Equal Opportunities for Short Term Contract and Freelance Workers in Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

Press Release Potsdam Declaration

Press Release Potsdam 19.10.2018 Potsdam Declaration signed by 21 public broadcasters from Europe “In times such as ours, with increased polarization, populism and fixed positions, public broadcasters have a vital role to play across Europe.” A joint statement, emphasizing the inclusive rather than divisive mission of public broadcasting, will be signed on Friday 19th October 2018 in Potsdam. Cilla Benkö, Director General of Sveriges Radio and President of PRIX EUROPA, and representatives from 20 other European broadcasters are making their appeal: “The time to stand up for media freedom and strong public service media is now. Our countries need good quality journalism and the audiences need strong collective platforms”. The act of signing is taking place just before the Awards Ceremony of this year’s PRIX EUROPA, hosted by rbb in Berlin and Potsdam from 13-19 October under the slogan “Reflecting all voices”. The joint declaration was initiated by the Steering Committee of PRIX EUROPA, which unites the 21 broadcasters. Potsdam Declaration, 19 October 2018 (full wording) by the 21 broadcasters from the PRIX EUROPA Steering Committee: In times such as ours, with increased polarization, populism and fixed positions, public broadcasters have a vital role to play across Europe. It has never been more important to carry on offering audiences a wide variety of voices and opinions and to look at complex processes from different angles. Impartial news and information that everyone can trust, content that reaches all audiences, that offers all views and brings communities together. Equally important: Public broadcasters make the joys of culture and learning available to everyone, regardless of income or background. -

European Public Service Broadcasting Online

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, COMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH CENTRE (CRC) European Public Service Broadcasting Online Services and Regulation JockumHildén,M.Soc.Sci. 30November2013 ThisstudyiscommissionedbytheFinnishBroadcastingCompanyǡYle.Theresearch wascarriedoutfromAugusttoNovember2013. Table of Contents PublicServiceBroadcasters.......................................................................................1 ListofAbbreviations.....................................................................................................3 Foreword..........................................................................................................................4 Executivesummary.......................................................................................................5 ͳIntroduction...............................................................................................................11 ʹPre-evaluationofnewservices.............................................................................15 2.1TheCommission’sexantetest...................................................................................16 2.2Legalbasisofthepublicvaluetest...........................................................................18 2.3Institutionalresponsibility.........................................................................................24 2.4Themarketimpactassessment.................................................................................31 2.5Thequestionofnewservices.....................................................................................36 -

Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the OSCE

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Other Publications from the Center for Global Center for Global Communication Studies Communication Studies (CGCS) 4-2003 Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the OSCE Tarlach McGonagle Bethany Davis Noll Monroe Price University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cgcs_publications Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation McGonagle, Tarlach; Davis Noll, Bethany; and Price, Monroe. (2003). Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the OSCE. Other Publications from the Center for Global Communication Studies. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgcs_publications/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgcs_publications/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the OSCE Abstract There are a large number of language-related regulations (both prescriptive and proscriptive) that affect the shape of the broadcasting media and therefore have an impact on the life of persons belonging to minorities. Of course, language has been and remains an important instrument in State-building and maintenance. In this context, requirements have also been put in place to accommodate national minorities. In some settings, there is legislation to assure availability of programming in minority languages.1 Language rules have also been manipulated for restrictive, sometimes punitive ends. A language can become or be made a focus of loyalty for a minority community that thinks itself suppressed, persecuted, or subjected to discrimination. Regulations relating to broadcasting may make language a target for attack or suppression if the authorities associate it with what they consider a disaffected or secessionist group or even just a culturally inferior one. -

