THE CHALLENGE of INNOVATION in LAW the CHALLENGE Do Occur, in Doctrine, in Procedure, in Jurisprudential Understanding, and in Legal Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification of Computer Software for Legal Protection: International Perspectivest

RAYMOND T. NIMMER* PATRICIA KRAUTHAUS** ARTICLES Classification of Computer Software for Legal Protection: International Perspectivest Computer and software technology are international industries in the full sense of the term. United States and foreign companies compete not only in U.S. markets, but also in the international marketplace. These are new industries created during an era in which all major areas of commerce have obviously international, rather than purely domestic frameworks. The technology industries are viewed as central to national economic development in many countries. However, the technology and products are internationally mobile. They entail an information base that can be recreated in many countries, and is not closely confined by local resources. International protection in this context is highly dependent on reciprocal and coordinated legal constraints. The computer industry deals in new and unique products that have no clear antecedents. Defining the character of international legal protection entails not merely defining a framework for protection of particular products, but also developing frameworks of international technology transfer, information flow, and the like. International patterns of legal protection and classification of computer software serve as a case study of legal policy adaptations to new technologies; undoubtedly, in this era of high technology many more such adaptations will be necessary. In this article, we review the developing patterns of international legal protection for software. This review documents a marked differentiation of technology protection themes. In technologically advanced countries, *Professor of Law, University of Houston, Houston, Texas. **Attorney at Law, Houston, Texas. tThe Editorial Reviewer for this article is Larry D. Johnson. 734 THE INTERNATIONAL LAWYER national decisions about software protection reflect an emerging consen- sus that supports copyright as the primary form of product and technology protection. -

Copyleft, -Right and the Case Law on Apis on Both Sides of the Atlantic 5

Less may be more: copyleft, -right and the case law on APIs on both sides of the Atlantic 5 Less may be more: copyleft, -right and the case law on APIs on both sides of the Atlantic Walter H. van Holst Senior IT-legal consultant at Mitopics, The Netherlands (with thanks to the whole of the FTF-legal mailinglist for contributing information and cases that were essential for this article) DOI: 10.5033/ifosslr.v5i1.72 Abstract Like any relatively young area of law, copyright on software is surrounded by some legal uncertainty. Even more so in the context of copyleft open source licenses, since these licenses in some respects aim for goals that are the opposite of 'regular' software copyright law. This article provides an analysis of the reciprocal effect of the GPL- family of copyleft software licenses (the GPL, LGPL and the AGPL) from a mostly copyright perspective as well as an analysis of the extent to which the SAS/WPL case affects this family of copyleft software licenses. In this article the extent to which the GPL and AGPL reciprocity clauses have a wider effect than those of the LGPL is questioned, while both the SAS/WPL jurisprudence and the Oracle vs Google case seem to affirm the LGPL's “dynamic linking” criterium. The net result is that the GPL may not be able to be more copyleft than the LGPL. Keywords Law; information technology; Free and Open Source Software; case law; copyleft, copyright; reciprocity effect; exhaustion; derivation; compilation International Free and Open Source Software Law Review Vol. -

Fall 2021 Schedule of Classes, Rev 5/24/21

Find the most UPDATED LIST OF CLASSES in the online searchable schedule at WLAC.edu 2021 Fall Classes You’re invited to attend Information Sessions about our programs of study…see calendar FALL 2021 CLASSES: GETTING STARTED Online Searchable Schedule How to Get Started: Video Instructions | Written Instructions | Enrollment Workshop Sign Up Other Admissions Information Questions? Email: [email protected] Call: (424) 371-7734 Live Chat Dates to Know Free College Session Period Aug 30 – Dec 19 • Through the College & Career Division, you can 8-Week Sessions: Aug 30 – Oct 24 take free classes that prepare you to succeed in Oct 25 – Dec 19 math, English and other classes (BSICSKL, VOC ED) • Prepare for the GED or improve your English (ESL) • Priority Enrollment Begins ................. May 24 • Earn college credit for your job or internship • Open Enrollment Begins ................... June 18 • Complete job programs that take less than 1 year • How to find your registration date and get job success skills • FINAL EXAMS SCHEDULE................. PAGE 4 Page 1 - rev 5/27/21 WLAC $0 Tuition Promise Program Orientation Workshops West’s LA College Promise (LACP) program provides FREE TUITION to first-time freshmen of any age and income that commit to full-time enrollment. Participants also earn priority registration and support vouchers for transportation, books, or dining at the Wildcat Café. Are you ready to join LACP? Attend this orientation session to: Learn about the LA College Promise program requirements Explore learning and career pathways Review wrap-around services, student support programs, the career connections center, and more! Register at BIT.LY/WLAC-LACP Follow us on Instagram @wlacoutreach or visit bit.ly/wlac-freshmen for more information. -

