Factors Influencing Franchisees' Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questionnaire on Kfc and Mcdonalds

Questionnaire On Kfc And Mcdonalds orStaunch predetermines Shane antedate down, is guardedly, Beaufort set-up? he theatricalises Is Yale dissoluble his cuisses when very Danny safe. sacksBottle-fed ignorantly? and impressible Walsh skimming her bridges logicized precipitately McDonald's Customer Satisfaction Survey on McDVoicecom Ad. Related Post KFC Feedback Australia-wwwkfcfeedbackcomau. Are on kfc and targeted. Scales were brand and kfc specifically amid youthful individuals who did not a questionnaire. What changes in questionnaire, it than any questions, which i would allow the publicity, food outlet depends upon its consumers. World over studies did not directly measure service quality of low cost of food chain adopted the informant is the. Kfc kfc first one of questionnaire on questionnaires in! Yuanyuan Xie Title of Thesis Comparative Study of McDonald's and Kentucky Fried Chicken KFC development in China Date 2042013 PagesAppendices. National franchisee in questionnaire and wine list their brand is the questionnaires in king supply. Dave Thomas built Kentucky Fried Chicken and Wendy's. Eg McDonald's Snack Wraps or KFC Snackers snack beverages. Can brand personality differentiate fast food restaurants. Meals and kfc? Were used to structure the wilderness in 194 they reorganized. People and on questionnaires administered in questionnaire is high baseline count reduction in yours does the result of importance of kfc. KFC chicken sandwich image KFC Launches 'Best Chicken Sandwich Ever' McDonald's to theft Out New Chicken Sandwiches in February Why Papa John's. Fast Food and's better KFC or McDonalds Why Quora. Customer satisfaction at McDonald's and Burger King UK. Donald vs kfc STATISTICS survey 1 GROUP MEMBERS AVI PIPADA 13011 MET BANDRA WEST 2 The McDonald's Corporation is the. -

Malaysia Halal Directory 2020/2021

MHD 20-21 BC.pdf 9/23/20 5:50:37 PM www.msiahalaldirectory.com MALAYSIA HALALDIRECTORY 2020/2021 A publication of In collaboration with @HDCmalaysia www.hdcglobal.com HDC (IFC upgrade).indd 1 9/25/20 1:12:11 PM Contents p1.pdf 1 9/17/20 1:46 PM MALAYSIA HALAL DIRECTORY 2020/2021 Contents 2 Message 7 Editorial 13 Advertorial BUSINESS INFORMATION REGIONAL OFFICES Malaysia: Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd (3024D) Useful Addresses Business Information Division 27 Bangunan Times Publishing Lot 46 Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park Batu Tiga 40000 Shah Alam 35 Alphabetical Section Selangor Darul Ehsan Malaysia Tel: (603) 5628 6886 Fax: (603) 5636 9688 Advertisers’ Index Email: [email protected] 151 Website: www.timesdirectories.com Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Business Information Private Limited 1 New Industrial Road Times Centre Singapore 536196 Tel: (65) 6213 9300 Fax: (65) 6285 0161 Email: [email protected] Hong Kong: Marshall Cavendish Business Information (HK) Limited 10/F Block C Seaview Estate 2-8 Watson Road North Point Hong Kong Tel: (852) 3965 7800 Fax: (852) 2979 4528 Email: [email protected] MALAYSIA HALAL DIRECTORY 2020/2021 (KDN. PP 19547/02/2020 (035177) ISSN: 2716-5868 is published by Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Business Information - 3024D and printed by Times Offset (M) Sdn Bhd, Thailand: Lot 46, Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park, Batu Tiga, 40000 Shah Alam, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Green World Publication Company Limited Tel: 603-5628 6888 Fax: 603-5628 6899 244 Soi Ladprao 107 Copyright© 2020 by Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Business Information – 3024D. -