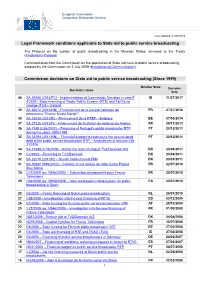

List of Public Broadcasting Decisions

European Commission Competition Directorate-General Last updated: 01/07/2019 Legal Framework conditions applicable to State aid to public service broadcasting The Protocol on the system of public broadcasting in the Member States, annexed to the Treaty (Amsterdam Protocol). Communication from the Commission on the application of State aid rules to public service broadcasting, adopted by the Commission on 2 July 2009 (Broadcasting Communication). Commission decisions on State aid to public service broadcasting (Since 1999) Member State Decision Decision name date 40 SA.39346 (2014/FC) - Implementation of Commission Decision in case E IE 11/07/2017 4/2005 - State financing of Radio Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) and Teilifís na Gaeilge (TG4) - Ireland 39 SA.36672 (2013/NN) - Financement de la société nationale de FR 27/07/2016 programme "France Media Monde" 38 SA.32635 (2012/E) – Financement de la RTBF – Belgique BE 07/05/2014 37 SA.37136 (2013/N) - Financement de la station de radio locale France FR 08/11/2013 36 SA.7149 (C85/2001) – Financing of Portugal's public broadcaster RTP PT 20/12/2011 during the years 1992-1998 35 SA.33294 (2011/NN) – Financial support to restructure the accumulated PT 20/12/2011 debt of the public service broadcaster RTP – Amendment of decision NN 31/2006 34 SA.27688 (C19/2009) - Aid for the restructuring of TV2/Danmark A/S DK 20/04/2011 33 C2/2003 – Financing of TV2/Danmark DK 20/04/2011 32 SA.32019 (2010/N) – Danish radio channel FM4 DK 23/03/2011 31 SA.30587 (N95/2010) – Création d’une station de radio locale France FR 22/07/2010 Bleu Maine 30 C27/2009 (ex. -

Eurodoc Executive Meeting – an Exclusive Meeting Platform for Documentary Executives and Commissioning Editors

EURODOC EXECUTIVE MEETING – AN EXCLUSIVE MEETING PLATFORM FOR DOCUMENTARY EXECUTIVES AND COMMISSIONING EDITORS Tuesday, 2nd of October 2018 Geneva, Eurodoc for Executives CHANGE IN PUBLIC SERVICE PLATFORM CURATING – MORE THAN ALGORHYTHM ? With Jeroen Depraetere, Head of Television and Future, EBU Curation and algorithms as ways of enhancing our service are definitely something public service should take up (have taken up…), but it seems to be developing very slowly almost everywhere. The news of the planned "Alliance" of France Televisions, ZDF and RAI, or the planned joint streaming service of BBC, Channel4 and ITV make it very clear that also the European public service media have understood that the media landscape will be dominated by big international or global players. The survival for documentary programs and smaller players in this landscape will require co-operation and high quality of not only the content but also the service. We may find ourselves having to create and defend a position not within one national public service broadcaster but a conglomerate of many. LUNCH for Executives only 2.30 PM – 5 PM WELCOME & INTRODUCTION INPUT by Jeroen Depraetere, Head of Television and Future, European Broadcasting Union EBU, Geneva, introducing to the « Alliance » of France Télévision, ZDF and RAI and other public initiatives followed by a discussion INTERNATIONAL CASE STUDYS by our participants from the different services such as ARTE, SRF, HBO etc. THE EURODOC EXECUTIVE’S MEETING Since 2013, Eurodoc also offers an exclusive opportunity to meet amongst Documentary Executives and Commissioning Editors only. This exclusive meeting always takes place on the first day of the Eurodoc session and is curated by Anita Hugi (SRF) for Eurodoc. -

Mediawan Enters Into Exclusive Talks with on Kids & Family, the European Leader in Animation, with a View to Acquiring a Majority Stake

MEDIAWAN ENTERS INTO EXCLUSIVE TALKS WITH ON KIDS & FAMILY, THE EUROPEAN LEADER IN ANIMATION, WITH A VIEW TO ACQUIRING A MAJORITY STAKE • Mediawan and ON kids & family announce having entered into exclusive talks with a view to the former acquiring a 51% to 55% majority stake in the latter • A strategic operation for Mediawan, which will join forces with the European leader in the production of animated content with internationally reckoned global franchises like The Little Prince, Playmobil, Iron Man, Chaplin and, most recently, Miraculous Ladybug • The ON kids & family group’s co-founders, Aton Soumache and Dimitri Rassam, and the main shareholders, including Thierry Pasquet, will team up with Mediawan. Aton Soumache will also continue to manage the Group as ON kids & family’s CEO • Mediawan’s investment will be partly achieved through a capital increase allowing ON kids & family to accelerate its growth and its international positioning as a leading player in animation in Europe with worldwide recognition • ON kids & family produces major international audiovisual creations by developing emblematic brands with considerable commercial potential, and will continue to develop high-end content via the creation of powerful franchises and the management of world-renowned intellectual property Paris, December 17, 2017, 8 pm (CET) - Mediawan (Ticker: MWD – ISIN: FR0013247137), an independent European audiovisual content platform, is continuing its development by entering into exclusive talks with the shareholders of ON kids & family, a major European player in the production of animated content for children, with a view to acquiring a majority stake. Backed by a joint project and a shared vision of the Entertainment sector, Mediawan and ON kids & family want, via this strategic operation, to establish a very strong presence on the European and international markets. -

