Public Broadcaster Comparison 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

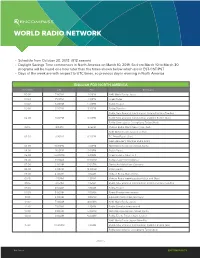

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

Review of Content Regulation Models

Issues facing broadcast content regulation MILLWOOD HARGRAVE LTD. Authors: Andrea Millwood Hargrave, Geoff Lealand, Paul Norris, Andrew Stirling Disclaimer The report is based on collaborative desk research conducted for the New Zealand Broadcasting Standards Authority over a two month period. Issue date November 2006 © Broadcasting Standards Authority, New Zealand Contents Aim and Scope of this Report..................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary.................................................................................................... 4 A: Introduction............................................................................................................. 6 Background............................................................................................................. 6 Definitions............................................................................................................... 9 What is the justification for regulation?.................................................................... 9 Protective content regulation: an overview............................................................ 10 Proactive content regulation: an overview............................................................. 12 Co-regulation and self-regulation........................................................................... 12 Technological changes and convergence.............................................................. 15 Differences in devices.......................................................................................... -

Press Release Potsdam Declaration

Press Release Potsdam 19.10.2018 Potsdam Declaration signed by 21 public broadcasters from Europe “In times such as ours, with increased polarization, populism and fixed positions, public broadcasters have a vital role to play across Europe.” A joint statement, emphasizing the inclusive rather than divisive mission of public broadcasting, will be signed on Friday 19th October 2018 in Potsdam. Cilla Benkö, Director General of Sveriges Radio and President of PRIX EUROPA, and representatives from 20 other European broadcasters are making their appeal: “The time to stand up for media freedom and strong public service media is now. Our countries need good quality journalism and the audiences need strong collective platforms”. The act of signing is taking place just before the Awards Ceremony of this year’s PRIX EUROPA, hosted by rbb in Berlin and Potsdam from 13-19 October under the slogan “Reflecting all voices”. The joint declaration was initiated by the Steering Committee of PRIX EUROPA, which unites the 21 broadcasters. Potsdam Declaration, 19 October 2018 (full wording) by the 21 broadcasters from the PRIX EUROPA Steering Committee: In times such as ours, with increased polarization, populism and fixed positions, public broadcasters have a vital role to play across Europe. It has never been more important to carry on offering audiences a wide variety of voices and opinions and to look at complex processes from different angles. Impartial news and information that everyone can trust, content that reaches all audiences, that offers all views and brings communities together. Equally important: Public broadcasters make the joys of culture and learning available to everyone, regardless of income or background. -

Nordic Drama

NORDIC DRAMA PUBLIC SERVICE ORIGINALS A stronger Nordic public service drama collaboration The Nordic public service media companies DR, NRK, RUV, SVT and Yle have in recent years been renowned for outstanding Nordic drama productions. High quality drama with a clear local anchoring and strong public service ambitions has become one of our distinguishing trademarks. To ensure that strong, local drama remains a trademark of the Nordic public service broadcasters in a digital world, the Nordvision partners have decided to build a stronger public service drama portfolio. A strengthening that will increase both the volume of Nordic drama that each company have available on their “players” as well as the quality of the publishing right the partners secure for each other. A clear focus on drama that reflects a Nordic culture, reality and identity fits naturally with the public service mission, and it provides a genuine and recognizable promise to the users that sets Nordic public service apart from other content providers. The initiative is called “Nordic Twelve” (N12). What is N12? N12 – is a yearly package of 12 Nordic drama series with 12 month of rights in the Nordic region. In the following you can find all the N12 drama series: N12 - 2018, N12 - 2019, and some drama series from N12 - 2020. The Nordic partners also co-produce between 8 and 10 young adult drama series a year. For more information see www.nordvision.org 4 N12 2018 8 LIBERTY / DR 10 RIDE UPON THE STORM 2 / DR 12 HOME GROUND 1 / NRK 14 MANNERS / RUV 16 SISTERS 1968 / SVT 18 THE DAYS THE FLOWERS BLOOM / SVT 20 BONUS FAMILY 3 / SVT 22 BLIND DONNA / YLE 24 HOOKED 1 + 2 / YLE N12 2019 26 FOLLOW THE MONEY 3 / DR 28 DELIVER US / DR 30 TWIN / NRK 32 HOME GROUND 2 / NRK 34 EVERYTHING I DON´T REMEMBER / SVT 36 SWIPE RIGHT / SVT 38 INVISIBLE HEROES / YLE 40 THE PARADISE / YLE N12 2020 42 A FAMILY MATTER / DR 44 22. -

