued in respect thereof. -

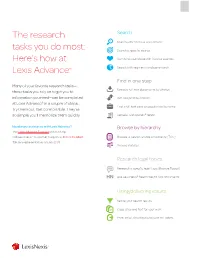

The Research Tasks You Do Most: Here's How at Lexis Advance®

The research Search Search with “terms & connectors” tasks you do most: Search a specific source Here’s how at Combine sources/search favorite sources Lexis Advance® Search with segments and commands Find in one step Many of your favorite research tasks— Retrieve full-text documents by citation those tasks you rely on to get you to information you need—can be completed Get and print by citation at Lexis Advance® in a couple of steps. Find a full-text case or popular law by name Try them out. Get comfortable. They’re so simple you’ll memorize them quickly. Request a Shepard’s® report Need more assistance with Lexis Advance? Browse by hierarchy The Lexis Advance Support site can help. Call LexisNexis® Customer Support at 800-543-6862. Browse or search a table of contents (TOC) Talk to a representative virtually 24/7. Browse statutes Research legal topics Research a specific legal topic (Browse Topics) Use LexisNexis® headnotes to find documents Using/delivering results Refine your search results Copy cites and text for your work Print, email, download and save to Folders Search Search with “terms & connectors” Combine sources/search favorite sources To combine sources: 1. Enter a partial source name in the red search box. The word wheel will make suggestions. Select a source. 2. Repeat to add more sources to your search. The source combination is saved automatically in Recent & Favorites. Just enter your words and connectors in the red search box, e.g., same sex! W/10 marriage, and select Search. Lexis Advance View recent searches and create Favorites: automatically interprets search commands such as ! and * • Select the Filters pull-down menu in the red search box to truncate words and W/n, OR, AND, etc. -

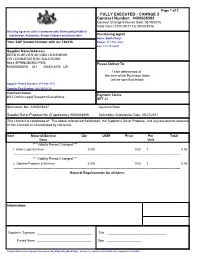

CHANGE 3 Contract Number: 4400008393

Page 1 of 2 FULLY EXECUTED - CHANGE 3 Contract Number: 4400008393 Contract Change Effective Date: 05/18/2016 Valid From: 07/01/2011 To: 09/30/2016 All using Agencies of the Commonwealth, Participating Political Subdivision, Authorities, Private Colleges and Universities Purchasing Agent Name: Barth Cheryl Your SAP Vendor Number with us: 166416 Phone: 717-703-2934 Fax: 717-783-6241 Supplier Name/Address: REED ELSEVIER INC DBA LEXISNEXIS OR LEXISNEXIS RISK SOLUTIONS 9443 SPRINGBORO PIKE Please Deliver To: MIAMISBURG OH 45342-4425 US To be determined at the time of the Purchase Order unless specified below. Supplier Phone Number: 678-694-3976 Supplier Fax Number: 866-960-4770 Contract Name: Payment Terms 8012 Online Legal Research/LexisNexis NET 30 Solicitation No.: 6100018237 Issuance Date: Supplier Bid or Proposal No. (if applicable): 6500038896 Solicitation Submission Date: 05/27/2011 This contract is comprised of: The above referenced Solicitation, the Supplier's Bid or Proposal, and any documents attached to this Contract or incorporated by reference. Item Material/Service Qty UOM Price Per Total Desc Unit *** Validity Period Changed *** 1 Basic Legal Services 0.000 0.00 1 0.00 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- *** Validity Period Changed *** 2 Optional Products & Services 0.000 0.00 1 0.00 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