Public Broadcaster Comparison 2016

Analysis of Government Support for Public Broadcasting Nordicity Prepared for CBC|Radio-Canada April 11, 2016 About Nordicity Nordicity (www.nordicity.com) is a powerful analytical engine with expertise in strategy and business, evaluation and economics, policy and regulation for the arts, cultural and creative industries. Because of Nordicity’s international presence, it has become widely recognized for its ability to translate developments and best practices between markets for the private, public and third sectors. Nordicity would like to Dr. Manfred Kops of the Institute for Broadcasting Economics at the University of Cologne for his contribution to the research and analysis of public broadcasting funding in Germany. Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 4 2. The Potential Benefits of Public Broadcasting 5 2.1 Market failure in broadcasting 5 2.2 Role of public broadcasting 5 2.3 Potential benefits index 6 3. International Comparison of Public Broadcasting 9 3.1 Public funding for public broadcasting 9 3.2 Public funding vs. potential benefits 11 3.3 Commercial revenues 12 3.4 Advertising revenues 15 3.5 Public funding by type of funding tenure 18 4. The Canadian Government’s Economic Support for Culture 19 5. Funding Models for Public Broadcasting 22 5.1 Overview of funding models 22 5.2 Funding model changes in selected countries 24 5.2.1 France 24 5.2.2 Spain 28 5.2.3 Germany 30 5.2.4 Finland 34 5.2.5 United Kingdom 35 5.3 Key findings 38 References and Data Sources 40 Appendix A: Statistics for Public Broadcasters -

2020 Selection

APOLLO 11: BACK ON THE MOON CODED BIAS KILLING PATIENT ZERO PICTURE A SCIENTIST APOLLO 11 : RETOUR SUR LA LUNE Written and directed by Shalini Kantayya Written and directed by Laurie Lynd Written and directed by Ian Cheney and Sharon Shattuck Directed by Charles-Antoine de Rouvre 85 min - US - 2020 100 min - Canada - 2019 Written by Sophie Bocquillon and Charles-Antoine de © 7th Empire Media © Fadoo Productions 97 min - US - 2020 Rouvre French Premiere In association with Fine Point Films © Uprising LLC In association with The Wonder Collaborative 96 min - France - 2019 French Premiere French Premiere © Grand Angle Productions - Groupe EDM Modern society sits at the intersection of two In association with Mediawan Thematics, Sveriges Scapegoated as “Patient Zero” at the center of Television, Al Arabya Channel, RSI, HRT Croatia, crucial questions: what does it mean when Picture A Scientist chronicles the groundswell TVP Poland, RTVS, SRF, Czech Television and artificial intelligence increasingly governs our the AIDS epidemic, Gaëtan Dugas was the France Télévisions liberties? And what are the consequences for handsome, openly gay French-Canadian flight of researchers who are writing a new chapter French broadcast: France 2, Toute l'Histoire the people AI is biased against? When MIT attendant characterized as singlehandedly for women scientists. Biologist Nancy Hopkins, Media Lab researcher Joy Buolamwini spreading AIDS to North America. In this chemist Raychelle Burks, and geologist Jane Willenbring lead viewers on a journey deep 16 July 1969. A rocket, carrying Apollo 11, sits discovers that most facial-recognition software riveting documentary, director Laurie Lynd sets into their own experiences in the sciences, on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral awaiting does not accurately identify darker-skinned out to dismantle this myth. -