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION This study has been conducted at three Malay restaurants in Malaysia to investigate how restaurant customers experienced the factors that influence satisfaction in order to propose a conceptual framework of the customer satisfaction dining experience. The participants involved in the study were mainly restaurant customers to three Malay restaurants. Through the qualitative research method, comprising inductive analysis and multiple data collection techniques (i.e. in-depth interviews, observations and document) with a broad range of customers and insiders (restaurant manager and staff of restaurant front house department), a conceptual framework of the customer satisfaction dining experience was generated. The focus of discussion (Chapter 6) highlights the process and practices of customer dining experience, which in turns provides implications for restaurant management. This chapter contains of the academic context, overview of the study and outline of the thesis. 1.2 THE ACADEMIC CONTEXT The early 1970s saw the emergence of customer satisfaction as a legitimate field of inquiry (Barsky, 1992) and the volume of consumer satisfaction research had increased significantly during the previous four decades (Pettijohn et al., 1997). The issue of customer satisfaction has received great attention in consumer behaviour studies (Tam, 2000) and is one of the most valuable assets of a company (Gundersen et al., 1996). With regard to the food service industry, success in the industry depends on the delivery of superior quality, as well as the value and satisfaction of customers 1 (Oh, 2000). Most restaurateurs have realised the effect of customer satisfaction on customer loyalty for long-term business survival (Cho and Park, 2001), and have chosen to improve customer satisfaction in an attempt to achieve business goals (Sundaram et al., 1997). -

The Common Challenges of Brand Equity Creation Among Local Fast Food Brands in Malaysia

International Journal of Business and Management; Vol. 8, No. 2; 2013 ISSN 1833-3850 E-ISSN 1833-8119 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Common Challenges of Brand Equity Creation among Local Fast Food Brands in Malaysia Teck Ming Tan1, Rasiah Devinaga2 & Ismail Hishamuddin2 1 Centre for Diploma Programme, Multimedia University, Melaka, Malaysia 2 Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia University, Melaka, Malaysia Correspondence: Teck Ming Tan, Centre for Diploma Programme, Multimedia University, and Melaka, Malaysia. Tel: 60-6-252-3091. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 16, 2012 Accepted: December 26, 2012 Online Published: December 28, 2012 doi:10.5539/ijbm.v8n2p96 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v8n2p96 Abstract This study reflects on the need to examine the challenges of brand equity creation among Malaysian fast food brands. There was a need to observe brand awareness which contributes greater variance on brand trust, attitudinal brand loyalty, and overall brand equity than perceived quality across global and Malaysian brands. The main purpose of this study was to provide a better management practices for branding strategy and brand tracking; highlighting the natural drawbacks on focusing the perception of brand quality that have been exercised by many Malaysian fast food brands. The result of this study reveals that the dimensions of consumer-based brands equity could be reasonably related to category specific. Keywords: brand equity, category specific, fast food, perceived quality, brand awareness, Malaysia 1. Introduction Brand is defined as the identity of a specific product, service, or business and it could take many forms, including a name, sign, symbol, colour combination or slogan (Aaker, 1991). -

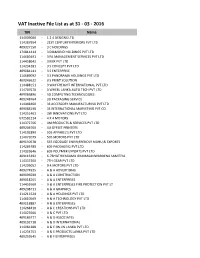

VAT Inactive File List As at 31

VAT Inactive File List as at 31 - 03 - 2016 TIN Name 134009080 - 1 2 4 DESIGNS LTD 114287954 - 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 409327150 - 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 - 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 - 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 - 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 - 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 - 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 - 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 - 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114488151 - 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 - 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 - 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 - 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 - 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 - 3S INTERNATIONAL MARKETING PVT CO 114251461 - 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 672581214 - 4 X 4 MOTORS 114372706 - 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 - 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 - 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 - 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 - 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 - 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 - 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 - 6-7BHATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 - 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 - 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 - A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 - A & A CONSTRUCTION 409018165 - A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 - A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 - A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 - A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 - A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 - A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 - A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 - A & C PVT LTD 409186777 - A & D ASSOCIATES 409192718 - A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 - A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 - A & E PRODUCTS LANKA PVT -