The Lawyers Weekly, the Subscribe to Lawyers to Visit

Up to 6 Months Free for New Subscribers!* Lexis Advance® Quicklaw® A superior legal search solution with an intuitive interface. Done. Exceptional content, exclusive insights and time- saving tools. Done. Get it done for your firm, free for up to 6 months.* Contact us today! 1-877-851-7661 lexisnexis.ca/6months A Canadian Bar Association Preferred Supplier *Offer ends February 29, 2016. Available for new Lexis Advance Quicklaw subscribers only. New customers signing a 12-month contract with receive 2 additional months of free access. New customers signing a 24-month contract will receive an additional 4 months of free access. New customers signing a 36-month contract will receive an additional 6-month of free access. Offer cannot be combined with any other promotion. Terms and conditions apply. LexisNexis and the Knowledge Burst logo are registered trademarks of Reed Elsevier Properties Inc., used under licence. Lexis Advance, Quicklaw and QuickCITE are registered trademarks of LexisNexis Canada Inc. Other products or services may be trademarks, registered trademarks, service marks of their respective companies. © 2016 LexisNexis Canada Inc. All rights reserved. BE PREPARED for your litigation needs with DOCUdavit’s Litigation Support Services. Scan, Index, Store, Retrieve and e-Discovery. Call DOCUdavit Solutions 1-888-781-9083 and Be Prepared. e: [email protected] www.docudavit.com Vol. 35, No. 37 FEBRUARY 12, 2016 lawyersweekly.ca Landmark Nation ‘can and must do better’ tort creation say ministers of child treatment worries some -

Newsletter Nov 2004 Vol 15 No 4

Page 1 November 2004 NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER OSALL Vol. 15 No. 4 November 2004 Organisation of SA Law Libraries "OSALL aims to link and support everyone interested in Law Librarianship in South Africa" P.O. Box 783779, Sandton 2146 To access our website: http://sunsite.wits.ac.za/osall Editorial OSALL Committee Members The December issue has many interesting articles, for you to enjoy over the festive season. Carol Clark’s Danielle Heij (Chair) account of her trip to Helsinki, to attend the IALL Tel. (011) 242 8016 Conference is most interesting, as is our holiday article, E-mail: [email protected] by Salome Vranas, of her wonderful trip to the recent Olympic Games. We thought it would be fun to include Mzoxolo Gulwa (Vice-Chair) some light reading, of special holidays enjoyed by Tel. (011) 710-6205 OSALL members, in our November issue. It will help E-mail: [email protected] us go into “chill” mode, over the holiday period. Rika van der Walt (Secretary) I have also been fortunate, in being able to reprint an Tel. (012) 351-0872 article by Mary Ellen Bates, on specialised search E-mail: [email protected] engine, which will interest many readers. The second part of an article by Dennis Kennedy, on Legal Selma Savitz (Treasurer) Technology Trends 2004, is also included. Nico Tel. 083 628 8757 Ferreira’s regular “Publications Noted” includes some E-mail: [email protected] websites that are worth a visit. Thank you to my colleagues, Charmaine Bertram and Salome Vranas, Lydia Craemer (Listserv Administrator) for their assistance with the newsletter. -

Corporate Responsibility Report 2009 Summary Chief Executive’S Introduction Governance People and Community and People Customers

Corporate Responsibility Report 2009 Summary Chief Executive’s introduction Governance People and community Customers I believe corporate responsibility is good for business and it is good for Reed Elsevier. It means employing the highest ethical standards in everything we do and helping society by using our unique expertise to progress science and improve global health, advance the rule of law and prevent crime, and broaden access to information. Health and safety Corporate responsibility involves providing our customers with exceptional service and leading information and tools that enable them to make critical decisions, enhance productivity, and improve outcomes. It also means treating our employees fairly and inspiring them to reach their full potential, while making a significant contribution to the communities where we live and work. It requires us to further best practice in our supply chain, and limit our impact on the environment, while spurring knowledge and debate through Supply chain our environmental publications and expertise. In the pages that follow, you can find our 2009 corporate responsibility objectives, our performance against them, and future plans. We highlight progress, such as reaching our goal to train 80% of staff in our Code of Ethics and Business Conduct and indicate where we must take greater action, like reducing energy consumption at our data centres. The report details our emphasis on stakeholder engagement, our aim to lead by example, and our Environment support for initiatives that advance good corporate behaviour like the UN Global Compact with its ten core principles in human rights, labour, the environment, and anti-bribery. Despite challenging economic conditions in our markets, our commitment to corporate responsibility has not waned. -

