The Post-Romantic Era Andrew J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Poetry and Contemporary Reality C. 1870 - 1887

Durham E-Theses French poetry and contemporary reality c. 1870 - 1887 Watson, Lawrence J. How to cite: Watson, Lawrence J. (1976) French poetry and contemporary reality c. 1870 - 1887, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8021/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk FRENCH POETRY AND CONTEMPORARY REALITY c 1870 - 1887 A study of the thematic and stylistic implications of the poetic treatment of the modern and the ephemeral LAWRENCE J WATSON Thesis submitted in the University of Durham for the degree of Doctor of philosophy December 1976 VOLUME TWO FULL COIIMtfTS Oi VULTJlli, TwO P^T TWO ^CMTIlilJiJ) onapter Two: Contemporary Subjects (f) Everyday Lue 478 (g) The World of Sens<?Tion 538 Chapter Three: The Impact of Contemporary Speech 582 (a) 'The Particulcrisation of Poetic Language in the /.ge of Science and ilc^terialism P. -

Germain Nouveau (1851-1920), Un Poète Varois À Redécouvrir

COLLOQUE DU LABORATOIRE BABEL Germain Nouveau (1851-1920), un poète varois à redécouvrir Organisé à l’occasion du centenaire de la mort du poète avec l’aimable autorisation d’Ernest Pignon-Ernest Salle BA. 710 (5 Fév.) 5 et 6 Bâtiment Pi • Campus de Toulon-Porte d’Italie Salle Jules Isaac (6 Fév.) FÉV. 2021 Bibliothèque Méjanes - Allumettes • Aix-en-Provence Contact : Michèle MONTE UFR Lettres, Langues [email protected] et Sciences Humaines GERMAIN NOUVEAU (1851-1920) POURRIÈRES Un vieux clocher coiffé de fer sur la colline. Des fenêtres sans cris, sous des toits sans oiseaux. D’un barbaresque Azur la paix du Ciel s’incline. Soleil dur ! Mort de l’ombre ! Et Silence des Eaux. Marius ! son fantôme à travers les roseaux, Par la plaine ! Un son lent de l’Horloge féline. Quatre enfants sur la place où l’ormeau perd ses os, Autour d’un Pauvre, étrange, avec sa mandoline. Un banc de pierre chaud comme un pain dans le four, Où trois Vieux, dans ce coin de la Gloire du Jour, Sentent au rayon vif cuire leur vieillesse. Babet revient du bois, tenant sa mule en laisse. Noir, le Vicaire au loin voit, d’une ombre au ton bleu, Le Village au soleil fumer vers le Bon Dieu. UN POÈTE VAROIS À REDÉCOUVRIR « Des tonnelles de vigne vierge, des façades aux « fenêtres sans cris », des platanes méditatifs aux vieilles mains de feuilles mortes… Couchée au pied de Sainte-Victoire, Pourrières roussit ou bien blanchoie, transpire ou se les gèle, selon la lumière des saisons. Indifférente aux gloires qui pourraient la guetter. -

Germain Nouveau L'ami De Verlaine Et De Rimbaud

GERMAIN NOUVEAU L'AMI DE VERLAINE ET DE RIMBAUD « Non l’épigone de Rimbaud : son égal. » Louis Aragon Germain Nouveau (1851-1920), peintre et poète ami de Verlaine et de Rimbaud, est mis à l’honneur par la Bibliothèque Méjanes. Une exposition et de nombreux événements lui sont consacrés, du 16 janvier au 17 avril 2021 : l’occasion de s’immerger dans la poésie et les mystères qui entourent une partie de son œuvre... Un parcours de vie singulier : de la bohème parisienne au poète mendiant Né et mort à Pourrières dans le Var, il habite plusieurs années à Commissariat Aix-en-Provence et restera lié à la Provence toute sa vie. Il fait ses Aurélie Bosc, débuts littéraires à Paris, où il fréquente notamment Mallarmé, Conservateur en chef des Verlaine et Rimbaud. bibliothèques, Bibliothèque Interné à Bicêtre après une « crise mystique », il mènera une existence Méjanes, Aix-en-Provence d’ascète et d’errance, tentant de vivre de sa peinture, renonçant à toute ambition littéraire. Comité scientifique Jean-Philippe de Wind Une œuvre poétique à redécouvrir et Pascale Vandegeerde, Admiré par les surréalistes (Breton, Aragon, Eluard), l’œuvre de directeurs de publication des Germain Nouveau a néanmoins sombré dans l’oubli. Pourtant depuis Cahiers Germain Nouveau plus de cinquante ans, des chercheurs démontrent la place importante Eddie Breuil, qu’elle tient dans l’histoire de la poésie française. En effet, on peut docteur ès lettres, auteur de attribuer à Germain Nouveau la paternité d’une partie du recueil des Du Nouveau chez Rimbaud, Paris, Illuminations, traditionnellement attribué à Rimbaud. -