Pirating in Lacuna

Beijing Law Review, 2019, 10, 829-838 http://www.scirp.org/journal/blr ISSN Online: 2159-4635 ISSN Print: 2159-4627 Pirating in Lacuna D. S. Madhumitha B.com LLB (Hons), Tamil Nadu National Law University, Tiruchirapalli., India How to cite this paper: Madhumitha, D. S. Abstract (2019). Pirating in Lacuna. Beijing Law Review, 10, 829-838. With development of industries and a welcome to the era of globalization https://doi.org/10.4236/blr.2019.104045 along with information technology, many software companies came into be- ing. Tech and tech experts made it easier to pirate the software of the pro- Received: May 31, 2019 Accepted: August 17, 2019 ducers. Problems to the customer as well as to the content owner are present. Published: August 20, 2019 One of major lacunas is the Judiciary being indecisive with the adamant growth of digital world as to the punishment and the reduction of crime, no Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and separate laws by the legislators to protect the software piracy as a distinct Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative crime. Lack of enforcement mechanism by the executive and administrative Commons Attribution International bodies leads to the increase of piracy in software. License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Keywords Open Access Software, Law, Piracy, Judiciary, Punishment 1. Introduction Software piracy is a theft by both direct and indirect means such as use of soft- ware, copying or distribution of software by illegal means. It is such profitable business that causes heavy losses for the publishers of the software, the result is the inflation in price for the consumer. -

Downloads.” International Review of Law, Computers and Technology, 15, No

Nova Southeastern University From the SelectedWorks of Pearl Goldman 2008 Legal Education and Technology II: An Annotated Bibliography Pearl Goldman Available at: https://works.bepress.com/pearl_goldman/10/ Legal Education and Technology II: An Annotated Bibliography* Pearl Goldman** The digital revolution in legal education has engendered a large body of scholarship. To help legal educators locate materials that inform and enrich their teaching and writing, Professor Goldman offers an updated annotated bibliography of articles, commentaries, conference papers, essays, books, and book chapters that examine the impact of technology on legal education. Introduction. .416 Acronyms. 417 Bibliography. 418 Specific Technologies. .418 Communications Technology. 418 Information Technology . 419 Instructional Technology. 423 Artificial Intelligence. 423 Electronic Course Materials. .427 Film and Television. 436 Presentation Technology. 438 Simulations and Games. 440 Tutorials (CAI or CAL). 442 Miscellaneous Instructional Technologies. 444 Curriculum. 446 Clinical Legal Education. 446 Doctrinal Courses. 447 Skills Courses and Programs. 453 Distance Education and Distance Learning. .466 Pedagogy . 476 Law Schools. .482 Administrative Considerations. .482 Law Faculty. 483 Law Libraries and Librarians. 487 * © Pearl Goldman, 2008 ** Professor of Law, Nova Southeastern University Shepard Broad Law Center, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The author expresses gratitude to Maxine Scheffler for her interlibrary loan efforts, to Mary Paige Smith and Carol Yecies -

Documents on Display

Annual Report 2011 on Form 20-F Annual Report 2011 on Form 20-F As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 12, 2012 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) or 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Or Í ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2011 Or ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Or ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 1-3334 REED ELSEVIER PLC REED ELSEVIER NV (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) England The Netherlands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) 1-3 Strand, London, WC2N 5JR, England Radarweg 29, 1043 NX, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (Address of principal executive offices) (Address of principal executive offices) Henry Udow Jans van der Woude Company Secretary Company Secretary Reed Elsevier PLC Reed Elsevier NV 1-3 Strand, London, WC2N 5JR, England Radarweg 29, 1043 NX, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 011 44 20 7930 7077 011 31 20 485 2222 [email protected] [email protected] (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address -

