Nick Davis Film Discussion Group May 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

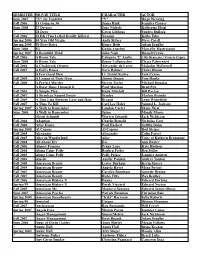

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Alcultura Cinema

Campus de Cádiz / ALCANCES Multicines el Centro: 17:00 horas / 19:30 horas / 22:00 horas Entrada: 4,5€ – Comunidad universitaria UCA: 3´5€ Organizan: Ayuntamiento de Cádiz Vicerrectorado de Responsabilidad Social, Extensión Cultural y Servicios Programación: 29 octubre 5, 12 19 y 26 de noviembre 29 OCTUBRE – MALA SANGRE Título original: Mauvais sang Año: 1986 Duración: 119 min. País: [Francia] Francia Director: Leos Carax Reparto: Denis Lavant, Michel Piccoli, Juliette Binoche, Julie Delpy, Hans Meyer, Hugo Pratt, Serge Reggiani, Carroll Brooks Género: Romance. Drama | Crimen. Neo-noir. Drama romántico. Cine experimental Sinopsis: París, en un futuro cercano. Marc y Hans son dos ladrones que deben dinero a una intransigente mujer americana que les da sólo dos semanas para pagar. Planean robar y vender un nuevo antídoto para curar un virus parecido al del SIDA, que está matando a los que "practican el amor sin amor", pero necesitan un cómplice. Reclutan a Alex, alias "lengua veloz", un chico rebelde que acaba de romper su relación con su novia de 16 años de edad.ítulo original 5 NOVIEMBRE – LA FIESTA DE DESPEDIDA Título original: Mita Tova (The Farewell Party) Año: 2014 Duración: 95 min. País: [Israel] Israel Director: Tal Granit, Sharon Maymon Reparto: Ze'ev Revach, Aliza Rosen, Levana Finkelstein, Raffi Tavor, Ilan Dar, Yosef Carmon, Hilla Sarjon Género: Drama. Comedia | Comedia negra. Vejez. Enfermedad. Comedia dramática Sinopsis: En una residencia de ancianos de Jerusalén, un grupo de amigos construye una máquina para practicar la eutanasia con el fin de ayudar a un amigo enfermo terminal. Pero cuando se extienden los rumores sobre la máquina, otros ancianos les pedirán ayuda, lo que les plantea un dilema emocional y los implica en una aventura disparatada. -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

Printable Oscar Ballot

77th Annual ACADEMY AWARDS www.washingtonpost.com/oscars 2005 NOMINEES CEREMONY: Airs Sunday, February 27, 2005, 8p.m. EST / ABC BEST PICTURE ACTOR ACTRESS “The Aviator” Don Cheadle ("Hotel Rwanda") Annette Bening ("Being Julia") Johnny Depp ("Finding Neverland") Catalina Sandino Moreno ("Maria “Finding Neverland” Full of Grace") “Million Dollar Baby” Leonardo DiCaprio ("The Aviator") Imelda Staunton ("Vera Drake") Clint Eastwood ("Million Dollar Hilary Swank ("Million Dollar “Ray” Baby") Baby") Kate Winslet ("Eternal Sunshine of “Sideways” Jamie Foxx ("Ray") the Spotless Mind") ★ ★ 2004 WINNER: "The Lord of the ★ 2004 WINNER: Sean Penn, "Mystic 2004 WINNER: Charlize Theron, Rings: The Return of the King" River" "Monster" DIRECTOR SUPPORTING ACTOR SUPPORTING ACTRESS Martin Scorsese (”The Aviator”) Alan Alda (”The Aviator”) Cate Blanchett (”The Aviator”) Thomas Haden Church Clint Eastwood (”Million Dollar Laura Linney (”Kinsey”) Baby”) (”Sideways”) Jamie Foxx (”Collateral”) Taylor Hackford (”Ray”) Virginia Madsen (”Sideways”) Morgan Freeman (”Million Dollar Sophie Okonedo (”Hotel Rwanda”) Alexander Payne (”Sideways”) Baby”) Mike Leigh (”Vera Drake”) Clive Owen “Closer”) Natalie Portman (”Closer”) ★ 2004 WINNER: Peter Jackson, "The ★ 2004 WINNER: Tim Robbins, "Mystic ★ 2004 WINNER: Renee Zellweger, Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King" River" "Cold Mountain" ANIMATED FEATURE ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY ADAPTED SCREENPLAY “The Incredibles” “ The Aviator” “Before Sunset” “Shark Tale” “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless “Finding Neverland” Mind” “Shrek 2” “Hotel Rwanda” “Million Dollar Baby” “The Incredibles” “The Motorcycle Diaries” “Vera Drake” “Sideways” ★ 2004 WINNER: "Finding Nemo" ★ 2004 WINNER: "Lost in Translation" ★ 2004 WINNER: "The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King" 1 77th Annual ACADEMY AWARDS www.washingtonpost.com/oscars 2005 NOMINEES CEREMONY: Airs Sunday, February 27, 2005, 8p.m. -