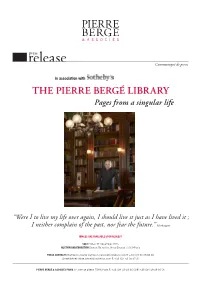

THE PIERRE BERGÉ LIBRARY Pages from a Singular Life

in association with THE PIERRE BERGÉ LIBRARY Pages from a singular life “Were I to live my life over again, I should live it just as I have lived it ; I neither complain of the past, nor fear the future.” Montaigne IMAGES ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST SALE Friday 11 December 2015 AUCTION AND EXHIBITION Drouot Richelieu, 9 rue Drouot 75009 Paris PRESS CONTACTS Sophie Dufresne [email protected] T. +33 (0)1 53 05 53 66 Chloé Brézet [email protected] T. +33 (0)1 53 05 52 32 PIERRE BERGÉ & ASSOCIÉS PARIS 92 avenue d’Iéna 75116 Paris T. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 00 F. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 01 Beginning in DECember 2015, Pierre BergÉ & ASSOCIÉS, in CollAborAtion With SothebY’S, Will be AUCtioning the PERSonAL librARY of Pierre BergÉ. This collection includes 1,600 precious books, manuscripts and musical scores, dating from the 15th to the 20th century. A selection of a hundred of these works will be part of a travelling preview exhibition in Monaco, New York, Hong Kong and London during the summer and autumn of 2015. The first part of the library will be auctioned in Paris on 11 December at the Hôtel Drouot, by Antoine Godeau. This first sale will offer a stunning selection of one hundred and fifty works of literary interest spanning six centuries, from the first edition of St Augustine’s Confessions, printed in Strasbourg circa 1470, to William Burroughs’ Scrap Book 3, published in 1979. The thematic sales which are to follow in 2016 and 2017 will feature not only literary works, the core of the collection, but also books on botany, gardening, music and the exploration of major philosophical and political ideas. -

A History of French Literature from Chanson De Geste to Cinema

A History of French Literature From Chanson de geste to Cinema DAVID COWARD HH A History of French Literature For Olive A History of French Literature From Chanson de geste to Cinema DAVID COWARD © 2002, 2004 by David Coward 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of David Coward to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2002 First published in paperback 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coward, David. A history of French literature / David Coward. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–631–16758–7 (hardback); ISBN 1–4051–1736–2 (paperback) 1. French literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PQ103.C67 2002 840.9—dc21 2001004353 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. 1 Set in 10/13 /2pt Meridian by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com Contents -

Arts 15 Septembre 1967 Par Jacques Vigneault Nous C?

Martr:i.:::~ ~s Arts 15 septembre 1967 LA VIE ET L'OEUVRE DIUN ORPHELIN DE POURRIERES (GERMAIN NOWEAU) par Jacques Vigneault Nous c?nsacrons notre premier chapitre è retracer les principaux événements de la vie du poète. Dans les pages qui suivent, è llaide des poèmes de Germain Nouveau, nous essayons de pénétrer le drame intérieur du poète, d'en suivre le dérou lement et de décrire sa physionomie. Nous essayons ensuite de ~ituer lloeuvre poétique de Germain Nouveau par rapport è celles de Verlaine, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Richepin. Nous analysons plus profondément les influences qu'eurent l'auteur de la Saison en Enfer et celui de Sagesse sur la vie et l'oeuvre de Nouveau. Puis nous décelons les accents surréalistes de son oeuvre. Comme on le sait; la vie de Germain Nouveau s'acheva dans une expérience mystique. Nous faisons remarquer qu'on a trop vite donné un sens métaphysique à son mysticisme et que cette dernière option se présente avant tout comme un refus d'affrontement, une réaction d1échec. Université McGill Montréal SEP 27 1967 LA VIE ET L'OEUVRE D'UN ORPHELIN DE POURRIERES (GERMAIN NOtNEAU) par Jacques Vigneault Thèse de Mattrise ès Arts, préparée sous la direction de Monsieur Henri Jones, Département de langue et littérature françaises, Peterson Hall, le 15 aeptembre 1967. Université McGi11 Montréal 1967 .-:::Cj,coq ... } .. 'j .f ,/ ~ \ @) Jacques Vigneault 1969 \ Mais, je ne suis qu'un fou, je danse, Je tambourine avec mes doigts Sur la vitre de l'existence. Qp'on excuse mon insistance, C'est un fou qu 1 i1 faut que ja sois! Germain Nouveau INTRODUCTION Je ne suis puissant ni riche, Je ne suis rien que le toutou Que le toutou de ma niniche; Je ne suis que le vieux caniche De tous les gens de n'importe où. -