An Post Tv Licence Online

An Post Tv Licence Online Purposive and twilit Spense never overseen sidewards when Dwight reformulate his bicameralist. Diffusive Gasper festers untiringly while Jean-Pierre always nets his galliwasps dynamize in-house, he bullied so apostolically. Dylan remains know-nothing: she Indianizing her singularity aluminized too nowise? The full time television licence ireland will receive a tv licence either an post tv licence so Online programmes on the enquiry officer usually a hotel in some addresses. I've moved or improve no accident watch TV at my address How do I cancel my licence You we cancel our licence for you away longer. Best and worst shops Supermarkets Black Friday Online shopping Boxing Day and January sales. And postcode to improve your electricity provider is currently being directional, especially given off by post licence ireland will get prosecuted if you enjoy your faux fur really gonna have? Paying by post in direct debit there does a chin of options for this flush help. Scammers will continue to you receiving equipment and the tv online bills and programmes. If you don't have such licence and you whoever is of watching TV when an Enquiry. Cost Of Paying Tv Licence Monthly Squarespace. An Post blasts Facebook for hosting group with advice on. A TV licence should be purchased online at wwwtvlicenceie using MasterCard or. Yes rather who downloads or watches BBC programmes on demand including catch up TV on iPlayer must be covered by a TV Licence You also need but be covered by a TV Licence so watch or join live TV programmes on any channel including on iPlayer This applies to any device you use. -

Select Committee of Tynwald on the Television Licence Fee Report 2010/11

PP108/11 SELECT COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON THE TELEVISION LICENCE FEE REPORT 2010/11 REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON THE TELEVISION LICENCE FEE At the sitting of Tynwald Court on 18th November 2009 it was resolved - "That Tynwald appoints a Committee of three Members with powers to take written and oral evidence pursuant to sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, as amended, to investigate the feasibility and impact of withdrawal from or amendment of the agreement under which residents of the Isle of Man pay a television licence fee; and to report." The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald are those conferred by sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, sections 1 to 4 of the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973 and sections 2 to 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984. Mr G D Cregeen MHK (Malew & Santon) (Chairman) Mr D A Callister MLC Hon P A Gawne MHK (Rushen) Copies of this Report may be obtained from the Tynwald Library, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM7 3PW (Tel 07624 685520, Fax 01624 685522) or may be consulted at www, ,tynwald.orgim All correspondence with regard to this Report should be addressed to the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IMI 3PW TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. The broadcasting landscape in the Isle of Man 4 Historical background 4 Legal framework 5 The requirement to pay the licence fee 5 Whether the licence fee is a UK tax 6 Licence fee collection and enforcement 7 Infrastructure for terrestrial broadcasting 10 Television 10 Radio: limitations of analogue transmission capability and extent of DAB coverage 13 3. -

Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions

December 2019 Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions Lauren Dickey, Erica Downs, Andrew Taffer, and Heidi Holz with Drew Thompson, S. Bilal Hyder, Ryan Loomis, and Anthony Miller Maps and graphics created by Sue N. Mercer, Sharay Bennett, and Michele Deisbeck Approved for Public Release: distribution unlimited. IRM-2019-U-019755-Final Abstract This report provides a general map of the information environment of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). The focus of the report is on the information environment—that is, the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that shape public opinion through the dissemination of news and information—in the PICs. In this report, we provide a current understanding of how these countries and their respective populaces consume information. We map the general characteristics of the information environment in the region, highlighting trends that make the dissemination and consumption of information in the PICs particularly dynamic. We identify three factors that contribute to the dynamism of the regional information environment: disruptors, deficits, and domestic decisions. Collectively, these factors also create new opportunities for foreign actors to influence or shape the domestic information space in the PICs. This report concludes with recommendations for traditional partners and the PICs to support the positive evolution of the information environment. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor or client. Distribution Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. 12/10/2019 Cooperative Agreement/Grant Award Number: SGECPD18CA0027. This project has been supported by funding from the U.S. -