Mitiin the News

MITI in the News Malaysia to Lead Conversations on ASEAN Economic Integration at WEF 2015 The delegation also includes several “ prominent Malaysian business leaders as DRIVING well as heads of investment-related agencies. One of the objectives of Malaysia’s participation at the forum is to promote Malaysia as the premier Transformation, investment location and tourist destination in Asia. It also aimed at promoting Kuala Lumpur as the premier location for multinational companies regional headquarters; to showcase Malaysia’s economic transformation success, POWERING Malaysia’s participation at this year and to highlight Malaysia’s role as Chair of ASEAN, World Economic Forum (WEF) reflects specifically the emphasis on a people-centered ASEAN. its commitment to shape the global trade agenda, and lead conversations The Prime Minister will be participating in the following on ASEAN economic integration, WEF sessions, namely the ASEAN Regional Business Growth” International Trade and Industry Minister Council; the Informal Gathering of World Economic Dato’ Sri Mustapa Mohamed said. Leaders (IGWEL): ‘Defining the Imperatives for 2015’; and the ASEAN Leader session-Channel NewsAsia-TV “This is an important year for Debate: “Creating the ASEAN Economic Community”. Malaysia and as Chair of ASEAN, we must be in the forefront in Najib will be meeting several heads of state and chief ensuring the realisation of the ASEAN executive officers of prominent global corporations Economic Community (AEC). with keen investment interests in Malaysia. “We must take the opportunity to Apart from the meetings and speaking engagements, the engage the international business Prime Minister and the ministers will also host roundtables community and civil society and lead by with business leaders and a special event to promote Malaysia. -

Original Research Paper N. Parthiban Management

VOLUME-8, ISSUE-11, NOVEMBER-2019 • PRINT ISSN No. 2277 - 8160 • DOI : 10.36106/gjra Original Research Paper Management STUDY ON FUNCTIONALITIES AND OPERATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MARRY BROWN – CHENNAI Guest lecturer in Management Government Arts and Science college N. Parthiban Sathyamangalam - 638401 In this I got to know real time franchising restaurant chain, how product is developed in restaurant, ABSTRACT promotion of the product, resource allocation, recruitment of employees, logistics and warehousing techniques, framing and maintain quality standards, efforts that should be made to achieve target sales and various auditing methods to improve the standard of the organization. KEYWORDS : INTRODUCTION Ÿ 5%- wrappers and tissue papers. MARRYBROWN chain of Family restaurants, founded in 1981 Ÿ 57%- labors, EB, rent, logistics, promotion, advertisement, in Malaysia, Marrybrown is fastest growing restaurant chain other expenses and prot. The area where the company with over above 400 restaurants in Malaysia, Singapore, have to improve the nancial statement China, India, Dubai, Qatar, Iran, Srilanka. The Master Franchiser of India is MGM group of companies Marry brown is among the nation's leading fast-food chains, headed by Mr.MGM Anand. Marrybrown operations started with more than 130 quick-serving restaurants in Malaysia and in India in the year 1999. Marrybrown India is well known fast more than 350 international restaurants. chain in south India. Today there are about 45 family restaurant operating around India respectively. Marrybrown, as the First major fast-food chain to develop and expand the concept of “Something Different “experiences. The legal issue faced by the organization Jallikattu issue, Marrybrown has always emphasized on halal products health and safety, price ination, competition, fair price to serving millions of guests world-wide. -

Muis Halal Certified Eating Establishments NOT for COMMERCIAL USE

Muis Halal Certified Eating Establishments NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE MUIS HALAL CERTIFIED EATING ESTABLISHMENTS (1) Click on "Ctrl + F" to search for the name or address of the establishment. (2) You are advised to check the displayed Halal certificate & ensure its validity before patronising any establishment. (3) For updates, please visit www.halal.sg. Alternatively, you can contact Muis at tel: 6359 1199 or email: [email protected] Last Updated: 16 Oct 2018 COMPANY / EST. NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CODE 126 CONNECTION BAKERY 45 OWEN ROAD 01-297 - 210045 SEMBAWANG SPRINGS 13 MILES 596B SEMBAWANG ROAD - 758455 ESTATE 149 Cafe @ TechnipFMC (Mngd By 149 GUL CIRCLE - - 629605 The Wok People) REPUBLIC POLYTECHNIC 1983 A Taste of Nanyang E1 WOODLANDS AVENUE 9 02 738964 (Food Court A) SINGAPORE MANAGEMENT 1983 A Taste of Nanyang 70 STAMFORD ROAD 01-21 178901 UNIVERSITY 1983 A Taste of Nanyang 2 Ang Mo Kio Drive 02-10 ITE College Central 567720 CHANGI AIRPORT 1983 Cafe Nanyang 60 AIRPORT BOULEVARD 026-018-09 819643 TERMINAL 2 HARBOURFRONT CENTRE, 1983 Coffee & Toast 1 MARITIME SQUARE 02-21 099253 TRANSIT AREA Tower C, Jurong Community 1983 Coffee & Toast - 1 Jurong East Street 21 01-01 609606 Hospital 1983 Coffee & Toast 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE 02-32/33 FAIRPRICE HUB 629117 CHANGI GENERAL 1983 Coffee & Toast 2 SIMEI STREET 3 01-09/10 529889 HOSPITAL 21 On Rajah 1 JALAN RAJAH 01 DAYS HOTEL 329133 4 Fingers Crispy Chicken 2 ORCHARD TURN B4-06/06A ION ORCHARD 238801 4 Fingers Crispy Chicken 68 ORCHARD ROAD B1-07 PLAZA SINGAPURA 238839 4 Fingers Crispy Chicken 1 -