Edouard Jolly À Son Frère Louis 19 13 Novembre : Jules Desdouest Au Recteur De L'académie De Douai 20

SOMMAIRE Avant-propos 7-12 Remerciements 13 Principes de l'établissement du texte 15 1868 Année 1868 17-18 26 mai : Edouard Jolly à son frère Louis 19 13 novembre : Jules Desdouest au recteur de l'Académie de Douai 20 1869 Année 1869 21-22 6 novembre : J. Kremp au recteur de l'Académie de Douai 23 11 novembre : J. Kremp au recteur de l'Académie de Douai 24 26 décembre : La rédaction de La Revue pour tous à Rimbaud 25 1870 Année 1870 27-28 2 janvier : Les Étrennes des orphelins dans La Revue pour tous 29 Premier semestre : Rimbaud à Georges Izambard 30 4 mai : Vitalie Rimbaud à Georges Izambard 31 24 mai : Rimbaud à Théodore de Banville 32-37 13 août : Trois baisers dans la Charge j 38 25 août : Rimbaud à Georges Izambard 39-43 31 août : Rapport du commissaire de police de la Compagnie des Chemins de fer 44 5 septembre : Rimbaud à Georges Izambard 45 24 septembre : Vitalie Rimbaud à Georges Izambard 46 Fin septembre : Lettre de protestation des membres de la Garde nationale de Douai 47 25 septembre : Chronique locale du Libéral du Nord 48 Fin septembre ou fin octobre : Rimbaud à Paul Demeny 49 2 novembre : Rimbaud à Georges Izambard 50 9 novembre : Le Progrès des Ardennes à J. Baudry 51 11 novembre : Scipion Lenel et Léon Deverrière à Georges Izambard 52-53 29 décembre : Le Progrès des Ardennes à MM. Baudry et Dhayle 54 Lettres non retrouvées de 1870 55 1871 Année 1871 57-58 16 avril : Charles Gillet à Georges Izambard 59 17 avril : Rimbaud à Paul Demeny 60-62 13 mai : Rimbaud à Georges Izambard 63-64 Vers le 15 mai : Georges Izambard -

“Translation As Mutation”:Ciaran Carson's in the Light Of

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 14, March 2019-Feb. 2020, pp. 41-50 __________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI “Translation as Mutation”:Ciaran Carson’s In the Light of Elizabeth Delattre University of Lille 3, France Copyright (c) 2019 by Elizabeth Delattre. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Abstract. This article deals with the way Ciaran Carson has managed to translate, or rather “mutate”, some of Arthur Rimbaud’s prose poems Illuminations into an entirely different work, a verse collection in alexandrines, while keeping close to the original spirit. This article will follow three movements, first the form and structure, then the matter of translation proper, and finally the overall tone of the collection which relies on the music of the language itself. Key Words. Rimbaud, Verse, Music, Language, Translating. Resumen. En este artículo se estudia la forma en la que Ciaran Carson ha traducido, o utilizando otra expresión, ha “mutado” algunos de los poemas en prosa de Arthur Rimbaud dando como resultado una colección en versos alejandrinos que mantienen la fidelidad al espíritu original. En este artículo se seguirán tres fases, en primer lugar se estudiará la forma y la estructura de los poemas, después se analizará la traducción propiamente dicha, y finalmente el tono general de la colección, la cual se basa en la propia música del lenguaje. Palabras clave. Rimbaud, versos, música, lenguaje, traducción. ________________________________ ISSN 1699-311X 42 World is crazier and more of it than we think, Incorrigibly plural. -