Belgian Audiovisual Technologies

BELGIAN AUDIOVISUAL TECHNOLOGIES Chief editor: Fabienne L’Hoost Authors: Wouter Decoster, Sammy Sioen & Christelle Charlier Graphic design and layout: Bold&pepper COPYRIGHT © Reproduction of the text is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Date of publication: March 2018 Printed on FSC-labelled paper This publication is also available to be consulted at the website of the Belgian Foreign Trade Agency: www.abh-ace.be BELGIAN AUDIOVISUAL TECHNOLOGIES TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR 4-19 INTRODUCTION 6 SECTION 1 : EVENT TECHNOLOGIES 7 SECTION 2 : BROADCASTING TECHNOLOGIES 9 SECTION 3 : IMMERSIVE & INTERACTIVE TECHNOLOGIES 12 SECTION 4 : STAKEHOLDERS 15 CHAPTER 2 SUCCESS STORIES IN BELGIUM 20-39 CATEGORY EVENT TECHNOLOGIES AVOLON 22 BARCO 24 FREECASTER 26 CATEGORY BROADCASTING TECHNOLOGIES EVS 28 MEDIAGENIX 30 SOFTRON 32 CATEGORY IMMERSIVE & INTERACTIVE TECHNOLOGIES I-ILLUSIONS 34 DREAMWALL / KEYWALL 36 NOZON 38 CHAPTER 3 DIRECTORY OF COMPANIES 40-49 3 PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR present in Belgium such as the European Institutions. This INTRODUCTION made them highly competitive on a global scale. The more broadcasting technologies enter the sphere of specialized ICT, the more Belgian companies grow as glob al leaders. In the Global Competitiveness Index 20172018, Belgium came in 12th place on the availability of latest technologies and 10th on fixedbroadband Internet sub scriptions. As a result, Belgium started the digitalization of television with a head start, and quickly made the switch to content on alternative devices such as tablets and smart Behind every movie that made you laugh, every event that phones. At the crossroads between event technology and made you cheer and every step in interactive and immer broadcasting technology is the specialization of live broad sive media that left you amazed, the key driver was technol casting. -

The Value of Public Service Media

The Value of Public Service Media T he worth of public service media is under increasing scrutiny in the 21st century as governments consider whether the institution is a good investment and a fair player in media markets. Mandated to provide universally accessible services and to cater for groups that are not commercially attractive, the institution often con- fronts conflicting demands. It must evidence its economic value, a concept defined by commercial logic, while delivering social value in fulfilling its largely not-for-profit public service mission and functions. Dual expectations create significant complex- The Value of ity for measuring PSM’s overall ‘public value’, a controversial policy concept that provided the theme for the RIPE@2012 conference, which took place in Sydney, Australia. This book, the sixth in the series of RIPE Readers on PSM published by NORDI- Public Service Media COM, is the culmination of robust discourse during that event and the distillation of its scholarly outcomes. Chapters are based on top tier contributions that have been revised, expanded and subject to peer review (double-blind). The collection investi- gates diverse conceptions of public service value in media, keyed to distinctions in Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Fiona Martin (eds.) the values and ideals that legitimate the public service enterprise in media in many countries. Fiona Martin (eds.) Gregory Ferrell Lowe & RIPE 2013 University of Gothenburg Box 713, SE 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Telephone +46 31 786 00 00 (op.) Fax +46 31 786 46 55 E-mail: -

As of August 27Th COUNTRY COMPANY JOB TITLE

As of August 27th COUNTRY COMPANY JOB TITLE AFGHANISTAN MOBY GROUP Director, channels/acquisitions ALBANIA TVKLAN SH.A Head of Programming & Acq. AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION Acquisitions manager AUSTRALIA FOXTEL Acquisitions executive AUSTRALIA SBS Head of Network Programming AUSTRALIA SBS Channel Manager Main Channel AUSTRALIA SBS Head of Unscripted AUSTRALIA SBS Australia Channel Manager, SBS Food AUSTRALIA SBS Television International Content Consultant AUSTRALIA Special Broadcast Service Director TV and Online Content AUSTRALIA SPECIAL BROADCASTING SERVICE CORPORATION Acquisitions manager (unscripted) AUSTRIA A1 TELEKOM AUSTRIA AG Head of Broadcast & SAT AUSTRIA A1 TELEKOM AUSTRIA AG Broadcast & SAT AZERBAIJAN PUBLIC TELEVISION & RADIO BROADCASTING AZERBAIJAN Director general COMPANY AZERBAIJAN PUBLIC TELEVISION & RADIO BROADCASTING AZERBAIJAN Head of IR COMPANY AZERBAIJAN PUBLIC TELEVISION & RADIO BROADCASTING AZERBAIJAN Deputy DG COMPANY AZERBAIJAN GAMETV.AZ PRODUCER CENTRE General director BELARUS MEDIA CONTACT Buyer BELARUS MEDIA CONTACT Ceo BELGIUM NOA PRODUCTIONS Ceo ‐ producer BELGIUM PANENKA NV Managing partner RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE COMMUNAUTE BELGIUM Head of Acquisition Documentary FRANCAISE RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE COMMUNAUTE BELGIUM Responsable Achats Programmes de Flux FRANCAISE RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE COMMUNAUTE BELGIUM Buyer FRANCAISE RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE COMMUNAUTE BELGIUM Head of Documentary Department FRANCAISE RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE COMMUNAUTE BELGIUM Content acquisition