FAILING FOIA SYSTEM HOW YOU CAN GET a GRIP on YOUR Rfis

RESPONDING TO INFORMATION REQUESTS IN A FAILING FOIA SYSTEM HOW YOU CAN GET A GRIP ON YOUR RFIs Agencies and citizens alike are suffering major headaches with each request for information piled onto the heap. These skyrocketing numbers represent a change in the information landscape. 800,000 713,168 This is the number of new RFIs government received in 2015, while simultaneously processing an unprecedented 770,000 backlogged B 750,000 requests during the same fiscal year.1 F B- 700,000 C D- 650,000 2/3 C- 600,000 550,000 D D+ 500,000 2 21 211 212 21 21 21 94% 10 out of the 15 most requested $480,235,968 Processing of requests & repeals agencies are ranked below a C-, a failing This is the total cost of FOIA-related 6% grade, in terms of FOIA compliance:2 activities across government in 2015.1 Litigation-related activities Government agencies are dealing with INQUIRIES ARE AGENCIES ARE more data than ever. Continuing in this way puts government agencies’ efficiency, STOCKPILING STRUGGLING pocketbooks and reputations at risk. Ordinarily, the FOIA workflow looks like this ... PROCESS THE REQUEST REVIEW AND REDACT PRODUCE THE RECORD Responding to an incoming request starts Social Security Numbers, names, phone numbers When data has been located and subjected with the main culling and vetting for validity and email addresses are just a few pieces of to adequate review, it must be endorsed that happens after a request has been information that need to be meticulously redacted and delivered to the requester in the made. -

Without Complications

Litigation Solutions COMPLIANCE WITHOUT COMPLICATIONS: FOIASOFTWARE SOLUTIONS FROM LEXISNEXIS Complying with the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) is critical to the success of our democracy. But having an understanding and appreciation of open government does not change the fact that complying with these mandates is incredibly time and cost intensive. LEXISNEXIS.COM/LITIGATION The Department of Justice Summary of Annual FOIA Reports for Fiscal Year 2015 found that: • The 100 agencies subject to FOIA transparency requirements received more than 713,168 requests in fiscal 2015 while processing “a record high number of nearly 770,000 requests.” • During the 2015 fiscal year, FOIA administration required 4,122 full-time staff members. • The total estimated cost of all FOIA-related activities across government during 2015 was $480,235,968. • Nearly 94 percent of the total cost was attributed to the processing of requests and appeals by agencies, with only 6 percent going to litigation. These numbers are driven by the fact that FOIA requests are not limited to parties involved in a particular case. Anyone may make a request without having to disclose why they need the information. Additionally, government agencies must comply with amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedures (FRCP), which require precise recordkeeping in regard to electronic discovery process, so any Freedom of Information Act documents used in civil cases must comply with this regulation. With a long history of developing solutions for eDiscovery, LexisNexis® is here to help. We work with agencies to apply the right mix of technologies to meet the challenge of responding to FOIA requests. -

THE CHALLENGE of INNOVATION in LAW the CHALLENGE Do Occur, in Doctrine, in Procedure, in Jurisprudential Understanding, and in Legal Education

Law is changing. Although both specialists and society as a whole often act as if it is an un-changing 1 monolith, any rational commentator must note that it has evolved over time. Changes (Eds) TOMASI OLIVER R. GOODENOUGH and MARTA AMEDEO SANTOSUOSSO, IN LAW THE CHALLENGE OF INNOVATION THE CHALLENGE do occur, in doctrine, in procedure, in jurisprudential understanding, and in legal education. The factors which drive innovation in law include social transformation, cultural change, and, importantly, the technological possibilities of the times for creating, storing and applying legal information. New technologies can also require new OF INNOVATION doctrinal developments. Such changes often do not come easily for the legal system. The myth of stability is maintained in part because the acceptance by the public rests on this assumption. It remains a myth, nonetheless. IN LAW The impact of innovation on law is clearly two-fold: on the one side, innovation invests the way law is created, managed, and applied. On the other side, the emersion of new technologies calls for a reshaping of existing legal norms in specific fields. The Impact of Technology and Science The book is divided into two parts. The first one offers a general overview on the on Legal Studies and Practice systemic technologically-driven change law is going to face in the next few years. In the second part, issues like robotics, genetics, ICTs, Internet, protection of intellectual property rights, synthetic biology are presented as a laboratory bench of scientific and AMEDEO SANTOSUOSSO, OLIVER R. GOODENOUGH technological innovation which calls for legal innovation.