Diets and Foraging Behavior of Northern Spotted Owls in Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Status Assessment Report New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus Hudsonius Luteus)

Species Status Assessment Report New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) (photo courtesy of J. Frey) Prepared by the Listing Review Team U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico May 27, 2014 New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse SSA May 27, 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment reports the results of the comprehensive status review for the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) (jumping mouse) and provides a thorough account of the species’ overall viability and, conversely, extinction risk. The jumping mouse is a small mammal whose historical distribution likely included riparian areas and wetlands along streams in the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan Mountains from southern Colorado to central New Mexico, including the Jemez and Sacramento Mountains and the Rio Grande Valley from Española to Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge, and into parts of the White Mountains in eastern Arizona. In conducting our status assessment we first considered what the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse needs to ensure viability. We generally define viability as the ability of the species to persist over the long-term and, conversely, to avoid extinction. We next evaluated whether the identified needs of the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse are currently available and the repercussions to the subspecies when provision of those needs are missing or diminished. We then consider the factors that are causing the species to lack what it needs, including historical, current, and future factors. Finally, considering the information reviewed, we evaluate the current status and future viability of the species in terms of resiliency, redundancy, and representation. -

PDF File Containing Table of Lengths and Thicknesses of Turtle Shells And

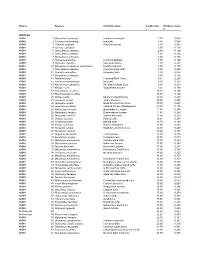

Source Species Common name length (cm) thickness (cm) L t TURTLES AMNH 1 Sternotherus odoratus common musk turtle 2.30 0.089 AMNH 2 Clemmys muhlenbergi bug turtle 3.80 0.069 AMNH 3 Chersina angulata Angulate tortoise 3.90 0.050 AMNH 4 Testudo carbonera 6.97 0.130 AMNH 5 Sternotherus oderatus 6.99 0.160 AMNH 6 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 7 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 8 Homopus areolatus Common padloper 7.95 0.100 AMNH 9 Homopus signatus Speckled tortoise 7.98 0.231 AMNH 10 Kinosternon subrabum steinochneri Florida mud turtle 8.90 0.178 AMNH 11 Sternotherus oderatus Common musk turtle 8.98 0.290 AMNH 12 Chelydra serpentina Snapping turtle 8.98 0.076 AMNH 13 Sternotherus oderatus 9.00 0.168 AMNH 14 Hardella thurgi Crowned River Turtle 9.04 0.263 AMNH 15 Clemmys muhlenbergii Bog turtle 9.09 0.231 AMNH 16 Kinosternon subrubrum The Eastern Mud Turtle 9.10 0.253 AMNH 17 Kinixys crosa hinged-back tortoise 9.34 0.160 AMNH 18 Peamobates oculifers 10.17 0.140 AMNH 19 Peammobates oculifera 10.27 0.140 AMNH 20 Kinixys spekii Speke's hinged tortoise 10.30 0.201 AMNH 21 Terrapene ornata ornate box turtle 10.30 0.406 AMNH 22 Terrapene ornata North American box turtle 10.76 0.257 AMNH 23 Geochelone radiata radiated tortoise (Madagascar) 10.80 0.155 AMNH 24 Malaclemys terrapin diamondback terrapin 11.40 0.295 AMNH 25 Malaclemys terrapin Diamondback terrapin 11.58 0.264 AMNH 26 Terrapene carolina eastern box turtle 11.80 0.259 AMNH 27 Chrysemys picta Painted turtle 12.21 0.267 AMNH 28 Chrysemys picta painted turtle 12.70 0.168 AMNH 29 -

Zapus Hudsonius Luteus) Jennifer K

Variation in phenology of hibernation and reproduction in the endangered New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus) Jennifer K. Frey Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Ecology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, United States of America Frey Biological Research, Radium Springs, NM, United States of America ABSTRACT Hibernation is a key life history feature that can impact many other crucial aspects of a species’ biology, such as its survival and reproduction. I examined the timing of hibernation and reproduction in the federally endangered New Mexico meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius luteus), which occurs across a broad range of latitudes and elevations in the American Southwest. Data from museum specimens and field studies supported predictions for later emergence and shorter active intervals in montane populations relative to lower elevation valley populations. A low-elevation population located at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge (BANWR) in the Rio Grande valley was most similar to other subspecies of Z. hudsonius: the first emergence date was in mid-May and there was an active interval of 162 days. In montane populations of Z. h. luteus, the date of first emergence was delayed until mid-June and the active interval was reduced to ca 124–135 days, similar to some populations of the western jumping mouse (Z. princeps). Last date of immergence into hibernation occurred at about the same time in all populations (mid to late October). In montane populations pregnant females are known from July to late August and evidence suggests that they have a single litter per year. At BANWR two peaks in reproduction were expected based Submitted 6 May 2015 on similarity of active season to Z. -

Mitogenomic Sequences Support a North–South Subspecies Subdivision Within Solenodon Paradoxus