Untitled Warrior Olympics Project, for Neal Moritz and Sony; San Andreas 2, with New Line; and Rampage, Also Through New Line, with Dwayne Johnson Attached to Star

Short Synopsis After a single-mother (Carice van Houten) witnesses terrifying symptoms of demonic possession in her 11-year-old son (David Mazouz), a Vatican representative (Catalina Sandino Moreno) calls on wheelchair-bound scientist Dr. Seth Ember (Aaron Eckhart) to rid him of the evil spirit. Driven by a personal agenda rooted in his own tragic past, Ember enters the boy’s unconscious mind where he confronts a demon as ferocious as it is ingenious. Long Synopsis Eleven-year-old Cameron (David Mazouz) alarms his single mother Lindsay (Carice van Houten) when he begins isolating himself on the floor of his dark room, speaking in ancient languages and displaying other symptoms of demonic possession. Alerted to the situation, Vatican representative Camilla (Catalina Sandino Moreno) recruits wheelchair- bound scientist Dr. Seth Ember (Aaron Eckhart) to extract the evil spirit from the boy. A non-believer who drinks, smokes and prefers to think of his work as “eviction” rather than exorcism, Ember sets up shop with high-tech assistants Riley (Emily Jackson) and Oliver (Keir O’Donnell). Strapped into a life-support system, he enters Cameron’s subconscious mind, where the demon holds the boy captive in an imaginary dream world by appealing to his deepest desire: to be reunited with his estranged father Dan (Matt Nable). Driven by tragic events in his own traumatic past, Ember engages in a fierce battle with the crafty spirit. Ever mindful that the demon, known as “Maggie,” travels from one victim to the next through physical contact, Ember knows that his desperate attempt to save Cameron’s soul could make him the demon’s next host. -

SETDECOR Magazine – Online 2015 Nominations

SETDECOR Magazine – Online 2015 Nominations NOMINATIONS FOR THE 20th ANNUAL CRITICS’ CHOICE MOVIE AWARDS BEST PICTURE BEST YOUNG ACTOR/ACTRESS Birdman Ellar Coltrane – Boyhood Boyhood Ansel Elgort – The Fault in Our Stars Gone Girl Mackenzie Foy – Interstellar The Grand Budapest Hotel Jaeden Lieberher – St. Vincent The Imitation Game Tony Revolori – The Grand Budapest Hotel Nightcrawler Quvenzhane Wallis – Annie Selma Noah Wiseman – The Babadook The Theory of Everything Unbroken BEST ACTING ENSEMBLE Whiplash Birdman Boyhood BEST ACTOR The Grand Budapest Hotel Benedict Cumberbatch – The Imitation The Imitation Game Game Into the Woods Ralph Fiennes – The Grand Budapest Hotel Selma Jake Gyllenhaal – Nightcrawler Michael Keaton – Birdman BEST DIRECTOR David Oyelowo – Selma Wes Anderson – The Grand Budapest Hotel Eddie Redmayne – The Theory of Ava DuVernay – Selma Everything David Fincher – Gone Girl Alejandro G. Inarritu – Birdman BEST ACTRESS Angelina Jolie – Unbroken Jennifer Aniston – Cake Richard Linklater – Boyhood Marion Cotillard – Two Days, One Night Felicity Jones – The Theory of Everything BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY Julianne Moore – Still Alice Birdman – Alejandro G. Inarritu, Nicolas Rosamund Pike – Gone Girl Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris, Jr., Reese Witherspoon – Wild Armando Bo Boyhood – Richard Linklater BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR The Grand Budapest Hotel – Wes Josh Brolin – Inherent Vice Anderson, Hugo Guinness Robert Duvall – The Judge Nightcrawler – Dan Gilroy Ethan Hawke – Boyhood Whiplash – Damien Chazelle Edward Norton – Birdman -

