1 the Value of Dihydrogen Monoxide to a Jumping Mouse: Habitat Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural History

NATURAL HISTORY By Kate Warren and Ian MacQuarrie nimals have a variety of gaits, with woods. They are very similar in size and very sensibly, in hibernation. A the pattern employed depending colour: brown backs, yellow sides shad- Aside from the tail tips, what are the upon habitat and circumstance. More- ing to white underneath. The easiest way main differences between the two spe- over, since much knowledge of the life to tell them from the runners is by their cies? Evolution theory suggests that and times of a species comes from inter- tails, which are longer than their bodies. there must be some dissimilarities, or preting tracks, some attention to the It is safe to assume that any mouse with else one would compete strongly against, dancing feet that make them is useful such a long tail is a jumping mouse. and perhaps eliminate, the other. There and often necessary. Basic biology, then, And how do you tell the jumping mice are, of course, differences in preferred is not just counting teeth; it is looking at apart? Again, the tail distinguishes them: habitat between woodland and meadow toes, and how these are picked up and the woodland jumping mouse has a white- jumpers, but they also differ in social put down. tipped tail, the meadow jumping mouse customs, behaviour. Both species are For instance, there are six species of does not. Such minor differences may b e somewhat nomadic, but the grassland small rodents on Prince Edward Island lost on your cat, but they are mighty jumper is usually found alone, while the that can generally be called "mice." handy for naturalists. -

5-Year Review Short Form Summary

5-Year Review Short Form Summary Species Reviewed: Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei) FR Notice Announcing Initiation of This Review: March 31, 2004. 90-Day Finding for a Petition to Delist the Preble’s Meadow Jumping Mouse in Colorado and Wyoming and Initiation of a 5-Year Review (69 FR 16944-16946). Lead Region/Field Office: Region 6, Seth Willey, Recovery Coordinator, 303-236-4257. Colorado Field Office, Susan Linner, Field Supervisor, 303-236-4773. Name of Reviewer: Peter Plage, Colorado Field Office, 303-236-4750. Cooperating Field Office: Wyoming Field Office, Brian Kelly, Field Supervisor, 307-772-2374. Current Classification: Threatened rangewide. Current Recovery Priority Number: 9c. This recovery priority number is indicative of a subspecies facing a moderate degree of threat, a high recovery potential, and whose recovery may be in conflict with construction or other development projects or other forms of economic activity. Methodology used to complete the review: The 5-year review for the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Preble’s) was accomplished through the petition and rulemaking process. On December 23, 2003, we received two nearly identical petitions from the State of Wyoming’s Office of the Governor and from Coloradans for Water Conservation and Development, seeking to remove the Preble’s from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Both petitions were similar and maintained that the Preble’s should be delisted based on the taxonomic revision, and based on new distribution, abundance, and trends data that suggested the Preble’s was no longer threatened. On March 31, 2004, we published a notice announcing a 90-day finding that the petitions presented substantial information indicating that the petitioned action may be warranted and initiated a 5-year review (69 FR 16944-16946). -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

BEFORE the SECRETARY of the INTERIOR Petition to List the Preble's Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus Hudsonius Preblei) As a Distinc

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR Petition to List the Preble’s Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei) as a Distinct Population Segment under the Endangered Species Act November 9, 2017 Petitioners: Center for Biological Diversity Rocky Mountain Wild Acknowledgment: Conservation Intern Shane O’Neal substantially contributed to drafting of this petition. November 9, 2017 Mr. Ryan Zinke CC: Ms. Noreen Walsh Secretary of the Interior Mountain-Prairie Regional Director Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 18th and C Street, N.W. 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 650 Washington, D.C. 20240 Lakewood, CO 80228 [email protected] Dear Mr. Zinke, Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. §424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity and Rocky Mountain Wild hereby formally petitions the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS”, “the Service”) to list the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei) as a distinct population segment. Although the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse is already currently listed as a subspecies, this petition is necessary because of a petition seeking to de-list the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (“jumping mouse”, “Preble’s”), filed by the Pacific Legal Foundation on behalf of their clients (PLF 2017), arguing that the jumping mouse no longer qualifies as a subspecies. Should FWS find this petition warrants further consideration (e.g. a positive 90-day finding), we are submitting this petition to ensure that the agency simultaneously considers listing the Preble’s as a distinct population segment of the meadow jumping mouse. -