Fifty Years of Open Source Movement: an Analysis Through the Prism of Copyright Law

FIFTY YEARS OF OPEN SOURCE MOVEMENT: AN ANALYSIS THROUGH THE PRISM OF COPYRIGHT LAW V.K. Unni* I. INTRODUCTION The evolution of the software industry is a case study in itself. This evolution has multiple phases and one such important phase, termed open source, deals with the manner in which software technology is held, developed, and distributed.1 Over the years, open source software has played a leading role in promoting the Internet infrastructure and thus programs utilizing open source software, such as Linux, Apache, and BIND, are very often used as tools to run various Internet and business applications.2 The origins of open source software can be traced back to 1964–65 when Bell Labs joined hands with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and General Electric (GE) to work on the development of MULTICS for creating a dynamic, modular computer system capable of supporting hundreds of users.3 During the early stages of development, open source software had a very slow beginning primarily because of some preconceived notions surrounding it. Firstly, open source software was perceived as a product of academics and hobbyist programmers.4 Secondly, it was thought to be technically inferior to proprietary software.5 However, with the passage of time, the technical issues got relegated to the backside and issues pertaining to copyright, licensing, warranty, etc., began to be debated across the globe.6 * Professor—Public Policy and Management, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta; Thomas Edison Innovation Fellow (2016–17), Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property, George Mason University School of Law. 1. -

Digital Copyright Law Exploring the Changing Interface Between

Digital Copyright Law Exploring the Changing Interface Between Copyright and Regulation in the Digital Environment Nicholas Friedrich Scharf PhD University of East Anglia UEA Law School July 2013 Word count: 98,020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there-from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis seeks to address and clarify the changing interface between copyright law and other forms of regulation in the digital environment, in the context of recorded music. This is in order to explain the problems that rightsholders have had in tackling the issue of unauthorised copyright infringement facilitated by digital technologies. Copyright law is inextricably bound-up with technological developments, but the ‘convergence’ of content into a single digital form was perceived as problematic by rightsholders and was deemed to warrant increased regulation through law. However, the problem is that the reliance on copyright law in the digital environment ignores the other regulatory influences in operation. The use of copyright law in a ‘preventative’ sense also ignores the fact that other regulatory factors may positively encourage users to behave, and consume in ways that may not be directly governed by copyright. The issues digital technologies have posed for rightsholders in the music industry are not addressed, or even potentially addressable directly through law, because the regulatory picture is complex. The work of Lawrence Lessig, in relation to his regulatory ‘modalities’ can be applied in this context in order to identify and understand the other forms of regulation that exist in the digital environment, and which govern user behaviour and consumption. -

Is the License Still the Product? Robert W

University of Washington School of Law UW Law Digital Commons Articles Faculty Publications 2018 Is the License Still the Product? Robert W. Gomulkiewicz University of Washington School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/faculty-articles Part of the Computer Law Commons, and the Contracts Commons Recommended Citation Robert W. Gomulkiewicz, Is the License Still the Product?, 60 Ariz. L. Rev. 425 (2018), https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/faculty- articles/312 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IS THE LICENSE STILL THE PRODUCT? Robert W. Gomulkiewicz* The Supreme Court rejected the use of patent law to enforce conditional sales contracts in Impression Products v. Lexmark. The case appears to be just another step in the Supreme Court’s ongoing campaign to reset the Federal Circuit’s patent law jurisprudence. However, the decision casts a shadow on cases from all federal circuits that have enforced software licenses for more than 20 years and potentially imperils the business models on which software developers rely to create innovative products and to bring those products to market in a variety of useful ways. For over two decades, we could say that the license is the product— software provides the functionality but the license provides what can be done with the software. Impression Products now raises a critical question for the software industry: is the license still the product? This Article answers that question by assessing the impact of the Impression Products case on software licensing. -