Charles Ramírez Berg Joe M. Dealey, Sr. Professor in Media Studies

Charles Ramírez Berg Joe M. Dealey, Sr. Professor in Media Studies University Distinguished Teaching Professor Board of Regents' Outstanding Teacher Top Ten Great Professor at the University of Texas at Austin Distinguished University Lecturer Department of Radio-Television-Film The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712-1091 (512) 471-4071 (RTF Dept.) (512) 471-4077 (RTF fax) [email protected] http://rtf.utexas.edu/faculty/charles-ramirez-berg __________________________________________________________________ Education 1987 University of Texas at Austin Ph. D. Communication 1975 University of Texas at Austin M.A. Communication 1969 Loyola University, New Orleans, La. B.S. Biological Sciences Teaching Experience 2003- Professor, Department of Radio-Television-Film, UTexas-Austin 1993-2003 Associate Professor, Department of Radio-Television-Film, UTexas-Austin 2007, 1993-96 Graduate Adviser, Department of RTF, UTexas-Austin 1987-1993 Assistant Professor, Department of RTF, UTexas-Austin 1983-1987 Assistant Instructor, Department of RTF, UTexas-Austin 1979-1983 Lecturer, Departments of English, Communication, Linguistics, UTexas-El Paso 1970-1972 Edgewood High School, San Antonio, TX; Biology, Chemistry, Physiology Publications Books The Classical Mexican Cinema: The Poetics of the Exceptional Golden Age Films, University of Texas Press, 2015. Grand Prize Winner, 2016 University Co-Op Robert W. Hamilton Book Awards. Choice Magazine Outstanding Academic Title, American Library Association, 2016. Latino Images in Film: Stereotypes, Subversion, and Resistance. Austin: UTexas Press, 2002. Poster Art from the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema, 1936-1957. U. Guadalajara Press/IMCINE (Mexican Film Institute)/Agrasánchez Film Archive, 1997. Second Ed., 1998. Third Ed. published as Cine Mexicano: Posters from the Golden Age, 1936-1956. -

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

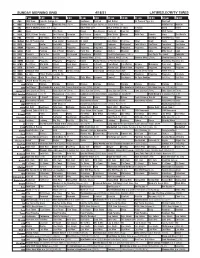

Sunday Morning Grid 4/18/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/18/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News SunPower Dest LA Bull Riding 25 Years of Tiger (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Washington Capitals at Boston Bruins. (N) IndyCar Pre IndyCar 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Relief 7 ABC News This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. QB21 MLS Soccer 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Harvest Gold Coin Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX PROTECT Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue PBA Bowling Super Slam. (N) RaceDay NASCAR Cup Series 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs Paid Prog. Silver Shark News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Relief Dental SmileMO AAA Relief PROTECT Kenmore Bathroom? Paint Like A Can’tHear Transform Sex Abuse 2 2 KWHY Programa Programa Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Nick Lidia Milk Street Cook 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Great Performances (TVG) Å Easy Yoga: The Secret Colorado 3 0 ION Law & Order (TV14) Law & Order (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

"Little Miss Sunshine"

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES In association with Big Beach Present A Dayton/Faris Film A Big Beach/Bona Fide Production GREG KINNEAR TONI COLLETTE STEVE CARELL PAUL DANO with ABIGAIL BRESLIN and ALAN ARKIN Directed by...................................................................JONATHAN DAYTON & .....................................................................................VALERIE FARIS Written by ....................................................................MICHAEL ARNDT Produced by .................................................................ALBERT BERGER & .....................................................................................RON YERXA .....................................................................................MARC TURTLETAUB .....................................................................................DAVID T. FRIENDLY .....................................................................................PETER SARAF Executive Producers.....................................................JEB BRODY .....................................................................................MICHAEL BEUGG Director of Photography ..............................................TIM SUHRSTEDT, A.S.C. Production Design by...................................................KALINA IVANOV Edited by......................................................................PAMELA MARTIN Costumes Designed by.................................................NANCY STEINER Music Composed by ....................................................MYCHAEL -

Découvrez Les Lieux De Tournage Discover Where the fi Lm Was Shot PARCOURS CINÉMA DANS PARIS N°1 PARIS FILM TRAILS