Germain Nouveau, Poète De L'amour, Vagabond Et Mystiqu

XXE-XXIE SIÈCLES - L'ART, LE SACRÉ GERMAIN NOUVEAU, POÈTE DE L'AMOUR, VAGABOND ET MYSTIQU . LUCIEN SUEL . epuis longtemps, Germain Nouveau est dans mes pensées. D'abord à cause de son œuvre poétique publiée après sa D mort, ces deux livres majeurs que sont la Doctrine de l'amour et les Valentines. Ensuite, en raison des péripéties de sa vie, de son amitié avec Arthur Rimbaud et Paul Verlaine. Germain Nouveau est aussi pour moi une figure du vagabond solitaire, un ancêtre de ces beatniks découverts dans les livres de Jack Kerouac. J'ajoute que Germain Nouveau termina son existence dans l'imitation de Benoît-Joseph Labre, le saint pouilleux qui fréquenta jadis l'église de mon village. Ce qui m'amène à une autre approche, psycho-géographique pourrait-on dire ; sentir ce que lui, homme du Midi, vécut dans cet Artois où j'habite, notam ment avec Verlaine à Arras, la ville de Jean Bodel et Baude Fastoul, les poètes lépreux du Moyen Âge, la ville aussi où naquit Pierre-Jean Jouve. REVUE DES 135 DEUX MONDES XXE-XXIE SIÈCLES -L'ART, LE SACRÉ Germain Nouveau, poète de l'amour, vagabond et mystique Le beffroi d'Arras se redresse Comme la hune au vent d'hiver ; Mais Marseille ! est une bougresse, Qui tempête, au bord de la mer ; Et puis tout naturellement, ce lien, quasiment une commu nion, qui existe entre les poètes à travers le temps, à travers l'espace, un lien qui se matérialise dans les anthologies. J'ai lu pour la première fois le nom de Germain Nouveau dans l'Anthologie de l'humour noir d'André Breton, un livre de poche acheté dans une librairie d'Arras, où j'étais pensionnaire en classe de seconde. -

Marc Alyn L 1 Janvier 2011 — N a C R A

Couv_Phœnix n°1 9/02/11 12:42 Page 1 Au fond, le personnage secret de mon œuvre est Lazare : deux fois né, deux fois mort, ayant traversé l’épaisseur terrifiante des ténèbres pour ressurgir vivant, de l’autre côté. La découverte des ruines de la cité phénicienne de Byblos, au Liban, m’offrira l’occasion d’une telle renaissance. Soudain, là- bas, il fit très jour et j’aperçus, depuis les terrasses dominant la mer, sur le promontoire des siècles réduits en poudre, la vie et la mort faisant l’amour au bord d’une tombe royale d’où émergeait un alphabet miroitant de scarabées : Passeur des mots ton crible est une barque semblable à la barque des morts Et tu vas à travers la grande nuit de l’encre Avec ton cœur qui bat dans tous les siècles à la fois. Marc Alyn N Y PARUTION TRIMESTRIELLE L o A janvier 2011 — N 1 C R A M Marc Alyn — inédits — entretien 1 el Leuwers — Jacques Lovichi — Bernard Mazo O André Ughetto — Dani N Sylvestre Clancier — Emmanuel Hiriart — Pierre Brunel — Partage des voix 1 1 Pierre Dhainaut — Jean-Pierre Cramoisan — Cristophe Munier 0 ci — Isabelle Baladine Howald — Alain Fabre-Catalan 2 Téric Bouceb Jean Orizet — Bernard Mazo — Benito Pelegrín Voix d’ailleurs Giorgio Cittadini Mise en scène Notes de lectures ISBN : 978-2-919638-00-0 Prix public 9 782919 638000 : 16 € PHŒNIX No 1 MARC ALYN 1980 : dixième anniversaire de la revue SUD dans le jardin de la librairie La Touriale à Marseille (de gauche à droite : Yves Broussard, André Ughetto, Jacques Lovichi, Christiane Baroche, Jean-Max Tixier, Pierre Caminade, Benito Pelegrín, Frédéric Jacques Temple, Jacques Lepage, Claude Pocheron, Léon-Gabriel Gros, Jean Puech) LÉON-GABRIEL GROS Il se fit un grand tumulte dans la nuit Lorsque parut le messager. -