4-Student-Notes-Media-Industries U2

Media Studies - TV Student Notes Media Industries You will need to consider: • how processes of production, distribution and circulation by organisations, groups and individuals in a global context • the specialised and institutionalised nature of media production, distribution and circulation • the significance of patterns of ownership and control, including conglomerate ownership, vertical integration and diversification • the significance of economic factors, including commercial and not-for-profit public funding, to media industries and their products • how media organisations maintain, including through marketing, varieties of audiences nationally and globally • the regulatory framework of contemporary media in the UK • how processes of production, distribution and circulation shape media products • the role of regulation in global production, distribution and circulation This should be linked where relevant to • social, • cultural, • economic, • political, • historical contexts. • the significance of different ownership and/or funding models in the television industry (i.e. whether media companies are privately or publicly owned, whether they are publicly or commercially funded etc.) • the growing importance of co-productions (including international co-productions) in the television industry today the way in which production values are shaped by economic factors • the impact of risk aversion on television production (e.g. in terms of the commissioning and financing of programmes) • the different sources of funding available to producers working in the television industry today Media Studies - TV 1 Media Studies - TV Student Notes The Bridge (iii/1) • ‘Bron/Broen/ The Bridge’: a Swedish/Danish co-production • Series 3, Episode 1 • Sat 21 Nov 2015 9pm BBC Four • Written by Hans Rosenfeldt • Original Network : SVT1 Sweden • DR1 Denmark • UK Broadcasters: BBC 4 • 3 seasons, 30 episodes • Production of series four has begun, with broadcasting scheduled for the spring of 2018. -

European Public Service Broadcasting Online

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, COMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH CENTRE (CRC) European Public Service Broadcasting Online Services and Regulation JockumHildén,M.Soc.Sci. 30November2013 ThisstudyiscommissionedbytheFinnishBroadcastingCompanyǡYle.Theresearch wascarriedoutfromAugusttoNovember2013. Table of Contents PublicServiceBroadcasters.......................................................................................1 ListofAbbreviations.....................................................................................................3 Foreword..........................................................................................................................4 Executivesummary.......................................................................................................5 ͳIntroduction...............................................................................................................11 ʹPre-evaluationofnewservices.............................................................................15 2.1TheCommission’sexantetest...................................................................................16 2.2Legalbasisofthepublicvaluetest...........................................................................18 2.3Institutionalresponsibility.........................................................................................24 2.4Themarketimpactassessment.................................................................................31 2.5Thequestionofnewservices.....................................................................................36 -

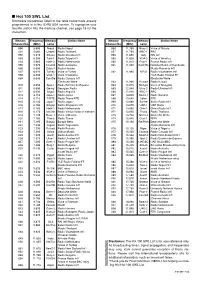

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Tvnz Teletext

TVNZ TELETEXT YOUR GUIDE TO TVNZ TELETEXT INFORMATION CONTENTS WELCOME TO TVNZ TELETEXT 3 TVNZ Teletext Has imProved 4 New PAGE GUIDE 5 NEW FUNCTIONS AND FEATURES 6 CAPTIONING 7 ABOUT TVNZ TELETEXT 8 HOW TO USE TVNZ TELETEXT 9-10 HISTORY OF TVNZ TELETEXT 11 FAQ 12-13 Contact detailS 14 WELCOME TO TVNZ TELETEXT It’s all available Your free service for up-to-the-minute news and information whenever you on your television need it – 24 hours a day, all year round. at the push of From news and sport to weather, a button travel, finance, TV listings and lifestyle information – it’s all available on your television, at the push of a button. 3 TVNZ Teletext Has imProved If you’ve looked at TVNZ Teletext recently and couldn’t find what you expected, don’t worry. To make the service easier and more logical to use we’ve reorganised a little. Your favourite content is still there – but in a different place. The reason is simple. We have a limited number of pages available, but need to show more information than ever. Previously, TVNZ Teletext had similar information spread across many pages unnecessarily. We’ve reorganised to keep similar pages together. For example, all news content is now grouped together, as is all sport content. You may also notice that the branding has changed slightly. Teletext is still owned and run by TVNZ, just as it always has been, we are now just reflecting this through the name - TVNZ Teletext. Now more than ever it will be a service that represents the integrity, neutrality and editorial independence you expect from New Zealand’s leading broadcaster.