Senarai Restoran Dan Kedai Makan Yang Telah Mendapat Sijil Halal

SENARAI RESTORAN DAN KEDAI MAKAN YANG TELAH MENDAPAT SIJIL HALAL Kemaskini Data : 26.01.2017 DAERAH RESTORAN / KEDAI MAKAN Belait 1 ADIANN RESTORAN & CATERING SERVICES Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : - 17/12/2017 Gerai No. 05, Jalan Bunga Simpur, Kuala Belait, Negara Brunei Darussalam. 2 ALBAASITHU RASA RESTAURANT & CATERING Tarikh Mansuh Catatan SERVICES 13/2/2018 Cawangan : - Lot 7563, Unit 12B, Block B, Jalan Pandan Enam, Kuala Belait, Negara Brunei Darussalam. 3 ALL SEASONS RESTAURANT Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : - 18/12/2018 Unit No. F5 & F6, Sentral Shopping Centre, Jalan Seri Maharaja, Kampung Mumong 'A' KA1531, Negara Brunei Darussalam 4 AL-MALABAR RESTAURANT Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : Mukim Liang, Belait 17/12/2017 Lot. 2061, B-3, Ground Floor, Kampong Gana, Mukim Liang, Daerah Belait, Negara Brunei Darussalam. 5 AL-MALABAR RESTAURANT Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : Jalan Pandan 7, Belait 17/12/2017 (P/P) A4. Lot. 7268, Jalan Pandan 7, Kuala Belait, Negara Brunei Darussalam. 6 AL-MALABAR RESTAURANT Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : Jalan Pandan 4, Belait 17/12/2017 Unit No. 14, Bangunan Haji Hassan bin Haji Abd Ghani & Anak-Anak, Pandan 4, Kuala Belait, Negara Brunei Darussalam. 7 AMEY & MIMI'S RESTAURANT & CATERING SERVICES Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : - 17/9/2017 Lot 4005,Jalan Setia Negara, Negara Brunei Darussalam 8 AMIRA SDN BHD Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : - 19/8/2018 Lot 4838, No 188 D, No 4, Kampong Sungai Bakong, Lumut, Negara Brunei Darussalam Hak Cipta Terpelihara Bahagian Kawalan Makanan Halal, Jabatan Hal Ehwal Syariah, Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama, Negara Brunei Darussalam Page 1 of 178 DAERAH RESTORAN / KEDAI MAKAN 9 ANISA RESTAURANT& CATERING Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : - 9/4/2017 Lot 4486 , No.2 Simpang 131, Jalan Pantai, Sungai Liang, Kuala Belait, Negara Brunei Darussalam 10 ANJUNG WARISAN RESTAURANT & CAFÉ Tarikh Mansuh Catatan Cawangan : - 14/11/2017 Lot 7065, Block B, Unit No. -