PARCOURS CINÉMA DANS PARIS N°1 PARIS FILM TRAILS Découvrez les lieux de tournage Discover where the fi lm was shot PARCOURS CINÉMA DANS PARIS N°1 PARIS FILM TRAILS Les Parcours Cinéma vous invitent à découvrir Paris, ses quartiers célèbres et insolites à tra- vers des fi lms emblématiques réalisés dans la Capitale. Chaque année, Paris accueille plus de 650 tournages dans 4 000 lieux de décors naturels. Ces Parcours Cinéma sont des guides pour tous les amoureux de Paris et du Cinéma. Follow the Paris Film Trails and explore famous or little-known parts of the city that have featured in classic movies. Over 650 fi lm shoots take place in Paris each year, and some 4,000 different outside locations have been used. The Film Trails are pocket guides for lovers of Paris and the cinema. Mission Cinéma - Mairie de Paris • www.cinema.paris.fr Raconter en cinq minutes l’histoire d’une Tell the story of an amorous encounter rencontre amoureuse dans un quartier de somewhere in Paris – in just fi ve minutes. Paris, tel est le défi qu’ont accepté de relever, avec This was the challenge that twenty fi lm-makers PARIS JE T’AIME, vingt et un réalisateurs venus du from around the world agreed to take up for PARIS monde entier. Ils réinventent notre regard sur Paris JE T’AIME. The result is a sensitive and moving fi lm et nous livrent un fi lm sensible et émouvant... that makes us look at Paris in a new light... Montmartre Bastille Pigalle Écrit et réalisé par Bruno Podalydès Écrit et réalisé par Isabel Coixet Écrit et réalisé par Richard LaGravenese Florence Muller -

A Most Violent Year

A MOST VIOLENT YEAR Yönetmen J.C. Chandor Yapımcılar J.C. Chandor Neal Dodson Anna Gerb Türü Suç, Aksiyon Oyuncular Oscar Isaac Jessica Chastain Albert Brooks Elyes Gabel Catalina Sandıno Moreno Alessandro Nivola David Oyelowo Yapım Yılı 2014 İthalat/Dağıtım Pinema Vizyon Tarihi: 10 Temmuz 2015 SİNOPSİS Akademi ödüllü J. C. Chandor’un yönetmenliğini ve yapımcılığını üstlendiği “A MOST VIOLENT YEAR”, 1981 kışında New York’ta geçen dokunaklı bir suç filmi. 1981, istatistiklere göre şehrin tarihindeki en tehlikeli yılıdır. Abel Morales ( Oscar Isaac); şiddet dolu bu şehirde, Amerikan rüyasının peşinde olan bir Latin Amerikalı göçmendir. Abel, Brooklynli eşi Anna’nın (Jessica Chastain) gangster babasından satın aldığı küçük bir kalorifer yakıtı işini büyütmeye çalışmaktadır. İşini kurallara uygun şekilde yönetmeye kararlıyken, başarıya çıkan merdivenlerin eğri olduğunu fark eder. Bu sırada meydana gelen rekabetler ve nedensiz saldırılar işini, ailesini ve hepsinden önemlisi, yolunun doğruluğuna olan inancını tehdit etmektedir. YAPIM HAKKINDA J.C. Chandor son filmi “A MOST VIOLENT YEAR” ile izleyiciyi bir kez daha tehlikenin ve ahlaki kasvetin eşiğine getiriyor. Film, New York’un kayıtlara göre en şiddetli yılı olan 1981’de beş ilçesinde geçiyor. 1920’lerin yükselen metropolü olan, 1970’lerdeki petrol krizinden çıkan şehir, dramatik bir süreç geçirmiş ve bütçe kesintileri yüzünden duraklama dönemine girmiştir. Bu arada suç oranı ve siyasi yolsuzluklar artmıştır. 80’lerin başı güvenli çevre banliyölere doğru yapılan “Beyaz Göç”ün zirvesiydi. Göçmenler fırsat arayışıyla kasabalara akın ederken şehrin dokusunu ciddi düzeyde değiştiriyorlardı. Gerilim ve karmaşa yüzünden, kapitalizmin merkezinde ticaret yapmak endişeli bir hâl almıştı. Belediye, mafya ve iş dünyası arasındaki kuralların işlediği günler geride kalmıştı. Daha yüksek endüstri ve ticaret düzeyine çıkmaya çalışan küçük iş sahipleri, her ayrıntıdan kendileri sorumlu olacaktı.