Species Status Assessment Report New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus Hudsonius Luteus)

Species Status Assessment Report New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) (photo courtesy of J. Frey) Prepared by the Listing Review Team U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico May 27, 2014 New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse SSA May 27, 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment reports the results of the comprehensive status review for the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) (jumping mouse) and provides a thorough account of the species’ overall viability and, conversely, extinction risk. The jumping mouse is a small mammal whose historical distribution likely included riparian areas and wetlands along streams in the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan Mountains from southern Colorado to central New Mexico, including the Jemez and Sacramento Mountains and the Rio Grande Valley from Española to Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge, and into parts of the White Mountains in eastern Arizona. In conducting our status assessment we first considered what the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse needs to ensure viability. We generally define viability as the ability of the species to persist over the long-term and, conversely, to avoid extinction. We next evaluated whether the identified needs of the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse are currently available and the repercussions to the subspecies when provision of those needs are missing or diminished. We then consider the factors that are causing the species to lack what it needs, including historical, current, and future factors. Finally, considering the information reviewed, we evaluate the current status and future viability of the species in terms of resiliency, redundancy, and representation. -

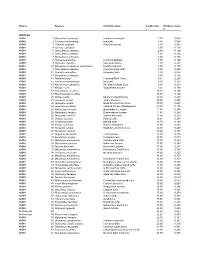

PDF File Containing Table of Lengths and Thicknesses of Turtle Shells And

Source Species Common name length (cm) thickness (cm) L t TURTLES AMNH 1 Sternotherus odoratus common musk turtle 2.30 0.089 AMNH 2 Clemmys muhlenbergi bug turtle 3.80 0.069 AMNH 3 Chersina angulata Angulate tortoise 3.90 0.050 AMNH 4 Testudo carbonera 6.97 0.130 AMNH 5 Sternotherus oderatus 6.99 0.160 AMNH 6 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 7 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 8 Homopus areolatus Common padloper 7.95 0.100 AMNH 9 Homopus signatus Speckled tortoise 7.98 0.231 AMNH 10 Kinosternon subrabum steinochneri Florida mud turtle 8.90 0.178 AMNH 11 Sternotherus oderatus Common musk turtle 8.98 0.290 AMNH 12 Chelydra serpentina Snapping turtle 8.98 0.076 AMNH 13 Sternotherus oderatus 9.00 0.168 AMNH 14 Hardella thurgi Crowned River Turtle 9.04 0.263 AMNH 15 Clemmys muhlenbergii Bog turtle 9.09 0.231 AMNH 16 Kinosternon subrubrum The Eastern Mud Turtle 9.10 0.253 AMNH 17 Kinixys crosa hinged-back tortoise 9.34 0.160 AMNH 18 Peamobates oculifers 10.17 0.140 AMNH 19 Peammobates oculifera 10.27 0.140 AMNH 20 Kinixys spekii Speke's hinged tortoise 10.30 0.201 AMNH 21 Terrapene ornata ornate box turtle 10.30 0.406 AMNH 22 Terrapene ornata North American box turtle 10.76 0.257 AMNH 23 Geochelone radiata radiated tortoise (Madagascar) 10.80 0.155 AMNH 24 Malaclemys terrapin diamondback terrapin 11.40 0.295 AMNH 25 Malaclemys terrapin Diamondback terrapin 11.58 0.264 AMNH 26 Terrapene carolina eastern box turtle 11.80 0.259 AMNH 27 Chrysemys picta Painted turtle 12.21 0.267 AMNH 28 Chrysemys picta painted turtle 12.70 0.168 AMNH 29 -