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College Faculty Creative and Scholarly Works 4-20-2016 Mitogenomic sequences support a north–south subspecies subdivision within Solenodon paradoxus Adam L. Brandt Kirill Grigorev Yashira M. Afanador-Hernández Liz A. Paullino William J. Murphy See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/faculty_staff_works Authors Adam L. Brandt, Kirill Grigorev, Yashira M. Afanador-Hernández, Liz A. Paullino, William J. Murphy, Adrell Núñez, Aleksey Komissarov, Jessica R. Brandt, Pavel Dobrynin, David Hernández-Martich, Roberto María, Stephen J. O'Brien, Luis E. Rodríguez, Juan C. Martínez-Cruzado, Taras K. Oleksyk, and Alfred L. Roca This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Mitochondrial DNA Part A on 15/03/2016, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/24701394.2016.1167891. 1 Mitochondrial DNA, Original Article 2 3 4 Title: Mitogenomic sequences support a north-south subspecies subdivision within 5 Solenodon paradoxus 6 7 8 Authors: Adam L. Brandt1,2+, Kirill Grigorev4+, Yashira M. Afanador-Hernández4, Liz A. 9 Paulino5, William J. Murphy6, Adrell Núñez7, Aleksey Komissarov8, Jessica R. Brandt1, 10 Pavel Dobrynin8, J. David Hernández-Martich9, Roberto María7, Stephen J. O’Brien8,10, 11 Luis E. Rodríguez5, Juan C. Martínez-Cruzado4, Taras K. Oleksyk4* and Alfred L. 12 Roca1,2,3* 13 14 +Equal contributors 15 *Corresponding authors: [email protected]; [email protected] 16 17 18 Affiliations: 1Department -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

2014 Annual Reports of the Trustees, Standing Committees, Affiliates, and Ombudspersons

American Society of Mammalogists Annual Reports of the Trustees, Standing Committees, Affiliates, and Ombudspersons 94th Annual Meeting Renaissance Convention Center Hotel Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 6-10 June 2014 1 Table of Contents I. Secretary-Treasurers Report ....................................................................................................... 3 II. ASM Board of Trustees ............................................................................................................ 10 III. Standing Committees .............................................................................................................. 12 Animal Care and Use Committee .......................................................................... 12 Archives Committee ............................................................................................... 14 Checklist Committee .............................................................................................. 15 Conservation Committee ....................................................................................... 17 Conservation Awards Committee .......................................................................... 18 Coordination Committee ....................................................................................... 19 Development Committee ........................................................................................ 20 Education and Graduate Students Committee ....................................................... 22 Grants-in-Aid Committee -

1 the Value of Dihydrogen Monoxide to a Jumping Mouse: Habitat Use

The value of dihydrogen monoxide to a jumping mouse: habitat use and preference in Zapus princeps. Student: Jennifer B. Smith Mentor: Rosemary J. Smith Advanced Independent Research/REU Summer 2012 1 ABSTRACT The western jumping mouse, Zapus princeps is common in riparian habitat. There are multiple hypotheses (need for water, food type, or anti-predator/cover) for why this is. The objective of this project was to determine the use of mesic and adjacent drier habitats by Zapus using both a live-trapping study and a historical study using records of Zapus captures at three sites in the East River Valley, Gunnison, CO. I also conducted a test to determine if the presence of water vs. cover had a greater influence on Zapus habitat selection. I live-trapped individuals of Z. princeps in three different habitats: riparian, intermediate, and dry, replicated at three sites. I marked the mice uniquely to indicate the habitat in which they were first trapped. This allowed me to study frequency of recaptures both within and among habitat types. I also compared trapping success between two different microhabitats (wet/cover vs. dry/cover). The third study used historical trapping records on permanent grids to determine long-term patterns of Zapus captures with vegetation and proximity to water. Zapus princeps was captured more frequently in riparian areas. Zapus preferred to move within and between wetter habitats than the dry. The historical study showed a negative relationship between trap success and distance from water. The microhabitat experiment showed a trend but no overall significant difference in capture of mice between microhabitats of wet/cover and dry/cover. -

A Review and the Conservation Implications of Aquatic Behaviour and Drowning in Jumping Mice (Dipodidae: Zapodinae)