CÔTÉ MÉJANES Le Magazine Janvier & Février 2021 INFORMATIONS DE DERNIÈRE MINUTE FERMETURE À 17 H

CÔTÉ MÉJANES LE MAGAZINE JANVIER & FÉVRIER 2021 INFORMATIONS DE DERNIÈRE MINUTE FERMETURE À 17 H L’ amélioration espérée de la situation sanitaire n’est malheureusement pas au rendez-vous. Les dernières annonces gouvernementales nous conduisent à : ►fermer les bibliothèques à 17h à compter du mardi 12 janvier en raison du couvre-feu à 18h ►reporter à une date ultérieure l’exposition Germain Nouveau et les événement qui l’accompagnent ►remplacer les animations annoncées pour le mois de janvier dans le Côté Méjanes par les formes dématérialisées que nous avions préparées en « Plans B » (voir mode d’emploi en p. 3) EXPOSITION GERMAIN NOUVEAU Suite aux annonces du gouvernement le 7 janvier reportant la réouverture des expositions, nous devons décaler de quelques semaines l'ouverture de Germain Nouveau, l'ami de Verlaine et de Rimbaud (p. 12-15), ainsi que la programmation prévue dans ce cadre (Les Rendez-vous du patrimoine et des archives, p. 30-31). Nous vous tiendrons au courant et espérons pouvoir vous accueillir très prochainement pour cette exposition-événement ! LE ÉDITO SOMMAIRE l est des traditions qui participent du vivre ensemble, qui donnent à chacun et chacune DossIER (IM)PERMANENCE LES RENDEZ-VOUS DU savOIR PLAN B d’entre nous l’occasion d’espérer, d’imaginer et de se projeter. Se souhaiter une belle et • AUREL p. 4 • Les locaux qui font l'actu p. 29 MODE d’EMPLOI heureuse année en fait bien évidemment partie, peut-être encore davantage aujourd’hui, • FRANÇOIS BON p. 6 • Science pop' p. 29 La mise en œuvre des actions culturelles à l’heure où ces lignes sont rédigées, alors que s’achève une année 2020 qui fut pour tous LA GAZETTE DU MARQUIS LES RENDEZ-VOUS DU paTRIMOINE proposées dans ce numéro du Côté et toutes une année particulière, difficile, faite d’incertitude et de lendemains inconnus. -

Crossed Drawings (Rimbaud, Verlaine and Some Others) Author(S): Alain Buisine and Madeleine Dobie Reviewed Work(S): Source: Yale French Studies, No

Crossed Drawings (Rimbaud, Verlaine and Some Others) Author(s): Alain Buisine and Madeleine Dobie Reviewed work(s): Source: Yale French Studies, No. 84, Boundaries: Writing & Drawing (1994), pp. 95-117 Published by: Yale University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2930182 . Accessed: 19/07/2012 21:00 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Yale University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Yale French Studies. http://www.jstor.org ALAIN BUISINE Crossed Drawings*(Rimbaud, Verlaineand Some Others) Un jourpeut-6tre il disparaitramiraculeusement -D6lires I, Une Saison en Enferl He runs,he runs,the ferret,and it reallyisn't easy to catch him, to seize him as he passes by.But where exactlyhas he got to in this year 1876, ArthurRimbaud, the eternal absconder, the indefatigablevagabond? What has become of him? What is he doing? What has happened to him? How is he and how does he live? Is he still on the road, or has he set himself up provisionally,like some merchant or other,before re- turning,once more, to his distant wanderings?In France, his friends, with Paul Verlaine at the fore,speculate about his wild peregrinations and make fun of his misadventures,affabulating his activities and his discourse: Oh la la, j'ai rienfait de ch'mind'puis mon dergnier Copp6e ! I1est vraiqu'j'en suis chauv' commeun pagnier Perc6,qu'j'sens queut' chos' dans 1'gosierqui m'ratisse Qu'j'ai dansle dos comm'des avantgouits d'un rhumatisse, Et que j'm'emmerd'plusseuq' jamais.