Zapus Hudsonius Luteus) Jennifer K

Variation in phenology of hibernation and reproduction in the endangered New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) Jennifer K. Frey Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Ecology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, United States of America Frey Biological Research, Radium Springs, NM, United States of America ABSTRACT Hibernation is a key life history feature that can impact many other crucial aspects of a species’ biology, such as its survival and reproduction. I examined the timing of hibernation and reproduction in the federally endangered New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus), which occurs across a broad range of latitudes and elevations in the American Southwest. Data from museum specimens and field studies supported predictions for later emergence and shorter active intervals in montane populations relative to lower elevation valley populations. A low-elevation population located at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge (BANWR) in the Rio Grande valley was most similar to other subspecies of Z. hudsonius: the first emergence date was in mid-May and there was an active interval of 162 days. In montane populations of Z. h. luteus, the date of first emergence was delayed until mid-June and the active interval was reduced to ca 124–135 days, similar to some populations of the western jumping mouse (Z. princeps). Last date of immergence into hibernation occurred at about the same time in all populations (mid to late October). In montane populations pregnant females are known from July to late August and evidence suggests that they have a single litter per year. At BANWR two peaks in reproduction were expected based Submitted 6 May 2015 on similarity of active season to Z. -

Wildlife Regulation

Province of Alberta WILDLIFE ACT WILDLIFE REGULATION Alberta Regulation 143/1997 With amendments up to and including Alberta Regulation 148/2013 Office Consolidation © Published by Alberta Queen’s Printer Alberta Queen’s Printer 5th Floor, Park Plaza 10611 - 98 Avenue Edmonton, AB T5K 2P7 Phone: 780-427-4952 Fax: 780-452-0668 E-mail: [email protected] Shop on-line at www.qp.alberta.ca Copyright and Permission Statement Alberta Queen's Printer holds copyright on behalf of the Government of Alberta in right of Her Majesty the Queen for all Government of Alberta legislation. Alberta Queen's Printer permits any person to reproduce Alberta’s statutes and regulations without seeking permission and without charge, provided due diligence is exercised to ensure the accuracy of the materials produced, and Crown copyright is acknowledged in the following format: © Alberta Queen's Printer, 20__.* *The year of first publication of the legal materials is to be completed. Note All persons making use of this consolidation are reminded that it has no legislative sanction, that amendments have been embodied for convenience of reference only. The official Statutes and Regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpreting and applying the law. (Consolidated up to 148/2013) ALBERTA REGULATION 143/97 Wildlife Act WILDLIFE REGULATION Table of Contents Interpretation and Application 1 Establishment of certain provisions by Lieutenant Governor in Council 2 Establishment of remainder by Minister 3 Interpretation 4 Interpretation for purposes of the Act 5 Exemptions and exclusions from Act and Regulation 6 Prevalence of Schedule 1 7 Application to endangered animals Part 1 Administration 8 Terms and conditions of approvals, etc. -

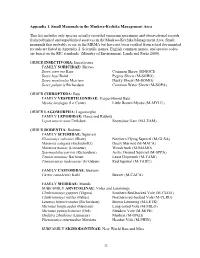

Appendices for Small Mammal Report

Appendix 1. Small Mammals in the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area This list includes only species actually recorded (museum specimens and observational records from published and unpublished sources) in the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area. Small mammals that probably occur in the MKMA but have not been verified from actual documented records are listed in Appendix 2. Scientific names, English common names, and species codes are based on the RIC standards (Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks 2000). ORDER INSECTIVORA: Insectivores FAMILY SORICIDAE: Shrews Sorex cinereus Kerr Common Shrew (M-SOCI) Sorex hoyi Baird Pygmy Shrew (M-SOHO) Sorex monticolus Merriam Dusky Shrew (M-SOMO) Sorex palustris Richardson Common Water Shrew (M-SOPA) ORDER CHIROPTERA: Bats FAMILY VESPERTILIONIDAE: Vespertilionid Bats Myotis lucifugus (Le Conte) Little Brown Myotis (M-MYLU) ORDER LAGOMORPHA: Lagomorphs FAMILY LEPORIDAE: Hares and Rabbits Lepus americanus Erxleben Snowshoe Hare (M-LEAM) ORDER RODENTIA: Rodents FAMILY SCIURIDAE: Squirrels Glaucomys sabrinus (Shaw) Northern Flying Squirrel (M-GLSA) Marmota caligata (Eschscholtz) Hoary Marmot (M-MACA) Marmota monax (Linnaeus) Woodchuck (M-MAMO) Spermophilus parryii (Richardson) Arctic Ground Squirrel (M-SPPA) Tamias minimus Bachman Least Chipmunk (M-TAMI) Tamiasciurus hudsonicus (Erxleben) Red Squirrel (M-TAHU) FAMILY CASTORIDAE: Beavers Castor canadensis Kuhl Beaver (M-CACA) FAMILY MURIDAE: Murids SUBFAMILY ARVICOLINAE: Voles and Lemmings Clethrionomys gapperi (Vigors) Southern Red-backed Vole (M-CLGA) Clethrionomys -