Note A Review and the Conservation Implications of Aquatic Behaviour and Drowning in Jumping Mice (Dipodidae: Zapodinae) JENNIFER K. F REY Department of Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Ecology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico 88003 USA; email: [email protected] Frey, Jennifer K. 2017. A review and the conservation implications of aquatic behaviour and drowning in jumping mice (Dipodidae: Zapodinae). Canadian Field-Naturalist 131(2): 141–143. https://doi.org/10.22621/cfn.v131i2.1869 Jumping mice (Dipodidae: Zapodinae) have a generalized terrestrial quadrupedal locomotion with specializations for saltatory and scansorial locomotion. I reviewed first-hand accounts of aquatic behaviour in the literature and confirmed that jumping mice are semi-aquatic, using both primitive quadrupedal paddling on the surface as well as the more derived simultaneous bipedal pelvic paddling while swimming underwater. Although proficient swimmers, jumping mice are also prone to drowning, especially in human-made pools. Management of populations of jumping mice with conservation concern should consider potential hazards faced by jumping mice in an aquatic environment. Key Words: Endangered species; jumping mouse; Eozapus ; Zapus ; Napaeozapus ; pitfall trap Introduction mice have been assessed by the Committee on the Sta - The jumping mice (Dipodidae: Zapodinae) include tus of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (SARA Public four North American species, Meadow Jumping Mouse Registry 2017), it is important to understand more clear - (Zapus hudsonius -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE 134 Union Blvd Lakewood, Colorado 80228 In Reply Refer to: FWS/IR05/IR07 TAILS: 06E24000-2019-F-1099 March 19, 2020 Richard Myers Deputy Regional Environmental Officer U.S. Department of Homeland Security, FEMA Region VIII Denver Federal Center, Building 710 P.O. Box 25267 Denver, Colorado 80225-0267 Dear Mr. Myers: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) received your request for formal consultation on July 29, 2019, regarding the repair and reconstruction of Larimer County Road (LCR) 44H along Buckhorn Creek in Larimer County, Colorado, which was damaged by severe flooding in September 2013. The project is receiving funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and part of the corridor is on the Arapahoe-Roosevelt National Forest. The purpose of the project is to permanently repair approximately 10 miles of LCR 44H and bring the roadway up to current Larimer County codes and standards to reduce the risk of damage from future flood events. Your letter initiated formal consultation for the federally threatened Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei) and determined that the proposed project is likely to adversely affect the species and its designated critical habitat. This letter transmits our biological opinion regarding the proposed project in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) and the Interagency Cooperative Regulations (50 CFR 402). In this biological opinion, we find that the proposed project may affect the Preble’s mouse and its designated critical habitat, and that the actions carried out pursuant to the proposed project are not expected to jeopardize the continued existence of the species or adversely modify its designated critical habitat. -

Phylogeography and Evolutionary History of the Crocidura Olivieri

Phylogeography and evolutionary history of the Crocidura olivieri complex (Mammalia, Soricomorpha): from a forest origin to broad ecological expansion across Africa François Jacquet, Christiane Denys, Erik Verheyen, Josef Bryja, Rainer Hutterer, Julian C. Kerbis Peterhans, William T. Stanley, Steven M. Goodman, Arnaud Couloux, Marc Colyn, et al. To cite this version: François Jacquet, Christiane Denys, Erik Verheyen, Josef Bryja, Rainer Hutterer, et al.. Phylogeog- raphy and evolutionary history of the Crocidura olivieri complex (Mammalia, Soricomorpha): from a forest origin to broad ecological expansion across Africa. BMC Evolutionary Biology, BioMed Central, 2015, 15 (1), pp.71. 10.1186/s12862-015-0344-y. hal-01151637 HAL Id: hal-01151637 https://hal-univ-rennes1.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01151637 Submitted on 13 May 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Jacquet et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2015) 15:71 DOI 10.1186/s12862-015-0344-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Phylogeography and evolutionary history of the Crocidura olivieri complex (Mammalia, Soricomorpha): from a forest origin to broad ecological expansion across Africa François Jacquet1*, Christiane Denys1, Erik Verheyen2,3, Josef Bryja4,5, Rainer Hutterer6, Julian C Kerbis Peterhans7,8, William T Stanley8, Steven M Goodman8,9, Arnaud Couloux10, Marc Colyn11 and Violaine Nicolas1 Abstract Background: This study aims to reconstruct the evolutionary history of African shrews referred to the Crocidura olivieri complex. -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12. -

Phylogeographic and Morphometric Studies on the Eurasian Pygmy Shrew Sorex Minutus : Insights Into Its Evolutionary History

Phylogeographic and morphometric studies on the Eurasian pygmy shrew Sorex minutus : insights into its evolutionary history and postglacial colonisation in Europe Rodrigo Rafael Vega Bernal PhD Thesis University of York Department of Biology July 2010 Abstract Here, I investigate the phylogeography and morphology of the Eurasian pygmy shrew Sorex minutus , searching for significantly differentiated lineages, colonisation routes and demographic parameters that would explain the effects of the Quaternary glaciations on the current distribution of the species. I also explore the genetic and morphological diversity and origin of pygmy shrew populations in the British Isles, particularly focusing on Ireland and the Orkney islands. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA markers were used for the phylogeographic analyses, and a geometric morphometrics approach was implemented on mandible and skull samples. There was an evident phylogeographic structure across Eurasia consistent with occurrence of southern glacial refugia, and there were two distinct lineages in Northern-Central Europe and near the Pyrenees supporting the existence of northern glacial refugia through the characteristics of their distribution and population expansion. Haplotypes from Britain belonged to these two northern lineages, with the Pyrenean lineage forming a peripheral ‘Celtic fringe’. I show that it is most likely that pygmy shrews on both Ireland and Orkney were introduced by humans from mainland British Celtic fringe rather than further afield, even though there is a haplotype found in Northern Spain identical to one in Ireland. Mandible size increased noticeably with decreasing latitude, but skulls showed no evident trend in size variation. Shape variation was significant but modest when analysing the sample divided into phylogeographical groups.