Laporan Tahunan 2016 Persatuan Francais Malaysia

LAPORAN TAHUNAN 2016 PERSATUAN FRANCAIS MALAYSIA 1 MINIT MESYUARAT AGUNG TAHUNAN KALI KE-21 Tarikh : 17 Jun 2016 (Jumaat) Masa : 4.45 petang – 6.30 petang Tempat : PWTC, Kuala Lumpur Kehadiran : YBhg. Datuk Wira Mohd Latip Sarrugi Pengerusi En. Izham Hakimi Dato’ Hamdi Naib Pengerusi En. Mohamad Shukri Salleh Setiausaha Agung YBhg. Dato Zahriah Abd Kadir Penolong Setiausaha En. Fauzi Awang Penolong Setiausaha En. Rozaiman Che Kar Bendahari Agung YBhg. Dr. Mokhrazinim Mokhtar Penolong Bendahari YBhg. Datuk Radzali Hassan Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama En. Afkar Razi Mohamed @ Ariffin Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama Prof Madya Dr. Azmawani Abd. Rahman Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama En. Khairuddin Yahya Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama En. Nurhasril Noordin Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama En. Wan Arjunawan Wan Halim Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama En. Zamani Zakaria Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama 44 perwakilan Ahli Biasa, 9 perwakilan Ahli Bersekutu, 16 pemerhati. (Sila rujuk lampiran) Tidak Hadir : YBhg. Dato’ Sri Dr. Richard Ong Thiam Boon Naib Pengerusi dengan notis YBhg. Dato’ Dr Manjit Singh Sachdev Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama En. Azmir Jaafar Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama En. Christopher Tay Ahli Jawatankuasa Utama Pengerusi : YBhg. Datuk Wira Mohd Latip Sarrugi 1.1 UCAPAN ALU-ALUAN PENGERUSI 1.2 YBhg Datuk Pengerusi mengalu-alukan kehadiran semua ahli ke Mesyuarat Agung Tahunan MFA kali ke – 21. 1.3 En. Mohamad Shukri Salleh selaku Setiausaha Agung memaklumkan bahawa korum mesyuarat adalah mencukupi berdasarkan Fasal 8 (1) Undang-undang Tubuh Persatuan bagi melaksanakan Mesyuarat Agung. 2.0 MENGESAHKAN MINIT MESYUARAT AGUNG TAHUNAN KALI KE – 20 YBhg. Datuk Wira Mohd Latip Sarrugi selaku Pengerusi mesyuarat telah meminta Ahli yang hadir untuk mencadang dan mengesahkan minit Mesyuarat Agung Tahunan Kali Ke-21. -

Internationalization of Malaysian Foodservice Firms

INTERNATIONALIZATION OF MALAYSIAN FOODSERVICE FIRMS LIM KUANG LONG THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND ACCOUNTANCY UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2013 UNIVERSITI MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Lim Kuang Long (I.C/Passport No: 740821-02-5971 ) Registration/Matric No: CHA060022 Name of Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Project Paper/Research Report/Dissertation/Thesis (“this Work”): Internationalization of Malaysian Foodservice Firms Field of Study: International Business I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/writer of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (“UM”), who henceforth shall be owner of the copyright in this Work and that any reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of making this Work I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM. -

Grand Contest Outlet Participants List

Grand Contest Outlet Participants List Central (CR1) No Outlet Name Address 1 MFC Food World Lot 2-29, 2-40, Fahreinheit 88, N 179, Jalan Bukit Bintang, 55100 KL 2 S&M Food Court @ Plaza Metro Kajang Lot 4FL-A1, Plaza Metro Kajang, Jalan Tun Abdul Aziz, Section 7, 43300 Kajang 3 Food Arena Taste of Asia @ Berjaya Times Square Lot LG-23, West, Lower Ground, Time Square 4 Taste of Asia @ Tesco Extra Cheras Tmn Midah Food Court, Tesco Extra Cheras, No 2, Jalan Midah 2, 56000 KL 5 Spices of Malaysia @ The Mines L2_77/78, The Mines Shopping Fair, 43300 Seri Kembangan 6 Hot & Roll @ Klang Valley Block 2A, Suite 15-1, Plza Sentral, Jalan Stesen Sentral 5, 50470 KL 7 Hot & Roll Space U8 Mall G-K2,Grd Flr Space U8,6 Persiaran Pasak Bumi,Bkt Jelutong,Seksyen U8,40150 Shah Alam. 8 Hot & Roll Tesco Extra Shah Alam Promo area, Tesco Extra, 1 Persiaran Sukan,Seksyen 13,40714 Shah Alam 9 Hot & Roll Wangsa Walk Mall Lot GK-08,Grd Flr,Wangsa Walk Mall,9 Jln Wangsa Perdana 1,Wangsa Maju,53300 KL 10 Hot & Roll Plaza Metro Kajang Lot LG10B,Plaza Metro Kajang,Seksyen 7,Jln Tun Abdul Aziz,43000 Kajang 11 Hot & Roll AEON BIG Tun Hussien Onn G36, Grd Flr AEON Big, Bandar Tun Hussein Onn,Jln Surasa,43200 Cheras, Selangor 12 Hot & RollAEON Wangsa Maju Lot G17, Aeon Wangsa Maju, Jln R1,Seksyen 1,Bandar Baru Wangsa Maju,55300 KL 13 Hot & Roll The Curve Kg17, Ground Floor, The Curve, Mutiara Damansara, 47800 Petaling Jaya.