New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus Hudsonius Luteus)

New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service New Mexico Ecological Services Field Office Albuquerque, New Mexico January 30, 2020 1 5-YEAR REVIEW New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Listing History Species: New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) Date listed: June 10, 2014 Federal Register citations: • June 10, 2014. Determination of Endangered Status for the New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse Throughout Its Range (79 FR 33119) • March 16, 2016. Designation of Critical Habitat for the New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse; Final Rule ( 81 FR 14263) Classification: Endangered 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review: In accordance with section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act), the purpose of a 5-year review is to assess each threatened species and endangered species to determine whether its status has changed and it should be classified differently or removed from the Lists of Threatened and Endangered Wildlife and Plants. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) recently evaluated the biological status of the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse to update the original 2014 Species Status Assessment (SSA) report (Service 2014). The original SSA report supported the listing of the species as endangered in 2014 and the designation of critical habitat in 2016 within eight separate geographical management areas (GMAs). The updated SSA report (Service 2020) contains the scientific basis that the Service is using to inform this 5-year review, guiding future research projects that will answer key questions about the life history and ecology of the species, and supporting further recovery planning and implementation. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Diets and Foraging Behavior of Northern Spotted Owls in Oregon

The Journal of Raptor Research Volume 38 Number3 September2004 *.-. d--- , - \\Ci . / * - -- ",, Published by , . i r, ' .,.. :J' The Raptor Research Foundation, Inc. ,+-, ,+-, .$"<; , , . , , 3% I -1 * * ,, THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. (FOUNDED1966) http:/biology. boisestate.edu/raptor/ OFFICERS PRESIDENT: BwA. MILLSAP SECRETARY:JUDITH HENCKEL VICEPRESIDENT: DAVIDM. BIRD TREASURER: JIMFITZPATRICK BOARD OF DIRECTORS NORTH AMERICAN DIRECTOR #1: INTERNATIONAL DIRECTOR #3: JEFFSMITH STEVEREDPATH NORTH AMERICAN DIRECTOR #2: DIRECTOR AT LARGE #1: JEMIMA PARRY~ONES GARYSANTOLO DIRECTOR AT LARGE #2: EDWARDOINIGO-ELLAS NORTH AMERICAN DIRECTOR #3: DIRECTOR AT LARGE #3: MICHAELW. COLLOW TEDSWEM DIRECTOR AT LARGE #4: CAROLMcIm INTERNATIONAL DIRECTOR #1: DIRECTOR AT LARGE #5: JOHNA. SMALLWOOD BEATRIZARROYO DIRECTOR AT LARGE #6: DANIELE. VARLAND INTERNATIONAL DIRECTOR #2: RUTHTINGAY .................... EDITORIAL STAFF EDITOR: JAMESC. BEDNARZ,Department of Biological Sciences, P.O. Box 599, Arkansas State University, State University, AR 72467 U.S.A. ASSOCIATE EDITORS JAMES R. BELTHOFF JUANJOSENEGRO CLINTW. BOAL MARco RESTANI CHERYLR. DIXSTRA FABRIZIOSERGIO MICHAELI. GOLDSTEIN IAN G. WARKENTIN JOAN L. MORRISON JAMESW. WATSON BOOK REVIEW EDITOR: JEFFREYS. IMARKS, Montana Cooperative Research Unit, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812 U.S.A. SPANISH EDITOR: CisAR h4k~mzREYES, Instituto Humboldt, Colombia, AA. 094766, Bogoti 8, Colombia EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS: JENNIFER L. NORRIS,JOAN CLARK The Journal of Ruptor Research is distributed quarterly to all current members. Original manuscripts dealing with the biology and conservation of diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey are welcomed from throughout the world, but must be written in English. Submissions can be in the form of research articles, short communications, letters to the editor, and book reviews. Contributors should submit a typewritten original and three copies to the Editor.