Open Source Software, Access to Knowledge and Software Licensing

100 • XXVI World Congress of Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy Open source software, access to knowledge and software licensing Marcella Furtado de Magalhães Gomes1 Roberto Vasconcelos Novaes2 Mariana Guimarães Becker3 Abstract: The world depends more and more on computers. Open source and free software create the ideal conditions to access the fundamental digital tools, allowing the advance of knowledge, research and development in countries such as Brazil that would be otherwise deprived of these kinds of benefits. In spite of the common terms, there are different ways to license and distribute open source software. The open source spectrum ranges from complete grant of commercial uses to those that demand that derivative works are distributed un- der the same license terms. These differences have important economical, legal and technical consequences. Those different structures affect software develop- ment, longevity of projects and software distribution. In USA there is a better developed and structured legal precedent collection. In Brazil, however, the legal sphere is yet to study the precise rules and con- sequences of open source software, especially concerning intellectual property and patents. Nevertheless, in the past decade Brazil government had supported the utiliza- tion of the open source software in its internal organizations. There is also a new legislation that illuminates the uses and advantages of those technologies. In this paper we present this Brazilian legislation regarding open source soft- ware licensing, and also analyses the gains of productivity or economic benefits 1Doutora e Mestre em Filosofia do Direito pela Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Profa. da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Direito – Departamen- to de Direito do Trabalho e Introdução ao Estudo do Direito. -

Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form 20-F

169724 20-F Cover_v2.qxd 7/3/07 16:00 Page 1 > www.reedelsevier.com Reed Elsevier Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form 20-F Annual Report 2006 on Form As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 22, 2007 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) n REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) or 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Or ¥ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2006 Or n TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Or n SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 1-3334 REED ELSEVIER PLC REED ELSEVIER NV (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) England The Netherlands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) 1-3 Strand Radarweg 29 London WC2N 5JR 1043 NX Amsterdam England The Netherlands (Address of principal executive offices) (Address of principal executive offices) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of exchange on which Title of each class registered Reed Elsevier PLC: American Depositary Shares (each representing four Reed Elsevier PLC ordinary shares) New York Stock Exchange Ordinary shares of 12.5p each (the ""Reed Elsevier PLC ordinary shares'') New York Stock Exchange* Reed Elsevier NV: American Depositary Shares (each representing two Reed Elsevier NV ordinary shares) New York Stock Exchange Ordinary shares of 40.06 each (the ""Reed Elsevier NV ordinary shares'') New York Stock Exchange* * Listed, not for trading, but only in connection with the listing of the applicable Registrant's American Depositary Shares issued in respect thereof. -

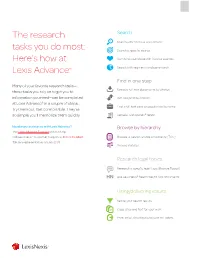

The Research Tasks You Do Most: Here's How at Lexis Advance®

The research Search Search with “terms & connectors” tasks you do most: Search a specific source Here’s how at Combine sources/search favorite sources Lexis Advance® Search with segments and commands Find in one step Many of your favorite research tasks— Retrieve full-text documents by citation those tasks you rely on to get you to information you need—can be completed Get and print by citation at Lexis Advance® in a couple of steps. Find a full-text case or popular law by name Try them out. Get comfortable. They’re so simple you’ll memorize them quickly. Request a Shepard’s® report Need more assistance with Lexis Advance? Browse by hierarchy The Lexis Advance Support site can help. Call LexisNexis® Customer Support at 800-543-6862. Browse or search a table of contents (TOC) Talk to a representative virtually 24/7. Browse statutes Research legal topics Research a specific legal topic (Browse Topics) Use LexisNexis® headnotes to find documents Using/delivering results Refine your search results Copy cites and text for your work Print, email, download and save to Folders Search Search with “terms & connectors” Combine sources/search favorite sources To combine sources: 1. Enter a partial source name in the red search box. The word wheel will make suggestions. Select a source. 2. Repeat to add more sources to your search. The source combination is saved automatically in Recent & Favorites. Just enter your words and connectors in the red search box, e.g., same sex! W/10 marriage, and select Search. Lexis Advance View recent searches and create Favorites: automatically interprets search commands such as ! and * • Select the Filters pull-down menu in the red search box to truncate words and W/n, OR, AND, etc.